I have decided to take another look at my book idea that became the kernel and “original draft” for my later volume, 100 Biblical Arguments Against Sola Scriptura: published by Catholic Answers in 2012. The initial title in 2009 was 501 Biblical Arguments Against Sola Scriptura: Is the Bible the Only Infallible Authority? I undertook that project after an anti-Catholic Protestant remarkably and ridiculously claimed there were “no” arguments whatever against sola Scriptura in the Bible. So I produced 501.

Now, mind you, many of them were very short (a sentence or two). The book was in the format and style of Blaise Pascal’s Pensées (“Thoughts”): a classic apologetics work published in 1670. Wikipedia describes it as:

. . . fragments that Pascal had been preparing for an apology for Christianity, which was never completed. . . . Although the Pensées appears to consist of ideas and jottings, some of which are incomplete, it is believed that Pascal had, prior to his death in 1662, already planned out the order of the book and had begun the task of cutting and pasting his draft notes into a coherent form.

Malcolm Muggeridge has stated that this was the unique appeal of the book: that it was jumbled and incomplete: notes for a later intended book that was never organized or edited in any final form by the author. And that is how the arguments from 501 Biblical Arguments Against Sola Scriptura can be seen: numbered “notes” that were later systematically compressed into a more compact book, with a conventional editor (Todd Aglialoro at Catholic Answers, who also edited three of my four bestselling books: A Biblical Defense of Catholicism, The Catholic Verses, and The One-Minute Apologist.

The following material comes from the first section, entitled, “The Binding Authority of Tradition” (all Bible passages: RSV).

*****

[No. 58] I would strongly contend that Paul (and all the apostles) casually assumed that the message they were delivering (orally, in most instances) was infallible. There is certainly no indication that they regarded it as fallible. When Paul spoke of receiving such traditions, he showed no indication whatever that it was fallible or that he questioned it because it came from oral transmission rather than written. Thus he appears to easily assume and take for granted that which many Protestants have the hardest time grasping and accepting, even when it is staring him right in the eye on the pages of the very Scripture that he grants the highest inspired authority (as Catholics do).

***

[No. 63] No one would be foolish enough to claim that every sermon and plea and prophetic warning of Jeremiah or any of the other prophets was recorded in writing and preserved in the Bible. In one long night alone, if Jeremiah had kept talking, that would add up to more words than we have in the entire book named for him. If this had been the “word of the Lord,” it would not have been recorded, just as, for example, Jesus’ words explaining the messianic prophecies concerning Himself, to the two disciples on the road to Emmaus, were not recorded, but they were true, and inspired, since they came from Jesus Himself (see Luke 24:26-27). The hearers of both Jeremiah and Jesus were bound to obey their words. Thus, the words carried a binding authority before they were written down and regardless of whether they were ever later written down.

***

[No. 66] An inspired biblical book might cite any number of non-inspired books as true, insofar as the portion cited is concerned. That’s exactly what happened in Jude 14-15, where 1 Enoch 1:9 is directly quoted (as the footnote for this verse in my Oxford Annotated RSV Bible states), and is described by the apostle as that which Enoch “prophesied.” Whether that counts as “inspired” or not, on that basis, I don’t know, and I’ll leave that technical question for the appropriate scholars to decide. But it is perfectly reasonable to conclude that what is cited is true, and an instance of true prophecy not different in kind from a prophecy of Jeremiah or Isaiah: whose prophecies are recorded in inspired Old Testament Scripture. And that’s just the point, isn’t it? If Jeremiah’s prophecy is regarded as inspired because it is in the Bible (OT), then Enoch’s must likewise be, because it is in the Bible (NT). Therefore an “extrabiblical tradition” was “acknowledged by the New Testament writers,” and my contention is unassailable.

***

[No. 68] Ananias, the high priest, was a Sadducee, and, according to The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, a scoundrel: “lawless and violent . . . haughty, unscrupulous, filling his sacred office for purely selfish and political ends” (vol. 1, p. 129). But Paul thought he had authority. Paul showed him respect, even when the latter had him struck on the mouth, and was not dealing with matters strictly of the Old Testament and the Law, but with the question of whether Paul was teaching wrongly and should be stopped (Acts 23:1-5). So here is a case of the high priest, who sacrifices at the Temple, being granted authority by the Apostle Paul. And he was not of exemplary character, which disposes of the argument that Jesus strictly limited Pharisaical authority, because some of them were bad men, and because He sternly rebuked them for hypocrisy. Moreover, the Sadducees were on a lower theological plane than the Pharisees, and adopted “liberal” or dissenting views on many doctrines which Pharisees and Christians alike accepted. But Paul still thinks they have authority!

***

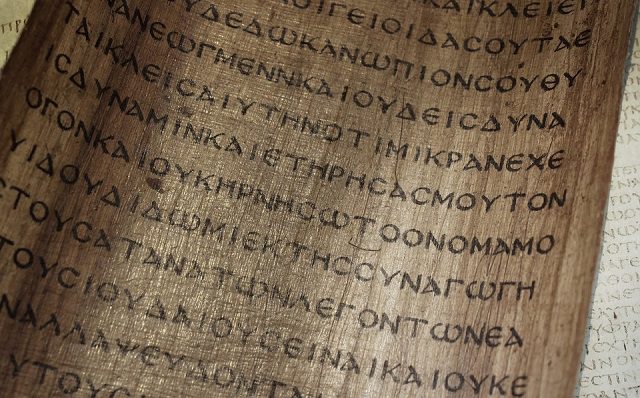

[No. 69] The terminology “Word of God” or “Word of the Lord” proves beyond any doubt that what is being referred to is a true tradition. It encompasses both written and verbal, oral delivery. The Bible states, for example: “Samaria had received the word of God” (Acts 8:14). This wasn’t some Bible society or the Gideons or a Billy Graham rally. There were no copies of Scripture involved at all. Samaria had responded to the preaching of Philip (Acts 8:5-6). Indeed, it couldn’t have been a matter of Scripture, because this was the gospel of Christ, which was only implicitly and darkly contained in the Old Testament, and the New Testament was not yet compiled or (mostly) even written; nor was Philip one of the inspired writers when it was written and compiled. St. Paul believes the same thing, and assumes that the “word of God” is an oral proclamation: “You received the word of God, which you heard from us” (1 Thessalonians 2:13). Now, unless one assumes that Paul only spoke to the Thessalonians the things which were later recorded in his two epistles to them (which is beyond silly, Paul could speak / read his entire two letters to them in maybe 15 minutes), then this involved more than Scripture.

***

[No. 71] Paul, in 1 Corinthians 14, repeatedly teaches about prophecy (prophesying). Obviously, if there was any significant amount of prophecy given, only an extremely small portion of it made it into the New Testament, if at all, because the New Testament is a pretty small book: about as long as an average-sized novel. So there were many oral messages by apostles and prophets and evangelists that would have been inspired, but ultimately non-biblical, just as was the case with our Lord Jesus. The New Testament refers several times to non-recorded speeches or acts of Jesus (Mk 4:33; 6:34; Lk 24:15-16,25-27; Jn 20:30; 21:25; Acts 1:2-3). It’s the most elementary common sense. Prophecy was rather common in New Testament or apostolic times (Acts 2:18). The Ephesians did it (Acts 19:6), as did the daughters of Philip (Acts 21:9), and the Corinthians (aforementioned passages and 1 Cor 11:4-5). There were even prophets (in terms of a calling or office), in addition to folks who prophesied on occasion. Prophets were listed in lists of ministries (1 Cor 12:28-29; Eph 4:11), and worked with teachers, as in Antioch (Acts 13:1). They both proclaimed and predicted (see, e.g., Agabus: Acts 11:28; 21:10-11). Prophets exhorted believers (Acts 15:32) and provided edification (1 Cor 14:3). Prophecy is described as revelation (1 Cor 14:30) and as connected with the Holy Spirit (plausible implication of 1 Thess 5:19-20). Prophets were subject to the norm of New Testament or apostolic tradition (1 Cor 14:29,37-38), just as the Old Testament prophets had to be in conformity with the Law of Moses.

***

[No. 80] Many Protestants think that “if Paul said it, even if it is oral (though this is not a tradition, of course), then it is binding, and will (almost always) be recorded in Scripture later, anyway, so we know exactly what Paul was telling them.” None of this is at all certain. Besides, this epistle was actually from Silvanus and Timothy also (see 2 Thess. 1:1). He (as primary author) often uses the plural “we” or “us” (see, e.g., 1:3-4,11, 2:1,13). Thus, in the passage under consideration, Paul is not only considering his own instruction authoritative, but also that of Silvanus and Timothy (“traditions which you were taught, whether by word of mouth or by letter from us“). This undercuts much of the “Paul as the pastor of the Thessalonians” contextual argument. This plurality is reiterated again by Paul:

2 Thessalonians 3:6-7 Now we command you, brethren, in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, that you keep away from every brother who is living in idleness and not in accord with the tradition that you received from us. For you yourselves know how you ought to imitate us; we were not idle when we were with you,

So we see that this tradition was larger than simply Paul’s own teaching, to be recorded in the Bible, and there alone, without one whit of it being transmitted in any other fashion. Thus Jude (3) can speak of “the faith which was once for all delivered to the saints.” What faith? By whom? This was not just Paul and it was not the New Testament. It was already known and was proclaimed by the apostles, in its fullness (Matthew 28:20 – see particularly the word “all”). This is not sola Scriptura, pure and simple. Catholics agree that Scripture contained this deposit, but not all of it explicitly or not absolutely every jot and tittle of apostolic tradition. If the Protestant says we are not bound to anything not found explicitly in Scripture, we ask them where in Scripture do we find such a notion, and why should we think ourselves in a better place than the earliest Christians, before the New Testament was compiled? Paul and the other apostles show no indication whatever that pre-New Testament Christians were somehow in a less-prepared or equipped position vis-a-vis Christianity than us “Bible Christians” today are. Sola Scriptura is unbiblical and unhistorical mythology.

***

Photo credit: Robert_C (9-20-16) [Pixabay / Pixabay License]

***

Summary: I have highlighted seven biblical arguments for the binding authority of tradition from my original manuscript, 501 Biblical Arguments Against Sola Scriptura.

***