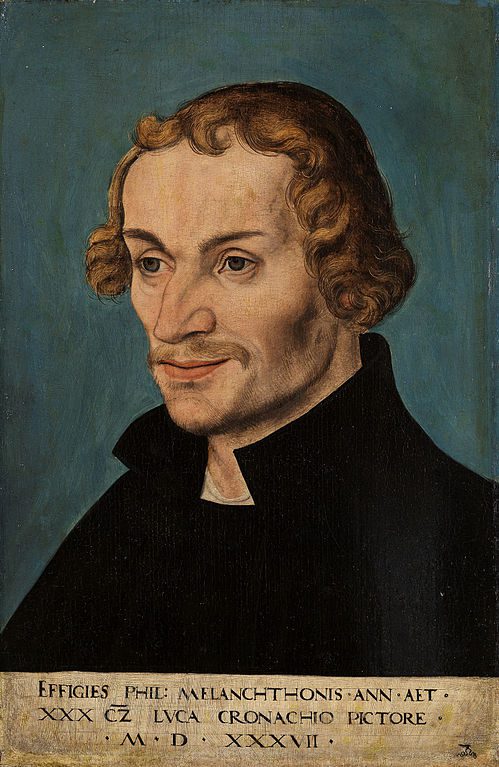

Portrait of Philipp Melanchthon (1537), by Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472-1553) [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

***

(1-28-04)

***

The words in blue are from Dr. Edwin Tait: an Anglican Church historian.

*****

I asked Dave about this, and he gave me a reference to a letter of Melanchthon’s in which Melanchthon said that he knew Augustine didn’t fully support the Protestant view but cited him as a supporter because of Augustine’s accepted authority. I have not looked at the context of this,

Here is the entirety of what I have in one of my papers:

Philip Melanchthon, in his letter to Johann Brenz (May 1531), illustrates how the Protestants had departed from patristic precedent:

Avert your eyes from such a regeneration of man and from the Law and look only to the promises and to Christ . . . Augustine is not in agreement with the doctrine of Paul, though he comes nearer to it than do the Schoolmen. I quote Augustine as in entire agreement, although he does not sufficiently explain the righteousness of faith; this I do because of public opinion concerning him.

(in Hartmann Grisar, Luther, six volumes, translated by E.M. Lamond, edited by Luigi Cappadelta, London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., 2nd edition, 1914, vol. 4, 459-460)

Grisar, on p. 459, states that “The letter was written by Melanchthon to Johann Brenz, but it had the entire approval of Luther, who even appended a few words to it. While clearly throwing overboard Augustine, it is nevertheless anxious to retain him.”

The documentation Grisar gives is “end of May, 1531”, Luthers Briefwechsel, 9, p. 18. This eleven-volume work was edited by L. Enders: Frankfurt & Stuttgart, 1884-1907; also 12 volumes, edited by G. Kawerau, Leipzig, 1910. Or is that also a biased source, since it is probably Lutheran and thus tilted toward Luther? :-)

and I’m not sure if it is quite as underhanded as Dave makes it sound.

I didn’t make it “sound” anything at all. I merely quoted the portion of the letter that I have, from Grisar.

The Reformers clearly did believe that Augustine’s view of grace was in important points coincident with their own, and that Augustine contradicted what most of their Catholic opponents were saying was the Catholic view.

And they also increasingly recognized that Augustine disagreed with key points of their theology as well. Grisar also cites Julius Kostlin (a well-known Protestant Luther scholar). He cites him as saying:

Luther could, indeed, appeal to St. Augustine in support of the thesis that man becomes righteous and is saved purely by God’s gracious decree and the working of His Grace and not by any natural powers and achievements, but not for the further theory that man is regarded by God as just purely by the virtue of faith . . . nor that the Christian thus justified can never perform anything meritorious in God’s sight but is saved merely by the pardoning grace of God which must ever anew be laid hold of by faith . . . Only gradually did the fundamental difference between the Augustinian view, his own and that of Paul become entirely clear to Luther.

(Grisar, ibid., IV, 458; citing Kostlin, Martin Luther. Sein Leben und seine Schriften, 5th ed., continued after Kostlin’s death by G. Kawerau, 2 volumes, Berlin, 1903; quotation from vol. 1, 138. I located a biography of Luther by Kostlin online at the Project Gutenberg website. I believe this is an earlier edition of the same work.

Of course, this doesn’t verify any deliberate botching of texts (I have not ever claimed that, and I believe I made this clear in our private correspondence), but it shows that Luther was indeed aware that his theology was diverging from St. Augustine’s. I found the following statement in this online book (by Julius Kostlin):

Herein also Luther found the theology of St. Augustine in accord

with the testimony of the great Apostle. While studying that

theology, his conviction of the power of sin and the powerlessness

of man’s own strength to overcome it, grew more and more decided.

But St. Paul taught him to understand that belief somewhat

differently to St. Augustine. To Luther it was not merely a

recognition of objective truths or historical facts. What he

understood by it, with a clearness and decision which are wanting in

St. Augustine’s teaching, was the trusting of the heart in the mercy

offered by the message of salvation, the personal confidence in the

Saviour Christ and in that which He has gained for us. With this

faith, then, and by the merits and mediation of the Saviour in whom

this faith is placed, we stand before God, we have already the

assurance of being known by God and of being saved, and we are

partakers of the Holy Spirit, who sanctifies more and more the inner

man. According to St. Augustine, on the contrary, and to all

Catholic theologians who followed his teaching, what will help us

before God is rather that inward righteousness which God Himself

gives to man by His Holy Spirit and the workings of His grace, or,

as the expression was, the righteousness infused by God. The good,

therefore, already existing in a Christian is so highly esteemed

that he can thereby gain merit before the just God and even do more

than is required of him. But to a conscience like Luther’s, which

applied so severe a standard to human virtue and works, and took

such stern count of past and present sins, such a doctrine could

bring no assurance of forgiveness, mercy, and salvation. It was in

faith alone that Luther had found this assurance, and for it he

needed no merits of his own. The happy spirit of the child of God,

by its own free impulse, would produce in a Christian the genuine

good fruit pleasing in God’s sight. It was a long time before Luther

himself became aware how he differed on this point from his chief

teacher amongst theologians. But we see the difference appear at the

very root and beginning of his new doctrine of salvation; and it

comes out finally, based on apostolic authority, clear and sharp, in

the theology of the Reformer.

Grisar gives a bit more evidence of the relationship of early Lutheranism to St. Augustine:

Against any citation of St. Augustine the Lutheran theologians and preachers in Pomerania protested during the negotiations for the formula of Concord. By thus falsely alleging this Father, they said in their declaration at the Synod of Stettin in 1577, a formidable weapon was placed in the hands of their Catholic opponents of which they had not failed to avail themselves against the Protestants; they were also assuming the responsibility for a public lie: “Augustine’s book De spiritu et littera teaches concerning Justification what the Papists teach today.” In the following year they declared against the form of the first Confessio Augustana, as published in Wittenberg in 1531 by Luther and our other fathers,” again on the ground that “there Augustine’s consensus is alleged.” In Mecklenburg the strictures of the Synods of Pomerania were accepted as perfectly warranted. (Grisar, ibid., IV, 461)

(In this section Grisar was quoting well-known Catholic historian Johann Joseph Ignaz von Dollinger: Die Reformation, 3 volumes, Ratisbon: 1846-1848, III, 370)

That being the case, they were not above claiming Augustine and neglecting to make it clear that the agreement was not total.

. . . which is all I and Grisar have stated. So where is the beef? By all means go look at the letter yourself and then report back to us.

. . . Dave did not apparently read Melanchthon’s letter as a whole.

That is correct, as I did not have access to Luther’s correspondence in German, nor could I read German if I did. Maybe this letter is in the English edition?

I will look at the letter in question when next I have access to Melanchthon’s letters in the Corpus Reformatorum.

Please do so, and I want as full a citation as possible. You want to press this point, so face the music if it comes out the way that it appears, from what we know thus far. It probably won’t prove deliberate mis-quoting, but I think it will show that there was misrepresentation going on.

At any rate, Dave did not provide me with any evidence for outright fabrication.

That is correct.

The most the Melanchthon letter means is that at least one Reformer was willing to exaggerate the degree of Augustine’s agreement with him for polemical purposes.

Correct again, except that, since Luther agreed with the letter and added to it, and since it appears in the collection of his own correspondence, that means at least two “Reformers” did so (including the most important one of all).

Lastly, we find in Luther’s Table-Talk the following slams against St. Augustine and the Fathers:

Behold what great darkness is in the books of the Fathers concerning faith . . . Augustine wrote nothing to the purpose concerning faith. (DXXVI)

The more I read the books of the Fathers, the more I find myself offended. (DXXX)

Jerome should not be numbered among the teachers of the church, for he was a heretic. (DXXXV)

(edition translated by William Hazlitt, Philadelphia: Lutheran Publication Society, n.d., 286-289)

I don’t see anything in any of the above that would disabuse me or any Catholic from the notion that the Protestants departed from the Fathers to a great extent, particularly from St. Augustine. The Catholic Church is far more the legatee of Augustine than Reformed Protestantism.

I found a website where one Michael J. Vlach is reviewing Alister E. McGrath’s book, Iustitia Dei: A History of the Christian Doctrine of Justification (2d. ed, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998).

Here are some interesting comments showing that Protestantism departed from Augustine at several key points:

McGrath refers repeatedly to the enormous significance of Augustine on soteriology. He points out that Augustine is the first major theologian of church history to seriously address the issue of justification (24). Although Augustine’s views would undergo development and change in his own lifetime, many of his positions would eventually become predominant in the medieval era.

Some of Augustine’s key views according to McGrath include:

· Man’s election is based on God’s eternal decree of predestination.

· Free will is not lost; it is merely incapacitated and may be healed by grace.

· The act of faith is a divine gift.

· Faith is adherence to the Word of God.

· It is love, not faith, that is the power that brings about conversion.

· There is a distinction between operative and cooperative grace.

· The righteousness of God is that by which God justifies sinners.

· God’s prevenient grace prepares man’s will for justification.In specific relation to justification, Augustine held the following:

· The motif of amor Dei dominates Augustine’s theology of justification.

· The verb ‘to justify’ means ‘to make righteous.’ Thus, justification is about being ‘made just.’

· Justification is all-embracing, including both the event of justification and the process of justification.

· Man’s righteousness in justification is inherent rather than imputed.The predominant view of justification in the medieval era was this: “Justification refers not merely to the beginning of the Christian life, but also to its continuation and ultimate perfection, in which the Christian is made righteous in the sight of God and the sight of men through a fundamental change in his nature, and not merely his status” (41). With this understanding, there was no distinction between justification and sanctification that would later characterize Reformation orthodoxy. Other views associated with the medieval era according to McGrath include:

· The infusion of grace initiates a chain of events that eventually leads to justification.

· Justification consists in the remission of sins.

· Justification involves a real change in its object.

· Man has a positive role to play in his own justification.

· A human disposition toward justification is necessary.

· Justification takes place within the sphere of the church and is particularly associated with the sacraments of baptism and penance.

· Grace is understood in Augustinian terms, including the elements of restoration of the divine image, forgiveness of sins, regeneration, and indwelling of the Godhead.. . . McGrath does positively assert that the origins of the concept of imputed righteousness “lie with Luther” (201).

If this concept originated with Luther, it could hardly have also been the view of St. Augustine. I found another fascinating article in the excellent evangelical online journal, Quodlibet (which I have linked to on my website for several years now): “Justification as Healing: The Little-Known Luther,” by Ted M. Dorman.

Here are some relevant comments:

Reformed Protestantism’s historic distinction between the passive or imputed righteousness of Christ given in justification, and the active or infused righteousness given in sanctification, has its genesis in Luther’s thought. Prior to Luther justification had been tied to regeneration, so that the forgiveness of sins was viewed not merely as a forensic declaration of the believer’s status as righteous before God, but as a process whereby the believer is actually made righteous. In this way, as Alister McGrath has pointed out, Luther introduced a theological novum into the Western church tradition ‘which marks a complete break with the tradition up to this point.’ [1]

[Footnote 1: Alister McGrath, Iustitia Dei: A History of the Christian Doctrine of Justification. Two volumes. Cambridge University Press, 1986. See Volume I pages 182ff. and Volume II pages 2f. The quotation is from II:]

The Reformers did not deny the reality of infused righteousness. Indeed, they insisted that justifying (passive) righteousness never exists apart from sanctifying (active) righteousness. [2] At the same time, however, they made a ‘notional distinction’ between justification and sanctification where none had previously existed. [3]

[Footnote 2: John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion III.2.8. Footnote 3: McGrath, Iustitia Dei II.2]

. . . the earlier views of Luther, as opposed to his later views, are more in line with the pre-Reformation classical Christian consensus on justification . . .

[Footnote 8: This notion of a shift between Luther’s earlier and later positions on justification is generally rejected by Lutherans]

. . . A survey of Martin Luther’s writings between 1515 and 1521 reveals a doctrine of justification which in some ways bears more resemblance to Augustine’s teachings than those of the later Luther himself. This is not to say that Luther consciously followed Augustine; indeed, in 1545 he wrote that he formulated his early perspectives on justification before he had read Augustine on the subject.

. . . Some time after 1521 Luther’s ideas concerning the relationship between faith, justification, and obedience to God’s commands underwent significant revision. By the time he wrote his 1535 commentary on Galatians, Luther no longer emphasized obedience to God’s commandments as an expression of justifying faith. Instead, he divided justifying faith and obedience to God’s commandments into separate categories. The former he ascribed to the ‘passive righteousness of Christ’; the latter to the ‘active righteousness of the Law.’

[Footnote 24: Luther’s Works Volume 26, 9: ‘For between these two kinds of righteousness, the active righteousness of the Law and the passive righteousness of Christ, there is no middle {i.e., common} ground.’]

In the opening paragraphs of his 1535 Galatians commentary Luther explicitly divorces the commandments of God from the righteousness of faith. After identifying various kinds of ‘righteousness’ (political, ceremonial, parental, and moral) Luther goes on to say:

There is, in addition to these [various kinds of righteousness], yet another righteousness, the righteousness of the Law or of the Decalog, which Moses teaches. We, too, teach this, but after the doctrine of faith. . . . . Over and above all these there is the righteousness of faith or Christian righteousness, which is to be distinguished most carefully from all the others. For they are all contrary to this righteousness, both because they proceed from the laws of emperors, the traditions of the pope, and the commandments of God, and because they consist in our works and can be achieved by us . . . . But this most excellent righteousness, the righteousness of faith, which God imputes to us through Christ without works . . . . is quite the opposite; it is a merely passive righteousness, while all the others, listed above, are active. For here we work nothing, render nothing to God; we only receive and permit someone else to work in us, namely, God.

[Footnote 25: Luther’s Works Volume 26, 4f.]

. . . Whatever may have occasioned Luther’s shift in thinking between 1521 and 1535, it is a matter of historical record that after about 1530 the Protestant Reformers defined justification almost solely in forensic terms as the forgiveness of sins.

[Footnote 38: McGrath, Iustitia Dei II 2. See also McGrath’s comment on page 23 that Philip Melanchthon’s increasing emphasis on iustitia aliena from about 1530 onward provided the chief impetus to this shift. To what degree Melanchthon influenced Luther, or vice-versa, is beyond the scope of this study.]

. . . In addition to Luther, three classical Christian sources demonstrate that prior to the Reformation the Church viewed justification as both an event and a process. These three are Augustine, Anselm of Canterbury, and Thomas Aquinas.

Augustine’s influence on Luther and Calvin is difficult to overstate, especially with relation to the doctrine of total depravity . . . Yet Trent’s emphasis on justification as a process does find precedent in Augustine, perhaps Luther’s favorite classical theologian, who spoke of justification not merely as a singular event but also as a process ‘by which [God] justifies those who from unrighteousness He makes righteous.’

[Footnote 42: Sermon 131; cited in Thomas Oden, Life in the Spirit (San Francisco: HarperCollins, 1992), 125. See also Catechism of the Catholic Church (Mahwah, N.J.: Paulist Press 1994), 481ff. (Part Three, Chapter 3, Article 2). Also worthy of note here is that Augustine, like Luther a millennium later, spoke of Christ as a physician who heals our diseases (On the Spirit and the Letter chapters 9 and 10). A useful summary of Augustine’s doctrine of justification may be found in Norman Geisler and Ralph MacKenzie, Roman Catholics and Evangelicals: Agreements and Differences (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1995), 83-87.]

[ . . . ]

[Footnote 47: It must be noted that both Anselm and Aquinas followed Augustine in that neither entertained the Reformers’ notional distinction between justification and sanctification, and both tended to emphasize infused righteousness.]

Lastly, I looked up every single reference to St. Augustine in my copy of the Book of Concord (the doctrinal standard for Lutheranism). Without exception it claims that Augustine is in full agreement with Lutheran doctrine. Furthermore, it makes outright false factual claims, such as that Augustine denied ex opere operato (the notion that the sacraments have inherent power apart from the dispenser or recipient), purgatory, and (though not completely clear), baptismal regeneration. These are all erroneous judgments. Augustine wrote:

It is this one Spirit who makes it possible for an infant to be regenerated through the agency of another’s will when that infant is brought to Baptism . . . The water, therefore, manifesting exteriorly the benefit of grace, both regenerate in one Christ that man who was generated in one Adam.

(Letter to Bishop Boniface, 98, 2; A.D. 408; in Jurgens, William A., editor and translator, The Faith of the Early Fathers {FEF}, 3 volumes, Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1970, III, 4)

The Sacraments of the New Testament give salvation . . .

(Explanations of the Psalms, 73, 2; A.D. 418; in Jurgens, III, 19)

It is an excellent thing that the Punic Christians call Baptism itself nothing else but salvation, and the Sacrament of Christ’s Body nothing else but life. Whence does this derive, except from an ancient and, as I suppose, apostolic tradition, by which the Churches of Christ hold inherently that without Baptism and participation at the table of the Lord it is impossible for any man to attain either to the kingdom of God or to salvation and life eternal? This is the witness of Scripture too.

The Sacrament of Baptism is most assuredly the Sacrament of regeneration.

. . . there is a full remission of sins in Baptism.

(Forgiveness and the Just Deserts of Sins, and the Baptism of Infants, 1, 24, 34 / 2,

27, 43 /2, 28, 46; 412; in Jurgens, FEF, III, 91-93)

Luther and Augustine agree with regard to baptism, but (strangely), confessional Lutheranism seems to have become a bit confused about baptism and moves away from Luther’s traditionalism in that respect. As for purgatory, Augustine wrote:

The man who perhaps has not cultivated the land and has allowed it to be overrun with brambles has in this life the curse of his land on all his works, and after this life he will have either purgatorial fire or eternal punishment.

(Genesis Defended Against the Manicheans, 2, 20, 30. Jurgens, FEF, vol. 3, 38)

Temporal punishments are suffered by some in this life only, by some after death, by some both here and hereafter; but all of them before that last and strictest judgment. But not all who suffer temporal punishments after death will come to eternal punishments, which are to follow after that judgment.

(City of God, 21, 13. Jurgens, FEF, vol. 3, 105)

The prayer . . . is heard on behalf of certain of the dead; but it is heard for those who, having been regenerated in Christ, did not for the rest of their life in the body do such wickedness that they might be judged unworthy of such mercy, nor who yet lived so well that it might be supposed they have no need of such mercy.

(City of God, 21, 24, 2. Jurgens, FEF, vol. 3, 106)

That there should be some such fire even after this life is not incredible, and it can be inquired into and either be discovered or left hidden whether some of the faithful may be saved, some more slowly and some more quickly in the greater or lesser degree in which they loved the good things that perish, – through a certain purgatorial fire.

(Enchiridion of Faith, Hope and Love, 18,69, Jurgens, FEF, vol. 3, 149. See also — in the same work — 29,109-110; The Care That Should be Taken of the Dead, 1,3)

So we see the usual Protestant project of trying to co-opt the Fathers (above all, St. Augustine) for their purposes and views (in an effort to show that Protestantism is entirely “catholic” and in accord with the best of all previous Christian tradition), in the Book of Concord. But the attempt fails miserably, because, as we have seen, modern Protestant scholarship shows many profound differences between Protestantism and St. Augustine, particularly with regard to soteriology and justification in particular.

Does this mean that the Book of Concord and Philip Melanchthon (its primary author) were deliberately dishonest, and rascally scoundrels? I would not make that claim, and I don’t think so. Much more likely is that their Protestant and anti-Roman biases simply blinded them to certain facts and thus led to inaccuracies. Or they did inadequate research (there was no Internet in those days which gives someone like myself an ability to come up with relevant materials lightning-fast).

But whatever is true regarding their motives and intentions, the fact of erroneous presentation of St. Augustine as in entire agreement with Protestant distinctives is indisputable. We need go no further than McGrath (no slouch and no mean scholar) to see that very clearly.

I was originally responding to Mathitria’s claim that the Reformers were deliberately dishonest. When I asked you where Mathitria got this, you supplied me with this quote from Grisar. Which is why I referred to it as if you had intended it to prove deliberate deceit. It certainly does indicate Melanchthon’s use of some degree of “dissimulation” (to use a term Erasmus employed from time to time).

Indeed, and that is why I am quite curious to see if you can locate the entire letter and share it with us.

I wish this surprised me, but it doesn’t. Of course, this indicates how false the idea is that the Reformers were all about throwing theology open to ordinary people–they wanted to keep some of the tough issues away from the people just as much as any of their Catholic opponents.

Of course.

However, my point is that Melanchthon clearly did believe that Augustine was in more agreement with the Reformers than with their opponents–just not close enough. Luther held the same view. The Reformed sometimes did also, though generally they tended to be more positive about the Fathers (not what you would expect, but it seems to be the case).

They can believe this, but demonstrating it is another matter.

McGrath is certainly right that imputed righteousness is not in the Fathers, and Luther admitted this. However, the Reformers still believed that Augustine was on their side in some fundamental ways. And many of the self-proclaimed champions of Catholicism do seem to have been rather deaf to the Augustinian side of the tradition. Sadoleto’s commentary on Romans was in fact condemned at Rome for semi-Pelagianism, and I believe Pighius also had some trouble in this regard (these are two of Calvin’s more famous Catholic opponents). Unfortunately, Girolamo Seripando (general of the Augustinian Order) never went head to head with the Reformers, as far as I know. It would have been interesting to see what he would have said. Seripando is clearly more faithful to Augustine than Luther or Calvin. I’m not sure the same could be said of all the Catholic theologians of that era. And not all of Seripando’s Augustinian views were accepted at Trent.

It’s because there were lots of theories on justification flying around. People were confused. But someone like Aquinas wasn’t confused about the issue. Because the late Middle Ages was trying to move away from Aquinas and Scholasticism, we got all the semi-Pelagianism and other goofy mystical theories being bandied about. Too bad it took so long to get Trent to clarify things. But once it did it was brilliant.

Patristic scholarship was still only just getting off the ground at this point, and many of the best patristic scholars became Protestants. It wasn’t till the turn of the 17th century that Catholics recovered the edge. The Protestants did use a lot of bogus arguments to try to show that the Fathers were on their side. I agree with you that these arguments were probably mostly in good faith. I think people (of any viewpoint) often see what they want to see, and don’t see what they don’t want to see.

I don’t know all the details of the controversies leading up to the Formula of Concord. I don’t know off the top of my head which Lutheran camp the Pomeranians fall into, though they sound like hardline “Gnesio-Lutherans.” However, it would be a mistake to assume that they represent Lutheranism as a whole. On the contrary, they were clearly upset with the more general practice of claiming Augustine’s authority.

No one was saying they represent Lutheranism “as a whole.” My point in citing that was to show that even among Protestants there were parties who knew that Augustine was being inaccurately claimed as a precursor in some things. I saw it with my own eyes, looking through the Book of Concord. Now, I hope you discover the letter of Melanchthon and produce it here, so we can wrap this up.

I did look up the Melanchthon letter. It turned out to be quite interesting from the point of view of my dissertation (one recently completed–but still much-to-be-revised–chapter of which compares my guy Martin Bucer with Luther and Melanchthon on the subject of law vs. Gospel; some of the things Melanchthon is criticizing Brenz for are pretty much what Bucer said).

Yes; there is much more of soteriology in it than of Augustine and how he was viewed or utilized by the first Protestants.

I’ve translated Melanchthon’s entire letter and part of Brenz’s reply. My translation was pretty quick . . . I tried to err on the side of literalism, especially where theological concepts were being discussed.

Thanks for doing this; I appreciate it. Here it is (I broke it up in paragraphs myself — so that will not necessarily reflect original paragraphs — if there were any):

[Background and context: Melanchthon had written to Brenz on April 8, saying that he understood why Brenz, a newly married man, hadn’t written, but asking him to start corresponding again. He also sent some propositions about justification. Brenz must have commented on them in a letter not found in the collection of Melanchthon’s correspondence. In mid-May Melanchthon responded]:

I received your rather long letter, which I enjoyed very much. I beg you to write often and at length. Regarding faith, I have figured out what your problem is (1). You still hold on to that notion of Augustine’s, who gets to the point of denying that the righteousness of reason is reckoned for righteousness before God—and he thinks rightly. Next he imagines that we are counted righteous on account of that fulfillment of the Law which the Holy Spirit works in us. So you imagine that people are justified by faith, because we receive the Holy Spirit by faith, so that afterwards we can be righteous by the fulfillment of the law which the Holy Spirit works in us.

This notion places righteousness in our fulfillment, in our cleanness or perfection, even though this renewal must follow faith. But you should turn your eyes completely away from this renewal and from the law, and toward the promise and Christ, and you should think that we are righteous, that is, accepted before God, and find peace of conscience, on account of Christ, and not on account of that renewal. For this new quality itself does not suffice. Therefore we are righteous by faith alone, not because it is the root, as you write, but because it lays hold of Christ, on account of whom we are accepted, whatever this new life (2) may be like—indeed it follows necessarily, but it does not give the conscience peace.

Therefore love, which is the fulfillment of the law, does not justify, but faith alone, not because it is a certain perfection in us, but only because it lays hold of Christ. We are righteous, not on account of love, not on account of the fulfillment of the law, not on account of our new life, even though these things are the gifts of the Holy Spirit, but on account of Christ; and we lay hold of this only through faith.

Augustine does not fully accord with (3) Paul’s pronouncement, even though he gets closer to it than the Scholastics. And I cite Augustine as fully agreeing with us (4) on account of the public conviction about him, even though he does not explain the righteousness of faith well enough. Believe me, dear Brenz, the controversy about the righteousness of faith is great and obscure. Nonetheless, you will understand it rightly if you totally take your eyes away from the law and Augustine’s notion about the fulfillment of the law, and fix your mind rather on the free promise, so that you think that we are righteous (that is, accepted) and find peace on account of the promise and on account of Christ. This pronouncement is true and makes Christ’s glory shine forth and wonderfully raises up [people’s] consciences. I have tried to explain it in the Apology, but it was not possible to speak in the same way there as I do now because of the calumnies of our opponents, even though I am saying the same thing essentially. (5)

When would the conscience have peace and a sure hope if it had to think that we are only counted righteous when that new life has been made perfect within us? What is this other than to be justified on the basis of the law, not the free promise? In the disputation I said this: that to attribute justification to love is to attribute justification to our work. There I have in mind the work done by the Holy Spirit in us. For faith justifies, not because it is a new work of the Holy Spirit in us, but because it lays hold of Christ, on account of whom we are accepted, not on account of the gifts of the Holy Spirit in us.

If you will consider that the mind must be brought back from Augustine’s notion, you will easily understand the issue. Also, I hope to help you in some way by means of our apology, even if I speak cautiously of such things, which however cannot be understood except in the conflict of the conscience. The people indeed ought to hear the preaching of law and repentance; but meanwhile this true pronouncement of the Gospel must not be passed over. I ask you to write again, and let me know your judgment about this letter and the apology—whether this letter has satisfactorily answered your question. Farewell.

Phil. Mel.

Luther’s P.S.

And I, dear Brenz, in order to get a better grip on this issue frequently imagine it this way: as if in my heart there is no quality that is called faith or charity, but instead of them I put Christ himself and say: this is my righteousness; He is the quality and my formal righteousness, as they call it. In this way I free myself from the perception (6) of the law and works, and even from the perception of this object, Christ (7), who is understood as a teacher or a giver; but I want Him to be my gift and teaching in Himself, so that I may have all things in Him. (8) So he says: I am the way, the truth and the life. He does not say: I give you the way, the truth and the life, as if He worked in me while being placed outside of me. He must be such things in me, remain in me, live in me, speak not through me but into me (9), 2 Cor. 5; so that we may be righteousness in Him, not in love or in gifts that follow.

Footnotes

(1) Lit. “I hold/grasp what exercises you/should excercise you/might exercise you”.

(2) Lit. newness.

(3) Lit., does not satisfy.

(4) Melanchthon uses a Greek word which means “one who says the same”; “with us” is my addition since it’s understood in the original.

(5) Lit. in the thing/matter itself.

(6) Latin: ab intuitu.

(7) Or in another reading, this objective Christ.

(8) “Object” means “object of thought”—Luther’s point is that he doesn’t even think of Christ as a source of teaching or of gifts, such as the gift of charity.

(9) Luther uses the Greek here.

I think this correspondence makes it clear that there were disagreements among the Reformers about just how authoritative Augustine was and how close their teaching was to his. While Brenz’s letter to which Melanchthon took exception appears to have been lost (or perhaps just hasn’t been edited), his reply makes a very Augustinian point, namely that faith is itself a work. I would also say that Bucer, on whom I’m writing my dissertation, is more Augustinian (and in places even Thomist) than many of the other Reformers. Which I don’t think contradicts anything you were saying.

No; I would expect differences on the continuum.

But the impression you gave, at least as quoted by Mathitria, was that the Reformers as a whole could not justify their views by the Fathers and realized not only that they couldn’t but that this was a serious problem, so they resulted to dishonesty to cover it up.

The claim of my earlier paper was simply: “the Protestants had departed from patristic precedent.” That is certainly an unarguable statement as it stands (people like McGrath and Oberman and Pelikan and Kelly establish it beyond all doubt — even Norman Geisler, when he admits that imputed justification was unknown from the time of Paul to that of Luther). I said nothing about dishonesty — let alone deliberate dishonesty. I simply cited the portion of the letter that Grisar had and let the reader decide for himself how to interpret it. My view, as it turns out, is identical to your own: it wasn’t deliberate lying or deception, but a certain “playing fast and loose with the facts”:

They were not above claiming Augustine and neglecting to make it clear that the agreement was not total.

The most the Melanchthon letter means is that at least one Reformer was willing to exaggerate the degree of Augustine’s agreement with him for polemical purposes.

It certainly does indicate Melanchthon’s use of some degree of “dissimulation” . . .

So we agree on that, and nothing in the letter as a whole suggests otherwise. Therefore, Grisar was not citing it in a hyper-polemical, unscholarly way himself. As far as I am concerned, he is vindicated, at least insofar as pertains to his use of this letter. You claimed he was so biased that I shouldn’t have trusted him to even accurately present a portion of a letter. We continue to disagree on that. If you wish to show that Grisar was so polemical and “anti-Luther” that he can’t be trusted, you will have to show it elsewhere. I get tired of hearing this claim from Protestants, but never seeing any hard evidence of it. So the weariness concerning the use and/or abuse of Grisar works both ways, methinks.

Please bear in mind that my initial issue was not with what you actually said but with what Mathitria was saying.

I understand that, but you raised larger issues about Grisar and apologetic / historiographical methodology, which I felt were important to deal with.

He cited you as an authority, and it is clear that he cited you incorrectly.

It may have been a problem of terminology. We probably don’t need to blame Mathitria anymore than we need to blame Melanchthon. The important thing is to get to the facts. If I hadn’t cited this particular letter from Grisar, you probably would have never heard of it or read it — let alone learned something about Melanchthon and Luther’s relationship to Augustine. So see, we do work together after all, and you and I agree about Melanchthon’s (and Luther’s) view of Augustine. And we appear to agree with the interpretation of a guy like McGrath, who represents current-day scholarship.

Note, however, that McGrath also backs up Grisar’s main point in all this: that Augustine’s view was different from the early Protestants, and that this was underplayed and ignored in documents such as the Book of Concord. That was always his beef (and mine), because it (yet again) cuts through the nonsense of early Protestantism supposedly returning to the patristic teachings. One can’t return to something that never was. That makes Protestantism a revolution, not a reform, and this is what I have always held, since my conversion in 1990.

You went and found the actual letter in question, and what it showed was exactly what I (and Grisar) claimed for it in the beginning. So there was nothing even methodologically questionable here. I simply quoted a letter from a secondary source (but that source was a reputable historian and author of a six-volume work on one man).

*****

Meta Description: The earliest Protestants often sought to “co-opt” Augustine for their cause, but not infrequently they would “throw him under the bus” if he disagreed with their novelties.

Meta Keywords: St. Augustine, patristics, patrology, Church fathers, Fathers of the Church, Luther & Augustine, Protestants & Augustine, Reformers & Augustine, Calvin & Augustine, Melanchthon & Augustine