Chapel of Saint Ananias in Damascus, Syria, is believed to be the remains of the home of Ananias, who baptized St. Paul. Archaeological excavations in 1921 found the remains of a Byzantine church from the 5th or 6th century. Photograph by Titoni Thomas (2006) [Wikimedia Commons / Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license]

***

(12-11-09)

*****

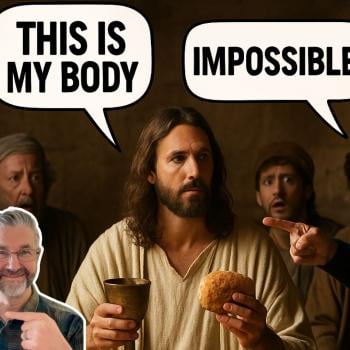

John Calvin described the Sacrifice of the Mass as an “abomination unknown to the purer Church,” and stated that “this perverse course was unknown to the purer Church. . . . it is absolutely certain that all antiquity is opposed to them, as . . . may be more surely known by the diligent reading of the Fathers” (Institutes, IV, 18:9). Contrary to Calvin’s puerile, historically revisionist rhetoric, however, there is in fact a great deal of patristic support for the Catholic position on this matter (and this data is confirmed by reputable Protestant Church historians, as seen below):

The Didache

Assemble on the Lord’s day, and break bread and offer the Eucharist; but first make confession of your faults, so that your sacrifice may be a pure one. Anyone who has a difference with his fellow is not to take part with you until he has been reconciled, so as to avoid any profanation of your sacrifice [Matt. 5:23–24]. For this is the offering of which the Lord has said, ‘Everywhere and always bring me a sacrifice that is undefiled, for I am a great king, says the Lord, and my name is the wonder of nations’ [Mal. 1:11, 14]. (Didache 14 [A.D. 70] )

St. Clement of Rome

Our sin will not be small if we eject from the episcopate those who blamelessly and holily have offered its sacrifices. Blessed are those presbyters who have already finished their course, and who have obtained a fruitful and perfect release. (Letter to the Corinthians 44:4–5 [A.D. 80] )

St. Ignatius of Antioch

Make certain, therefore, that you all observe one common Eucharist; for there is but one Body of our Lord Jesus Christ, and but one cup of union with his Blood, and one single altar of sacrifice—even as there is also but one bishop, with his clergy and my own fellow servitors, the deacons. This will ensure that all your doings are in full accord with the will of God. (Letter to the Philadelphians 4 [A.D. 110] )

St. Justin Martyr

God speaks by the mouth of Malachi, one of the twelve [minor prophets], as I said before, about the sacrifices at that time presented by you: ‘I have no pleasure in you, says the Lord, and I will not accept your sacrifices at your hands; for from the rising of the sun to the going down of the same, my name has been glorified among the Gentiles, and in every place incense is offered to my name, and a pure offering, for my name is great among the Gentiles . . . [Mal. 1:10–11]. He then speaks of those Gentiles, namely us [Christians] who in every place offer sacrifices to him, that is, the bread of the Eucharist and also the cup of the Eucharist. (Dialogue with Trypho the Jew 41 [A.D. 155] )

St. Irenaeus

He took from among creation that which is bread, and gave thanks, saying, ‘This is my body.’ The cup likewise, which is from among the creation to which we belong, he confessed to be his blood. He taught the new sacrifice of the new covenant, of which Malachi, one of the twelve [minor] prophets, had signified beforehand: ‘You do not do my will, says the Lord Almighty, and I will not accept a sacrifice at your hands. For from the rising of the sun to its setting my name is glorified among the Gentiles, and in every place incense is offered to my name, and a pure sacrifice; for great is my name among the Gentiles, says the Lord Almighty’ [Mal. 1:10–11]. By these words he makes it plain that the former people will cease to make offerings to God; but that in every place sacrifice will be offered to him, and indeed, a pure one, for his name is glorified among the Gentiles. (Against Heresies, IV, 17, 5)

Inasmuch, then, as the Church offers with single-mindedness, her gift is justly reckoned a pure sacrifice with God. . . . For it behoves us to make an oblation to God, . . . the Church alone offers this pure oblation to the Creator, . . . (Against Heresies, IV, 18, 4; ANF, Vol. I)

For we offer to Him His own, announcing consistently the fellowship and union of the flesh and Spirit. For as the bread, which is produced from the earth, when it receives the invocation of God, is no longer common bread, but the Eucharist, consisting of two realities, earthly and heavenly; so also our bodies, when they receive the Eucharist, are no longer corruptible, having the hope of the resurrection to eternity. (Against Heresies, IV, 18, 5; ANF, Vol. I)

St. Cyprian of Carthage

If Christ Jesus, our Lord and God, is himself the high priest of God the Father; and if he offered himself as a sacrifice to the Father; and if he commanded that this be done in commemoration of himself, then certainly the priest, who imitates that which Christ did, truly functions in place of Christ. (Letters 63:14)

St. Hilary of Poitiers

Hilary, for example, describes [Tract. in ps. 68, 19] the Christian altar as ‘a table of sacrifice’ and speaks [Ib. 68, 26] . . . of the immolation of the paschal lamb made under the new law. (J. N. D. Kelly, Early Christian Doctrines, San Francisco: Harper & Row, fifth revised edition, 1978, 453)

St. Basil the Great

It is good and beneficial to communicate every day, and to partake of the holy body and blood of Christ. . . . once the priest has completed the offering . . . (Letter XCIII, To the Patrician Cæsaria; NPNF 2, Vol. VIII)

St. Cyril of Jerusalem

Then, after the spiritual sacrifice, the bloodless service, is completed, over that sacrifice of propitiation we entreat God for the common peace of the Churches, for the welfare of the world; for kings; for soldiers and allies; for the sick; for the afflicted; and, in a word, for all who stand in need of succour we all pray and offer this sacrifice. (Catechetical Lecture XXIII, 7-8; NPNF 2, Vol. VII)

St. Ambrose

We saw the prince of priests coming to us, we saw and heard him offering his blood for us. We follow, inasmuch as we are able, being priests, and we offer the sacrifice on behalf of the people. Even if we are of but little merit, still, in the sacrifice, we are honorable. Even if Christ is not now seen as the one who offers the sacrifice, nevertheless it is he himself that is offered in sacrifice here on Earth when the body of Christ is offered. Indeed, to offer himself he is made visible in us, he whose word makes holy the sacrifice that is offered. (Commentaries on Twelve Psalms of David 38:25)

St. John Chrysostom

Christ is present. The One who prepared that [Holy Thursday] table is the very One who now prepares this [altar] table. For it is not a man who makes the sacrificial gifts become the Body and Blood of Christ, but He that was crucified for us, Christ Himself. The priest stands there carrying out the action, but the power and grace is of God. “This is My Body,” he says. This statement transforms the gifts. (Homilies on the Treachery of Judas, 1, 6; in William A. Jurgens, editor and translator, The Faith of the Early Fathers, three volumes, Collegeville, Minnesota: Liturgical Press, Vol. II, 1970, 104-105)

When you see the Lord immolated and lying upon the altar, and the priest bent over that sacrifice praying, and all the people empurpled by that precious blood, can you think that you are still among men and on earth? Or are you not lifted up to heaven? (The Priesthood 3:4:177)

Reverence, therefore, reverence this table, of which we are all communicants! Christ, slain for us, the sacrificial victim who is placed thereon! (Homilies on Romans 8:8)

In ancient times, because men were very imperfect, God did not scorn to receive the blood which they were offering . . . to draw them away from those idols; and this very thing again was because of his indescribable, tender affection. But now he has transferred the priestly action to what is most awesome and magnificent. He has changed the sacrifice itself, and instead of the butchering of dumb beasts, he commands the offering up of himself. (Homilies on First Corinthians, 24:2)

What then? Do we not offer daily? Yes, we offer, but making remembrance of his death; and this remembrance is one and not many. How is it one and not many? Because this sacrifice is offered once, like that in the Holy of Holies. This sacrifice is a type of that, and this remembrance a type of that. We offer always the same, not one sheep now and another tomorrow, but the same thing always. Thus there is one sacrifice. By this reasoning, since the sacrifice is offered everywhere, are there, then, a multiplicity of Christs? By no means! Christ is one everywhere. He is complete here, complete there, one body. And just as he is one body and not many though offered everywhere, so too is there one sacrifice. (Homilies on Hebrews 17:3 [6])

St. Jerome

According to Jerome [Ep. 114, 2], the dignity of the eucharistic liturgy derives from its association with the passion; it is no empty memorial, for the victim of the Church’s daily sacrifice is the Saviour himself. [Ib. 21, 26] (in Kelly, ibid., 453)

St. Augustine

Because there was there a sacrifice after the order of Aaron, and afterwards He of His Own Body and Blood appointed a sacrifice after the order of Melchizedek; He changed then His Countenance in the Priesthood, and sent away the kingdom of the Jews, and came to the Gentiles. . . . (Exposition on Psalm XXXIV, 1; NPNF 1, Vol. VIII)

Chapter 20.—Of the Supreme and True Sacrifice Which Was Effected by the Mediator Between God and Men.

And hence that true Mediator, in so far as, by assuming the form of a servant, He became the Mediator between God and men, the man Christ Jesus, though in the form of God He received sacrifice together with the Father, with whom He is one God, yet in the form of a servant He chose rather to be than to receive a sacrifice, that not even by this instance any one might have occasion to suppose that sacrifice should be rendered to any creature. Thus He is both the Priest who offers and the Sacrifice offered. And He designed that there should be a daily sign of this in the sacrifice of the Church, which, being His body, learns to offer herself through Him. Of this true Sacrifice the ancient sacrifices of the saints were the various and numerous signs; and it was thus variously figured, just as one thing is signified by a variety of words, that there may be less weariness when we speak of it much. To this supreme and true sacrifice all false sacrifices have given place. (City of God, Book X, 20; NPNF 1, Vol. II)

For then first appeared the sacrifice which is now offered to God by Christians in the whole wide world, and that is fulfilled which long after the event was said by the prophet to Christ, who was yet to come in the flesh, “Thou art a priest for ever after the order of Melchizedek,” . . . (City of God, Book XVI, 22; NPNF 1, Vol. II)

Not only is no one forbidden to take as food the Blood of this Sacrifice, rather, all who wish to possess life are exhorted to drink thereof. (Questions of the Hepateuch, 3, 57; in Jurgens, ibid., Vol. III, 1979, 134)

The entire Church observes the tradition delivered to us by the Fathers, namely, that for those who have died in the fellowship of the Body and Blood of Christ, prayer should be offered when they are commemorated at the actual Sacrifice in its proper place, and that we should call to mind that for them, too, that Sacrifice is offered. (Sermo, 172, 2; 173, 1; De Cura pro mortuis, 6; De Anima et ejus Origine, 2, 21; in Hugh Pope, St. Augustine of Hippo, Garden City, New York: Doubleday Image, 1961 [originally 1937], 69)

The Sacrifice of our times is the Body and Blood of the Priest Himself . . . Recognize then in the Bread what hung upon the tree; in the chalice what flowed from His side. (Sermo iii. 1-2; in Pope, ibid., 62)

Out of hatred of Christ the crowd there shed Cyprian’s blood, but today a reverential multitude gathers to drink the Blood of Christ . . . this altar . . . whereon a Sacrifice is offered to God . . . (Sermo 310, 2; in Pope, ibid., 65)

[F]or it is to God that sacrifices are offered . . . But he who knows the one sacrifice of Christians, which is the sacrifice offered in those places, also knows that these are not sacrifices offered to the martyrs . . . For we do not ordain priests and offer sacrifices to our martyrs, as they do to their dead men, for that would be incongruous, undue, and unlawful, such being due only to God . . . (City of God, Book VIII, chapter 27; NPNF 1, Vol. II)

Was not Christ once for all offered up in His own person as a sacrifice? and yet, is He not likewise offered up in the sacrament as a sacrifice, not only in the special solemnities of Easter, but also daily among our congregations; so that the man who, being questioned, answers that He is offered as a sacrifice in that ordinance, declares what is strictly true? For if sacraments had not some points of real resemblance to the things of which they are the sacraments, they would not be sacraments at all. (Epistles, 98, 9; NPNF 1, Vol. I)

The animal sacrifices, therefore, presumptuously claimed by devils, were an imitation of the true sacrifice which is due only to the one true God, and which Christ alone offered on His altar. . . . This sacrifice is also commemorated by Christians, in the sacred offering and participation of the body and blood of Christ. (Against Faustus, XX, 18; NPNF 1, Vol. IV)

St. Cyril of Alexandria

He states demonstratively: “This is My Body,” and “This is My Blood“(Mt. 26:26-28) “lest you might suppose the things that are seen as a figure. Rather, by some secret of the all-powerful God the things seen are transformed into the Body and Blood of Christ, truly offered in a sacrifice in which we, as participants, receive the life-giving and sanctifying power of Christ. (Commentary on Matthew [Mt. 26:27]; in Jurgens, ibid., Vol. III, 220)

St. Gregory the Great

If guilty deeds are not beyond absolution even after death, the sacred offering of the saving Victim consistently aids souls even after death . . . (Dialogues 4, 55; in Jaroslav Pelikan, The Christian Tradition: A History of the Development of Doctrine: Vol. 1 of 5: The Emergence of the Catholic Tradition (100-600), Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1971, 356)

* * *Protestant Church historian Philip Schaff:

The Catholic church, both Greek and Latin, sees in the Eucharist not only a sacramentum, in which God communicates a grace to believers, but at the same time, and in fact mainly, a sacrificium, in which believers really offer to God that which is represented by the sensible elements. For this view also the church fathers laid the foundation, and it must be conceded they stand in general far more on the Greek and Roman Catholic than on the Protestant side of this question.

. . . In this view certainly, in a deep symbolical and ethical sense, Christ is offered to God the Father in every believing prayer, and above all in the holy Supper; i.e. as the sole ground of our reconciliation and acceptance . . .

But this idea in process of time became adulterated with foreign elements, and transformed into the Graeco-Roman doctrine of the sacrifice of the mass. According to this doctrine the Eucharist is an unbloody repetition of the atoning sacrifice of Christ by the priesthood for the salvation of the living and the dead; so that the body of Christ is truly and literally offered every day and every hour, and upon innumerable altars at the same time. The term mass, which properly denoted the dismissal of the congregation (missio, dismissio) at the close of the general public worship, became, after the end of the fourth century, the name for the worship of the faithful, which consisted in the celebration of the eucharistic sacrifice and the communion.

. . . We pass now to the more particular history. The ante-Nicene fathers uniformly conceived the Eucharist as a thank-offering of the church; the congregation offering the consecrated elements of bread and wine, and in them itself, to God. This view is in itself perfectly innocent, but readily leads to the doctrine of the sacrifice of the mass, as soon as the elements become identified with the body and blood of Christ, and the presence of the body comes to be materialistically taken. The germs of the Roman doctrine appear in Cyprian about the middle of the third century, in connection with his high-churchly doctrine of the clerical priesthood. Sacerdotium and sacrificium are with him correlative ideas.

. . . The doctrine of the sacrifice of the mass is much further developed in the Nicene and post-Nicene fathers, though amidst many obscurities and rhetorical extravagances, and with much wavering between symbolical and grossly realistic conceptions, until in all essential points it is brought to its settlement by Gregory the Great at the close of the sixth century.

. . . 2. It is not a new sacrifice added to that of the cross, but a daily, unbloody repetition and perpetual application of that one only sacrifice. Augustine represents it, on the one hand, as a sacramentum memoriae, a symbolical commemoration of the sacrificial death of Christ; to which of course there is no objection. But, on the other hand, he calls the celebration of the communionverissimum sacrificium of the body of Christ. The church, he says, offers (immolat) to God the sacrifice of thanks in the body of Christ, from the days of the apostles through the sure succession of the bishops down to our time. But the church at the same time offers, with Christ, herself, as the body of Christ, to God. As all are one body, so also all are together the same sacrifice. According to Chrysostom the same Christ, and the whole Christ, is everywhere offered. It is not a different sacrifice from that which the High Priest formerly offered, but we offer always the same sacrifice, or rather, we perform a memorial of this sacrifice. This last clause would decidedly favor a symbolical conception, if Chrysostom in other places had not used such strong expressions as this: “When thou seest the Lord slain, and lying there, and the priest standing at the sacrifice,” or: “Christ lies slain upon the altar.”

3. The sacrifice is the anti-type of the Mosaic sacrifice, and is related to it as substance to typical shadows. It is also especially foreshadowed by Melchizedek’s unbloody offering of bread and wine. The sacrifice of Melchizedek is therefore made of great account by Hilary, Jerome Augustine, Chrysostom, and other church fathers, on the strength of the well-known parallel in the seventh chapter of the Epistle to the Hebrews.

. . . Cyril of Jerusalem, in his fifth and last mystagogic Catechesis, which is devoted to the consideration of the eucharistic sacrifice and the liturgical service of God, gives the following description of the eucharistic intercessions for the departed:

“When the spiritual sacrifice, the unbloody service of God, is performed, we pray to God over this atoning sacrifice for the universal peace of the church, for the welfare of the world, for the emperor, for soldiers and prisoners, for the sick and afflicted, for all the poor and needy. Then we commemorate also those who sleep, the patriarchs, prophets, apostles, martyrs, that God through their prayers and their intercessions may receive our prayer; and in general we pray for all who have gone from us, since we believe that it is of the greatest help to those souls for whom the prayer is offered, while the holy sacrifice, exciting a holy awe, lies before us.”

This is clearly an approach to the later idea of purgatory in the Latin church. Even St. Augustine, with Tertullian, teaches plainly, as an old tradition, that the eucharistic sacrifice, the intercessions or suffragia and alms, of the living are of benefit to the departed believers, so that the Lord deals more mercifully with them than their sins deserve.

(History of the Christian Church, Vol. III: Nicene and Post-Nicene Christianity: A.D. 311-600, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1974, from the revised fifth edition of 1910; §96. “The Sacrifice of the Eucharist,” 503-508, 510)

The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church:

It was also widely held from the first that the Eucharist is in some sense a sacrifice, though here again definition was gradual. The suggestion of sacrifice is contained in much of the NT language . . . the words of institution, ‘covenant,’ ‘memorial,’ ‘poured out,’ all have sacrificial associations. In early post-NT times the constant repudiation of carnal sacrifice and emphasis on life and prayer at Christian worship did not hinder the Eucharist from being described as a sacrifice from the first . . .

From early times the Eucharistic offering was called a sacrifice in virtue of its immediate relation to the sacrifice of Christ. (F. L. Cross and E. A. Livingstone, editors; 2nd edition, Oxford University Press, 1983, 476, 1221)

Protestant historian J. N. D. Kelly:

[T]he Eucharist was regarded as the distinctively Christian sacrifice from the closing decade of the first century, if not earlier. Malachi’s prediction (1:10 f.) that the Lord would reject the Jewish sacrifices and instead would have ‘a pure offering’ made to Him by the Gentiles in every place was early seized [did. 14,3; Justin, dial. 41,2 f.; Irenaeus, haer. 4,17,5] upon by Christians as a prophecy of the eucharist.

The Didache indeed actually applies [14, 1] the term thusia, or sacrifice, to the eucharist, and the idea is presupposed by Clement in the parallel he discovers [40-4] between the Church’s ministers and the Old Testament priests and levites . . . Ignatius’s reference [Philad. 4] to ‘one altar, just as there is one bishop’, reveals that he, too thought in sacrificial terms. Justin speaks [Dial. 117,1] of ‘all the sacrifices in this name which Jesus appointed to be performed, viz. in ther eucharist of the bread and the cup, and which are celebrated in every place by Christians’. Not only here but elsewhere [Ib. 41,3] too, he identifies ‘the bread of the eucharist, and the cup likewise of the eucharist’, with the sacrifice foretold by Malachi. For Irenaeus [Haer. 4,17,5] the eucharist is ‘the new oblation of the new covenant’, . . .

It was natural for early Christians to think of the eucharist as a sacrifice. The fulfillment of prophecy demanded a solemn Christian offering, and the rite itself was wrapped in the sacrificial atmosphere with which our Lord invested the Last Supper. The words of institution, ‘Do this’ (touto poieite), must have been charged with sacrificial overtones for second-century ears; Justin at any rate understood [1 apol. 66,3; cf. dial. 41,1] them to mean, ‘Offer this.’ . . . Justin . . . makes it plain [Dial. 41,3] that the bread and the wine themselves were the ‘pure offering’ foretold by Malachi . . . he uses [1 apol. 65,3-5] the term ‘thanksgiving’ as technically equivalent to ‘the eucharistized bread and wine’. The bread and wine, moreover, are offered ‘for a memorial (eis anamnasin) of the passion,’ a phrase which in view of his identification of them with the Lord’s body and blood implies much more than an act of purely spiritual recollection. Altogether it would seem that, while his language is not fully explicit, Justin is feeling his way to the conception of the eucharist as the offering of the Saviour’s passion. (Early Christian Doctrines, San Francisco: Harper & Row, fifth revised edition, 1978, 196-197)

[T]he eucharist was regarded without question as the Christian sacrifice. (Ibid., 449)