(2-9-08)

***

Just when I think that I’ve discovered pretty much all of Martin Luther’s many false beliefs, and that there couldn’t possibly be any more, lo and behold, here comes another one out of nowhere. Today I came across someone mentioning English Protestant William Tyndale’s acceptance of “conditional immortality” (a sort of synonym for, or notion associated with, soul sleep, or psychopannychia).

Curious, I started Googling, and soon found that Martin Luther also espoused this false doctrine, in overreaction to supposed excessive “Greek philosophical / Platonic / Aristotelian,” etc. influence on Catholic Christianity (in this instance, on its eschatology, or “psychology”: i.e., doctrine of the soul).

Catholics, on the other hand (and post-Luther Lutherans, as we shall see, and most Protestants), believe that the soul of man is conscious at all times, either in Sheol / Hades, purgatory, heaven, or hell, and never ceases being conscious. Nor is this only a “Catholic thing.” It’s a biblical thing (which is precisely why the vast majority of Christians have believed it). Hence, John Calvin soundly refuted the contrary error from Scripture, in 1536. Luther wrote in 1542:

But we Christians, who have been redeemed from all this through the precious blood of God’s Son, should train and accustom ourselves in faith to despise death and regard it as a deep, strong sweet sleep; to consider the coffin as nothing other than our Lord Jesus’ bosom or Paradise, the grave as nothing other than a soft couch of ease or rest. As verily, before God, it truly is just this; for he testifies, John 11:11: Lazarus, our friend sleeps; Matthew 9:24: The maiden is not dead, she sleeps. Thus too, St. Paul in 1 Corinthians 15, removes from sight all hateful aspects of death as related to our mortal body and brings forward nothing but charming and joyful aspects of the promised life. He says there [vv.42ff]: It is sown in corruption and will rise in incorruption; it is sown in dishonor (that is, a hateful, shameful form) and will rise in glory; it is sown in weakness and will rise in strength; it is sown in natural body and will rise a spiritual body. (Christian Songs Latin and German, For Use at Funerals, from: Works of Martin Luther, Philadelphia: Muhlenberg Press, 1932, Vol. 6, 287-288)

Based on the premise of this unscriptural denial (abominated even by fellow “reformer” John Calvin), he goes on in the very next paragraph to blast purgatory, prayers for the dead, etc. (note the important, revealing connecting word “accordingly”):

Accordingly we have driven the pestilential abominations from our churches, such as vigils, masses for the dead, processions, purgatory, and all other mockery and hocus pocus on behalf of the dead. We have abolished all these and have cleaned them out thoroughly and do not want our churches to be houses of wailing and places of mourning any longer . . . Nor do we sing any funereal hymns or doleful songs over our dead and at the graves, but comforting hymns, of the forgiveness of sins, of rest, of sleep, of life, and of the resurrection of Christians who have died . . .

Luther alludes to this causal connection on the next page (p. 289), referring to “purgatory with its torment and satisfaction, on account of which their dead can neither sleep nor rest.” If men are only conscious after being resurrected to eternal life in heaven, they would be in no need of our prayers. Purgatory is impossible without immaterial conscious souls. Luther denied one necessary premise of purgatory; therefore, purgatory goes along with it. Nor can souls be prayed for if there is no conscious state other than heaven or hell, because those in hell are beyond prayer and those in heaven have no need of it whatsoever.

Others have noted the relationship between Luther’s erroneous soul sleep affinities and his rejection of purgatory. For example, Bruce A. Demarest and Gordon Russell Lewis, in their book, Integrative Theology (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan, 1994, three-volumes-in-one edition), state on Vol. III, p. 451:

Reacting to the Roman doctrine of purgatory, Luther on occasion described the intermediate state as a kind of sleep. At death the believer sleeps in the grave awaiting the Last Judgment rather than enduring purgatory . . . in that state the soul is less than fully conscious . . . Luther was not dogmatic on this issue, and in later writings he appears to have softened this position.

Likewise, Lutheran Luther scholar Julius Köstlin comments (my emphases in blue):

The scriptural mode of referring to “the sleep of the dead” inclined him to adopt the theory of a sleep of the soul, in which it shall not know where it is until the Day of Judgment. This, he acknowledges in 1522 to Amsdorf, who asked him for his opinion on the subject. . . . he did not venture to regard such a state of sleep as universal. It merely appears probable to him that the majority of the dead are in such a state. The inclination to this view must also have helped to undermine for Luther the very foundations of the theory of purgatory. Thus, he writes in the letter to Amsdorf, that purgatory is for him not a place, but an inner condition, namely, a foretaste of hell in this present life, such as Jesus, David, Job and many others experienced (in this world). . . . As opposed to the theory, that all souls tarrying between heaven and earth are in purgatory, he again points to the sleep which may be their condition. (The Theology of Luther: In Its Historical Development and Inner Harmony, Philadelphia: Lutheran Publication Society, 1897, Vol. I, p. 471)

The aforementioned letter to Nicholas Amsdorf was dated 13 January 1522. Here is a portion, from another Protestant biography of Luther (my emphasis):

As to purgatory, I think it a very uncertain thing. It is probable, in my opinion, that, with very few exceptions indeed, the dead sleep in utter insensibility till the day of judgment. (The Life of Luther, Jules Michelet; translated by William Hazlitt, London: H.G. Bohn, second edition, 1862, p. 133)

So in one fell swoop, Luther eliminates purgatory and prayer for the dead, based on a denial (with some exceptions) of the consciousness of the soul after death, itself based on fallacious and shoddy biblical exegesis and false equation of biblical Christianity with pagan Greek philosophy. This would follow logically, even if Luther had not expressly connected the two things in his own words, but since he himself has made the association, we know that he was aware of his own rationale (at least in part) for ditching these previous Christian beliefs. Luther may be a bit unsure about soul sleep, but he is flat-out certain that purgatory and prayers for the dead are abominations, based on his unsure opinion on soul sleep.

Luther scholar Paul Althaus himself exhibits a thorough anti-traditional doctrinal attitude when he describes Catholic eschatology and doctrine of the soul as follows:

Thus the original biblical concepts have been replaced by ideas from Hellenistic gnostic dualism. The New Testament idea of the resurrection which affects the total man has had to give way to the immortality of the soul . . . Against this background, we can measure the significance of Luther’s Reformation for eschatology. (The Theology of Martin Luther, translated by Robert C. Schultz, Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1966, 414)

That said, he presents what he believes to be Luther’s position on this matter:

Luther generally understands the condition between death and the resurrection as a deep and dreamless sleep without consciousness and feeling. (Ibid., 414)

Althaus helpfully informs his readers that confessional Lutheranism didn’t even agree with Luther in this area of thought:

Later Lutheran Church theology did not follow Luther on this point. Rather, it once again adopted the medieval tradition and continued it. Before the resurrection, souls live in a blessed condition with Christ even though they are without bodies. . . . The dualistic understanding of the soul conquered once again. (Ibid., 417)

Of course, Luther wouldn’t be Luther if he didn’t contradict himself, or waffle, or vacillate, or condemn someone else for believing what he himself believes in his weaker moments, or on odd-numbered days in June in leap years, or when the moon is full in autumn. There are some indications that he qualified or changed his beliefs expressed above. I cite again the letter to Nicholas von Amsdorf (13 January 1522). Luther cautiously responded to the question of what happens to the soul after death:

Concerning your “souls,” I have not enough [insight into the problem] to answer you. I am inclined to agree with your opinion that the souls of the just are asleep and that they do not know where they are up to the Day of Judgment. I am drawn to this opinion by the word of Scripture, “They sleep with their fathers.” The dead who were raised by Christ and by the apostles testify to this fact, since they were as if they had just awakened from sleep and didn’t know where they had been. To this must be added the ecstatic experiences of many saints. I have nothing with which I could overthrow this opinion. But I do not dare to affirm that this is true for all souls in general, because of the ecstasy of Paul, and the ascension of Elijah and of Moses (who certainly did not appear as phantoms on Mount Tabor).

Who knows how God deals with the departed souls? Can’t [God] just as well make them sleep on and off (or for as long as he wishes [them to sleep]), just as he overcomes with sleep those who live in the flesh? And again, that passage in Luke 16 [:23 ff.] concerning Abraham and Lazarus, although it does not force the assumption of a universal [capacity of feeling on the part of the departed], yet it attributes a capacity of feeling to Abraham and Lazarus, and it is hard to twist this passage to refer to the Day of Judgment.

I think the same about the condemned souls; some may feel punishments immediately after death, but others may be spared from [punishments] until that Day [of Judgment]. For the reveler [in that parable] confesses that he is tortured; and the Psalm says, “Evil will catch up with the unjust man when he perishes.” You perhaps also refer this either to the Day of Judgment or to the passing anguish of physical death. Then my opinion would be that this is uncertain. It is most probable, however, that with few exceptions, all [departed souls] sleep without possessing any capacity of feeling. Consider now who the “spirits in prison” were to whom Christ preached, as Peter writes: Could they not also sleep until the Day [of Judgment]? Yet when Jude says concerning the Sodomites that they suffer the pain of eternal fire, he is speaking of a present [fire]. (Luther’s Works, Vol. 48, 360-361)

Paul Althaus elaborates:

Some Bible passages do compel Luther to make certain exceptions to the rule that the dead sleep. God can also awaken them for a time- just as he allows those of us here upon the earth to alternate between waking and sleeping. And the fact that they are asleep does not hinder souls from experiencing visions and from hearing God and the angels speak. (Althaus, ibid., 415; from WA 43; 360; cf. LW 4, 313)

More ambiguous Luther statements:

We do not have to know how the soul rests. It is certain that it is alive. (Lectures on Genesis; written between 1539-1541; LW 5:74)

But now another question arises. Since it is certain that the souls are living and are in peace, what kind of life or rest is this? But this question is too lofty and too difficult for us to be able to define it. For God did not want us to know this in this life. Thus it is enough for us to know that souls do not go out of their bodies into the danger of tortures and punishments of hell, but that there is ready for them a chamber in which they may sleep in peace. Nevertheless, there is a difference between the sleep or rest of this life and that of the future life. For toward night a person who has become exhausted by his daily labor in this life enters into his chamber in peace, as it were, to sleep there; and during this night he enjoys rest and has no knowledge whatever of any evil caused either by fire or by murder. But the soul does not sleep in the same manner. It is awake. It experiences visions and the discourses of the angels and of God. Therefore the sleep in the future life is deeper than it is in this life. Nevertheless, the soul lives before God. With this analogy, which I have from the sleep of a living person, I am satisfied; for in him there is peace and quiet. He thinks that he has slept barely one or two hours, and yet he sees that the soul sleeps in such a manner that it also is awake. (Lectures on Genesis; written between 1539-1541; LW 4:313)

Luther’s opinion is somewhat unsure and shifting; hence undogmatic. But I will again contend that Luther is not unsure at all about what he has rejected from unbroken Christian tradition: purgatory, prayers for the dead, etc. In the same work cited immediately above, for example, he wrote:

I have said this [i.e., preceding material about the conscious or unconscious state of the dead] in order to curb unprofitable and idle thoughts about these questions . . .

But here one must also censure the foolishness of the papists, who have devised five places after death: . . . (3) purgatory; (4) the limbo of the fathers (in the New Testament they added Paradise on account of Christ’s statement in Luke 23:43: “Today you will be with Me in Paradise”) . . .

The third sphere is that of purgatory . . . From this source comes the hogwash of indulgences and the entire papistic religion.

The fourth place is the limbo of the fathers. They say that Christ descended to this place, broke it open, and set free — not from hell but from limbo — the fathers who were troubled by the longing and waiting for Christ but were not enduring punishments or torments.

With these silly ideas the papists have filled the Church and the world. (Lectures on Genesis; written between 1539-1541; LW 4:314-315)

Luther ridiculously argues that the “Paradise” referred to by Jesus in Luke 23:43 is heaven. The only problem with this is that Jesus didn’t go to heaven on the day he died (“today”). He ascended to heaven two days later. So where was He and the dead criminal on the day of their deaths? The limbo of the fathers fits the bill perfectly. As Luke 16 indicates, it was divided into two sections: for the good and the wicked. Jesus went to deliver the saved elect, as many Christians (not just Catholics) believe is referred to in Ephesians 4:8-10 and 1 Peter 3:19-20.

So we see Luther mocking and ridiculing not just purgatory, but also the biblical belief in the limbo of the fathers (synonymous with Sheol or Hades), over against massive biblical indication. And what would he propose as a substitute for the traditional eschatological doctrine? Luther would have it that our Lord Jesus Christ literally descended into hell to be tormented by Satan (which is not only ludicrous, but blasphemous):

Christ suffers hell and the wrath of God and overcomes them with the power of his love of God. This is how Luther understands the Article of Christ’s descent into hell. It is part of Christ’s death agony. Through it Christ gains the victory over hell . . . Luther also teaches a descent of Christ into hell after his death. This two-sidedness brings him into difficulty. . . .

Luther’s doctrine of the cross transcends all earlier theology through the radical seriousness with which he allows Christ to suffer both hell and being totally forsaken by God . . . He who wills to be our Savior must also have suffered our own hell. This hell is not a future condition or place but a present reality which a terrified conscience experiences under the wrath of God. Christ who has experienced both hell and being forsaken by God is directly involved in the distress of all men under the wrath of God and their distress is directly involved in his passion. (Althaus, ibid., 207-208; the author says in footnote 32 on p. 208 that his “main source” for this strain of Luther’s thought is “the large commentary on Galatians, from LW, vol. 26, 276 ff. [commentary on Gal 3:13], and Luther’s sermons)

Such a view is its own refutation. Suffice it for us to point out the particular absurdity (one of many here) of what this does to Luther’s claim that “Paradise” refers to heaven. So what did Jesus do after He died? First he went to heaven (“Paradise”) with the thief next to Him, so as to fulfill that promise, then down to hell to be tormented by Satan as if He Himself were damned, so He could experience the full measure of fallen humanity?

Or vice versa? He went to hell first, then heaven, then came back down and ascended to heaven again? He wins the victory over death and sin on the cross and then goes to hell so he can “really” win it by defeating the devil’s wicked and evil designs in person (as if the agony of the cross were not enough)? There is no end of incoherent silliness in this view of Luther’s. The traditional Catholic view makes far more biblical and logical sense.

Here is documentation of William Tyndale’s heretical belief:

And ye, in putting them [the departed souls] in heaven, hell, and purgatory, destroy the arguments wherewith Christ and Paul prove the resurrection . . . The true faith putteth [setteth forth] the resurrection, which we be warned to look for every hour. The heathen philosophers, denying that, did put [set forth] that the souls did ever live. And the pope joineth the spiritual doctrine of Christ and the fleshly doctrine of philosophers together; things so contrary that they cannot agree, no more than the Spirit and the flesh do in a Christian man. And because the fleshly-minded pope consenteth unto heathen doctrine, therefore he corrupteth the Scripture to stablish it. (An Answer to Sir Thomas More’s Dialogue [Parker’s 1850 reprint], bk. 4, ch. 4, pp. 180-181)

On p. 118 of the same work, Tyndale writes:

And I marvel that Paul had not comforted the Thessalonians with that doctrine, if he had wist [known] it, that the souls of their dead had been in joy . . .

***

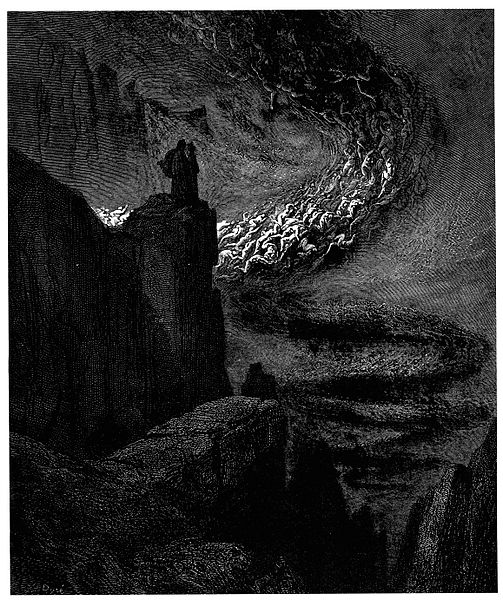

Photo credit: Illustration to Dante’s Inferno. Plate XIV: Canto V: “The infernal hurricane that never rests / Hurtles the spirits onwards in its rapine” (1857), by Gustave Doré (1832-1883) [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

***