***

(5-13-06)

***

This is a collection of follow-up discussion and my additional comments, with regard to my earlier summary-post, Galileo: The Myths and the Facts. Eric is a fellow Catholic. His words will be in green. The words of the philosopher-scientist Thomas Kuhn will be in blue.

“DelRay”, a Catholic, wrote:

I’m concerned that you weaken, rather than strengthen, your argument by bringing in Luther, Zwingli, Melanchton, et.al. Few thoughtful Protestants attribute any kind of infallibility to them. Remember that the point under discussion is not geocentrism, but infallibility.

Sure, but I still think it is relevant, even if off the technically main point. Infallibility is probably the main target of those who wish to make hay out of the Galileo case. I did it myself before I converted.

But we must remember that there is also the charge that the Church is anti-science, which was a strong sub-theme of my paper; not only anti-science, but particularly so over against the Protestants. It’s the old double standard again: our isolated, atypical mistake is trumpeted, exaggerated and even presented inaccurately, while the Protestants (who had a far worse record regarding science) get a pass. For the sake of historical accuracy this needs to be pointed out, because Protestants will attempt to use Galileo as a club to supposedly show their better record, just as scientists and secularists and atheists use it to show that religion is fundamentally opposed to science.

In that sense, it is highly important to include that material. It’s the historical record. No one in their right mind (who is familiar with the facts) would accuse either Protestants or Catholics today of being anti-science (except for the small group of young earth creationists).

I present these things for much the same reason that I wrote my paper, The Protestant Inquisition; precisely because no one ever hears about that, and it is casually assumed that the early Protestants were brave, noble champions of freedom of religion. Nothing could be further from the truth. I would contend that their record of intolerance was worse than the Catholic one, and also more internally-inconsistent.

* * *

Galileo was overconfident in proclaiming his theory as fact, which is ironic, since the Church gets excoriated for doing the same thing from its perspective. Both sides were overly-dogmatic; a little less on each side and this thing wouldn’t even be known today; or so it seems to me.

* * *

I think your post would be more effective if you took the time to document the various claims, for instance the dates his works were allowed to be published, and then taken off the Forbidden Index, as well as the various ideas and quotations you cite in the second paragraph.

As it stands, it is right from my upcoming book: The One-Minute Apologist, the first draft of which will be finished this very day. I was allowed about 700 words or two pages for each section, so it was very difficult getting everything that I thought needed to be included in the space I had. But I am adding more relevant (and I think, interesting and informative) information in the present post.

Have you ever taken the time to actually read the decrees of the Church condemning Galileo? . . . It seems to me that there’s more that was condemned than a simple forbidding of talking about the matter. Even holding heliocentrism as a private belief was considered heretical!

I looked over some of them. I don’t think they can be defended at all. It was a huge mistake. That being the case, an apologist like myself can only make arguments that it didn’t affect infallibility and that there were factors of excessive dogmatism on both sides, etc.

My main concern is infallibility and to counter the notion that this somehow proves that the entire Church is hostile to scientific inquiry. It is not, and this is quite clear, the more one studies the matter. For heaven’s sake, science certainly has its skeletons in the closet that we rarely hear about, too, such as widespread support for the racist pseudo-science of phrenology in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Also, one could cite eugenics, the Nazi scientific enterprises of experimentation on concentration camp inmates (after all, Germany was a highly scientifically-advanced nation), so-called Nebraska Man, presented as compelling evidence for human evolution at the Scopes Trial in 1925: a single tooth which turned out to be that of an extinct pig; Piltdown Man, which was revealed as a (rather obvious) hoax in 1954 (after 42 years of being widely accepted and triumphalistically proclaimed as “evidence”), etc.

How much does one hear about all of that? I’m sure there is much more folly to be found, too (e.g., it was standard belief for a long time that the universe was eternal, whereas we now know that is false, and Christians had always known it from revelation).

And these were theories or “facts” touted by science proper. So the Church (i.e., one of its tribunals) made a mistake (one not affecting its doctrine of infallibility); many prominent scientists and scientific institutions have made plenty of stupid mistakes too. I am all about showing the entire historical record, which is invariably far more complex and interesting than the propaganda we largely get fed in schools and in popular secularist thinking.

This post still leaves the Church with a dilemma. Constantly, we Catholics are told that we have to give internal assent and external obedience to all decisions of the Church, even non-infallible ones. Anytime a Catholic questions, for example, monogenism or the Church’s condemnations of millenialism, they are considered heretics or dissenters, although the Church has not declared anything infallible on these matters.

Which is to say: If the Church was wrong on Galileo, why should we believe her on anything else she teaches noninfallibly? Why should I believe her on monogenism, for instance?

Monogenism (the common origin of all mankind) has far more to do with theology than with science, so therefore it is within the Church’s purview of faith and morals. Its main component is the belief that man has a soul, supernaturally infused by God. This cannot be proven by science; it would be like trying to prove that Jesus was the God-Man by physically examining Him. It can’t be done, because it is a non-material question which science cannot treat, by definition. Likewise, this is true regarding “proof” that man has a soul. I would contend that this is infallible teaching.

Millenarianism (a literal 1000-year kingdom of Christ on earth prior to the 2nd Coming) is a little trickier. The Catechism does casually reject it (#676) and a decree was made by the Holy Office on 21 July 1944 (Denzinger 2296). The Catechism also mentions Denzinger 3839 from the 1965 edition (which is more recent than my 1955 version). That seems to be sufficient in the ordinary magisterium, though I am no expert in this area and simply give my opinion as a lay apologist.

In any event, it requires faith to believe that the Church speaks authoritatively and can be trusted for its theological judgments (neither of these two matters being primarily scientific ones). You’ll never be able to prove that in an “airtight” sense. I’m quite untroubled and satisfied myself as to the validity and solidity of my Catholic faith. In fact, the more apologetics I do, the more strong my faith becomes, because the cumulative “case” is so compelling and so superior to any alternative I have seen.

As well, why wouldn’t geocentrism be considered a one-time doctrine of the Church’s ordinary magisterium?

Because it was never taught or defined by the magisterium. This is the whole point. That’s why my friend Patrick Madrid, in his book Pope Fiction, in the section on Galileo, challenges anyone to produce the name of a pope and date and name of a document where this was supposedly done (p. 179). You are welcome to do so yourself. The pope during the Galileo trial of 1633 didn’t even sign the document condemning heliocentrism.

If Galileo had denied this cosmology, he would have been tortured, burned at the stake, and denied burial in consecrated ground.

Hardly. Folks knew that he already denied it. He simply lied, saying he didn’t hold it. Apparently it was a sort of game for many, such as Republican Supreme Court nominees saying what the liberal Democrats need to hear, and being “minimalistic” in their replies, so that they can be confirmed. This was a “monkey trial” or a kind of “circus”, just as those proceedings in the Senate are these days. So I say that most people who knew anything knew that he was a heliocentrist, yet he wasn’t burned or tortured, and wasn’t denied a burial in consecrated ground.

I’d say this is indication that the Church wanted this to be held definitively by the faithful!

From what I have seen, some people in high places (including the pope of that time) thought it should be held, but it was not decreed on any sort of magisterial level, let alone infallible. So this is a non-issue.

* * *

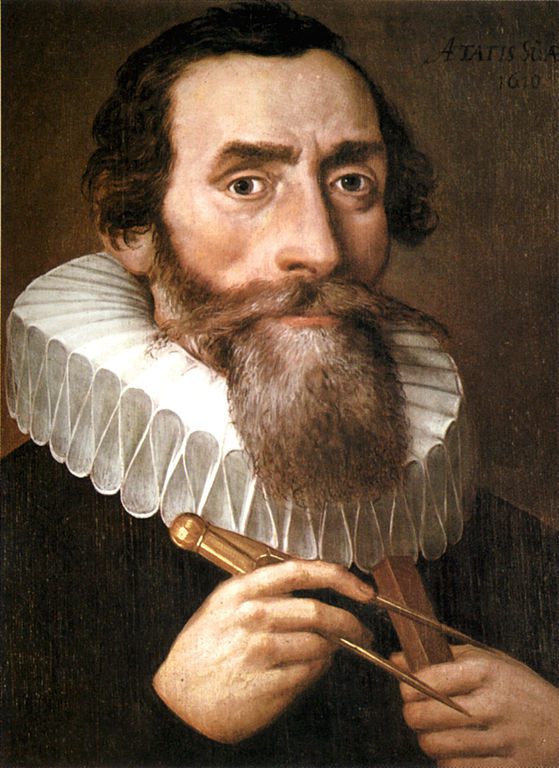

This was a difficult section to write in the space that I had, so I wanted to do the very best I could to do the subject justice and give the best Catholic “case” that could be given in a nutshell. As it turned out, I found out that Frederick Copleston (the famous Catholic historian of philosophy) and Thomas Kuhn (author of The Copernican Revolution and the well-known, influential Structure of Scientific Revolutions) both maintained that St. Robert (Cardinal) Bellarmine had a more realistic view of the epistemological strength of a scientific hypothesis than Galileo. Galileo was dogmatically proclaiming that his theory was a fact. We know beyond a doubt that important aspects of it were dead wrong.

Thomas Kuhn, in his book, The Copernican Revolution, after commenting on some folks who refused to look through Galileo’s telescope, wrote:

“Most of Galileo’s opponents behaved more rationally. Like Bellarmine, they agreed that the phenomena were in the sky but denied that they proved Galileo’s contentions. In this, of course, they were quite right. Thought the telescope argued much, it proved nothing.”

(New York: Random House / Vintage Books, 1957, p. 226)

I also read that Thomas Henry Huxley, no champion of the Catholic Church, felt that the Church had actually made the better case, according to the level of scientific knowledge on the question of cosmology at that time.

After all, the Danish scientist Tycho Brahe (1546-1601), whom Kuhn described in the same book as “the preeminent astronomical authority” of the second half of the 16th century, who had “immense prestige” and who was greater in “technical proficiency” than even Copernicus (p. 200), never became convinced of heliocentrism.

In Tycho’s cosmology, the earth was the fixed center of the universe, and the sun and moon revolved around it, but the other planets revolved around the sun.

Kuhn praised Tycho’s “great ingenuity,” “phenomenal achievements” of naked-eye observations, improvement of instruments and calculations, “the reliability and the scope of the entire body of data that he collected,” and concluded, “Trustworthy, extensive, and up-to-date data are Brahe’s primary contribution to the solution of the problem of the planets” (pp. 200-201).

In other words, this man was an eminent scientist; the best astronomer, according to Kuhn, from 1550-1600 (only 16 or 33 years before Galileo’s inquiries), despite the earlier Copernicus, and yet he, too, rejected heliocentrism. So then, why is it considered such a scandal that the Church (whose sphere of expertise is not science) was so outrageously wrong, for merely accepting a position similar to that of the scientist Tycho? One must have a proper historico-scientific perspective.

Kuhn even claims that Tycho’s cosmology reconciled some of the factors in the Copernican system:

“The remarkable and historically significant feature of the Tychonic system is its adequacy as a compromise solution of the problems raised by the De Revolutionibus [Copernicus’ innovative and revolutionary treatise]. Since the earth is stationary and at the center, all the main arguments against Copernicus’ proposal vanish. Scripture, the laws of motion, and the absence of stellar parallax, all are reconciled by Brahe’s proposal, and this reconciliation is effected without sacrificing any of Copernicus’ major mathematical harmonies. The Tychonic system is, in fact, precisely the equivalent mathematically to Copernicus’ system. Distance determination, the apparent anomalies in the behavior of the inferior planets, these and the other new harmonies that convinced Copernicus of the earth’s motion are all preserved.

“. . . The relative motions of the planets are the same in both systems, and the harmonies are therefore preserved.”

(pp. 202-204)

Tycho was even quite influential:

“[T]he Tychonic system did not convert those few Neoplatonic astronomers, like Kepler, who had been attracted to Copernicus’ system by its great symmetry. But it did convert most technically proficient non-Copernican astronomers of the day, because it provided an escape from a widely-felt dilemma: it retained the mathematical advantages of Copernicus’ system without the physical, cosmological, and theological drawbacks. . . . The Tychonic system . . . appears to be an immediate by-product of the De Revolutionibus.”

(pp. 204-205)

“. . . geometrically, the Tychonic and Copernican systems were identical.”

(p. 205)

Tycho, in fact, introduced some innovations that went beyond Copernicus:

“Brahe’s system . . . forced his followers to abandon the crystalline spheres which, in the past, had carried the planets about their orbits . . . Copernicus himself had utilized spheres to account for the planetary motions . . . Any break with the tradition worked for the Copernicans, and the Tychonic system, for all its traditional elements, was an important break.

“Brahe’s skillful observations were even more important than his system in leading his contemporaries toward a new cosmology. They provided the essential basis for the work of Kepler, who converted Copernicus’ innovation into the first really adequate solution of the problems of the planets . . . the new data collected by Brahe suggested the necessity of another major departure from classical cosmology – they raised questions about the immutability of the heavens.”

(pp. 205-206)

Even the elliptical orbits and other crucial astronomical contributions of Johannes Kepler (1571-1630) were not immediately triumphant, as Kuhn notes:

“[N]ot until the last decades of the seventeenth century did Kepler’s Laws become the universally accepted basis for planetary computations even among the best practicing European astronomers.”

(p. 225)

Protestants were slow to adopt the new cosmology:

“[D]uring the closing decades of the [17th] century Copernican, Ptolemaic, and Tychonic astronomy were taught side by side in many prominent Protestant universities, and during the eigteenth century lectures on the last two systems were gradually dropped.”

(p. 227)