(largely vs. Dr. Norman Geisler)

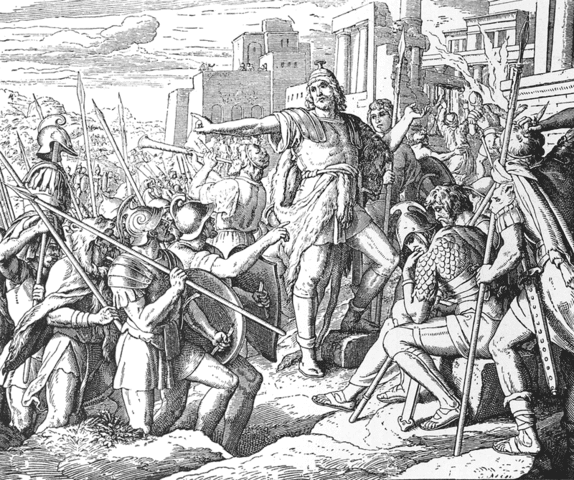

Judas Maccabeus, who led the Jewish revolt against the Seleucid Empire (167-160 B.C.), by Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld (1794-1872) [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

***

(1996)

***

An educated and committed evangelical Protestant friend (since received into the Catholic Church) wrote to me in October 1996, inquiring about arguments against the deuterocanonical books (“Apocrypha”) raised in Norman Geisler and Ralph MacKenzie’s book Roman Catholics and Evangelicals: Agreements and Differences (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Books, 1995). Her words are in blue:

* * * * *

Let me throw out some specific issues that Geisler raises . . . . 1) Item 7 regarding the councils [p.160]. a) Do the councils at Hippo and Carthage explicitly state the same deutero-canonical books that are included now?

I believe so – this is my understanding.

b) What about his claim that they were local councils and not binding on the whole church? [p.162]

That is irrelevant for at least four reasons:

1) They merely followed St. Augustine (Hippo being his See) and St. Athanasius and solidified what had already been essentially arrived at through consensus;

2) Protestants accept them (excluding the “Apocryphal” books, which is arbitrary on their part), and haven’t ever challenged the 66 books which all Christians hold in common. Why? They must believe implicitly and somewhat inconsistently (in terms of epistemology and authority questions) that God guided the men at these councils to figure out what allegedly every individual Christian with the Holy Spirit and an open mind and heart (i.e., Calvin’s view) can figure out individually (as opposed to the earliest Fathers who could not figure it out – the process taking a good 350 years!);

3) It was preceded by a Roman Council (382) of identical opinion, as you note (see below), as well as “ratification” by Popes Innocent I (405, 414) and Gelasius I (495). The 6th Council of Carthage (419) also concurred;

4) These would be binding by virtue of the ordinary Magisterium, for all Catholics, as dogma in line with true, apostolic Tradition, even though they were not technically Ecumenical Councils. But this is true for many doctrines, including the Immaculate Conception, Transubstantiation, infused justification, the infallibility of the pope, etc. Just because they were not finally, dogmatically defined in an Ecumenical Council until a later date does not mean that they were not binding parts of Tradition. The Catholic must obey – especially practically speaking – the teachings which are held firmly by the Catholic Church. There is some room and allowance for disagreement in such a situation, but it must be exercised with extreme caution and deference to the Church as “Mother” and “Guardian of the Deposit of Faith,” lest a skeptical, individualistic, and/or “anti-Traditional” attitude predominate.

Didn’t one of these councils also affirm the NT as we know it?

They all agreed on that – it being a settled issue by that time.

And didn’t one of these councils affirm some pretty standard doctrine like the trinity or something?

The Council of Rome (382) dealt with trinitarian issues. I’m not sure about the others offhand.

– see text note 13 about a). any proof about the claim that the Catholic scholars assume it [Baruch] was part of Jeremiah. [p.163]

I don’t know for sure – that would require a trip to the seminary library for me to ascertain. The relevant point is that it was included in the Canon of the Bible, wherever it was placed, a factor which is altogether secondary to the main point of discussion vis-a-vis the Canon. Baruch was Jeremiah’s secretary (Jer 36:4-32, 45:1-2), hence the connection, and I see no problem.

I find it quite amusing that Geisler picks at St. Augustine’s authoritative position on p.163, yet you can be sure that if the great Father had agreed with Geisler on this point, that fact would have been emphasized throughout the chapter (since we find this tendency frequently elsewhere in the book). This is, of course, arbitrary, and a double standard. Geisler would have us value his opinion more than that of St. Augustine?!! Isn’t that the unspoken assumption in all of this after-the-fact analysis?! And looked at from that perspective, Geisler’s enterprise is quite insubstantial and futile, in my humble opinion (not that he is consciously intending it that way). He is a prisoner of his own inadequate epistemological and ecclesiological principle. It’s either the Magisterium, or the “priesthood” of “orthodox” scholars and commentators such as Geisler, F.F. Bruce, D.A. Carson, John Gerstner, R.C. Sproul, etc. As long as the latter contradict each other, I will stick with Catholic Tradition (and for many other reasons as well). At least that is logically consistent, whether one accepts the premises or not!

– what about textnote 17 [p.163]

Assuming for the sake of argument that St. Augustine was inconsistent on this point of the “prophetic” nature of books (which is altogether possible – Fathers not being infallible), so what? This would have no bearing on conciliar and papal decisions of the Church, which alone are binding, not the individual opinions of Fathers, Doctors, or theologians, however great and brilliant. So that even if Geisler is correct on this relatively trivial point, the overall Catholic argument is not affected in the least. Dr. Geisler would have to somehow prove that Christian councils are inferior to sola Scriptura as a means of inculcating theological and moral truth to the faithful. And that would be quite a task indeed.

2) . . . the Council of Rome in 382. Geisler mentions nothing of this. Is there proof that this council affirmed all the deutero books as scriptural too?

Convenient for him to omit, isn’t it? The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (2nd ed., edited by F.L. Cross and E.A. Livingstone, Oxford Univ. Press, 1983, p.232) states:

A council probably held at Rome in 382 under St. Damasus gave a complete list of the canonical books of both the Old Testament and the New Testament (also known as the ‘Gelasian Decree’ because it was reproduced by Gelasius in 495), which is identical with the list given at Trent.

3) Geisler in his defense of the Protestant canon states that all the OT books were written by Prophets. What about Esther? My NIV says that we don’t know so how could we know that it was a Prophet? Was David considered a Prophet? – he wrote much of the Psalms.

Good point! I don’t think anyone would consider Esther a Prophet. Her book is also interesting in that it never mentions God, so that it would be difficult for an isolated individual to discover its inspired status, let alone its canonicity, every bit as much as is the case with 1 and 2 Maccabees, which are likewise histories of the Jews. I think David could be considered a Prophet, at least at times, when he gives messianic prophecies, such as Psalm 22. But It’s difficult to regard Solomon, e.g., as a Prophet, come to think of it, from what I remember of his life. And Nehemiah (an architect and administrator), and Ezra (a sort of Secretary of State in the Persian government), and whoever wrote Job and Ruth? Joshua was a Prophet? It appears that Geisler’s argument here is quite insufficient.

4) He gives some strong arguments [about alleged “propheticity” of all OT books] on page 167 – the middle and longest paragraph.

Well, they are only “strong” assuming his premise: viz., that a book must be “prophetic” to be part of the Canon. But I think that view is fatally injured by the above arguments, which are simple enough to arrive at. Geisler’s arguments are inconsistent and arbitrarily applied. He rails against the Catholic view, wherever it differs, all the while ignoring the huge deficiencies and even often self-defeating nature of the opposing Protestant claims. Geisler is a great scholar (in fact my favorite current-day Protestant apologist), but he, too, falls prey in this book to the almost ubiquitous evangelical bias against the Catholic Church. This is unfortunate. Nevertheless, I still regard his book as by far the best one written by evangelical Protestants on the subject of Catholicism. At least he believes that Catholics are Christians and does a good job in fairly presenting and explaining Catholic views.

*****

Meta Description: Brief dialogue in which I mostly reply to the objections of Protestant apologist Dr. Norman Geisler.

Meta Keywords: 46 books, 73 books, Apocrypha, apocryphal books, biblical canon, canon of Scripture, canonicity, deuterocanon, deuterocanonical books, Old Testament, septuagint, The Bible