Original title: How Protestants Can be Brethren in Christ (Christians) and [Partial] Heretics at the Same Time, According to Trent

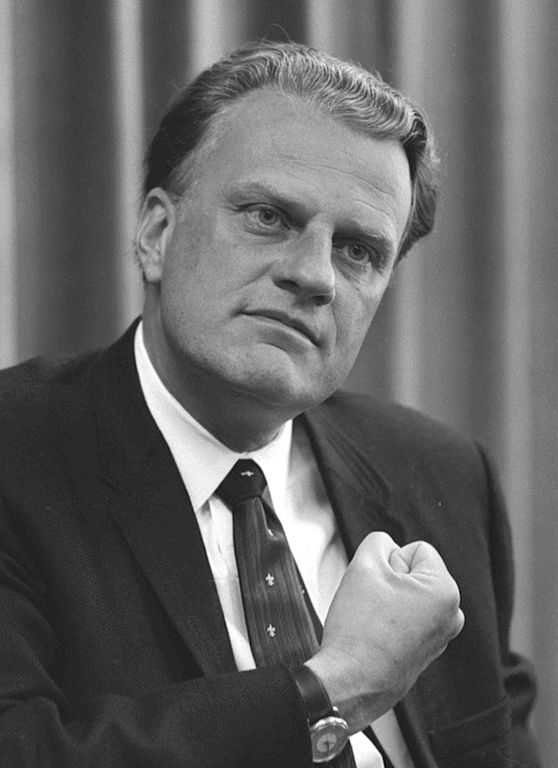

Protestant evangelist Billy Graham (1918 – ): 11 April 1966 [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

(1-4-14)

*****

There are serious heretics (like Arius, who denied the Trinity) and partial heretics (like Protestants). “Heresy” literally means “pick and choose.” But the latter can be and are called “brothers in Christ” by the Church, because of their trinitarian baptism, which incorporates them into the Church (or does that have to be defended, too?). They are Christians; in Christ.

Nor is this notion a novel thing. It goes back to the Augustine-Donatist controversy, where Augustine and the Church decided against rebaptism, and Aquinas, and Trent. Canon IV on Baptism, Council of Trent, recognizes as “true baptism” that “which is even given by heretics in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Ghost.” That ain’t modernist garbage (that many folks falsely superimpose onto the orthodox Vatican II); it’s Trent!

Thus, “heretics” (in some respects) are still brothers in Christ due (primarily, but not exclusively) to their valid baptisms, which is the entrance rite into the Church and Body of Christ. Hence, “separated brethren”: which was also in use at least as far back as Leo XIII, and wasn’t new, either.

Subjectively, current Protestants aren’t heretics, but objectively, they hold to many heretical tenets. Dr. Edwin Tait: Anglican church historian, correctly observed: “Protestantism is, by Catholic standards, heretical.”

Thus, Trent anathematizes, e.g., those who deny that baptism is necessary for salvation (Canon V on Baptism), and who deny that it regenerates, etc. Those who believe such things are heretics insofar as they are in error, in that respect. This would include many Protestants who think baptism is merely symbolic (Baptists, most pentecostals, a good number of evangelicals, Anabaptists, Mennonites, etc.).

So they are “partial heretics” in that respect and many others, from a Catholic perspective, yet still Christians because they have been validly baptized, despite their wrong interpretation of the meaning and essential nature of baptism.

Someone asked: “If I interpret this correctly, a person is a Christian merely on the acceptance of Trinitarian Baptism or belief of the dogma of the Trinity?”

He is spiritually through baptism (regeneration) and theologically by virtue of accepting essential Christian theology (agreed upon by all mainstream Christian groups), including trinitarianism.

Neither Unitarians, Mormons, nor Jehovah’s Witnesses possess valid baptism, and all deny the Trinity, so they are non-Christian on both required counts. Anyone can name the name of Jesus (even the demons do); unless it is tied to some concrete belief system, that means little in and of itself. Jesus talks about those who say “Lord, Lord” but do not follow His commands, and they are damned in the end.

There is such a thing as a valid baptism given by a heretic. Protestants remain genuine Christians, who also have various heretical elements. Protestants are Christians, according to both Trent and Vatican II. One who denies that denies both those councils. It’s as simple as that. An anti-Protestantism that would deny Christian status to our separated brethren, is anti-Trent and radically against the Mind of the Church and true ecumenism.

“Theological Christian” (i.e., doctrinally so), comes from among other things, Vatican II: Decree on Ecumenism (Unitatis Redintegratio). I’m sure the Catechism would also speak to this.

It remains true, as always, that if a Protestant truly knows that Catholicism is true and refuses to accept it, he is in danger of damnation. But the key is whether he really “knows” it or not. Only God knows all those factors. Our job is to share and defend what we know as Catholics. God takes care of grace and all the rest.

Here are some solid definitions from Fr. John A. Hardon, S. J.: Modern Catholic Dictionary:

HERESY

Commonly refers to a doctrinal belief held in opposition to the recognized standards of an established system of thought. Theologically it means an opinion at variance with the authorized teachings of any church, notably the Christian, and especially when this promotes separation from the main body of faithful believers.

In the Roman Catholic Church, heresy has a very specific meaning. Anyone who, after receiving baptism, while remaining nominally a Christian, pertinaciously denies or doubts any of the truths that must be believed with divine and Catholic faith is considered a heretic. Accordingly four elements must be verified to constitute formal heresy; previous valid baptism, which need not have been in the Catholic Church; external profession of still being a Christian, otherwise a person becomes an apostate; outright denial or positive doubt regarding a truth that the Catholic Church has actually proposed as revealed by God; and the disbelief must be morally culpable, where a nominal Christian refuses to accept what he knows is a doctrinal imperative.

Objectively, therefore, to become a heretic in the strict canonical sense and be excommunicated from the faithful, one must deny or question a truth that is taught not merely on the authority of the Church but on the word of God revealed in the Scriptures or sacred tradition. Subjectively a person must recognize his obligation to believe. If he acts in good faith, as with most persons brought up in non-Catholic surroundings, the heresy is only material and implies neither guilt nor sin against faith. (Etym. Latin haeresis, from the Greek hairesis, a taking, choice, sect, heresy.)

HERETIC

A person professing heresy. Ecclesiastical law distinguishes between a formal heretic, as one who is sinfully culpable, and a material heretic, who is not morally guilty for professing what may be objectively heretical doctrine.

APOSTASY

The total rejection by a baptized person of the Christian faith he once professed. The term is also applied in a technical sense to “apostates from religious life,” who without authorization leave a religious institute after perpetual vows with no intention of returning. (Etym. Latin apostasia, falling away or separation from God; from Greek apostasis, revolt, literally, a standing-off.)

APOSTASY IN FAITH

The complete abandonment of the Christian religion and not merely a denial of some article of the creed. Since apostolic times, it was classified among the major crimes, along with murder and adultery, whose remission in the sacrament of penance carried severe censures and, among certain rigorists, even remission of the sin was denied. St. Cyprian (d. 258), Bishop of Carthage, defended the Church’s right to remit apostasy before the hour of death, and the practice was supported by Pope Cornelius (d. 253). Under the Christian Roman Empire, apostates were punished by deprivation of civil rights, including the power to bequeath or inherit property. During the late Middle Ages, Christian who apostatized were subject to trial and punishment by the Inquisition.

The code of canon law of 1918 declared that apostates from the faith (as also heretics and schismatics) incur ipso facto excommunication, are deprived, after warning, of any benefice, dignity, pension, office, or any position they may have in the Church, and are declared under infamy. After a second warning, clerics are to be deposed, and members of a religious community automatically dismissed.

SCHISM

A willful separation from the unity of the Christian Church. Although St. Paul used the term to condemn the factions at Corinth, these were not properly schismatical, but petty cliques that favored one or another Apostle. A generation later Clement I reprobated the first authentic schism of which there is record. Paul’s exhortation to the Corinthians also gives an accurate description of the concept. “Why do we wrench and tear apart the members of Christ,” he asks, “and revolt against our own body and reach such folly as to forget that we are members of one another?” While the early Church was often plagued with heresy and schism, the exact relation between the two divisive elements was not clarified until later in the patristic age. “By false doctrines concerning God,” declared St. Augustine, “heretics wound the faith; by sinful dissensions schismatics deviate from fraternal charity, although they believe what we believe.” Heresy, therefore, by its nature refers to the mind and is opposed to religious belief, whereas schism is fundamentally volitional and offends against the union of Christian charity. (Etym. Latin schisma; from Greek skhisma, a split, division, from skhizein, to tear, rend.)

SCHISMATIC

According to Church law, a schismatic is a person who, after receiving baptism and while keeping the name of Christian, pertinaciously refuses to submit to the Supreme Pontiff or refuses to associate with those who are subject to him. The two factors, submission to the Pope and association with persons subject to him, are to be taken disjunctively. Either resisting papal authority or refusing to participate in Catholic life and worship induces schism, even without further affiliation with another religious body. Like heresy, schism is formal and culpable only when the obligations are fully realized.

CHRISTIAN

A person who is baptized. A professed Christian also believes in the essentials of the Christian faith, notably in the Apostles’ Creed. A Catholic Christian further accepts the teachings of the Roman Catholic Church, participates in the Eucharistic liturgy and sacraments of Catholic Christianity, and gives allegiance to the Catholic hierarchy and especially to the Bishop of Rome.

SEPARATED BRETHREN

All Christians who are baptized and believe in Christ but are not professed Catholics. More commonly the term is applied to Protestants.

***

***