Agreement on Ecumenism and Various Doctrines; Sola Scriptura

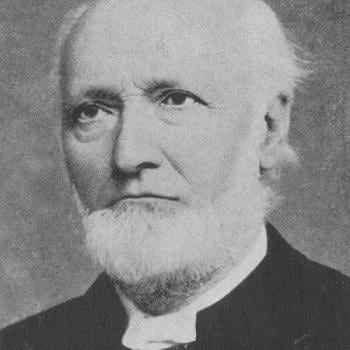

Edward Bouverie (E. B.) Pusey (1800-1882) was an English Anglican cleric, professor of Hebrew at Oxford University for more than fifty years, and author of many books. He was a leading figure in the Oxford Movement, along with St. John Henry Cardinal Newman and John Keble, an expert on patristics, and was involved in many theological and academic controversies. Pusey helped revive the doctrine of the Real Presence in the Church of England, and because of several other affinities with Catholic theology and tradition, he and his followers (derisively called “Puseyites”) were mocked by over-anxious adversaries in 1853 as “half papist and half protestant”. But, unlike Newman and like Keble, he never left Anglicanism.

This is the first of two replies to his book, An Eirenicon (New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1864), which was a letter to his former colleague and “dearest friend” William Lockhart: the first of the tractarians to convert to Catholicism (in August 1843, even before Newman’s reception in October 1845). Cardinal Newman himself replied to this book in 1865, in his volume, Certain Difficulties Felt by Anglicans in Catholic Teaching, Volume 2. I haven’t read it, so it won’t have any influence on these replies. Pusey’s words will be in blue. These two and additional replies to Pusey will be collected under the “Anglicanism” section of my Calvinism and General Protestantism web page, under his name. I use RSV for Bible citations.

*****

You know how long it has been my wish to part with all controversy, and to consecrate the evening of my life to the unfolding of some of the deep truths of God’s Holy Word, as God might enable me, by aid of those whom He has taught in times past. This employment, and practical duties which God has brought to me, were my ideal of the employments of the closing years of a laborious life. The inroad made upon the Gospel by unbelievers, or half-believers, compelled me in part to modify this my hope. Still, since there is a common foe, pressing alike upon all who believe in Jesus, I the more hoped, at least, to be freed from any necessity of controversy with any who hold the Catholic faith. The recent personal appeal of Dr. Manning to myself seems, as you and other friends think, to call for an exception to this too; . . . (p. 2)

Delightful ecumenical sentiment, in wonderful prose. I’m not enthralled with “controversy” either (it may surprise many to hear). My interest is in constructive, substantive, amiable dialogue and debate, with the aim of always seeking truth and to learn about other views, even if I disagree with them. This is as rare as hen’s teeth to find anymore (if it ever was readily obtainable). But in any event, it’s not merely controversy for its own sake, or “quarreling” or “squabbling” endlessly and aimlessly. I desire what it looks like I will find here: interaction with a well-meaning, articulate, thoughtful theological opponent, with whom I can agree in many important ways, too. It’s a well-intentioned conversation between brothers in the Christian faith.

Ever since I knew them (which was not in my earliest years) I have loved those who are called “Evangelicals.” I loved them, because they loved our Lord. I loved them, for their zeal for souls. I often thought them narrow; yet I was often drawn to individuals among them more than to others who held truths in common with myself, which the Evangelicals did not hold, at least explicitly. I believe them to be “of the truth.” I have ever believed and believe, that their faith was and is, on some points of doctrine, much truer than their words. I believed and believe, that they are often withheld from the clear and full sight of the truth by an inveterate prejudice, that that truth, as held by us, is united with error, or with indistinct acknowledgment of other truths which they themselves hold sacred. Whilst, then, I lived in society, I ever sought them out, both out of love for themselves, and because I believed that nothing (with God’s help) so dispels untrue prejudice as personal intercourse, heart to heart, with those against whom that prejudice is entertained. I sought to point out to them our common basis of faith. (p. 2)

This is another refreshing ecumenical expression, with which I very much agree, in my great affection for Protestant evangelicals, among whom I proudly counted myself between 1977 and 1990. Just as they misunderstand Pusey’s high Anglicanism, so they lack accurate knowledge — then and now — about an even “higher” Catholicism.

I have not united with them in any of those things which were not in accordance with my own principles. It was not any thing new, then, when, in high places, fundamental truths had been denied, I sought to unite with those, some of whom had often spoken against me, but against whom I had never spoken. It was the pent-up longing of years. I had long felt that common zeal for faith could alone bring together those who were opposed; I hoped that, through that common zeal and love, inveterate prejudices which hindered the reception of truth would be dispelled. This, however, was a bright vista which lay beyond. The immediate object was to resist unitedly an inroad upon our common faith. . . .

But while, on the one hand, I profess plainly that love for the Evangelicals which I ever had, I may be, perhaps, the more bound to say, that, in no matter of faith, nor in my thankfulness to God for my faith, have I changed. (p. 3)

And here he describes how often in actuality ecumenical goals and hopes die a sad death. Again, I, too, have always had the attitude he expresses: unite where possible against the enemies of Christianity. I had that view towards Catholics as a Protestant, and towards Protestants now as a Catholic. Disagreement is not the same as disrespect or malice. But of course I dispute (hopefully amiably) in areas where we hold honest disagreements. This need not be acrimonious or even not pleasurable, but we all know that all too often it descends to those things.

“I believe explicitly all which I know God to have revealed to His Church; and implicitly (implicitè) any thing, if He has revealed it, which I know not.” In

simple words, “I believe all which the Church believes.” . . . This I confess when I say to God, “I believe one Catholic and Apostolic Church.” (p. 3)

This, of course, is very un-Protestant, and an area (the rule of faith) where we have strong agreement. We disagree, however, on the nature and location of the one Church of God.

As individuals, we, too, thankfully acknowledge that whoever teaches any true faith in Jesus is, so far, one of God’s instruments against unbelief. (p. 5)

Agreed.

There is not one statement in the elaborate chapters on Justification in the Council of Trent which any of us could fail of receiving; nor is there one of their

anathemas on the subject, which in the least rejects any statement of the Church of England. (p. 8)

This is a pretty amazing statement. I can see why some (more evangelical) Anglicans would be suspicious of Pusey!

The Church of England, while teaching (as the fathers often do) that Baptism and the Holy Eucharist have a special dignity, . . . is careful not to exclude other appointments of God from being in some way sacraments, as channels of grace, or (in the old definition of sacraments), “visible signs of an invisible grace.” This is indeed inseparable from the idea of Confirmation, Orders, Absolution, Marriage.

Marriage is, we know, directly called a “Sacrament” in the Homilies. . . . “Absolution, it says, “has the promise of forgiveness of sins.” . . .

Even as to Extreme Unction, it only objects to the later abuse before the Council of Trent, when it was customarily administered to those only, of whom there was a moral certainty that they could not recover; . . . (pp. 9-10)

Blessed agreement on the sacraments as well . . .

I am persuaded that, on this point, the two Churches might be reconciled by explanation of the terms used. The Council of Trent, in laying down the doctrine of the sacrifice of the Mass, claims nothing for the Holy Eucharist but an application of the One meritorious sacrifice of the Cross. An application of that sacrifice the Church of England believes also. Many years have flowed away since we have taught this, and have noticed how the words, “sacrifice,” “proper,” or “propitiatory sacrifice,” have been alternately accepted or rejected, according as they were supposed to mean that the Eucharistic sacrifice acquired something propitiatory in itself, or only applied what was merited once and for ever by the One sacrifice of our Lord upon the Cross. (p. 12)

This is pretty amazing, too. I didn’t know this.

The chief controversy I hold to be about the sovereignty of the Pope. For this is at this time the great wall of separation which divides the two Churches. (p. 27)

It’s certainly one of the main points of dispute.

The office of our Divine Lord, as a Teacher, was, to be the perfect Revealer of the whole truth as to God, which God willed to disclose to His creatures here. This same office God the Holy Ghost undertook after the Resurrection, teaching invisibly to the Apostles that same divine truth. Our Lord said to His Apostles, “He shall teach you the whole truth, and bring all things to your remembrance, whatever I have said unto you” [Jn 14:26; 16:13]. The whole revelation then was completed at the first. (p. 37)

Of course it was. Catholics agree! It doesn’t follow, however, that all of this revelation and apostolic deposit was in the Bible or that oral tradition ceased after the writing of the New Testament.

He, “the Spirit of Truth,” was to teach the Apostles the whole truth. It was a personal promise to the Apostles, and fulfilled in them. (p. 37)

It never states in the Bible that all of this was in writing, or, for that matter, in the Bible (as determined by the Church, since it doesn’t name its own books).

The Church of this day cannot know more than St. John, else the promise would not have been fulfilled to him, that God, the Holy Ghost, should teach him the whole truth. Whatever the Apostles received, that they were enjoined to teach [Mt 10:27; 28:20]. And that whole truth the Apostles taught, orally and in writing, committing it as the deposit to the Bishops whom they left in their place, and, under inspiration of God the Holy Ghost, embodying it in Holy Scripture. (p. 37)

Again, Scripture doesn’t teach “inscripturation”: the notion that all of the truth God wanted to preserve for posterity is in the Bible, and infallibly only there. John 20:30 informs us that “Jesus did many other signs . . . not written in this book.” John 21:25 refers to “many other things which Jesus did” that were so numerous that a written record would be such that “the world itself could not contain” all of it. Certainly this is hyperbole, but in any event, it’s referring to a lot of extrabiblical material that — it stands to reason — could have been largely or wholly contained in oral traditions passed down.

At least we know from the testimony of those who followed, that they taught it orally in all its great outlines; and St. Paul himself says, “I have not shunned to declare to you the whole counsel of God.” It does not indeed absolutely follow, that they so taught in detail all which is contained in Holy Scripture. (p. 37)

Nor does it absolutely follow that we must deny that there was a great deal of the apostolic deposit not contained in Scripture, and beyond it (though in harmony with it), or if contained at all, not explicitly spelled out.

How much, e. g., is taught in the Epistles incidentally, in answer to doubts which had arisen, whether this were so or no, even as to Apostolic teaching, or in correction of nascent heresies! But there is this difference between the teaching of the Apostles and that of the Church after them, that what the Apostles taught as the original and Fountain-head, that the Church only transmitted. (p. 37)

Again, we agree. But all doctrines develop as well, which is consistent with being present from the beginning. They were simply mostly primitive and basic at first.

According to the Council of Trent, then, as well as ourselves, the revelation was finished in and through the Apostles. (p. 38)

Exactly right; in terms of the apostolic deposit. He cited Session IV in this regard. It references unwritten tradition as well as the Holy Scripture:

The sacred and holy, ecumenical, and general Synod of Trent . . . keeping this always in view, that, errors being removed, the purity itself of the Gospel be preserved in the Church; which (Gospel), before promised through the prophets in the holy Scriptures, our Lord Jesus Christ, the Son of God, first promulgated with His own mouth, and then commanded to be preached by His Apostles to every creature, as the fountain of all, both saving truth, and moral discipline; and seeing clearly that this truth and discipline are contained in the written books, and the unwritten traditions which, received by the Apostles from the mouth of Christ himself, or from the Apostles themselves, the Holy Ghost dictating, have come down even unto us, transmitted as it were from hand to hand; (the Synod) following the examples of the orthodox Fathers, receives and venerates with an equal affection of piety, and reverence, all the books both of the Old and of the New Testament–seeing that one God is the author of both –as also the said traditions, as well those appertaining to faith as to morals, as having been dictated, either by Christ’s own word of mouth, or by the Holy Ghost, and preserved in the Catholic Church by a continuous succession. (Decree Concerning the Canonical Scriptures: beginning)

Photo credit: portrait of Pusey from For all the Saints (18 September 2014).

Summary: This is the first of two replies to E. B. Pusey’s Eirenicon (1866). Here I joyfully note many areas of agreement and discuss sola Scriptura and an infallible teaching Church.