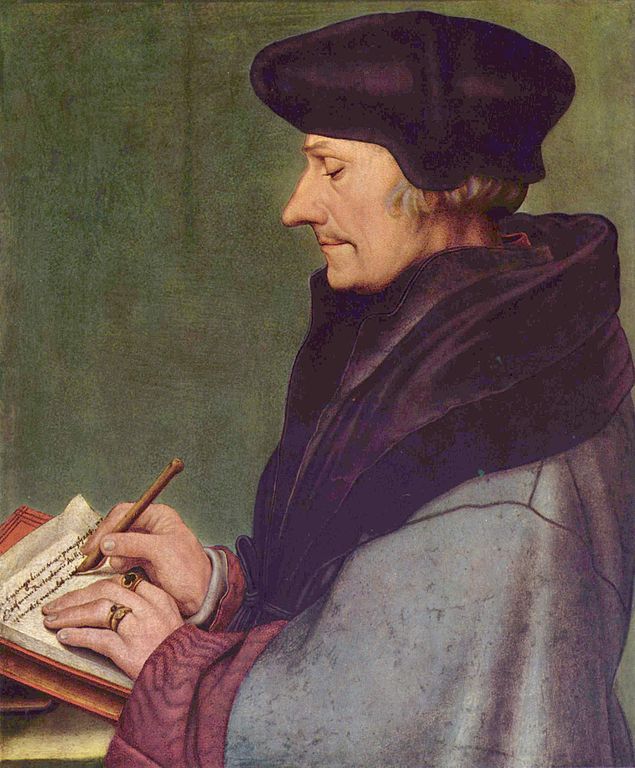

Desiderius Erasmus (1466/1469-1536); portrait (1523) by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/1498-1543) [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

From: Peter Macardle and Clarence H. Miller, translators, Charles Trinkhaus, editor, Collected Works of Erasmus, Vol. 76: Controversies: De Libero Arbitrio / Hyperaspistes I, Univ. of Toronto Press, 1999.

* * * * *

I have always hated factions. Up to now I wanted to stand alone, as long as I am not separated from the Catholic church. There was no reason for you to be afraid since you, together with your guard of sworn adherents, had to deal with a single person, and unarmed at that. But, you say, ‘you are armed with eloquence.’ If I have any, I certainly didn’t use it against you, and I dispensed not only with that weaponry, but also with the authority of the princes of the church, which by itself could be thought to be weapon enough for me. What was the point of absolving yourself of any fear of a single, unarmed person, since you have so courageously scorned both popes and emperors and battalions of theologians? But on these points you simply wanted to play the rhetorician. (p. 116)

There has to be some end to disputing. It is you who are forcing us to take up the matter all over again by calling into doubt, indeed by dislodging and demolishing, what has been fully approved, fixed, and immovable for so many centuries. (p. 121)

Which is more wicked: not to dispute about Christian dogmas beyond what is sufficient or to undermine them, throw them out, trample upon them, and decorate them with your kind of verbal decorations? (p. 126)

Is it right for just anyone to abrogate the judgments of the ancient Fathers which have been fully confirmed by the public decision of the church? Finally, why are you so outraged by the prophets who arise after you? (p. 129)

You can be sure of this, Luther, I do not entirely agree with any dogma of yours (I mean those that have been condemned) except that what you write about the corrupt morals of the church is truer than I would wish. (p. 139)

And then, what need is there for simple Christians to dispute about contingencies and the will as merely passive, since the magisterium of the church regards as settled that the will does do something but that what it does is ineffectual unless grace constantly lends its aid? Christian people have held this doctrine for fifteen hundred years, nor is it right to dispute about it, except in a restrained way and so as to better establish what the church has handed down. (p. 139)

It is not only excessively curious but also wicked to call into question, as you do, what the church has accepted with such an overwhelming consensus. (p. 140)

. . . if what the church has decided is true and indubitable, it is not safe for the ignorant multitude to hear the reasons, protestations, and oaths for the other side. But this is what I was urging, that simple people be content to accept the Catholic opinion, believing and holding what they have received, that is, the very thing you have undertaken to impugn. (p. 161)

I think that those who dispute about frivolous questions are more acceptable than those who by their disputations call back into debate matters about which the church has long since decreed that there should be no disagreement, having condemned what is false and approved what is true. (p. 163)

If I handle Holy Scripture with less learning, at least I do so cautiously and with reverence, following in the footsteps of the orthodox and fearing to depart from the decisions of the church. (p. 176)

If you are influenced by the judgment of the church, what you assert is human fabrication, what you fight against is the word of God. If you are not, even so you should deploy very clear arguments to prove what you assert before you command us to go over to your position, which is at odds with so many luminaries of the church and even with the public judgment of the church. (p. 181)

. . . arguments which would make us believe with certainty that you and your few adherents teach the truth, while so many Doctors of the church, so many universities, councils, and popes etc. were blind, even though both sides have Scripture in common. (p. 197)

. . . we should be shown some reason why we can safely believe in your teaching, rejecting the doctrine handed down by so many learned and famous men and accepted by the whole Christian world with such an overwhelming consensus. You try many ways to avoid this knot. (p. 200)

We are dealing with this: would a stable mind depart from the opinion handed down by so many famous men famous for holiness and miracles, depart from the decision of the church, and commit our souls to the faith of someone like you who has sprung up just now with a few followers, although the leading men of your flock do not agree either with you or among themselves — indeed though you do not even agree with yourself, since in this same Assertion you say one thing in the beginning and something else later on, recanting what you said before. (p. 203)

In A Discussion I do not employ the authority of either popes or councils or orthodox teachers to support free will, and even if I had done so, that would have been somewhat more tolerable than your citing of Melanchthon’s pamphlet as if it had the same authority as canonical Scripture. (p. 295)

In A Discussion I do not defend my own teaching but that of the church, but I do so without the assistance of the church, and I defend it from Holy Scripture, not as a fabrication of men but as the determination of Holy Scripture. (p. 205)

And here once more you have the impudence to scoff at orthodox Greek writers whom you deprive of all authority by a marvellous assumption, that the saints have sometimes erred because they are human . . . (p. 207)

Therefore do not insist that on the issue of free will you have the advantage of having Augustine so often on your side — as you boast, though I will soon show that this is quite false — lest we turn your comparison back against you. Or if you deprive them [the Church Fathers] of all authority, stop making use of their testimony. If they said many things devoutly, many things excellently, although they sometimes made mistakes, allow us to make use of what they said well, as you claim the right to do also. . . . It seems that up to now you have not ranted and raved enough against the most approved Doctors of the church unless you accuse St Jerome of impiety, sacrilege, and blasphemy because he wrote, ‘Virginity fills up heaven; marriage, the earth.’ (pp. 208-209)

You rant and rave thus against Jerome, but you do not allow anyone to disagree with you, however courteously. . . . I said it is not credible that God for so many centuries should have overlooked such a harmful error in his church without revealing to some of his saints the point which you contend is the keystone of the teachings in the gospel . . . (pp. 209-210)

But the whole drift of your reasoning is to make us understand that it is unknown who the saints are and what the church is . . . in such a way that the church of the saints seems to be where it is not, and, on the other hand, is where it does not seem to be . . . But when you declaim all this so copiously, you do nothing but confound and entirely subvert all heretical conventicles . . . How, then, are you sure that Wyclif was a holy man and the Arians were heretics? Is Wyclif holy precisely because he was condemned by the church which you call papistical? By the same token you will say that Arius was holy because he was condemned by the same church. At this point if you appeal to Scripture, did the Arians have any lack of Scripture? No, they did not, you will say, but they interpreted it wrongly. But how can we be sure of that except that the church rejected their interpretation and approved that of the other side? The same could be said of Pelagius . . . But let us grant it is possible that a general council is so corrupt that either there is no one moved by the Spirit of God, or if there is, he is not listened to, and that a conciliar decree is issued from the opinion of evil men, still it is more probable that the Spirit of God is there than in private conventicles, where the spirit of Satan is quite likely to be detected . . . I think it is safer to follow public authority rather than the opinion of someone or other who scorns everyone and boasts of his own conscience and spirit. If it is enough to say, ‘I have the Spirit,’ then we will have to believe many people urging various opinions upon us, and if the opinions disagree with one another they cannot be true . . . other things being equal, the greater probability lies on the side of what is approved by such men and confirmed by the public authority of the church rather than with what someone or other brought up on his own. (pp. 210-211)

As it is, since you confess that you are not certain where the saints are, where the true church is which does not err, either we will waver in uncertainty or we will follow what is nearer to the truth. (p. 211)

But if we posit an equal balance in the things by which you wish to be judged and the opinion of men is wavering in the balance, I ask you whether the authority of the ancient Fathers and the church should have any weight. . . . it should have enough weight, when the scale is evenly balanced, to incline us towards those who have been commended for so many centuries by the public favour of the whole world than towards those who are commended for no other reason than that they are baptized. And so if you insist that their authority has no value in confirming an opinion, then neither does yours or anyone else’s. (p. 213)

Why should it be so monstrous if, when some ambiguity or other arises in Scripture, we ignorant souls should prefer to consult the see of Rome rather than that of Wittenberg, which is full of disagreements at that? And who would believe the church of Rome if it should make pronouncements without Scripture? Nor does it interpret Scripture without the help of a council made up of learned men. You interpret at your own whim, with the help of your spirit, which is unknown to us . . . (p. 224)

. . . you demand that we reject their [the Church Fathers’] authority, that we hold to your teachings as if they were articles of the faith. At least grant us, for their teachings as well as yours, the same right to suspend judgment about either. (p. 225)

And I do not bring up how numerous and gifted they [the Church Fathers] were except to force you to bring forth a manifest argument by which we may know that we can safely believe in you and piously diverge from them. (p. 226)

The church has judged the Arians, and you approve of her judgment. But the same church condemned your teachings. (p. 232)

There [Luther’s Commentary on the Psalms] you call the ancient, orthodox writers consummately orthodox, holy, and learned; here you laugh at me for attributing holiness to them, while you charge them with blindness, ignorance, even blasphemy and sacrilege. And you can find no other excuse that would enable them to be saved except that they meant something different from what they wrote or repented of their error before they died. (p. 238)

. . . I called into question which interpretation we should follow, that of the ancient Fathers, which has been approved for so many centuries, or yours, which has sprung up so recently. (p. 244)

I do not require anyone to reject the opinion of all of them [the Church Fathers] on a matter of such great importance and to believe me alone — which is what you do, and not on this dogma alone, entreating and even demanding assent as rightfully due to you, threatening to trample in the mire of the streets whoever resists you as you preach the word of God. Therefore fairness requires that you give us firm arguments showing us why your judgment alone should carry more weight with us than that of so many great men . . . (p. 245)

What a convenient crack you have found here, one through which you can slip away whenever you are confronted with the authority of the ancient Fathers: they didn’t mean this, but rather they brought such things forth with a wandering pen and a meandering mind. And all the time you do not see that this device of yours can be turned back against you, not only by us but also by your followers . . . if it should happen that we seemed equal in testimonies out of Scripture and judgment hung in the balance, wavering in either direction, I asked whether it seemed right in this state of affairs that the authority of the ancients, together with the decision of the church, should certainly have a tiny bit of influence to make us more inclined towards their judgment rather than yours. . . . Place, then, free choice in the middle, held in good faith by the Catholic church for more than thirteen hundred years. Place yourself on one side assailing it with the assistance of Scripture and me on the other side defending it with the same assistance. Add spectators who, like me, think all our evidence is equal, although you demand to be at one and the same time both contestant and umpire and superintendent of the games. Who will award the prize either to you or to me, and by whose choice shall free choice be preserved or else destroyed? (pp. 249-250)

Now look at the laws which you prescribe, though you are not yet the victor: lay down whatever arms are supplied by the ancient orthodox teachers, the schools of the theologians, the authority of councils and popes, the consensus of the whole Christian people over so many centuries; we accept nothing but Scripture, but in such a way that we alone have authoritative certainty in interpreting it; our interpretation is what was meant by the Holy Spirit; that brought forward by others, however great, however many, arises from the spirit of Satan and from madness; what the orthodox taught, what the authority of the church handed down, what the people of Christ embraced, what the schools defend is the deadly venom of Satan; what I teach is the spirit of life; believe that in Scripture there is no obscurity at all, not even so much as to need a judge; or, though all are blind, I am not blind; for I am conscious that I have the Spirit of Christ, which enables me to judge everyone but no one to judge me; I refuse to be judged, I require compliance; let no one be the least bit moved by the multitude, the magnitude, the breadth and depth, the miracles, the holiness of the church’s saints; they all were lost if they meant what they wrote, unless perhaps they came to their senses before the last day of their lives; whoever does not believe my proofs either lacks common sense or commits blasphemy against the Holy Spirit and subverts Christianity. If we accept such laws as these, the victory is indeed yours. Then again, you demand that we not believe the ancient orthodox Fathers because they sometimes disagreed amongst themselves, whereas the few of you fight very much with each other about the prophets, images, church rules, baptism, the Eucharist; and you want us nevertheless to believe your teachings, especially because every day we expect new ones. And we are called blasphemous because we still cling to the old church and do not dare to join your camp . . . I am not making any of this up; I am saying what is certain and well known. (p. 261)

ADDENDUM

Erasmus’ Own Orthodoxy and Obedience to the Church

From the Catholic church I have never departed. I have never had the least inclination to enlist in your church — so little, in fact, that, though I have been very unlucky in many other ways, in one respect I consider myself lucky indeed, namely that I have steadfastly kept my distance from your league. I know that in the church which you call papistical there are many with whom I am not pleased, but I see such persons also in your church. But it is easier to put up with evils to which you are accustomed. Therefore I will put up with this church until I see a better one, and it will have to put up with me until I become better. And surely a person does not sail infelicitously if he holds to a middle course between two evils. (p. 117)

But let me show you how you have slandered me twice over: first I myself explicitly exclude from Scepticism whatever is set forth in Sacred Scripture or whatever has been handed down to us by the authority of the church. (p. 118)

I think it is sufficiently clear from my writings how much I attribute to Sacred Scripture and how unwaveringly I am in the articles of faith. On these points I am so far from desiring or having a Sceptical outlook that I would not hesitate to face death to uphold them. . . . now that the church has defined them [various “controverted teachings”] also, I have no use for human arguments but rather follow the decision of the church and cease to be a Sceptic. (pp. 118-119)

Whatever has been handed down as part of our faith is not to be sifted and searched so as to call it into question; rather it is to be professed. . . . Nor do I condemn in an unqualified way those who engage in moderate disputation, seeking to investigate some point which is not expressed in Sacred Scripture or defined by the church, but rather those who indulge in fierce and destructive strife about such matters. . . . I do not condemn moderate investigation but rather obstinate strife to the detriment of religion and harmony. (p. 120)

But I do not place more hope or find more consolation anywhere than in Holy Scripture, from which I believe I have derived so much light that I may hope for eternal salvation by the mercy of God without any of your contentious dogmas. And so I have no less reverence for Scripture than those who honour it most devoutly . . . the decrees of the Catholic church, especially those issued by general councils and fully approved by a consensus of Christian people, carry such weight with me that, even if my tiny intellect cannot fully understand the human reasons underlying what is prescribed, I will embrace it as if it were an oracle issued by God, nor will I violate any regulation of the church unless it is absolutely necessary to have a dispensation from the law. And I would be enormously displeased with myself and would suffer mental torment if the leaders of the church had directed at me the judgment they have pronounced against you . . . Follow your bent and make whatever interpretation you wish, call me a dyed-in-the-wool papist. You will not be able to impugn my attitude in any way, except that together with all good men I have desired the correction of the church, in so far as that can be done without serious and violent disturbances. (p. 127)

In Sacred Scripture, whenever the sense is quite clear, I want nothing to do with Scepticism, no more than I do concerning the decrees of the Catholic church. (p. 127)

For what does it mean to submit human understanding to the judgment of the church if not to believe what the church prescribes? I do not fully understand how the Father differs from the Son, how the Holy Spirit proceeds from both, though he is the son of neither one; and I am still more certain about this than about what I touch with my fingers. (p. 128)

I have always professed to be quite apart from your league; I am at peace with the Catholic church, to whose judgment I have submitted my writings, to detect any human error in them, for I know that they are very far from any malice or impiety. . . . It is not my place to wield the rod of judgment over the lives of popes and bishops. (p. 141)

Am I in danger of offending the Spirit of God if I am afraid to dissent from the church of Christ? Indeed the very reason I do not dare to entrust myself to you is that I am afraid to offend the Spirit of God. (p. 146)

I thought less badly of the man [Jan Hus] before I sampled the book he wrote against the Roman pontiff. What does such laborious abuse have in common with the Spirit of Christ? And in our discussion it does not matter what sort of pope condemned Hus; he is unknown to me, and popes have their own judge before whom they stand or fall. They are my judges; I am not theirs. (p. 230)

. . . in my Discussion I so distinctly and so clearly explain that there is no contradiction in saying that the sum and substance of a good deed should be attributed to God and asserting also that the human will does something, however tiny its share may be. (p. 154)

For why should anyone have faith in himself if he knows that he can neither begin nor complete anything without the help of God’s grace, to whom I profess that the sum and substance of all things rightly done ought to be attributed? Nor is there any difference between you and me except that I make our will cooperate with the grace of God and you make it completely passive. (p. 185)

How will a person rise up against God if he knows that he has in himself no hope of salvation without the singular grace of God, if he is persuaded that all human powers are of no avail for salvation without the aid of grace, especially since he is not unaware that everything he can do by his natural powers is the free gift of God? If a person wishes to cross the ocean, is he confident that he can achieve this without a ship and wind? And yet he is not idle while he is sailing. For professing free will does not tend to make a person attribute less to the mwercy of God but rather keeps him from not responding to operating grace and gives him reason to blame himself if he perishes. I exalt God’s mercy so much, I diminish human power so much, that in the matter of salvation no one can claim anything for himself, since the very fact of his existence and whatever he can do by his natural endowments is the gift of God. You exalt grace and demean mankind so much that you open another pit which we had closed over by attributing just a little bit to free will, namely that it accommodates itself to grace or turns away from grace. (p. 186)

When you say that a person taken captive by sin cannot by his own power turn his will to good unless he is blown upon by the breath of grace, we also profess this, especially if you mean turning effectively. (p. 188)

. . . you remove grace from free will, but when I say free will does something good, I join it with grace, and while it obeys grace it is acted upon and it acts felicitously. (p. 190)

Now see how you bear down upon me: it effects nothing without grace; therefore it does nothing at all with grace. Is this the trap you have set to catch me? (p. 190)