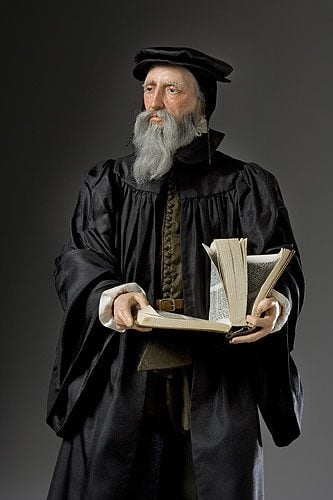

Historical mixed media figure of John Calvin produced by artist/historian George S. Stuart and photographed by Peter d’Aprix: from the George S. Stuart Gallery of Historical Figures archive [Wikimedia Commons / Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license]

***

This is an installment of a series of replies (see the Introduction and Master List) to much of Book IV (Of the Holy Catholic Church) of Institutes of the Christian Religion, by early Protestant leader John Calvin (1509-1564). I utilize the public domain translation of Henry Beveridge, dated 1845, from the 1559 edition in Latin; available online. Calvin’s words will be in blue. All biblical citations (in my portions) will be from RSV unless otherwise noted.

Related reading from yours truly:

Biblical Catholic Answers for John Calvin (2010 book: 388 pages)

A Biblical Critique of Calvinism (2012 book: 178 pages)

Biblical Catholic Salvation: “Faith Working Through Love” (2010 book: 187 pages; includes biblical critiques of all five points of “TULIP”)

*****

(4-29-09)

***

IV, 1:9-12

CHAPTER 1.

OF THE TRUE CHURCH. DUTY OF CULTIVATING UNITY WITH HER, AS THE MOTHER OF ALL THE GODLY.

9. These marks are the ministry of the word, and administration of the sacraments instituted by Christ. The same rule not to be followed in judging of individuals and of churches.

Hence the form of the Church appears and stands forth conspicuous to our view. Wherever we see the word of God sincerely preached and heard, wherever we see the sacraments administered according to the institution of Christ, there we cannot have any doubt that the Church of God has some existence, since his promise cannot fail, “Where two or three are gathered together in my name, there am I in the midst of them” (Mt. 18:20).

Sure, but Calvin presupposes what the entire “word of God” (i.e., correct doctrine) is in the first place. He neglects to see that this “word of God” must be in accord with what has been passed down and received (apostolic tradition and patristic consensus). His own theology, of course, fails this test (though elsewhere he will vigorously argue the contrary); therefore it is impossible for Calvin to successfully contend that his circles constitute the remnant and true Church while Catholicism (for the most part, in his jaded view of the Catholic Church) does not. His form of Christianity is only valid and true insofar as it conforms with received, traditional Christianity (i.e., Catholicism).

But that we may have a clear summary of this subject, we must proceed by the following steps:—The Church universal is the multitude collected out of all nations, who, though dispersed and far distant from each other, agree in one truth of divine doctrine, and are bound together by the tie of a common religion.

Protestantism certainly hasn’t agreed about “one truth of divine doctrine.” Even among Calvinists as a sub-group, there are constant in-fights and institutional splits (which is their only method — when all is said and done — of “resolving” disputes). I observe this all the time. What Calvin desires (doctrinal unity) can only be achieved in the Catholic Church.

[ . . . ]

10. We must on no account forsake the Church distinguished by such marks. Those who act otherwise are apostates, deserters of the truth and of the household of God, deniers of God and Christ, violators of the mystical marriage.

We have said that the symbols by which the Church is discerned are the preaching of the word and the observance of the sacraments, for these cannot anywhere exist without producing fruit and prospering by the blessing of God. I say not that wherever the word is preached fruit immediately appears; but that in every place where it is received, and has a fixed abode, it uniformly displays its efficacy. Be this as it may, when the preaching of the gospel is reverently heard, and the sacraments are not neglected, there for the time the face of the Church appears without deception or ambiguity and no man may with impunity spurn her authority, or reject her admonitions, or resist her counsels, or make sport of her censures, far less revolt from her, and violate her unity (see Chap. 2 sec. 1, 10, and Chap. 8 sec. 12). For such is the value which the Lord sets on the communion of his Church, that all who contumaciously alienate themselves from any Christian society, in which the true ministry of his word and sacraments is maintained, he regards as deserters of religion.

The unending irony of the revolutionary and schismatic (as Calvin was) commending the nobility and virtue of Christian unity . . . Again, he says the right thing, but does the wrong thing, in deciding to reject the Holy Catholic Church, headed in Rome by the pope, and with an unbroken history of orthodoxy all the way back to Christ.

So highly does he recommend her authority, that when it is violated he considers that his own authority is impaired. For there is no small weight in the designation given to her, “the house of God,” “the pillar and ground of the truth” (1 Tim. 3:15).

How often do we hear this passage cited by Protestants (or Calvinists)?! These days, it is mostly Catholics who bring attention to it.

By these words Paul intimates, that to prevent the truth from perishing in the world, the Church is its faithful guardian, because God has been pleased to preserve the pure preaching of his word by her instrumentality, and to exhibit himself to us as a parent while he feeds us with spiritual nourishment, and provides whatever is conducive to our salvation.

I’ve dealt with this aspect of Calvin’s reasoning in past entries. It sounds extraordinarily Catholic, but this consciousness is largely lost to Calvinists today, and Calvin cannot consistently apply this principle in his own domain because he has no authority and because his rule of faith (sola Scriptura and private judgment: exemplified by Luther’s intransigence and entirely subjective appeal at the Diet of Worms) undermines it

Moreover, no mean praise is conferred on the Church when she is said to have been chosen and set apart by Christ as his spouse, “not having spot or wrinkle, or any such thing” (Eph. 5:27), as “his body, the fulness of him that filleth all in all” (Eph. 1:23). Whence it follows, that revolt from the Church is denial of God and Christ.

Indeed. Obviously, the dispute between Protestants and Catholics at this point has to do with determining what the Church is and where to find it. Calvin’s rhetoric about the Church, as far as it goes, is not inconsistent at all with Catholic notions. It’s what he doesn’t say and what he falsely assumes, that are the problems.

[ . . . ]

11. These marks to be the more carefully observed, because Satan strives to efface them, or to make us revolt from the Church. The twofold error of despising the true, and submitting to a false Church.

Wherefore let these marks be carefully impressed upon our minds, and let us estimate them as in the sight of the Lord. There is nothing on which Satan is more intent than to destroy and efface one or both of them—at one time to delete and abolish these marks, and thereby destroy the true and genuine distinction of the Church; at another, to bring them into contempt, and so hurry us into open revolt from the Church.

Amen!

To his wiles it was owing that for several ages the pure preaching of the word disappeared,

This is, of course, a self-serving, undemonstrated opinion, that presupposes the familiar “The Catholic Church fell away in [take your pick] 100, as soon as the Bible was completed and the last apostle died / 313 [Constantine] / 900 / with the Inquisition / in the early 16th century / at Trent” mentality. All these arguments fail miserably and are easily shot down. Calvin assumes some form of this throughout the Institutes.

and now, with the same dishonest aim, he labours to overthrow the ministry, which, however, Christ has so ordered in his Church, that if it is removed the whole edifice must fall.

Yet Calvin wars against bishops, popes, priests, continuing ecumenical councils, and maintains only a minimalist clergy.

How perilous, then, nay, how fatal the temptation, when we even entertain a thought of separating ourselves from that assembly in which are beheld the signs and badges which the Lord has deemed sufficient to characterise his Church! We see how great caution should be employed in both respects. That we may not be imposed upon by the name of Church, every congregation which claims the name must be brought to that test as to a Lydian stone.

How profoundly true!

If it holds the order instituted by the Lord in word and sacraments there will be no deception; we may safely pay it the honour due to a church: on the other hand, if it exhibit itself without word and sacraments, we must in this case be no less careful to avoid the imposture than we were to shun pride and presumption in the other.

And if it teaches novel, ahistorical doctrines contrary to the ones that have always been believed in the Catholic Church from the beginning, and consistently developed through the centuries, according to the Mind of that same Church, all Christians must avoid it.

12. Though the common profession should contain some corruption, this is not a sufficient reason for forsaking the visible Church. Some of these corruptions specified. Caution necessary. The duty of the members.

When we say that the pure ministry of the word and pure celebration of the sacraments is a fit pledge and earnest, so that we may safely recognise a church in every society in which both exist, our meaning is, that we are never to discard it so long as these remain, though it may otherwise teem with numerous faults.

In other words, the essentials define it, not the faults and corruptions in practice. Very true.

Nay, even in the administration of word and sacraments defects may creep in which ought not to alienate us from its communion. For all the heads of true doctrine are not in the same position. Some are so necessary to be known, that all must hold them to be fixed and undoubted as the proper essentials of religion: for instance, that God is one, that Christ is God, and the Son of God, that our salvation depends on the mercy of God, and the like.

All things concerning which Catholics and Calvinists are in full agreement . . .

Others, again, which are the subject of controversy among the churches, do not destroy the unity of the faith; for why should it be regarded as a ground of dissension between churches, if one, without any spirit of contention or perverseness in dogmatising, hold that the soul on quitting the body flies to heaven, and another, without venturing to speak positively as to the abode, holds it for certain that it lives with the Lord?

Here Calvin starts to exhibit a fatal flaw in Protestant thinking that has perpetually plagued it from the beginning: this notion of “primary” vs. “secondary” doctrines, where the latter are regarded as “up for grabs”, so that Protestants may freely disagree with each other (and other Christians), thus adding a dangerous element of sanctioned doctrinal relativism. Catholics agree that some doctrines are far more important than others in the scheme of things, but they don’t take this additional step of throwing all less important doctrines up to individual subjectivism and philosophical relativism.

The general notion of “essential” or “central” and “secondary” doctrines is an unbiblical distinction. Nowhere in Scripture do we find any implication that some things pertaining to doctrine and theology were optional, while others had to be believed. Jesus urged us to “observe all that I have commanded you” (Matt. 28:19), without distinguishing between lesser and more central doctrines.

Likewise, St. Paul regards Christian Tradition as of one piece; not an amalgam of permissible competing theories: “the tradition that you received from us” (2 Thess. 3:6); “the truth which has been entrusted to you by the Holy Spirit” (2 Tim. 1:14); “the doctrine which you have been taught” (Rom. 16:17); “being in full accord and of one mind” (Phil. 2:2); “stand firm in one spirit, with one mind striving side by side for the faith of the gospel,” (Phil. 1:27). He, like Jesus, ties doctrinal unity together with the one God: “. . . maintain the unity of the Spirit in the bond of peace. There is one body and one Spirit, . . . one Lord, one faith, one baptism, . . .” (Eph. 4:3-5).

St. Peter also refers to one, unified “way of righteousness” and “the holy commandment delivered to them” (2 Pet. 2:21), while St. Jude urges us to “contend for the faith which was once for all delivered to the saints” (Jude 3). Luke 2:42 casually mentions “the apostles’ teaching” without any hint that there were competing interpretations of it, or variations of the teaching.

The words of the Apostle are, “Let us therefore, as many as be perfect, be thus minded: and if in anything ye be otherwise minded, God shall reveal even this unto you” (Phil. 3:15). Does he not sufficiently intimate that a difference of opinion as to these matters which are not absolutely necessary, ought not to be a ground of dissension among Christians?

But this passage has been yanked out of context and made to apply to supposed doctrinal latitude, when in fact, St. Paul, in this entire chapter of Philippians, is discussing striving towards a salvation not yet certainly obtained. When Paul says “be thus minded” he is referring to his statement immediately prior:

Philippians 3:12-14 Not that I have already obtained this or am already perfect; but I press on to make it my own, because Christ Jesus has made me his own. [13] Brethren, I do not consider that I have made it my own; but one thing I do, forgetting what lies behind and straining forward to what lies ahead, [14] I press on toward the goal for the prize of the upward call of God in Christ Jesus.

This has nothing to do with supposed doctrinal disputes, as Calvin oddly seems to think. Elsewhere in the same book (and many other times throughout his letters) Paul makes clear that there is one truth and unchanging set of doctrines that he has passed on, without any shade of variability:

Philippians 1:25,27 Convinced of this, I know that I shall remain and continue with you all, for your progress and joy in the faith, . . . Only let your manner of life be worthy of the gospel of Christ, so that whether I come and see you or am absent, I may hear of you that you stand firm in one spirit, with one mind striving side by side for the faith of the gospel,

Philippians 4:9 What you have learned and received and heard and seen in me, do; and the God of peace will be with you.

The best thing, indeed, is to be perfectly agreed, but seeing there is no man who is not involved in some mist of ignorance, we must either have no church at all, or pardon delusion in those things of which one may be ignorant, without violating the substance of religion and forfeiting salvation.

Protestants have too readily given in to human ignorance and mere subjectivism: that is a huge part of its problem. It lacks authority to maintain unity because its principles undermined Church authority from the beginning.

Here, however, I have no wish to patronise even the minutest errors, as if I thought it right to foster them by flattery or connivance; what I say is, that we are not on account of every minute difference to abandon a church, provided it retain sound and unimpaired that doctrine in which the safety of piety consists, and keep the use of the sacraments instituted by the Lord.

Again, the problem is that the original “minute” difference (even if we grant that it is, indeed, “minute” and inconsequential) quickly becomes a loophole, then a gaping hole, and finally, a broad highway of mutually contradictory opinions, leading to further dissent, sectarianism, acrimony, and doctrinal uncertainty. Nowhere does Holy Scripture ever envision such an uncontrolled state of affairs.

Meanwhile, if we strive to reform what is offensive, we act in the discharge of duty. To this effect are the words of Paul, “If anything be revealed to another that sitteth by, let the first hold his peace” (1 Cor. 14:30). From this it is evident that to each member of the Church, according to his measure of grace, the study of public edification has been assigned, provided it be done decently and in order. In other words, we must neither renounce the communion of the Church, nor, continuing in it, disturb peace and discipline when duly arranged.

This discipline has become practically impossible in Protestantism-at-large, because if discipline occurs, there is always the option of the person simply going to another denomination and starting afresh, or starting a new denomination altogether. There is no “Church” to speak of, given this absurd institutional division and multiplicity of competing sects.