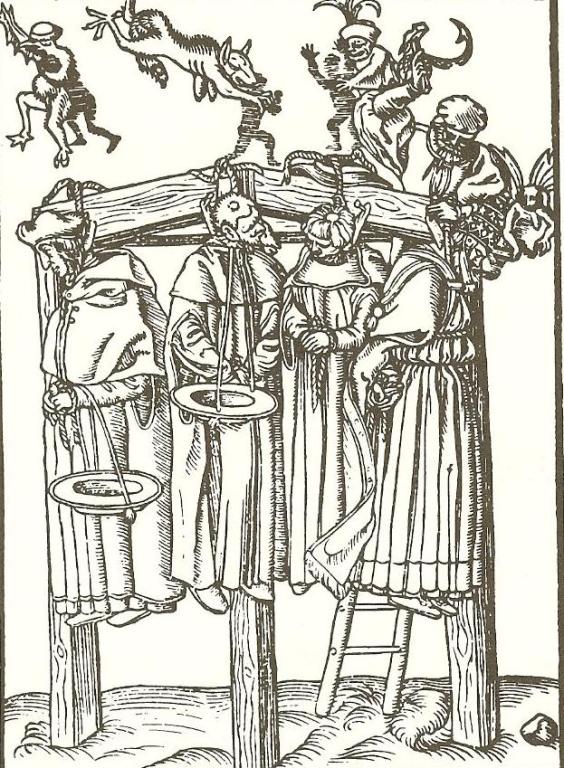

Just Reward for the Most Satanic Pope and His Cardinals: “hanging” woodcut by Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472-1553), commissioned by Martin Luther in 1545. Luther’s accompanying text reads: “If the pope and cardinals were to receive temporal punishment on earth, their blasphemous tongues would deserve what is rightly depicted here.”

* * * * *

Reformed Protestant apologist, polemicist and Luther defender James Swan was recently objecting to an Anabaptist polemicist who was raving against Martin Luther on the large CARM discussion board, saying that he was (among other things), “a demon possessed wicked butcher” and “responsible for the death of untold thousands.”

The Anabaptist highlighted a 1540 Luther utterance, recorded in Table-Talk (German versions only): “If I had all the Franciscan friars in one house, I would set fire to it.” Swan rightly observed that this was hyperbole, and was then mocked by the Anabaptist, who took it literally.

Swan (on the side of the angels for a change) then demonstrated at length that the citation was derived from Catholic Luther biographer, Hartmann Grisar, and he also noted what Grisar said about it (how he interpreted it):

But what of Luther’s vicious comments to burn the Franciscans alive? There’s an interesting aspect of Grisar’s context that Luther’s intolerant harsh words are found in. Immediately after the quote under scrutiny, Grisar says that it would be foolish to think Luther seriously wanted to kill Roman Catholic clergy. Grisar’s words stand as a sharp rebuke of the Anabaptist detractor who posted the quote taken from Grisar:

No one, in the least familiar with Luther s writings, will be so foolish as to believe that it was really his intention to kill the Catholic clergy and monks. His bloodthirsty demands were but the violent outbursts of his own deep inward intolerance. They were called forth occasionally by other alleged misdeeds of Popery, of its advocates and friends, for instance, by the burdensome taxes imposed by the Church, by her use of excommunication, and by the action taken against the Lutherans, particularly by the resolutions of the Diets for the suppression of Protestantism. Nor must we forget that the religious dissensions grew into a sort of permanent warfare and that war tends to produce effusions such as would be unthinkable in times of peace; nor was the warlike feeling a monopoly of the Lutheran side. (p. 247).

I’m glad to see that Swan discovered this citation. Part of it was used in my own paper, Luther’s Inflammatory Rhetoric & the Peasants’ Revolt (1524-1525), originally uploaded on 10-31-03. I cited Grisar’s words in general defense of Luther not personally advocating bloodshed and violence: “No one . . . will be so foolish to believe that it was really his intention to kill the Catholic clergy and monks. His bloodthirsty demands were but the violent outbursts of his own deep inward intolerance.”

Since Swan has been quite fond of citing previous versions of my papers after I revise them, I note that this one is documented from the date of 12-4-03 on Internet Archive. I also include many other opinions that Luther was not calling for actual violence, along these lines, from Christian historians (“P” = Protestant, “C” = Catholic):

Roland Bainton (P): “Luther had long since declared that he would never support the private citizen in arms, . . .”

Philip Schaff (P): “He deprecated, moreover, the resort to physical force in a spiritual warfare, . . . he was always opposed to the use of force, except by the civil magistrate, to whom the sword was given by God for the punishment of evil-doers. He thought that revolution was wrong in itself, and contrary to Divine order; that it was the worst enemy of reformation, and increased the evil complained of.”

Owen Chadwick (P): “Luther, not an extremist, often sounded like an extremist. He imagined a brave citizen meeting a ravening peasant with sword in hand, and had no idea that his language could encourage men to perpetuate outrages on defenceless peasants.”

Warren H. Carroll (C): “Luther had not intended these results of his preaching. As early as July 1524 he published a ‘Circular to the Princes of Saxony Concerning the Spirit of Revolt,’ in which he explicitly condemned the leading revolutionary, Thomas Munzer, for his incitement to armed rebellion, saying that he had never resorted to arms or favored doing so . . .”

Henry Daniel-Rops (C): “He roundly condemned the rebels’ claim to be fighting in the name of the Gospel, and their use of force to obtain justice.”

Philip Hughes (C): “[H]e lectured the peasants on the need to be patient and to remember that ‘he who takes up the sword will perish by the sword.’ “

At the same time, there are plenty of Protestant historians who agree with my contention that Luther was recklessly irresponsible in his “violent” rhetoric (and also art: see the top), that he intended hyperbolically and not literally. We see this motif in, for example, Owen Chadwick’s words above and in Bainton’s statement: “a complete dissociation of the reform from the Peasants’ War is not defensible.” And they are echoed by Catholic historian Joseph Lortz: often lauded and praised to the skies by James Swan as a “pro-Luther” Catholic historian (whereas he often classifies Grisar as “anti-Luther” or at least significantly biased against him):

Luther loosed a revolutionary storm against the special status of the clergy . . . Had he not injected this irresponsible tone into the atmosphere? . . . One cannot so defiantly and dauntlessly use provocative force to demolish the old church without having some of the socially oppressed drawing conclusions in the manner of the peasants. Such teachings were destined to become far more an impulse to insurrection in an atmosphere of total hatred, unbridled criticism and demagogic excitement. From destroying images it was not far to destroying monasteries . . .

In addition there is the matter of the frightful attacks against the princes Luther presumed to make in writings of 1523 and 1524. These adversaries were painted as raging, mad fools in that God’s wrath is being laid over them, in that the people would not have been a people were it not to have elevated its just complaints even to energetic and tumultuous resort to arms. Luther’s outburst of hatred — inescapable even in sermons — against one and every worldly authority not of his mind could only result in weakening authority in general. The new Gospel created a sort of mass consciousness among all the discontented . . . without that mass awareness the peasants scarcely would have evolved even the unity they did.

(“Reformation and Peasant Rebellion as Phenomena of Change,” in Kyle C. Sessions, editor, Reformation and Authority: The Meaning of the Peasant’s Revolt, Lexington, Massachusetts: D. C. Heath & Co., 1968, 9-16; from Die Reformation in Deutschland [Freiburg: Herder, 1962]; citation from 11-12, 14-15)

I’m glad to agree in a significant respect with the anti-Catholic James Swan, since the Bible says, “Behold, how good and pleasant it is when brothers dwell in unity!” (Ps 13:1, RSV). I wholeheartedly (and happily) agree that Luther was not “a demon possessed wicked butcher” or a “murderer” who was “responsible for the death of untold thousands.”

We appear to disagree, however, on the degree to which Luther’s “violent” metaphors and exaggerated rhetoric partially contributed (contrary to his will, and due to his extraordinary naivete) to the Peasants’ Revolt and other acts of violence. Many historians (Protestant, Catholic, and secular) thoroughly back me up on this, as presented in my lengthy two-part paper on that sad revolt (see their opinions near the end of Part II).

* * * * *