***

(1991)

***

Martin Luther

In 1522 Luther poured out his ire on the “asinine coarseness of the Thomists,” on “the Thomist hogs and donkeys,” on the “stupid audacity and thickheadedness of the Thomists.” (Grisar, I, 163; WA, X-2, 188-190, 206)

In my opinion dialectics can only be harmful to theologians . . . In theology . . . all syllogisms should be set aside. (Janssen, XIV, 123; LL, I, 127; letter to Spalatin, June 29, 1518)

St. Thomas Aquinas, according to Luther, was “a babbler and a chatterer.” (Janssen, XIV, 125) Aquinas and St. John Chrysostom were described as “idle prattlers” with the latter receiving additionally the appellation of “ambitious, haughty man” (Janssen, XIV, 190). One is reminded here of the pagan Greeks who, being unable to understand the intellectual, spiritual and theological brilliance of St. Paul, resort to derision: “What will this babbler say?” (Acts 17:18). It seems that Luther could only caricature men far more brilliant than himself. Here, as do often, he fought a”straw man” of his own invention, with mocking and slander (which is his technique against Catholicism in general). Examples of Luther’s opinion of other Church fathers:

St. Basil was utterly good for nothing . . . Origen he had already placed under the ban; and as for Gregory the Great, the devil had misled him with a childish heresy. St. Augustine also he would not trust, because he . . . had also often erred. St. Jerome: . . . of the faith, and of the true Church and way of life there was not a single word in his writings. (Janssen, XIV, 190)

Philip Melanchthon, in his letter to Johann Brenz (May 1531), illustrates how the Protestants had departed from patristic precedent:

Avert your eyes from such a regeneration of man and from the Law and look only to the promises and to Christ . . . Augustine is not in agreement with the doctrine of Paul, though he comes nearer to it than do the Schoolmen. I quote Augustine as in entire agreement, although he does not sufficiently explain the righteousness of faith; this I do because of public opinion concerning him. (Grisar, IV, 459-460)

Grisar, on p. 459, states that:

The letter was written by Melanchthon to Johann Brenz, but it had the entire approval of Luther, who even appended a few words to it. While clearly throwing overboard Augustine, it is nevertheless anxious to retain him.

[The documentation Grisar gives is “end of May, 1531”, Luthers Briefwechsel, 9, p. 18. This eleven-volume work was edited by L. Enders: Frankfurt & Stuttgart, 1884-1907; also 12 volumes, edited by G. Kawerau, Leipzig, 1910]

We find in Luther’s Table-Talk the following slams against St. Augustine and the Fathers:

Behold what great darkness is in the books of the Fathers concerning faith . . . Augustine wrote nothing to the purpose concerning faith. (DXXVI)

The more I read the books of the Fathers, the more I find myself offended. (DXXX)

Jerome should not be numbered among the teachers of the church, for he was a heretic. (DXXXV) (edition translated by William Hazlitt, Philadelphia: Lutheran Publication Society, n.d., 286-289)

For further reflections on this aspect of Protestantism’s frequent antipathy to the Church fathers, see the section, “Protestantism and the Fathers” on my Fathers of the Church web page.

The Decline of Education and Learning Within (and Because of) Protestantism

Early Protestantism caused:

. . . a decline in . . . learning. Complaints on this score begin to make themselves heard even in the first years after the introduction of the religious innovations; not only from Erasmus and other humanists, but also among the leaders of Protestantism itself, especially from Melanchthon, in whose letters and speeches, from 1522 till his death, laments on the decay of all the fine arts and all learning never cease. (Janssen, XIV, 235)

Numberless persons . . . speak in the bitterest language of the continuous decay of all high morals and fine culture . . . of the increasing depreciation of classical knowledge and of learning in general. (Janssen, XIII, 377)

In Germany, the period from about 1450 to the time of Luther, was:

. . . a time when culture penetrated to all classes of society . . . a time of extraordinary activity in art and learning . . . religious knowledge was zealously diffused, and the development of religious life abundantly fostered . . . The universities attained a height of excellence and distinction undreamt of . . . (Janssen, II, 287)

Protestantism would, unwittingly or not, undermine all this. Referring to Melanchthon, Janssen states:

His efforts for the revival of liberal culture in Wittenberg were completely shipwrecked. In his private letters he had no hesitation in attributing to the Wittenberg theologians the responsibility of the contempt of learning. (Janssen, III, 357; BR, I, 575, 604, 613, 679, 683, 695, 726, 894)

Melanchthon himself, according to a standard Protestant reference, “was far more humanistic than . . . most of the Reformers. He cared for learning as such . . .” (Cross, 898). This “moderate” testified mournfully:

The schools in Germany are deserted . . . among the people learning is universally hated, and even the princes . . . are filled with contempt and hatred for study. (Janssen, XIII, 328-329; BR, I, 756; letter to Arnold Burenius in 1542)

In Germany learning has become an object of contempt. (Janssen, XIII,328; letter to King Henry VIII in 1535)

The first widely-used philosophy text among Protestants was Metaphysics, by the Spanish Jesuit Suarez, published in 1605. (Janssen, XIV, 130)

The Melanchthonian Henry Moller, professor at Wittenberg, actually complained in 1569 of the:

. . . general decline of philosophical studies . . . How many ministers . . . are there at present in Germany who are not completely ignorant of these sciences? . . . The coarse, uneducated books scattered broadcast among the people in which philosophy is slandered and distorted, . . . can have no other result than the complete downfall of learning, the inroad of barbarism into the Church. (Janssen, XIV, 132-133; Dollinger, II, 496)

The Christian humanists of Germany and northern Europe, men of letters and advocates of reading, appreciation of past learning, and education, turned against the Protestants, by and large:

The intolerant dogmatism of the Reformers, their violence of speech, their sectarian fragmentation and animosities, their destruction of religious art, their predestinarian theology, their indifference to secular learning . . . all these shared in alienating the humanists from the Reformation. (Durant, 425)

Erasmus’ Critique of Protestant Anti-Intellectualism

Luther has covered us and good learning with hatred . . . The Church is overburdened with abuse of authority and . . . man-made decrees for the purpose of gain . . . but often an imprudent attempt at a cure makes things worse. What a mass of hatred Luther is bringing down on good learning and Christendom! (Phillips, 171; in 1521)

I greatly wonder . . . what god has stirred up the heart of Luther, in so far as he assails with such license of pen the Roman pontiff, all the universities, philosophy, and the mendicant orders. (Erasmus, 152; letter to Jodocus Jonas, May 10, 1521)

Wherever Lutheranism prevails, learning and liberal culture go to the ground. (Janssen, III, 355; letter to Pirkheimer)

The study of tongues and the love of fine literature is everywhere growing cold. Luther has heaped insufferable odium on it. (Grisar, VI, 32)

Regarding the downfall of the schools of Nuremberg, Erasmus wrote:

All this laziness came in with the new Evangel. (Grisar, VI, 32)

Luther responded in his own inimitable fashion:

I hate Erasmus! . . . I hate him from the bottom of my heart . . . I consider Erasmus to be the greatest enemy Christ has had these thousand years past. (Daniel-Rops, 77; Table-Talk)

Zwingli, who, like Luther, had once admired Erasmus, also split from him:

When I admonished Zwingli in a friendly way he wrote back disdainfully: “What you know is of no use to us; what we know is not for you.”

As if he had been caught up like Paul to the third heaven and learnt some mystery which was hidden to us earthly creatures! (Phillips, 195)

Sources

WA = Weimar Ausgabe edition of Luther’s Works (Werke) in German, 1883. “Br.” = correspondence.

BR = Bretschneider, editor, Corpus Reformation, Halle, 1846.

LL = Luther’s Letters (German), edited by M. De Wette, Berlin: 1828

F. L. Cross and E. A. Livingstone, editors, The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 2nd ed., 1983.

Henri Daniel-Rops, The Protestant Reformation, vol. 2, translated by Audrey Butler, Garden City, New York: Doubleday Image, 1961.

Johann Dollinger, The Reformation, Regensburg, 1848.

Will Durant The Reformation, (volume 6 of 10-volume The Story of Civilization, 1967), New York: Simon & Schuster, 1957.

Desiderius Erasmus, Christian Humanism and the Reformation, (selections from Erasmus), edited and translated by John C. Olin, New York: Harper & Row, 1965 (orig. 1515-34).

Hartmann Grisar, Luther, translated by E. M. Lamond, edited by Luigi Cappadelta, six volumes, London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., 1917.

Johannes Janssen, History of the German People From the Close of the Middle Ages, 16 volumes, translated by A. M. Christie, St. Louis: B. Herder, 1910 (orig. 1891).

Margaret Phillips, Erasmus and the Northern Renaissance, New York: Collier Books, 1965.

***

Related reading:

Early Protestant Antipathy Towards Art (+ Iconoclasm)

Early Protestant Hostility Towards (and Ignorance of) Science

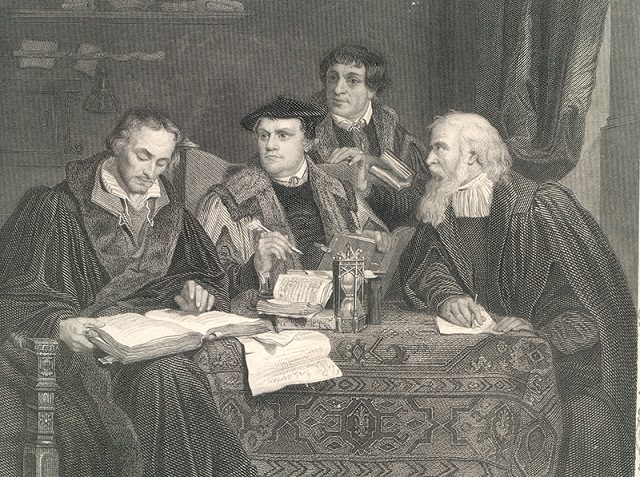

Photo credit: Philip Melanchthon (left) and Martin Luther. Image courtesy of Concordia Historical Institute. [“Gallery”]

***