The Judaizers were Christians who took a different approach to law and grace than the Church at length decided to take.

***

The New International Dictionary of the Christian Church (edited by J. D. Douglas, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zodervan, 1978, “Judaizers”, p. 554), states about the Judaizers:

A party of Christians in the early church who thought it was necessary that Gentile converts to Christianity should be circumcised and observe the Jewish law — in fact that they should become Jews in order to become Christians.

There are Protestant commentators (some, e.g., from the school of “the New Perspective on Paul”) who think they (i.e., the parties doing the “influencing”) were Jews or followers of sectarian offshoots of Judaism, but opinions differ, so that, in any event, this is not a Protestant-Catholic divide, but a scholarly one of differing opinions in good faith.

Here is a great deal more evidence for my assertions, from non-Catholic scholarly sources:

In the early Church a section of Jewish Christians who regarded the OT Levitical laws as still binding on Christians. They tried to enforce on the faithful such practices as circumcision and the distinction between clean and unclean meats. Their initial success brought upon them the strong opposition of St. Paul, much of whose writing was concerned with refuting their errors. (The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, second edition, edited by F. L. Cross and E. A. Livingstone, Oxford University Press, 1983, “Judaizers” [complete], p. 763)

Some Jewish Christians were so conservative that they demanded, in effect, that Gentiles had to become Jews in order to be true Christians. They insisted on circumcision and other Jewish legal requirements, and frowned on social contact with ‘unclean’ Gentiles. These ‘Judaizers’ appealed to the Jerusalem church . . . But Paul refused to tolerate any demands imposed on Gentile converts . . . (Eerdmans Handbook to The History of Christianity, editor: Tim Dowley, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans, 1977, “What the First Christians Believed,” by consulting editor David F. Wright, 97)

The great biblical scholar F. F. Bruce refused to take a stand one way or another, and remains “agnostic” on the question, stating (in a section on St. Paul’s letter to the Galatians):

It was evidently written by Paul to warn his Galatian converts against certain “trouble-makers” [footnote: Galatians 1:7; 5:12] who were urging upon them a line of teaching and course of action which, as he saw the situation, threatened to undermine the gospel which he had brought to them and which they had accepted. But even on the character and policy of these “trouble-makers” there is disagreement.

The view adopted here — provisionally, not dogmatically — . . . it is a natural conclusion, then, that the “trouble-makers” were judaizers . . . (Paul: Apostle of the Heart Set Free, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans, 1977, 179)

Yet Dr. Bruce does not specifically claim that they were Jews (or Christians). That such a thorough and respected New Testament scholar has such uncertainty on the matter, proves my point and disproves the claims that the Judaizers were obviously Jews and non-Christians.

Some scholars are of the opinion that these were Jews and precursors of what later became the Ebionite heresy, or even worse, a strain of Gnosticism (Bruce mentions the latter possibility). Philip Schaff (one of the “patron saints” of the general Protestant view of Church history) holds to the “primitive Ebionite Jews” explanation (History of the Christian Church, Volume I: 565-567). Some scholars (e.g., Harnack and Hort) have equated the Ebionites with the Nazarenes (i.e., 4th-century patristic usage rather than biblical).

Renowned Pauline scholar Sir William M. Ramsay held that the Judaizers were a “party” within the Christian Church, in his famous work, St. Paul: the Traveller and the Roman Citizen (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1897; reprinted: Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Book House, 1962).

In recounting what he feels to be Paul’s thought processes in his letter to the Galatians, he refers to “Judaistic Christians” twice (p. 188) and “the superiority of the free to the Jdaistic Christians is illustrated . . .” (p. 189). Other phrases he uses are: “Judaising party in the Church” (p. 160), “Judaising party” (p. 170; and twice on p. 172), “Judaistic party” (p. 184), “extreme Judaistic party in the Church” (p. 375; implying that there was even a lesser such “Judaizing party” as well; otherwise, why the descriptor “extreme”?).

More modern biblical scholars and historians are even more interesting. James D. G. Dunn is always informative and fascinating, even when one disagrees with him (as I do, not infrequently):

In Galatians Paul speaks of no less than three gospels. First, his own . . . (Gal. 2.7) . . . Second is the gospel for the Jews, ‘for the circumcision’ (2.7), represented by the ‘pillar apostles’, Peter in particular, centred on Jerusalem. Paul recognizes this Jewish version of the gospel as a legitimate form of Christian kerygma, appropriate to the Jews . . . in his view it involved a greater subjection to the law than he himself thought right (2.11-21). However, so long as the proponents of each of these two gospels recognized the validity of the other and did not seek to impose their own gospel on those who held to the other, Paul was content. But evidently the churches in Palestine had a legalistic right wing which opposed the law-free Gentile mission. Theirs is the ‘other gospel’ which Paul attacks in fierce language in 1.6-9. It is not finally clear whether Paul denied Christian status to this third gospel (1.7 probably means: it is not another gospel but a perversion of the gospel of Christ). But he leaves no doubt as to what he thought of the so-called ‘Judaizers” attempts to force their understanding of the gospel on others: it is no good news, the way of bondage; those who preach it are ‘sham Christians’, they have missed the full truth and ought to castrate themselves (2.4f; 5.12)! (Unity and Diversity in the New Testament, London: SCM Press, 2nd edition, 1990, 23-24)

We know from Gal. 2.4, not to mention Acts 15.1 and Phil. 3.2ff, that there was a strong party in the Palestinian churches, a powerful force in the Christianity of Jerusalem and Palestine, which insisted on circumcision for all converts. Paul calls them some very rude names — ‘false brethren’ (RSV), ‘sham Christians, interlopers’ (NEB — Gal 2.4), ‘dogs’ (Phil. 3.2) . . . But it is quite clear, from Gal. 2 and Acts 15 at least, that they were Jewish Christians — that is to say, a force within the Jerusalem community who could with justice claim to speak for Jewish believers in Judea . . . Here at once we recognize a form of Jewish Christianity which stands within the Christian spectrum at the time of Paul’s missionary work . . . (Ibid., 252-253)

Noted historian Donald Harman Akenson argues similarly in his recent book about the Apostle Paul. He states in a footnote near the end of the book that he refused to use the term “Judaizers” in his book because the relevant scholarly literature has not produced “sufficient agreement” on its meaning, and that it, therefore, could be a misleading term. That said, he proceeds with his own analysis:

[I]t is an unfortunate word . . . a useless word, for it makes us think we know more than we do. Saul uses the Greek verb “to Judaize” only once, and that is in Galatians 2:14 . . . Significantly, in the epistles wherein Saul denounces people whom later historians call “Judaizers,” Saul does not use the term “Judaizer.” It is an invention of the later church. Despite the absence of reliable evidence, most commentators and most present-day biblical scholars identify these “Judaizers” as being Gentiles who were followers of Yeshua but who also were deeply into one or more of the traditions of praxis that revolved through late Second Temple Judaism . . .

When Saul denounces unnamed persons for pushing Judahist praxis too strongly upon Gentiles, we should not assume that we know immediately who it was: it could have been lifelong Judahists who were allied to the Yeshua-faith; it could have been Gentiles who had become full proselytes to Judahism as well as followers of Yeshua; and it could even have been Judahists who themselves had no allegiance to Yeshua, but who recognized the Yeshua-faith as a branch of Judahism and therefore urged all of its members to carry out the full 613 commandments. Manifestly a term that is based on contradictory empirical foundations, it is neither descriptively nor analytically viable. It has to be abandoned and with it the overtones of the slur based on nearly two millennia of misreading of Saul: namely that anything smacking of “Jewish” practice was wrong and so said the first missionary of the faith. He didn’t. (Saint Saul: A Skeleton Key to the Historical Jesus, Oxford University Press, 2000, 289-290; footnote 9 for chapter seven)

***

(originally 6-7-07)

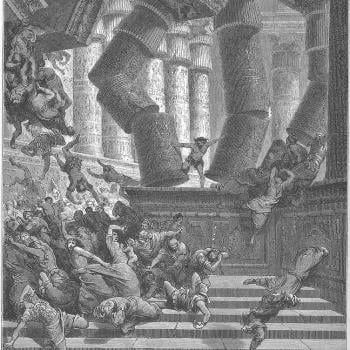

Photo credit: Portion of Herod’s wall for his temple, in Jerusalem, with the remnant of “Robinson’s Arch”. Taken by my wife Judy Armstrong during our trip to Israel in October 2014.

***