This is an installment of a series of replies (see the Introduction and Master List) to much of Book IV (Of the Holy Catholic Church) of Institutes of the Christian Religion, by early Protestant leader John Calvin (1509-1564). I utilize the public domain translation of Henry Beveridge, dated 1845, from the 1559 edition in Latin; available online. Calvin’s words will be in blue. All biblical citations (in my portions) will be from RSV unless otherwise noted.

Related reading from yours truly:

Biblical Catholic Answers for John Calvin (2010 book: 388 pages)

A Biblical Critique of Calvinism (2012 book: 178 pages)

Biblical Catholic Salvation: “Faith Working Through Love” (2010 book: 187 pages; includes biblical critiques of all five points of “TULIP”)

*****

IV, 1:20-23

***

CHAPTER 1.

20. Fifth objection. Answer to the ancient and modern Cathari, and to the Novatians, concerning the forgiveness of sins

Their moroseness and pride proceed even to greater lengths. Refusing to acknowledge any church that is not pure from the minutest blemish, they take offence at sound teachers for exhorting believers to make progress, and so teaching them to groan during their whole lives under the burden of sin, and flee for pardon. For they pretend that in this way believers are led away from perfection. I admit that we are not to labour feebly or coldly in urging perfection, far less to desist from urging it; but I hold that it is a device of the devil to fill our minds with a confident belief of it while we are still in our course.

This is highly important. Note that Calvin is discussing and urging the necessity of progressive sanctification. He is not resting on an abstract assurance, as if the believer needs no further vigilance and has no sense of process. This is quite different from the mindset of many of his followers today and various offshoots of his thought (the “instant salvation” / “absolute assurance” / “eternal security mindsets).

Accordingly, in the Creed forgiveness of sins is appropriately subjoined to belief as to the Church, because none obtain forgiveness but those who are citizens, and of the household of the Church, as we read in the Prophet (Is. 33:24).

How rare would such a thought be in many Protestant circles today! Calvin retains the corporate sense of even forgiveness of sins.

The first place, therefore, should be given to the building of the heavenly Jerusalem, in which God afterwards is pleased to wipe away the iniquity of all who betake themselves to it. I say, however, that the Church must first be built; not that there can be any church without forgiveness of sins, but because the Lord has not promised his mercy save in the communion of saints.

Another extremely important point . . . This is as far as it can be from the prevalent “me, my Bible, and the Holy Spirit” individualistic mentality we often observe today. That’s far more “American” than it is Catholic or even Calvinist, let alone biblical.

Therefore, our first entrance into the Church and the kingdom of God is by forgiveness of sins, without which we have no covenant nor union with God.

The Catholic applies this to baptismal regeneration, but alas, Calvin rejected that (though I believe some Calvinists argue that he did not reject it).

For thus he speaks by the Prophet, “In that day will I make a covenant for them with the beasts of the field, and with the fowls of heaven, and with the creeping things of the ground: and I will break the bow, and the sword, and the battle, out of the earth, and will make them to lie down safely. And I will betroth thee unto me for ever; yea, I will betroth thee unto me in righteousness, and in judgment, and in loving-kindness, and in mercies” (Hos. 2:18, 19). We see in what way the Lord reconciles us to himself by his mercy. So in another passage, where he foretells that the people whom he had scattered in anger will again be gathered together, “I will cleanse them from all their iniquity, whereby they have sinned against me” (Jer. 33:8). Wherefore, our initiation into the fellowship of the Church is, by the symbol of ablution, to teach us that we have no admission into the family of God, unless by his goodness our impurities are previously washed away.

Again, I would challenge the Calvinist as to what this means in concrete terms. If it is not in baptism, then from whence does it come? He is probably (I would guess) referring to sanctification, not imputed justification, because “cleanse them from all their iniquity” and “our impurities are previously washed away” are literally analogous to a real, in-this-life cleansing of sin, not a merely declared, forensic, abstract, extrinsic “cleansing.” It’s not totally clear what he means, so I am speculating a bit here.

21. Answer to the fifth objection continued. By the forgiveness of sins believers are enabled to remain perpetually in the Church.

Nor by remission of sins does the Lord only once for all elect and admit us into the Church, but by the same means he preserves and defends us in it. For what would it avail us to receive a pardon of which we were afterwards to have no use? That the mercy of the Lord would be vain and delusive if only granted once, all the godly can bear witness; for there is none who is not conscious, during his whole life, of many infirmities which stand in need of divine mercy.

This goes against the “eternal security” notion: i.e., when it is corrupted and used as a pretext for antinomian freedom from concerns of ongoing holiness. It seems to be a notion of ongoing forgiveness of sins, somewhat akin to the Catholic sacramental absolution, at least insofar as it is ongoing. But I doubt that Calvin would apply it in its entirety to that mechanism of forgiveness, so I will have to read on to see exactly what he means (particularly by the term “remission of sins”).

And truly it is not without cause that the Lord promises this gift specially to his own household, nor in vain that he orders the same message of reconciliation to be daily delivered to them.

This seems to imply a preaching function only; not a sacramental remission of sins and absolution.

Wherefore, as during our whole lives we carry about with us the remains of sin, we could not continue in the Church one single moment were we not sustained by the uninterrupted grace of God in forgiving our sins.

Now it is starting to sound more typically “Protestant” . . . the process is more subjective, internal, and abstract, rather than concrete and sacramental, and involving another human being (i.e., a priest).

On the other hand, the Lord has called his people to eternal salvation, and therefore they ought to consider that pardon for their sins is always ready. Hence let us surely hold that if we are admitted and ingrafted into the body of the Church, the forgiveness of sins has been bestowed, and is daily bestowed on us, in divine liberality, through the intervention of Christ’s merits, and the sanctification of the Spirit.

Calvin’s categorization of this process under “sanctification” shows that, for him, it has nothing directly to do with salvation. Indirectly it does, though, even for Calvin, since he holds that works are an essential manifestation of an authentic saving faith.

22. The keys of the Church given for the express purpose of securing this benefit. A summary of the answer to the fifth objection.

To impart this blessing to us, the keys have been given to the Church (Mt. 16:19; 18:18).

But also to St. Peter, preeminently and individually, which fact Calvin deliberately passes over.

For when Christ gave the command to the apostles, and conferred the power of forgiving sins, he not merely intended that they should loose the sins of those who should be converted from impiety to the faith of Christ; but, moreover, that they should perpetually perform this office among believers.

That sounds sacramental and very Catholic again . . . let’s see where Calvin goes form here.

This Paul teaches, when he says that the embassy of reconciliation has been committed to the ministers of the Church, that they may ever and anon in the name of Christ exhort the people to be reconciled to God (2 Cor. 5:20).

But how to be reconciled, is the question . . . Catholics agree that one can become right with God again, without the need of priestly absolution, in the matter of venial sin (it can aid in that but is not required), but not when mortal sin has occurred.

Therefore, in the communion of saints our sins are constantly forgiven by the ministry of the Church, when presbyters or bishops, to whom the office has been committed,

Calvinist bishops? What has happened to them, pray tell?

confirm pious consciences, in the hope of pardon and forgiveness by the promises of the gospel, and that as well in public as in private, as the case requires. For there are many who, from their infirmity, stand in need of special pacification, and Paul declares that he testified of the grace of Christ not only in the public assembly, but from house to house, reminding each individually of the doctrine of salvation (Acts 20:20, 21).

Calvin is now being more clear that he intends more or less a preaching function (which is classic “low church” Protestantism): tell people the message of reconciliation and they (by God’s grace and His will) will receive it of their own accord without need of sacramental absolution or even baptismal regeneration. I’ve dealt with this at length.

Calvin neglects to also include the transactional element of forgiveness of sins. The priest does not only, merely declare (by preaching or evangelizing) the availability of forgiveness and reconciliation through God’s grace, to be subjectively appropriated by the individual; he also brings it about as a sacramental agent. Calvin apparently rejects this latter element. But it is entirely biblical:

Matthew 16:19 I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven, and whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven.

Matthew 18:18 Truly, I say to you, whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven.

John 20:21-23 Jesus said to them again, “Peace be with you. As the Father has sent me, even so I send you.” And when he had said this, he breathed on them, and said to them, “Receive the Holy Spirit. If you forgive the sins of any, they are forgiven; if you retain the sins of any, they are retained.”

“Binding” and “loosing” were rabbinical terms that had to do with authority to punish or pardon. We see the Apostle Paul literally exercising these prerogatives with the Corinthians. He “binds” in 1 Corinthians 5:1-5 (what Catholics would call “imposing a penance”) and “looses” in 2 Corinthians 2:6-11. Paul forgives another man for a transgression that wasn’t personally committed against him, and instructs the Corinthians to do the same (the sin wasn’t committed against all of them, either). So both he and the Corinthians as a whole were acting as “God’s representatives” in the matter of forgiving sins (emphases added):

1 Corinthians 5:1-5 It is actually reported that there is immorality among you, and of a kind that is not found even among pagans; for a man is living with his father’s wife. And you are arrogant! Ought you not rather to mourn? Let him who has done this be removed from among you. For though absent in body I am present in spirit, and as if present, I have already pronounced judgment in the name of the Lord Jesus on the man who has done such a thing. When you are assembled, and my spirit is present, with the power of our Lord Jesus, you are to deliver this man to Satan for the destruction of the flesh, that his spirit may be saved in the day of the Lord Jesus.

2 Corinthians 2:6-11 For such a one this punishment by the majority is enough; so you should rather turn to forgive and comfort him, or he may be overwhelmed by excessive sorrow. So I beg you to reaffirm your love for him. For this is why I wrote, that I might test you and know whether you are obedient in everything. Any one whom you forgive, I also forgive. What I have forgiven, if I have forgiven anything, has been for your sake in the presence of Christ, to keep Satan from gaining the advantage over us; for we are not ignorant of his designs.

Three things are here to be observed. First, Whatever be the holiness which the children of God possess, it is always under the condition, that so long as they dwell in a mortal body, they cannot stand before God without forgiveness of sins.

Very true. And in the end these will have to literally be removed or cleansed, which is precisely why we believe in purgatory.

Secondly, This benefit is so peculiar to the Church, that we cannot enjoy it unless we continue in the communion of the Church.

Yes, but again, how is it appropriated by the individual in the Church, and from whom does it come on a human level, as a representative of God? That is our difference.

Thirdly, It is dispensed to us by the ministers and pastors of the Church, either in the preaching of the Gospel or the administration of the Sacraments, and herein is especially manifested the power of the keys, which the Lord has bestowed on the company of the faithful. Accordingly, let each of us consider it to be his duty to seek forgiveness of sins only where the Lord has placed it. Of the public reconciliation which relates to discipline, we shall speak at the proper place.

As far as I know, Calvin only allowed for the sacraments of baptism and the Eucharist, and neither in the traditional sense of a real regenerational change and the Real Presence of Christ on the altar after the consecration. I’m unaware that he retained the sacrament of absolution / reconciliation / confession. Perhaps I’ll learn differently, as I proceed.

23. Sixth objection, formerly advanced by the Novatians, and renewed by the Anabaptists. This error confuted by the Lord’s Prayer.

But since those frantic spirits of whom I have spoken attempt to rob the Church of this the only anchor of salvation, consciences must be more firmly strengthened against this pestilential opinion.

Calvin, like Luther, was already dealing with Protestant fanatics and sectarians to the “left” of him: the so-called “radical reformers.” This was of great concern to both of them, and they made no bones about being troubled by it. They don’t seem to figure out, however, that these sectarians were acting consistently upon Luther and Calvin’s new principles of authority: private judgment, absolute supremacy of the individual conscience, sola Scriptura in some form, etc.

In other words, where Luther and Calvin saw a qualitative, essential difference between themselves and these sectarians, Catholics see only a matter of degree, and a different place on the same essential spectrum, and see both parties using the same rule of faith, but applied in real life to a greater or lesser extreme. Calvin was certainly closer to the received Catholic tradition than these more radical factions, but not (from our Catholic perspective) as much closer as he himself assumed.

The Novatians, in ancient times, agitated the Churches with this dogma, but in our day, not unlike the Novatians are some of the Anabaptists, who have fallen into the same delirious dreams.

Just as I mentioned in my last comment (I’m replying as I read) . . .

For they pretend that in baptism, the people of God are regenerated to a pure and angelical life, which is not polluted by any carnal defilements.

It’s interesting that they have some notion of regeneration (which is correct and orthodox) but take it too far and act as if this wipes out any future sin.

But if a man sin after baptism, they leave him nothing except the inexorable judgment of God. In short, to the sinner who has lapsed after receiving grace they give no hope of pardon, because they admit no other forgiveness of sins save that by which we are first regenerated.

Which is far too rigorous and unscriptural (as well as remarkably unrealistic and untrue to human reality), as Calvin rightly observes . . .

But although no falsehood is more clearly refuted by Scripture, yet as these men find means of imposition (as Novatus also of old had very many followers), let us briefly show how much they rave, to the destruction both of themselves and others. In the first place, since by the command of our Lord the saints daily repeat this prayer, “Forgive us our debts” (Mt. 6:12), they confess that they are debtors.

Great point!

Nor do they ask in vain; for the Lord has only enjoined them to ask what he will give. Nay, while he has declared that the whole prayer will be heard by his Father, he has sealed this absolution with a peculiar promise. What more do we wish? The Lord requires of his saints confession of sins during their whole lives, and that without ceasing, and promises pardon.

Good as far as it goes . . . Calvin needs, however, to add the priestly, absolution element to have the entire biblical doctrine of confession.

How presumptuous, then, to exempt them from sin, or when they have stumbled, to exclude them altogether from grace? Then whom does he enjoin us to pardon seventy and seven times? Is it not our brethren? (Mt. 18:22)

Another wonderfully relevant and apt rejoinder . . .

And why has he so enjoined but that we may imitate his clemency? He therefore pardons not once or twice only, but as often as, under a sense of our faults, we feel alarmed, and sighing call upon him.

Exactly right (not forgetting the inherent limitations of his entire doctrine of forgiveness of sins).

***

(originally 5-15-09; rev. 12-19-18)

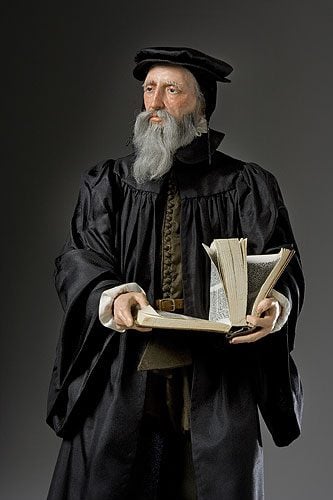

Photo credit: Historical mixed media figure of John Calvin produced by artist/historian George S. Stuart and photographed by Peter d’Aprix: from the George S. Stuart Gallery of Historical Figures archive [Wikimedia Commons / Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license]

***