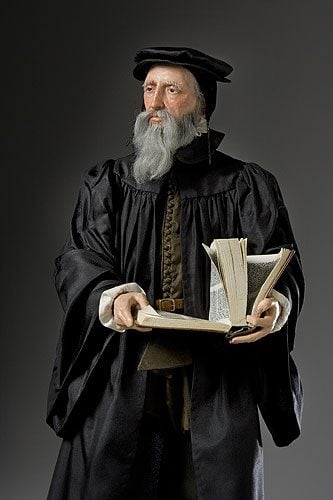

This is an installment of a series of replies (see the Introduction and Master List) to much of Book IV (Of the Holy Catholic Church) of Institutes of the Christian Religion, by early Protestant leader John Calvin (1509-1564). I utilize the public domain translation of Henry Beveridge, dated 1845, from the 1559 edition in Latin; available online. Calvin’s words will be in blue. All biblical citations (in my portions) will be from RSV unless otherwise noted.

Related reading from yours truly:

Biblical Catholic Answers for John Calvin (2010 book: 388 pages)

A Biblical Critique of Calvinism (2012 book: 178 pages)

Biblical Catholic Salvation: “Faith Working Through Love” (2010 book: 187 pages; includes biblical critiques of all five points of “TULIP”)

*****

IV, 3:8, 13

***

CHAPTER 3

In giving the name of bishops, presbyters, and pastors, indiscriminately to those who govern churches, I have done it on the authority of Scripture, which uses the words as synonymous.

Herein lies the error. Although there is indeed some overlap of terms and a less-than-rigid classification system in Scripture, still, bishops are said to have certain tasks that go beyond those of priests / pastors. Bishops (episkopos) possess all the powers, duties, and jurisdiction of priests, with the following important additional responsibilities:

1) Jurisdiction over Priests and Local Churches, and the Power to Ordain Priests: Acts 14:22; 1 Timothy 5:22; 2 Timothy 1:6; Titus 1:5.

2) Special Responsibility to Defend the Faith: Acts 20:28-31; 2 Timothy 4:1-5; Titus 1:9-10; 2 Peter 3:15-16.

3) Power to Rebuke False Doctrine and Excommunicate: Acts 8:14-24; 1 Corinthians 16:22; 1 Timothy 5:20; 2 Timothy 4:2; Titus 1:10-11.

4) Power to Bestow Confirmation (the Receiving of the Indwelling Holy Spirit): Acts 8:14-17; 19:5-6.

5) Management of Church Finances: 1 Timothy 3:3-4; 1 Peter 5:2.

In the Septuagint (the Greek translation of the Old Testament), episkopos is used for overseer in various senses, for example: officers (Judges 9:28; Isaiah 60:17), supervisors of funds (2 Chronicles 34:12, 17), overseers of priests and Levites (Nehemiah 11:9; 2 Kings 11:18), and of temple and tabernacle functions (Numbers 4:16). God is called episkopos at Job 20:29, referring to His role as Judge, and Christ is an episkopos in 1 Peter 2:25 (RSV: “Shepherd and Guardian of your souls”).

The Council of Jerusalem (Acts 15:1-29) bears witness to a definite hierarchical, episcopal structure of government in the early Church. St. Peter, the chief elder (the office of pope) of the entire Church (1 Peter 5:1; cf. John 21:15-17), presided and issued the authoritative pronouncement (15:7-11). Then James, bishop of Jerusalem (kind of like the host-mayor of a conference) gives a concurring (Acts 15:14), concluding statement (15:13-29). That James was the sole, “monarchical” bishop of Jerusalem is fairly apparent from Scripture (Acts 12:17; 15:13, 19; 21:18; Galatians 1:19; 2:12). This fact is also attested by the first Christian historian, Eusebius (History of the Church, 7:19).

Much historical and patristic evidence also exists for the bishopric of St. Peter at Rome. No one disputes the fact that St. Clement (d. c.101) was the sole bishop of Rome a little later, or that St. Ignatius (d. c.110) was the bishop at Antioch, starting around 69 A.D. Thus, the “monarchical” bishop is both a biblical concept and an unarguable fact of the early Church. By the time we get to the mid-second century, virtually all historians hold that single bishops led each Christian community.

To all who discharge the ministry of the word it gives the name of bishops.

This is untrue, based on the data compiled above. The bishop occupies a higher office.

Thus Paul, after enjoining Titus to ordain elders in every city, immediately adds, “A bishop must be blameless,” &c. (Tit. 1:5, 7).

Note that Timothy is functioning precisely as a Catholic bishop does, by appointing elders (or priests):

Titus 1:5 . . . appoint elders in every town as I directed you

Thus, Titus is under the authority of Paul, and others are under his authority. That is a three-tiered hierarchical structure, any way one looks at it. Therefore, even if the terms somewhat overlap in the New Testament, as the Church was just beginning, nevertheless we see differentiation in actual duties, which is essentially all that is needed to establish Catholic ecclesiology. Furthermore, Paul appears to be passing on his office to Timothy (1 Tim 6:20; 2 Tim 1:6,13-14; 2 Tim 4:1-6), and tells him to pass his office along, in turn (2 Tim 2:1-2) which would be another indication of apostolic succession in the Bible.

So in another place he salutes several bishops in one church (Phil. 1:1).

But in this passage he mentions “bishops and deacons.” And he is careful to distinguish them elsewhere, since he mentions the qualifications of bishops, specifically, in Titus 1 and 1 Timothy 3:1-7. But then he separately writes about the qualifications for deacons in 1 Timothy 3:8-10. Thus, if he makes this differentiation, it stands to reason that he probably does the same with regard to elders. Also, Paul often referred to himself as a deacon or minister (1 Cor 3:5; 4:1; 2 Cor 3:6; 6:4; 11:23; Eph 3:7; Col 1:23-25), yet no one would say he was merely a deacon.

And in the Acts, the elders of Ephesus, whom he is said to have called together, he, in the course of his address, designates as bishops (Acts 20:17).

A bishop is a chief elder, just as in the Catholic Church, a bishop is also a priest. He is a sort of super-priest. A bishop can still be called a priest, but priests cannot be called bishops unless they are bishops! And who appoints bishops? The pope does that. But in Calvin’s ecclesiology he have apostles appointing bishops, but their office doesn’t continue (denial of apostolic succession).

Martin Luther made the same error of jumbling up into one big catch-all category, all of these New Testament offices:

On this account I think it follows that we neither can nor ought to give the name priest to those who are in charge of Word and sacrament among the people. The reason they have been called priests is either because of the custom of heathen people or as a vestige of the Jewish nation. The result is greatly injurious to the church. According to the New Testament Scriptures better names would be ministers, deacons, bishops, stewards, presbyters (a name often used and indicating the older members). For thus Paul writes in I Cor. 4 [:1], “This is how one should regard us, as servants of Christ and stewards of the mysteries of God.” He does not say, “as priests of Christ,” because he knew that the name and office of priest belonged to all. Paul’s frequent use of the word “stewardship” or “household,” “ministry,” “minister,” “servant,” “one serving the gospel,” etc., emphasizes that it is not the estate, or order, or any authority or dignity that he wants to uphold, but only the office and the function. The authority and the dignity of the priesthood resided in the community of believers. (Luther’s Works, Vol. 40: Church and Ministry II, edited by Conrad Bergendoff, Philadephia: Muhlenberg Press, 1958, p. 35; primary work: Concerning the Ministry, 1523, translated by Conrad Bergendoff; my italics)

Government is absolutely necessary, but so are hierarchy, monarchical bishops over geographical areas, a papacy, councils, priests, and apostolic succession: all of which Calvin rejected.

The third division which we have adopted is, by whom ministers are to be chosen. A certain rule on this head cannot be obtained from the appointment of the apostles, which was somewhat different from the common call of others. As theirs was an extraordinary ministry, in order to render it conspicuous by some more distinguished mark, those who were to discharge it behoved to be called and appointed by the mouth of the Lord himself. It was not, therefore, by any human election, but at the sole command of God and Christ, that they prepared themselves for the work.

This was manifestly not true in Paul’s case. In his very conversion experience, Jesus informed Paul that he would be told what to do (Acts 9:6; cf. 9:17). He went to see St. Peter in Jerusalem for fifteen days in order to be confirmed in his calling (Galatians 1:18), and fourteen years later was commissioned by Peter, James, and John (Galatians 2:1-2, 9). He was also sent out by the Church at Antioch (Acts 13:1-4), which was in contact with the Church at Jerusalem (Acts 11:19-27).

All of this scarcely suggests of Paul (an apostle), Calvin’s description:

It was not, therefore, by any human election, but at the sole command of God and Christ, that they prepared themselves for the work.

St. Paul was called by God but also called and confirmed and sent and directed by men.

Hence, when the apostles were desirous to substitute another in the place of Judas, they did not venture to nominate any one certainly, but brought forward two, that the Lord might declare by lot which of them he wished to succeed (Acts 1:23).

This demonstrates apostolic succession in the Bible. Yet Calvin rejects that notion, as historically always understood.

In this way we ought to understand Paul’s declaration, that he was made an apostle, “not of men, neither by man, but by Jesus Christ, and God the Father” (Gal. 1:1). The former—viz. not of men—he had in common with all the pious ministers of the word, for no one could duly perform the office unless called by God.

In his initial calling, yes, this is true. But this doesn’t mean that he was some “lone ranger”: not in submission to the Church, as has been amply shown.

The other was proper and peculiar to him. And while he glories in it, he boasts that he had not only what pertains to a true and lawful pastor, but he also brings forward the insignia of his apostleship. For when there were some among the Galatians who, seeking to disparage his authority, represented him as some ordinary disciple, substituted in place of the primary apostles, he, in order to maintain unimpaired the dignity of his ministry, against which he knew that these attempts were made, felt it necessary to show that he was in no respect inferior to the other apostles. Accordingly, he affirms that he was not chosen by the judgment of men, like some ordinary bishop, but by the mouth and manifest oracle of the Lord himself.

This incorrectly excludes all the human elements of authority and calling, even in Paul’s case, as outlined above. Calvin apparently just sees here what he wants to see. And perhaps this sort of reasoning is how he ultimately justifies his own prominent position in early Protestantism. God alone called him; therefore he couldn’t be properly opposed by anyone, and all who do are God’s enemies (precisely as Luther also thought of himself). Quite convenient . . .

***

(originally 5-20-09)

Photo credit: Historical mixed media figure of John Calvin produced by artist/historian George S. Stuart and photographed by Peter d’Aprix: from the George S. Stuart Gallery of Historical Figures archive [Wikimedia Commons / Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license]

***