This is an installment of a series of replies (see the Introduction and Master List) to much of Book IV (Of the Holy Catholic Church) of Institutes of the Christian Religion, by early Protestant leader John Calvin (1509-1564). I utilize the public domain translation of Henry Beveridge, dated 1845, from the 1559 edition in Latin; available online. Calvin’s words will be in blue. All biblical citations (in my portions) will be from RSV unless otherwise noted.

Related reading from yours truly:

Biblical Catholic Answers for John Calvin (2010 book: 388 pages)

A Biblical Critique of Calvinism (2012 book: 178 pages)

Biblical Catholic Salvation: “Faith Working Through Love” (2010 book: 187 pages; includes biblical critiques of all five points of “TULIP”)

*****

IV, 2:6-9

***

CHAPTER 2.

COMPARISON BETWEEN THE FALSE CHURCH AND THE TRUE.

Cyprian, also, following Paul, derives the fountain of ecclesiastical concord from the one bishopric of Christ, and afterwards adds, “There is one Church, which by increase from fecundity is more widely extended to a multitude, just as there are many rays of the sun, but one light, and many branches of a tree, but one trunk upheld by the tenacious root. When many streams flow from one fountain, though there seems wide spreading numerosity from the overflowing copiousness of the supply, yet unity remains in the origin. Pluck a ray from the body of the sun, and the unity sustains no division. Break a branch from a tree, and the branch will not germinate. Cut off a stream from a fountain, that which is thus cut off dries up. So the Church, pervaded by the light of the Lord, extends over the whole globe, and yet the light which is everywhere diffused is one” (Cyprian, de Simplicit. Prælat.).

Amen! But Calvin wants to co-opt St. Cyprian for his own ends of claiming that the Church can be defined in a way that excludes the Catholic Church headed by the pope of Rome, as its very center and foundation. This won’t fly, once we consult other statements from the same father (that Calvin somehow overlooked):

The Lord speaks to Peter, saying, “I say unto thee, that thou art Peter; and upon this rock I will build my Church, and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it. And I will give unto thee the keys of the kingdom of heaven; and whatsoever thou shalt bind on earth shall be bound also in heaven, and whatsoever thou shalt loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven.” And again to the same He says, after His resurrection, “Feed my sheep.” And although to all the apostles, after His resurrection, He gives an equal power, and says, “As the Father hath sent me, even so send I you: Receive ye the Holy Ghost: Whose soever sins ye remit, they shall be remitted unto him; and whose soever sins ye retain, they shall be retained;” yet, that He might set forth unity, He arranged by His authority the origin of that unity, as beginning from one. Assuredly the rest of the apostles were also the same as was Peter, endowed with a like partnership both of honour and power; but the beginning proceeds from unity. (The Unity of the Church [Treatise IV]; ANF, Vol. V)

Nevertheless, Peter, upon whom by the same Lord the Church had been built, speaking one for all, and answering with the voice of the Church, says, “Lord, to whom shall we go? Thou hast the words of eternal life; and we believe, and are sure that Thou art the Christ, the Son of the living God:” signifying, doubtless, and showing that those who departed from Christ perished by their own fault, yet that the Church which believes on Christ, and holds that which it has once learned, never departs from Him at all, and that those are the Church who remain in the house of God; . . . After such things as these, moreover, they still dare—a false bishop having been appointed for them by heretics—to set sail and to bear letters from schismatic and profane persons to the throne of Peter, and to the chief church whence priestly unity takes its source; and not to consider that these were the Romans whose faith was praised in the preaching of the apostle, to whom faithlessness could have no access. (Epistle LIV [LIX], To Cornelius, Concerning Fortunatus and Felicissimus, 7, 14; ANF, Vol. V)

They who have not peace themselves now offer peace to others. They who have withdrawn from the Church promise to lead back and to recall the lapsed to the Church. There is one God and one Christ, and one Church, and one Chair founded on Peter by the word of the Lord. It is not possible to set up another altar or for there to be another priesthood besides that one altar and that one priesthood. Whoever has gathered elsewhere is scattering. (Letter 43 [40], To All His People, 5; in William A. Jurgens, editor and translator, The Faith of the Early Fathers, volume I [of 3], Collegeville, Minnesota: Liturgical Press, 1970, 229)

There speaks Peter, upon whom the Church would be built, teaching in the name of the Church and showing that even if a stubborn and proud multitude withdraws because it does not wish to obey, yet the Church does not withdraw from Christ. The people joined to the priest and the flock clinging to their shepherd are the Church. You ought to know, then, that the bishop is in the Church and the Church in the bishop, and if someone is not with the bishop, he is not in the Church. They vainly flatter themselves who creep up, not having peace with the priests of God, believing that they are secretly in communion with certain individuals. For the Church, which is One and Catholic, is not split nor divided, but is indeed united and joined by the cement of priests who adhere one to another.” (Letter 66 [69], 8; To Florentius Pupianus; in Jurgens, vol. I, 233-234)

St. Cyprian believed that Rome and the pope were the final arbiters of orthodoxy in the Church. That is Catholic authority: the very thing which Calvin pretends the Church can do without. But Calvin pretends that Cyprian appealed only to Christ and not also to St. Peter and his successors, the popes. Thus, he wrongly appeals to St. Cyprian on behalf of false views of ecclesiology that the saint would never have sanctioned.

This is what is called “anachronistic [or highly selective and partial] citation of the Church fathers.” Calvin was a master of that, and so are many of his followers today. And we shall point out when he does it, every time we run across it. Critiques and counter-arguments are wonderful teaching tools indeed.

Words could not more elegantly express the inseparable connection which all the members of Christ have with each other.

They sure do, and this includes historical and institutional and doctrinal unity (and real, binding Church authority) as well as abstract, “metaphysical” or “lowest common denominator” unity.

We see how he constantly calls us back to the head. Accordingly, he declares that when heresies and schisms arise, it is because men return not to the origin of the truth, because they seek not the head, because they keep not the doctrine of the heavenly Master. Let them now go and clamour against us as heretics for having withdrawn from their Church, since the only cause of our estrangement is, that they cannot tolerate a pure profession of the truth.

Empty, unsubstantiated rhetoric . . . all the heretics of history spoke like this.

I say nothing of their having expelled us by anathemas and curses. The fact is more than sufficient to excuse us, unless they would also make schismatics of the apostles, with whom we have a common cause.

Calvin begs the question again (which is becoming a very common theme in his writing). Anathemas are quite a biblical thing. And sectarianisim, divisiveness, and denominations are constantly condemned in Holy Scripture, especially by St. Paul.

Christ, I say, forewarned his apostles, “they shall put you out of the synagogues” (John 16:2). The synagogues of which he speaks were then held to be lawful churches. Seeing then it is certain that we were cast out,

Protestants cast themselves out, by refusing to abide by received apostolic tradition and the authority and standard of orthodoxy that had always existed since Christ (not to mention abandonment of vows on the part of most of the Protestant founders). In Luther’s case, for example, he dissented on at least 50 matters of Catholic doctrine before he was ever excommunicated (this was all by the year 1520).

It’s ridiculous to expect any belief system whatever, religious or otherwise, to change fifty of its tenets, simply because one dissident demands that they do so. Therefore, it is absurd for Protestants to act as if they were unfairly tossed out of the Church. They freely chose to leave, by refusing to accept many Catholic teachings.

and we are prepared to show that this was done for the name of Christ, the cause should first be ascertained before any decision is given either for or against us. This, however, if they choose, I am willing to leave to them; to me it is enough that we behoved to withdraw from them in order to draw near to Christ.

And I shall continue to show that Calvin’s grounds for doing so were wholly inadequate and misguided on every level.

David murdered and committed adultery, but that didn’t cause God to withdraw His eternal covenant with him. Catholics readily grant that the ancient Jews were often (usually) corrupt and that they repeatedly fell into rebellion and wickedness. But it is not the case that they ever ceased to be the Chosen People: a precursor of the Church, as we have shown repeatedly in past installments.

For who can presume to deny the title of the Church to those with whom the Lord deposited the preaching of his word and the observance of his mysteries?

We agree. St. Paul argued exactly this in Romans 9:4 and 11:1-5,26-29, as examined already in the previous installment.

On the other hand, who may presume to give the name of Church, without reservation, to that assembly by which the word of God is openly and with impunity trampled under foot—where his ministry, its chief support, and the very soul of the Church, is destroyed?

This is asserted without being proven in the least. I will reply when Calvin offers some semblance of a rational argument. It may never come. If he never offers an argument on this score — only bare, axiomatic assertions — then I have no burden of replying to a non-argument.

No particular disagreement here . . . Calvin is simply recounting the history of the Jews as we know it from the Old Testament.

Now then let the Papists, in order to extenuate their vices as much as possible, deny, if they can, that the state of religion is as much vitiated and corrupted with them as it was in the kingdom of Israel under Jeroboam.

I’m happy to do so, without denying that there was plenty of corruption among individual Catholics in Calvin’s period (as there was among individual Protestants). The doctrine did not become fundamentally corrupted, however, because that was under God’s Protection.

They have a grosser idolatry, and in doctrine are not one whit more pure; rather, perhaps, they are even still more impure. God, nay, even those possessed of a moderate degree of judgment, will bear me witness, and the thing itself is too manifest to require me to enlarge upon it.

How convenient. Calvin in effect says, “my point of view is self-evident; therefore I don’t have to devote any of my energies and considerable zeal to rationally defending it.” That won’t fly.

When they would force us to the communion of their Church,

It is not “their” Church; it is the Church. Calvin’s burden remains: he has to establish that his “church” is the one true Church, and that the Catholic Church is not. He hasn’t come within a universe of doing so thus far. And I confidently predict that he never will.

they make two demands upon us—first, that we join in their prayers, their sacrifices, and all their ceremonies; and, secondly, that whatever honour, power, and jurisdiction, Christ has given to his Church, the same we must attribute to theirs. In regard to the first, I admit that all the prophets who were at Jerusalem, when matters there were very corrupt, neither sacrificed apart nor held separate meetings for prayer. For they had the command of God, which enjoined them to meet in the temple of Solomon, and they knew that the Levitical priests, whom the Lord had appointed over sacred matters, and who were not yet discarded, how unworthy soever they might be of that honour, were still entitled to hold it (Exod. 24:9). But the principal point in the whole question is, that they were not compelled to any superstitious worship, nay, they undertook nothing but what had been instituted by God. But in these men, I mean the Papists, where is the resemblance? Scarcely can we hold any meeting with them without polluting ourselves with open idolatry. Their principal bond of communion is undoubtedly in the Mass, which we abominate as the greatest sacrilege.

If Calvin wants to define the Mass as “open idolatry” and “the greatest sacrilege” why, then, doesn’t he disavow himself from all the Church fathers who believed in faith, in the sacrifice of the Mass? It’s easy for him to rail against Rome; far more difficult to disentangle himself from the mountain of evidence of the Church fathers, who believed the same thing. Calvin doesn’t want to get into that. He wants to act as if the early Church and history is on his side; therefore he only cherry-picks from the fathers what appears to support his dissident view, while ignoring massive amounts of historical patristic facts. No one need take my word or any Catholic’s word on these facts of history. Protestant historians abundantly back up our contentions. For example, Philip Schaff:

The Catholic church, both Greek and Latin, sees in the Eucharist not only a sacramentum, in which God communicates a grace to believers, but at the same time, and in fact mainly, a sacrificium, in which believers really offer to God that which is represented by the sensible elements. For this view also the church fathers laid the foundation, and it must be conceded they stand in general far more on the Greek and Roman Catholic than on the Protestant side of this question. . . . (History of the Christian Church, Vol. III: Nicene and Post-Nicene Christianity: A.D. 311-600, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1974, from the revised fifth edition of 1910; § 96. “The Sacrifice of the Eucharist”)

It was also widely held from the first that the Eucharist is in some sense a sacrifice, though here again definition was gradual. The suggestion of sacrifice is contained in much of the NT language . . . the words of institution, ‘covenant,’ ‘memorial,’ ‘poured out,’ all have sacrificial associations. In early post-NT times the constant repudiation of carnal sacrifice and emphasis on life and prayer at Christian worship did not hinder the Eucharist from being described as a sacrifice from the first . . .

From early times the Eucharistic offering was called a sacrifice in virtue of its immediate relation to the sacrifice of Christ. (F. L. Cross & E. A. Livingstone, The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, 2nd edition, Oxford University Press, 1983, 476, 1221)

[T]he Eucharist was regarded as the distinctively Christian sacrifice from the closing decade of the first century, if not earlier. Malachi’s prediction (1:10 f.) that the Lord would reject the Jewish sacrifices and instead would have ‘a pure offering’ made to Him by the Gentiles in every place was early seized [did. 14,3; Justin, dial. 41,2 f.; Irenaeus, haer. 4,17,5] upon by Christians as a prophecy of the eucharist.

The Didache indeed actually applies [14, 1] the term thusia, or sacrifice, to the eucharist, and the idea is presupposed by Clement in the parallel he discovers [40-4] between the Church’s ministers and the Old Testament priests and levites . . . Ignatius’s reference [Philad. 4] to ‘one altar, just as there is one bishop’, reveals that he, too thought in sacrificial terms. Justin speaks [Dial. 117,1] of ‘all the sacrifices in this name which Jesus appointed to be performed, viz. in the eucharist of the bread and the cup, and which are celebrated in every place by Christians’. Not only here but elsewhere [Ib. 41,3] too, he identifies ‘the bread of the eucharist, and the cup likewise of the eucharist’, with the sacrifice foretold by Malachi. For Irenaeus [Haer. 4,17,5] the eucharist is ‘the new oblation of the new covenant’, . . .

It was natural for early Christians to think of the eucharist as a sacrifice. The fulfillment of prophecy demanded a solemn Christian offering, and the rite itself was wrapped in the sacrificial atmosphere with which our Lord invested the Last Supper. The words of institution, ‘Do this’ (touto poieite), must have been charged with sacrificial overtones for second-century ears; Justin at any rate understood [1 apol. 66,3; cf. dial. 41,1] them to mean, ‘Offer this.’ . . . Justin . . . makes it plain [Dial. 41,3] that the bread and the wine themselves were the ‘pure offering’ foretold by Malachi . . . he uses [1 apol. 65,3-5] the term ‘thanksgiving’ as technically equivalent to ‘the eucharistized bread and wine’. The bread and wine, moreover, are offered ‘for a memorial (eis anamnasin) of the passion,’ a phrase which in view of his identification of them with the Lord’s body and blood implies much more than an act of purely spiritual recollection. Altogether it would seem that, while his language is not fully explicit, Justin is feeling his way to the conception of the eucharist as the offering of the Saviour’s passion. (J. N. D. Kelly, Early Christian Doctrines, San Francisco: Harper & Row, fifth revised edition, 1978. 196-197)

[T]he eucharist was regarded without question as the Christian sacrifice. (Kelly, ibid., 449)

Whether this is justly or rashly done will be elsewhere seen (see chap. 18; see also Book 2, chap. 15, sec. 6)

I look forward to seeing the reasoning Calvin provides in IV, ch. 18.

It is now sufficient to show that our case is different from that of the prophets, who, when they were present at the sacred rites of the ungodly, were not obliged to witness or use any ceremonies but those which were instituted by God. But if we would have an example in all respects similar, let us take one from the kingdom of Israel. Under the ordinance of Jeroboam, circumcision remained, sacrifices were offered, the law was deemed holy, and the God whom they had received from their fathers was worshipped; but in consequence of invented and forbidden modes of worship, everything which was done there God disapproved and condemned. Show me one prophet or pious man who once worshipped or offered sacrifice in Bethel. They knew that they could not do it without defiling themselves with some kind of sacrilege.

Of course, because then the only permitted sacrifice occurred at the Temple in Jerusalem.

We hold, therefore, that the communion of the Church ought not to be carried so far by the godly as to lay them under a necessity of following it when it has degenerated to profane and polluted rites.

Absolutely. Whether this happened in the Catholic Church (and from a very early period: the first century: as Protestant historians show us) remains utterly unproven, despite Calvin’s many flowery, axiomatic, question-begging condemnations.

***

(originally 5-19-09)

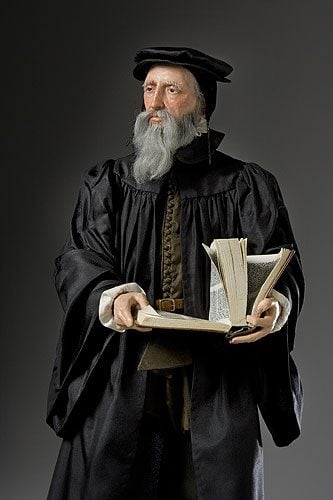

Photo credit: Historical mixed media figure of John Calvin produced by artist/historian George S. Stuart and photographed by Peter d’Aprix: from the George S. Stuart Gallery of Historical Figures archive [Wikimedia Commons / Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license]

***