This is an installment of a series of replies (see the Introduction and Master List) to much of Book IV (Of the Holy Catholic Church) of Institutes of the Christian Religion, by early Protestant leader John Calvin (1509-1564). I utilize the public domain translation of Henry Beveridge, dated 1845, from the 1559 edition in Latin; available online. Calvin’s words will be in blue. All biblical citations (in my portions) will be from RSV unless otherwise noted.

Related reading from yours truly:

Biblical Catholic Answers for John Calvin (2010 book: 388 pages)

A Biblical Critique of Calvinism (2012 book: 178 pages)

Biblical Catholic Salvation: “Faith Working Through Love” (2010 book: 187 pages; includes biblical critiques of all five points of “TULIP”)

*****

IV, 17:3-10

***

CHAPTER 17

To all these things we have a complete attestation in this sacrament, enabling us certainly to conclude that they are as truly exhibited to us as if Christ were placed in bodily presence before our view, or handled by our hands.

Note the “as if” — it dilutes the Real Presence.

For these are words which can never lie nor deceive—Take, eat, drink. This is my body, which is broken for you: this is my blood, which is shed for the remission of sins.

Indeed they cannot: if they are believed and not sophistically watered down and explained away.

In bidding us take, he intimates that it is ours: in bidding us eat, he intimates that it becomes one substance with us: in affirming of his body that it was broken, and of his blood that it was shed for us, he shows that both were not so much his own as ours, because he took and laid down both, not for his own advantage, but for our salvation. And we ought carefully to observe, that the chief, and almost the whole energy of the sacrament, consists in these words, It is broken for you: it is shed for you. It would not be of much importance to us that the body and blood of the Lord are now distributed, had they not once been set forth for our redemption and salvation. Wherefore they are represented under bread and wine, that we may learn that they are not only ours, but intended to nourish our spiritual life; that is, as we formerly observed, by the corporeal things which are produced in the sacrament, we are by a kind of analogy conducted to spiritual things. Thus when bread is given as a symbol of the body of Christ, we must immediately think of this similitude.

The bread and wine is initially symbolic, but when transubstantiation takes place, Jesus is truly physically present under the appearances of bread and wine. That is the step Calvin refuses to take: over against the Bible and the fathers (virtually to a man).

As bread nourishes, sustains, and protects our bodily life, so the body of Christ is the only food to invigorate and keep alive the soul. When we behold wine set forth as a symbol of blood, we must think that such use as wine serves to the body, the same is spiritually bestowed by the blood of Christ;

“Symbol”, “spiritually bestowed” . . . For the Catholic, spiritual realities are not inherently antithetical to physical realities, because for us, the Eucharist is an extension of the Incarnation, which was very much a physical reality.

and the use is to foster, refresh, strengthen, and exhilarate. For if we duly consider what profit we have gained by the breaking of his sacred body, and the shedding of his blood, we shall clearly perceive that these properties of bread and wine, agreeably to this analogy, most appropriately represent it when they are communicated to us.

“Analogy”, “represent” . . . we see the direction of Calvin’s thought. He is far closer to Zwingli’s pure symbolism than to Luther’s traditional eucharistic realism.

Therefore, it is not the principal part of a sacrament simply to hold forth the body of Christ to us without any higher consideration, but rather to seal and confirm that promise by which he testifies that his flesh is meat indeed, and his blood drink indeed, nourishing us unto life eternal, and by which he affirms that he is the bread of life, of which, whosoever shall eat, shall live for ever—I say, to seal and confirm that promise, and in order to do so, it sends us to the cross of Christ, where that promise was performed and fulfilled in all its parts.

Typical Calvin incoherent word games and sophistry: going far beyond what the biblical text teaches us about these matters . . . again, the Eucharist can only “seal and confirm that promise” rather than be the actual Body and Blood of Christ. It’s the same thinking process he applied to baptism. It is no less fallacious in this instance than it was in that one.

For we do not eat Christ duly and savingly unless as crucified, while with lively apprehension we perceive the efficacy of his death.

Obviously the crucifixion is the backdrop of the Eucharist. Catholics and Protestants have no disagreement on that.

When he called himself the bread of life, he did not take that appellation from the sacrament, as some perversely interpret; but such as he was given to us by the Father, such he exhibited himself when becoming partaker of our human mortality, he made us partakers of his divine immortality; when offering himself in sacrifice, he took our curse upon himself, that he might cover us with his blessing, when by his death he devoured and swallowed up death, when in his resurrection he raised our corruptible flesh, which he had put on, to glory and incorruption.

This is all true.

It only remains that the whole become ours by application. This is done by means of the gospel, and more clearly by the sacred Supper, where Christ offers himself to us with all his blessings, and we receive him in faith. The sacrament, therefore, does not make Christ become for the first time the bread of life; but, while it calls to remembrance that Christ was made the bread of life that we may constantly eat him, it gives us a taste and relish for that bread, and makes us feel its efficacy. For it assures us, first, that whatever Christ did or suffered was done to give us life; and, secondly, that this quickening is eternal; by it we are ceaselessly nourished, sustained, and preserved in life.

This is very subtle heretical reasoning: the Eucharist has power not because of what it inherently is: the Body and Blood of Christ, but only because it represents other things that we comprehend in and with faith. Hence, “it calls to remembrance that Christ was made the bread of life.”

For as Christ would not have not been the bread of life to us if he had not been born, if he had not died and risen again; so he could not now be the bread of life, were not the efficacy and fruit of his nativity, death, and resurrection, eternal. All this Christ has elegantly expressed in these words, “The bread that I will give is my flesh, which I will give for the life of the world” (John 6:51); doubtless intimating, that his body will be as bread in regard to the spiritual life of the soul, because it was to be delivered to death for our salvation, and that he extends it to us for food when he makes us partakers of it by faith. Wherefore he once gave himself that he might become bread,

Jesus doesn’t become a piece of bread. This is the absurdity that Calvin’s position actually entails, but that, ironically, Catholics are accused of believing: as if we consciously believe we are worshiping wheat bread rather than Jesus Himself. Because the Calvinist Eucharist remains bread, they then apply the same state of affairs to Catholic worship; therefore, they accuse us of idolatry because we worship Jesus in the Eucharist (whereas they do not, precisely because for them it is not actually the Body and Blood).

But if anything is truly characterized as idolatry, it is the Calvinist position, since the bread never ceases being what it is. Catholics believe that God can be specially present in many different ways: for example, as in the pillars of cloud and fire, or in the ark of the Covenant and Holy of Holies. The Eucharist takes it a step further, in light of the Incarnation, since God has now become man. Calvin doesn’t grasp the new realities that the Incarnation has opened up.

when he gave himself to be crucified for the redemption of the world; and he gives himself daily, when in the word of the gospel he offers himself to be partaken by us, inasmuch as he was crucified, when he seals that offer by the sacred mystery of the Supper, and when he accomplishes inwardly what he externally designates. Moreover, two faults are here to be avoided. We must neither, by setting too little value on the signs, dissever them from their meanings to which they are in some degree annexed, nor by immoderately extolling them, seem somewhat to obscure the mysteries themselves. That Christ is the bread of life by which believers are nourished unto eternal life, no man is so utterly devoid of religion as not to acknowledge. But all are not agreed as to the mode of partaking of him.

Exactly. Some depart from the universal understanding of the Eucharist in the Catholic Church, from Jesus and the apostles until Calvin’s time.

For there are some who define the eating of the flesh of Christ, and the drinking of his blood, to be, in one word, nothing more than believing in Christ himself. But Christ seems to me to have intended to teach something more express and more sublime in that noble discourse, in which he recommends the eating of his flesh—viz. that we are quickened by the true partaking of him, which he designated by the terms eating and drinking, lest any one should suppose that the life which we obtain from him is obtained by simple knowledge. For as it is not the sight but the eating of bread that gives nourishment to the body, so the soul must partake of Christ truly and thoroughly, that by his energy it may grow up into spiritual life.

Here he is describing the purely symbolic position of Zwingli and the Anabaptists (and of many Protestants, including Calvinists, today).

Meanwhile, we admit that this is nothing else than the eating of faith, and that no other eating can be imagined. But there is this difference between their mode of speaking and mine. According to them, to eat is merely to believe; while I maintain that the flesh of Christ is eaten by believing, because it is made ours by faith, and that that eating is the effect and fruit of faith;

Yet it is not the true Body and Blood that are eaten. Is this not, in most major respects, a distinction without a difference? Calvin wants to play word games and draw complicated distinctions, to try to distinguish himself from the Anabaptists and Zwingli on the one hand, and Luther and Catholics, on the other. Yet in the end we are left with his position that the Eucharist does not literally give us Jesus’ Body and Blood, as Jesus Himself plainly says that it does. What we receive is one step removed from actual reality. It has become abstracted and only spiritual (in the non-physical sense).

or, if you will have it more clearly, according to them, eating is faith, whereas it rather seems to me to be a consequence of faith. The difference is little in words, but not little in reality.

No; in fact the difference is little in reality, despite the word games Calvin applies, because there is a “bottom line” and a premise and a presupposition underneath all the flowery, high-sounding, pious rhetoric.

For, although the apostle teaches that Christ dwells in our hearts by faith (Eph. 3:17), no one will interpret that dwelling to be faith. All see that it explains the admirable effect of faith, because to it it is owing that believers have Christ dwelling in them. In this way, the Lord was pleased, by calling himself the bread of life, not only to teach that our salvation is treasured up in the faith of his death and resurrection, but also, by virtue of true communication with him, his life passes into us and becomes ours, just as bread when taken for food gives vigour to the body.

This is true, as far as it goes. It just doesn’t go far enough: to Real Presence and transubstantiation.

When Augustine, whom they claim as their patron, wrote, that we eat by believing, all he meant was to indicate that that eating is of faith, and not of the mouth. This I deny not; but I at the same time add, that by faith we embrace Christ, not as appearing at a distance, but as uniting himself to us, he being our head, and we his members.

And Catholics add that we receive His actual Body and Blood.

I do not absolutely disapprove of that mode of speaking; I only deny that it is a full interpretation, if they mean to define what it is to eat the flesh of Christ.

And we deny in turn that Calvin’s interpretation is the full one. It is tragically incomplete.

I see that Augustine repeatedly used this form of expression, as when he said (De Doct. Christ. Lib. 3), “ Unless ye eat the flesh of the Son of Man” is a figurative expression enjoining us to have communion with our Lord’s passion, and sweetly and usefully to treasure in our memory that his flesh was crucified and wounded for us. Also when he says, “These three thousand men who were converted at the preaching of Peter (Acts 2:41), by believing, drank the blood which they had cruelly shed.” But in very many other passages he admirably commends faith for this, that by means of it our souls are not less refreshed by the communion of the blood of Christ, than our bodies with the bread which they eat.

St. Augustine (unlike Calvin) believed in the Real, Substantial Presence in the Eucharist. I have copiously documented this. He didn’t fall into the illogical “either/or” mentality: pitting sign against reality, as Calvin does.

The very same thing is said by Chrysostom, “Christ makes us his body, not by faith only, but in reality.” He does not mean that we obtain this blessing from any other quarter than from faith: he only intends to prevent any one from thinking of mere imagination when he hears the name of faith.

Yes: he, too, has a realist view that Calvin moves away from, while continuing to semi-dishonestly cite these fathers as on his side (by a selective presentation). Hence, Anglican patristic scholar J. N. D. Kelly writes of St. John Chrysostom:

While admitting that the spiritual gift can be apprehended only by the eyes of the mind and not by sense, Chrysostom exploits the materialist implications of the conversion theory to the full . . . Thus the elements have undergone a change, and Chrysostom describes them as being refashioned or transformed. In the fifth century conversionist views were taken for granted by Alexandrians and Antiochenes alike. . . . [In prod. Iud. hom. I, 6; in Matt. hom. 82, 5] (Early Christian Doctrines, San Francisco: Harper & Row, fifth revised edition, 1978, 443-444)

St. John Chrysostom believed that the bread and wine change into His Body and Blood:

“This is My Body,” he says. This statement transforms the gifts. (Homilies on the Treachery of Judas, 1, 6)

I say nothing of those who hold that the Supper is merely a mark of external profession, because I think I sufficiently refuted their error when I treated of the sacraments in general (Chap. 14 sec. 13). Only let my readers observe, that when the cup is called the covenant in blood (Luke 22:20), the promise which tends to confirm faith is expressed. Hence it follows, that unless we have respect to God, and embrace what he offers, we do not make a right use of the sacred Supper.

That’s correct. We must approach the Lord’s Table in all solemnity, without serious sin on our soul, and believing in the miracle that has taken place.

I am not satisfied with the view of those who, while acknowledging that we have some kind of communion with Christ, only make us partakers of the Spirit, omitting all mention of flesh and blood.

That’s more consistent, I submit, than Calvin “mentioning” flesh and blood, while believing at the same time that they are not really there. At least Zwingli is elegantly simplistic in his heretical error, rather than sophistically convoluted, as Calvin is. From a Catholic perspective, in some ways Calvin’s error is more objectionable than Zwingli’s, because it seems that Calvin should know better than to believe what he does. He’s beholden to mere philosophies and traditions of men, whereas Zwingli is clueless from the outset, and so perhaps can get somewhat of a pass for ignorance.

As if it were said to no purpose at all, that his flesh is meat indeed, and his blood is drink indeed; that we have no life unless we eat that flesh and drink that blood; and so forth.

That’s right. If only Calvin would accept these words at face value . . . He uses them against Zwingli and pure symbolism, yet ironically falls back toward that position himself, more than towards Lutheran and Catholic traditional eucharistic realism.

Therefore, if it is evident that full communion with Christ goes beyond their description, which is too confined, I will attempt briefly to show how far it extends, before proceeding to speak of the contrary vice of excess.

Calvin places himself in the middle, and assumes that this is reasonable. But what Jesus applies to zeal, I would also apply to Calvin’s “moderate” position on the Eucharist:

Revelation 3:15b-16 Would that you were cold or hot! [16] So, because you are lukewarm, and neither cold nor hot, I will spew you out of my mouth.

To follow the analogy: Zwingli is “cold” and the Catholic position is “hot.” Calvin’s view is the “lukewarm” one. It is nothing to glory in.

For I shall have a longer discussion with these hyperbolical doctors, who, according to their gross ideas, fabricate an absurd mode of eating and drinking, and transfigure Christ, after divesting him of his flesh, into a phantom: if, indeed, it be lawful to put this great mystery into words, a mystery which I feel, and therefore freely confess that I am unable to comprehend with my mind, so far am I from wishing any one to measure its sublimity by my feeble capacity.

I would have thought Calvin was describing his own position here. Perhaps a bit of projection . . .

Nay, I rather exhort my readers not to confine their apprehension within those too narrow limits, but to attempt to rise much higher than I can guide them. For whenever this subject is considered, after I have done my utmost, I feel that I have spoken far beneath its dignity.

I can wholeheartedly agree with that!

And though the mind is more powerful in thought than the tongue in expression, it too is overcome and overwhelmed by the magnitude of the subject. All then that remains is to break forth in admiration of the mystery, which it is plain that the mind is inadequate to comprehend, or the tongue to express. I will, however, give a summary of my view as I best can, not doubting its truth, and therefore trusting that it will not be disapproved by pious breasts.

The great mystery and difficulty in understanding the Eucharist for all parties, partially accounts, no doubt, for Calvin’s glaring errors in his own position. But he chose to place himself in a position of authority and to speak dogmatically over against the Catholic tradition. No one forced him at gunpoint to do so. Therefore, he must be held responsible and accountable for the confusion and disbelief that his views caused in others, according to the scriptural injunction:

James 3:1 Let not many of you become teachers, my brethren, for you know that we who teach shall be judged with greater strictness.

First of all, we are taught by the Scriptures that Christ was from the beginning the living Word of the Father, the fountain and origin of life, from which all things should always receive life. Hence John at one time calls him the Word of life, and at another says, that in him was life; intimating, that he, even then pervading all creatures, instilled into them the power of breathing and living. He afterwards adds, that the life was at length manifested, when the Son of God, assuming our nature, exhibited himself in bodily form to be seen and handled. For although he previously diffused his virtue into the creatures, yet as man, because alienated from God by sin,

Jesus was never “alienated from God” because He was God as well as man. This is Nestorian heresy and blasphemy.

had lost the communication of life, and saw death on every side impending over him,

That never happened, either.

he behoved, in order to regain the hope of immortality,

Jesus never lost hope of immortality. He didn’t have to “hope” in it at all (or have “faith” – which is a creaturely attribute, not a divine one), as He already possessed it and knew full well that He did. More Nestorian nonsense and highly deficient Christology . . .

to be restored to the communion of that Word.

Jesus didn’t have to be “restored.”

How little confidence can it give you, to know that the Word of God, from which you are at the greatest distance, contains within himself the fulness of life, whereas in yourself, in whatever direction you turn, you see nothing but death? But ever since that fountain of life began to dwell in our nature, he no longer lies hid at a distance from us, but exhibits himself openly for our participation. Nay, the very flesh in which he resides he makes vivifying to us, that by partaking of it we may feed for immortality. “I,” says he, “am that bread of life;” “I am the living bread which came down from heaven;” “And the bread that I will give is my flesh, which I will give for the life of the world” (John 6:48, 51).

This is correct, but Calvin waters it down and makes his view incoherent by rejecting eucharistic realism.

By these words he declares, not only that he is life, inasmuch as he is the eternal Word of God who came down to us from heaven, but, by coming down, gave vigour to the flesh which he assumed, that a communication of life to us might thence emanate. Hence, too, he adds, that his flesh is meat indeed, and that his blood is drink indeed: by this food believers are reared to eternal life.

One wonders how Calvin can miss the clear meaning in “meat indeed” and “drink indeed”?

The pious, therefore, have admirable comfort in this, that they now find life in their own flesh. For they not only reach it by easy access, but have it spontaneously set forth before them. Let them only throw open the door of their hearts that they may take it into their embrace, and they will obtain it.

Believing in Calvin’s errors will not speed up that process or make it easier.

The flesh of Christ, however, has not such power in itself as to make us live, seeing that by its own first condition it was subject to mortality, and even now, when endued with immortality, lives not by itself. Still it is properly said to be life-giving, as it is pervaded with the fulness of life for the purpose of transmitting it to us.

The first sentence might easily be interpreted as more Nestorianism, but I’ll let that pass and give Calvin the benefit of the doubt, since there is a sense in which some of this is true, and his next sentence is much better. In any event, Scripture asserts that the blood of Christ has an inherent power:

Acts 20:28 Take heed to yourselves and to all the flock, in which the Holy Spirit has made you overseers, to care for the church of God which he obtained with the blood of his own Son.

Romans 3:25 whom God put forward as an expiation by his blood, to be received by faith. . . .

Romans 5:9 Since, therefore, we are now justified by his blood, much more shall we be saved by him from the wrath of God.

Ephesians 1:7 In him we have redemption through his blood, the forgiveness of our trespasses, according to the riches of his grace

Ephesians 2:13 But now in Christ Jesus you who once were far off have been brought near in the blood of Christ.

Colossians 1:20 and through him to reconcile to himself all things, whether on earth or in heaven, making peace by the blood of his cross.

Hebrews 9:11-14 But when Christ appeared as a high priest of the good things that have come, then through the greater and more perfect tent (not made with hands, that is, not of this creation) [12] he entered once for all into the Holy Place, taking not the blood of goats and calves but his own blood, thus securing an eternal redemption. [13] For if the sprinkling of defiled persons with the blood of goats and bulls and with the ashes of a heifer sanctifies for the purification of the flesh, [14] how much more shall the blood of Christ, who through the eternal Spirit offered himself without blemish to God, purify your conscience from dead works to serve the living God.

Hebrews 10:19 Therefore, brethren, since we have confidence to enter the sanctuary by the blood of Jesus,

Hebrews 10:29 How much worse punishment do you think will be deserved by the man who has spurned the Son of God, and profaned the blood of the covenant by which he was sanctified, and outraged the Spirit of grace?

Hebrews 13:12 So Jesus also suffered outside the gate in order to sanctify the people through his own blood.

Hebrews 13:20 Now may the God of peace who brought again from the dead our Lord Jesus, the great shepherd of the sheep, by the blood of the eternal covenant,

1 Peter 1:18-19 You know that you were ransomed from the futile ways inherited from your fathers, not with perishable things such as silver or gold, [19] but with the precious blood of Christ, like that of a lamb without blemish or spot.

1 John 1:7 but if we walk in the light, as he is in the light, we have fellowship with one another, and the blood of Jesus his Son cleanses us from all sin.

Revelation 1:5 and from Jesus Christ the faithful witness, the first-born of the dead, and the ruler of kings on earth. To him who loves us and has freed us from our sins by his blood

Revelation 5:9 and they sang a new song, saying, “Worthy art thou to take the scroll and to open its seals, for thou wast slain and by thy blood didst ransom men for God from every tribe and tongue and people and nation,

Revelation 7:14 I said to him, “Sir, you know.” And he said to me, “These are they who have come out of the great tribulation; they have washed their robes and made them white in the blood of the Lamb.

In a paper about basic Christology, I clarified some matters that may be relevant presently:

The orthodox Catholic notion of communicatio idiomatum holds that:

The human and the divine activities predicated of Christ in Holy Writ and in the Fathers may not be divided between persons or hypostases, the Man-Christ and the God-Logos, but must be attributed to the one Christ, the Logos become Flesh . . . It is the Divine Logos, who suffered in the flesh, was crucified, and rose again . . . (Ludwig Ott, Fundamentals of Catholic Dogma, p. 144)

Christ’s Divine and Human characteristics and activities are to be predicated of the one Word Incarnate. (De fide.)

As Christ’s Divine Person subsists in two natures, and may be referred to either of those two natures, so human things can be asserted of the son of God and Divine things of the Son of Man. (Ott, p. 160)

In this sense I understand our Saviour’s words as Cyril interprets them, “As the Father hath life in himself, so hath he given to the Son to have life in himself” (John 5:26). For there properly he is speaking not of the properties which he possessed with the Father from the beginning, but of those with which he was invested in the flesh in which he appeared. Accordingly, he shows that in his humanity also fulness of life resides, so that every one who communicates in his flesh and blood, at the same time enjoys the participation of life. The nature of this may be explained by a familiar example. As water is at one time drunk out of the fountain, at another drawn, at another led away by conduits to irrigate the fields, and yet does not flow forth of itself for all these uses, but is taken from its source, which, with perennial flow, ever and anon sends forth a new and sufficient supply; so the flesh of Christ is like a rich and inexhaustible fountain, which transfuses into us the life flowing forth from the Godhead into itself. Now, who sees not that the communion of the flesh and blood of Christ is necessary to all who aspire to the heavenly life?

Then why not maintain the biblical realism that is so apparent not only in the eucharistic passages, but also the (semi-eucharistic?) ones about blood above?

Hence those passages of the apostle: The Church is the “body” of Christ; his “fulness.” He is “the head,” “from whence the whole body fitly joined together, and compacted by that which every joint supplieth,” “maketh increase of the body” (Eph. 1:23; 4:15,16). Our bodies are the “members of Christ” (1 Cor. 6:15). We perceive that all these things cannot possibly take place unless he adheres to us wholly in body and spirit.

More realism, which reinforces my overall point . . .

But the very close connection which unites us to his flesh, he illustrated with still more splendid epithets, when he said that we “are members of his body, of his flesh, and of his bones” (Eph. 5:30). At length, to testify that the matter is too high for utterance, he concludes with exclaiming, “This is a great mystery” (Eph. 5:32). It were, therefore, extreme infatuation not to acknowledge the communion of believers with the body and blood of the Lord, a communion which the apostle declares to be so great, that he chooses rather to marvel at it than to explain it.

Just because it is a mystery (not completely grasped by reason alone and requiring much supernatural faith), it doesn’t follow that we have to relegate the whole thing to symbolism or mysticism, rather than literalness and realism. We need not fully understand a thing in order to believe that it is real and not merely symbolic of something else that is real. In other words, lack of full understanding in our reason is no necessity for moving to symbolism, as a way to comprehend the mystery.

That doesn’t follow. We don’t have to place everything in the neat little box of our own making, based on our inadequate comprehension. We can believe, for example, that electricity or light or protons and neutrons and electrons are real things, without fully understanding all the ins and outs of them.

The sum is, that the flesh and blood of Christ feed our souls just as bread and wine maintain and support our corporeal life.

It doesn’t necessarily follow (logically) that the “flesh and blood of Christ” must be received only mystically and immaterially, because our souls are immaterial, which is subtly implied by the comparison above:

Physical food supports a physical body.

Non-physical spiritual food supports non-physical souls.

For there would be no aptitude in the sign, did not our souls find their nourishment in Christ. This could not be, did not Christ truly form one with us, and refresh us by the eating of his flesh, and the drinking of his blood. But though it seems an incredible thing that the flesh of Christ, while at such a distance from us in respect of place, should be food to us,

Here we start to realize how far from the truth of the Eucharist Calvin really is. Note how he separates the flesh of Christ from the Eucharist, by stating that it is in actuality “at such a distance from us in respect of place.” This gets into his notion (which he elaborates later) that Jesus cannot possibly extend His incarnation in a miraculous eucharistic sense; Calvin has Him confined in heaven, as if that is required of a Divine Person Who is omnipresent and omnipotent.

let us remember how far the secret virtue of the Holy Spirit surpasses all our conceptions, and how foolish it is to wish to measure its immensity by our feeble capacity.

And to limit God due to our own lack of understanding of biblical, Christological categories . . .

Therefore, what our mind does not comprehend let faith conceive—viz. that the Spirit truly unites things separated by space.

Why cannot the same Spirit (Who is the Omnipotent God) unite things spatially and physically? Why is one thing considered impossible while the other is possible merely because it is non-material? Calvin arbitrarily limits God. This is a major flaw in his eucharistic theology.

That sacred communion of flesh and blood by which Christ transfuses his life into us, just as if it penetrated our bones and marrow,

It’s the “just as if” which is unnecessary and mistaken. God has the power to actually “penetrate our bones and marrow.” Why would He not do so?

he testifies and seals in the Supper, and that not by presenting a vain or empty sign, but by there exerting an efficacy of the Spirit by which he fulfils what he promises.

Calvin’s ultimately shallow and “lukewarm” middle ground again . . .

And truly the thing there signified he exhibits and offers to all who sit down at that spiritual feast, although it is beneficially received by believers only who receive this great benefit with true faith and heartfelt gratitude.

“Signified” and “spiritual feast” exhibit Calvin’s non-physical mysticism.

For this reason the apostle said, “The cup of blessing which we bless, is it not the communion of the blood of Christ? The bread which we break, is it not the communion of the body of Christ”? (1 Cor. 10:16.) There is no ground to object that the expression is figurative, and gives the sign the name of the thing signified. I admit, indeed, that the breaking of bread is a symbol, not the reality.

And here we see Calvin’s blind refusal to accept the text at face value. How much clearer could St. Paul be? What else could he say to get across that he intended literal realism and equation of the Eucharist with the Body and Blood of Christ? Why are these words not sufficient? Yet Calvin (astonishingly) redefines Paul’s rather obvious meaning. At some point this must be accounted for. Why does Calvin think in this way?

My theory through the years has been to posit a certain antipathy to matter as inferior to spirit (hearkening back to the Docetic heresy and the pagan Greek philosophy that also led to Gnosticism): an aversion to sacramentalism, and ultimately an insufficient understanding of the import of the Incarnation, which lies behind eucharistic sacramentalism. If one looks down on matter as inferior, then one will tend to reduce physical sacraments to mere symbolism or only a little less objectionable mysticism, or to discard them altogether. And this antipathy extends to a rejection of things like the Sacrifice of the Mass and relics as well.

But this being admitted, we duly infer from the exhibition of the symbol that the thing itself is exhibited. For unless we would charge God with deceit, we will never presume to say that he holds forth an empty symbol.

Nor a symbol, empty or not, when He intends physical presence.

Therefore, if by the breaking of bread the Lord truly represents the partaking of his body,

Not “represents” only, but “presents”.

there ought to be no doubt whatever that he truly exhibits and performs it. The rule which the pious ought always to observe is, whenever they see the symbols instituted by the Lord, to think and feel surely persuaded that the truth of the thing signified is also present.

It is truly disconcerting to see Calvin assert the same basic and unscriptural category errors over and over. He is beholden to some false traditions of men in this regard.

For why does the Lord put the symbol of his body into your hands, but just to assure you that you truly partake of him?

Why indeed would He do that when He has the power to actually give us Himself in a tangible, physical way?

If this is true let us feel as much assured that the visible sign is given us in seal of an invisible gift as that his body itself is given to us.

I would also suggest that there is a certain lack of faith exhibited in these errors. Calvin doesn’t have enough faith to believe that God could become physically present Body, Blood, Soul, and Divinity in what was once bread and wine. It takes a lot of faith to believe that, and Calvin and his followers lack it for some reason. False teaching, therefore, has the sad effect of lessening the faith of its adherents, and making them less aware of supernatural realities that they might otherwise be open to, but for the inculcation of false teachings and misguided category mistakes.

(originally 11-24-09)

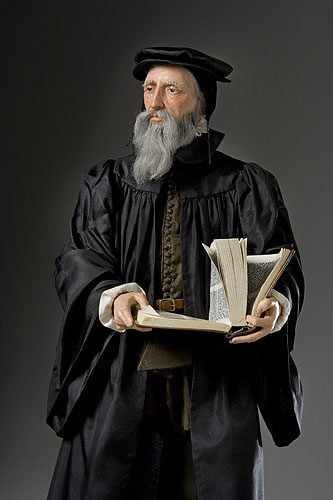

Photo credit: Historical mixed media figure of John Calvin produced by artist/historian George S. Stuart and photographed by Peter d’Aprix: from the George S. Stuart Gallery of Historical Figures archive [Wikimedia Commons / Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license]

***