This is an installment of a series of replies (see the Introduction and Master List) to much of Book IV (Of the Holy Catholic Church) of Institutes of the Christian Religion, by early Protestant leader John Calvin (1509-1564). I utilize the public domain translation of Henry Beveridge, dated 1845, from the 1559 edition in Latin; available online. Calvin’s words will be in blue. All biblical citations (in my portions) will be from RSV unless otherwise noted.

Related reading from yours truly:

Biblical Catholic Answers for John Calvin (2010 book: 388 pages)

A Biblical Critique of Calvinism (2012 book: 178 pages)

Biblical Catholic Salvation: “Faith Working Through Love” (2010 book: 187 pages; includes biblical critiques of all five points of “TULIP”)

*****

IV, 7:12-13

***

CHAPTER 7

In the time of Gregory, that ancient rule was greatly changed. For when the empire was convulsed and torn, when France and Spain were suffering from the many disasters which they ever and anon received, when Illyricum was laid waste, Italy harassed, and Africa almost destroyed by uninterrupted calamities, in order that, during these civil convulsions, the integrity of the faith might remain, or at least not entirely perish, the bishops in all quarters attached themselves more to the Roman Pontiff.

That had already been the pattern for almost 600 years. Nothing had changed. But opponents of the papacy want to overlook scores of confirming evidences for this and claim historical happenstance and coincidence as the cause of papal supremacy. The incoherence of the anti-papal case is seen in the contradictory claims made by various Protestants: the papacy supposedly began in 313 with Constantine and legalization of Christianity in the Roman Empire, or with Leo the Great in the mid-5th century, or Gregory the Great in the late 6th century, etc. It’s all arbitrary. In fact it was a steady, continuous development from the beginning; grounded in the clear Petrine primacy expressed in Holy Scripture.

In this way, not only the dignity, but also the power of the see, exceedingly increased,

So in Calvin’s take the time of Gregory saw an increase by leaps and bounds. Others would place this phenomenon in Leo’s reign, some 140 years before.

although I attach no great importance to the means by which this was accomplished. It is certain, that it was then greater than in former ages.

Calvin’s power to dogmatically declare his own anti-traditional Calvinist doctrines and dogmas (as in the very book here under consideration) was certainly far greater than any pope’s power ever. At least popes are constrained by the received traditions. They have neither power nor jurisdiction to change apostolic doctrine, passed down faithfully for centuries.

Calvin, on the other hand, can ditch and dispense of apostolic traditions in one day, with the stroke of a pen. This renders rather ironic and absurdly comic, his critiques of papal authority. The same criticism applies to Luther, Zwingli, and Henry VIII, as well as the leaders of the Anabaptists, who were even more radically anti-traditional than these men.

And yet it was very different from the unbridled dominion of one ruling others as he pleased.

Thanks for small favors . . .

Still the reverence paid to the Roman See was such, that by its authority it could guide and repress those whom their own colleagues were unable to keep to their duty; for Gregory is careful ever and anon to testify that he was not less faithful in preserving the rights of others, that in insisting that his own should be preserved. “I do not,” says he, “under the stimulus of ambition, derogate from any man’s right, but desire to honour my brethren in all things” (Gregor. Lib. 2 Ep. 68). There is no sentence in his writings in which he boasts more proudly of the extent of his primacy than the following: “I know not what bishop is not subject to the Roman See, when he is discovered in a fault” (Leo. Lib. 2, Epist. 68). However, he immediately adds, “Where faults do not call for interference, all are equal according to the rule of humility.” He claims for himself the right of correcting those who have sinned; if all do their duty, he puts himself on a footing of equality.

Well, sure. If there is no need for papal intervention, then, practically speaking, they are fellow bishops. This is practical common sense. But it doesn’t override the essential hierarchical structure of the system, with the pope on top. But Gregory the Great asserted more for papal authority than Calvin would have it:

Inasmuch as it is manifest that the Apostolic See, is, by the ordering of God, set over all Churches, there is, among our manifold cares, especial demand for our attention . . . (Letter to Subdeacon John; Register of the Epistles, Book III, Epistle 30; NPNF 2, Vol. XII)

Yet I exhort thee that, as long as some time of life remains for thee, thy soul may not be found to be divided from the church of the same blessed Peter, to whom the keys of the heavenly kingdom were entrusted and the power of binding and loosing was granted, lest if his benefit be despised down here, he may close up the entrance to life up there. (The Great Epistles, B IV, Ep. 41), in J. P. Migne, Patr. Lat., translated by John Collorafi)

He, indeed, claimed this right, and those who chose assented to it, while those who were not pleased with it were at liberty to object with impunity; and it is known that the greater part did so. We may add, that he is then speaking of the primate of Byzantium, who, when condemned by a provincial synod, repudiated the whole judgment.

Patriarchs in the east often did so, but in so doing, they usually had already adopted a heretical Christology (so that this is hardly a legitimate argument against papal supremacy and orthodoxy: that Christological heretics dissented from it).

His colleagues had informed the Emperor of his contumacy, and the Emperor had given the cognisance of the matter to Gregory. We see, therefore, that he does not interfere in any way with the ordinary jurisdiction, and that, in acting as a subsidiary to others, he acts entirely by the Emperor’s command.

Emperors often usurped their jurisdiction as well. So did the first Protestants, who replaced the jurisdiction of Rome and the popes with multiple small fiefdoms. Protestant historian Philip Schaff provides the larger picture of what occurred:

Instead of one organization, we have in Protestantism a number of distinct national churches and confessions or denominations. Rome, the local centre of unity, was replaced by Wittenberg, Zurich, Geneva, Oxford, Cambridge, Edinburgh. The one great pope had to surrender to many little popes of smaller pretensions, yet each claiming and exercising sovereign power in his domain. The hierarchical rule gave way to the caesaropapal or Erastian principle, that the owner of the territory is also the owner of its religion (cujus regio, ejus religio), a principle first maintained by the Byzantine Emperors, and held also by the Czar of Russia, but in subjection to the supreme authority of the oecumenical Councils. Every king, prince, and magistrate, who adopted the Reformation, assumed the ecclesiastical supremacy or summepiscopate, and established a national church to the exclusion of Dissenters or Nonconformists who were either expelled, or simply tolerated under various restrictions and disabilities.

Hence there are as many national or state churches as there are independent Protestant governments; but all acknowledge the supremacy of the Scriptures as a rule of faith and practice, and most of them also the evangelical confessions as a correct summary of Scripture doctrines. Every little principality in monarchical Germany and every canton in republican Switzerland has its own church establishment, and claims sovereign power to regulate its creed worship, and discipline. And this power culminates not in the clergy, but in the secular ruler who appoints the ministers of religion and the professors of theology. The property of the church which had accumulated by the pious foundations of the Middle Ages, was secularized during the Reformation period and placed under the control of the state, which in turn assumed the temporal support of the church.

This is the state of things in Europe to this day, except in the independent or free churches of more recent growth, which manage their own affairs on the voluntary principle.

The transfer of the episcopal and papal power to the head of the state was not contemplated by the Reformers, but was the inevitable consequence of the determined opposition of the whole Roman hierarchy to the Reformation. The many and crying abuses which followed this change in the hands of selfish and rapacious princes, were deeply deplored by Melanchthon, who would have consented to the restoration of the episcopal hierarchy on condition of the freedom of gospel preaching and gospel teaching.

The Reformed church in Switzerland secured at first a greater degree of independence than the Lutheran; for Zwingli controlled the magistrate of Zurich, and Calvin ruled supreme in Geneva under institutions of his own founding; but both closely united the civil and ecclesiastical power, and the former gradually assumed the supremacy.

Scandinavia and England adopted, together with the Reformation, a Protestant episcopate which divides the ecclesiastical supremacy with the head of the state; yet even there the civil ruler is legally the supreme governor of the church. (History of the Christian Church, Vol. VII: Modern Christianity. The German Reformation. § 10. Protestantism and Denominationalism)

Is this a vast improvement over the apostolic, patristic, and medieval Catholic ecclesiology? I think not, and the subsequent history of Protestantism amply proves that it is not. Note the clinical and detached way in which Schaff describes wholesale theft of Catholic property: “The property of the church which had accumulated by the pious foundations of the Middle Ages, was secularized during the Reformation period.” Calvin and Luther both sanctioned this immoral activity. One would think that Protestants and Catholics could at least agree that stealing (condemned by the Ten Commandments) was gravely sinful, but this is not the case.

Like the Communists four centuries later, and the pro-abortionists of today, they simply redefined their sinful activities. In this instance, good old-fashioned theft becomes “secularizing” of property. How convenient . . . The first Protestants chose to steal Catholic church properties rather than to trouble themselves to build their own churches. This is all a matter of indisputable historical record.

The Continental “Reformation” was largely achieved and spread by stealing and the power of princes (who even Schaff freely concedes — and Melanchthon lamented — as “selfish and rapacious”), and in England it came about by wholesale murder and the force of law, on pain of death for any dissenters, against the will of (as Hilaire Belloc estimates), at least 80% of the people. And all of this is supposed to be some huge, unmixed improvement over the state of affairs under the papacy, which even Calvin admits was “very different from the unbridled dominion of one ruling others as he pleased”?

13. Even the extent of jurisdiction, thus voluntarily conferred, objected to by Gregory as interfering with better duties.

At this time, therefore, the whole power of the Roman Bishop consisted in opposing stubborn and ungovernable spirits, where some extraordinary remedy was required, and this in order to assist other bishops, not to interfere with them. Therefore, he assumes no more power over others than he elsewhere gives others over himself, when he confesses that he is ready to be corrected by all, amended by all (Lib. 2 Ep. 37).

If Calvin is referring to the epistle of this same number available now on the Internet, I fail to see that what he claims is found in it. What is present throughout the letter is the assumption of Roman and papal supremacy. Here it is in its entirety:

Book II, Letter 37

To John, Bishop of Squillacium (Squillace, in Calabria).

Gregory to John, etc.

The care of our pastoral office warns us to appoint for bereaved churches bishops of their own, who may govern the Lord’s flock with pastoral solicitude. Accordingly we have held it necessary to appoint you, John, bishop of the civitas Lissitana (Lissus, hodie, Alessio?), which has been captured by the enemy, to be cardinal in the Church of Squillacium, that you may carry on the cure of souls once undertaken by you, having regard to future retribution. And although, being driven from your own Church by the invading enemy, you must govern another Church which is now without a shepherd, yet it must be on condition that, in case of the former city being set free from the enemy, and under the protection of God restored to its former state, thou return to the Church in which you were first ordained. If, however, the aforesaid city continues to suffer under the calamity of captivity, you must remain in this Church wherein you are by us incardinated.

Moreover, we enjoin you never to make unlawful ordinations, or allow any bigamist, or one who has taken a wife who was not a virgin, or one ignorant of letters, or one maimed in any part of his body, or a penitent, or one liable to any condition of service, to attain to sacred orders. And, should you find any of this kind, you must not dare to advance them. Africans generally, and unknown strangers, applying for ecclesiastical orders, on no account accept seeing that some Africans are Manichæans, and some have been rebaptized; while many strangers, though being in minor orders, are proved to have pretended to a higher dignity. We also admonish your Fraternity to watch wisely over the souls committed to you, and to be more intent on winning souls than on the profits of the present life. Be diligent in keeping and disposing of the goods of the Church, that the coming Judge, when He comes to judge, may approve you as having in all respects worthily executed the office of shepherd which you have taken upon you. (NPNF 2, Vol. XII)

Another letter in the same book (Epistle 52, to Natalis, Bishop of Salona; a city located in what is now Croatia) is hardly consistent with the picture Calvin wishes to paint (Gregory casually assumes and asserts his superior, preeminent rank):

Now as to your declaring that you cannot possibly be ignorant of the degrees of ecclesiastical rank, I too fully know them with regard to you; and I am therefore much distressed that, if you knew the order of things, you have failed, to your greater blame, in knowing it with regard to me. For, after letters had been addressed to your Blessedness by my predecessor and myself in the cause of the archdeacon Honoratus, then, the sentence of both of us being set at nought, the said Honoratus was deprived of the rank belonging to him. Which thing if any one of the four patriarchs had done, such great contumacy could by no means have been allowed to pass without the most grievous offense. Nevertheless, now that your Fraternity has returned to your proper position, I do not bear in mind the wrong done either to myself or to my predecessor.

So, in another place, though he orders the Bishop of Aquileia to come to Rome to plead his cause in a controversy as to doctrine which had arisen between himself and others, he thus orders not of his own authority, but in obedience to the Emperor’s command. Nor does he declare that he himself will be sole judge, but promises to call a synod, by which the whole business may be determined. But although the moderation was still such, that the power of the Roman See had certain limits which it was not permitted to overstep, and the Roman Bishop himself was not more above than under others, it appears how much Gregory was dissatisfied with this state of matters. For he ever and anon complains, that he, under the colour of the episcopate, was brought back to the world, and was more involved in earthly cares than when living as a laic; that he, in that honourable office, was oppressed by the tumult of secular affairs. Elsewhere he says, “So many burdensome occupations depress me, that my mind cannot at all rise to things above. I am shaken by the many billows of causes, and after they are quieted, am afflicted by the tempests of a tumultuous life, so that I may truly say I am come into the depths of the sea, and the flood has overwhelmed me.” From this I infer what he would have said if he had fallen on the present times. If he did not fulfil, he at least did the duty of a pastor. He declined the administration of civil power, and acknowledged himself subject, like others, to the Emperor. He did not interfere with the management of other churches, unless forced by necessity. And yet he thinks himself in a labyrinth, because he cannot devote himself entirely to the duty of a bishop.

I don’t know how Calvin arrives at these conclusions: all in the direction of minimizing Gregory’s supremacy of jurisdiction as pope. The record has abundant evidences contradictory to Calvin’s (mostly undocumented) assertions. For example, an article in This Rock (December 1992) provides many examples of Gregory’s papal power:

Gregory demonstrated this in his actions. He made it his business to approve candidates for the office of bishop. He rigorously examined men proposed for bishop and, rejecting some as unsuitable for the job, ordered that others be nominated instead (Epistles 1:55, 56; 7:38; 10:7). This is hardly behavior one would expect from a pope who renounced the idea of his having jurisdiction over other bishops.

Like his predecessors and successors, Gregory promulgated numerous laws, binding on all other bishops, on issues such as clerical celibacy (1:42, 50; 4:5, 26, 34; 7:1; 9:110, 218; 10:19; 11:56), the deprivation of priests and bishops guilty of criminal offenses (1:18, 32; 3:49; 4:26; 5:5, 17, 18), and the proper disposition of church revenues (1:10, 64; 2:20–22; 3:22; 4:11).

His Epistle 37 to Emperor Maurice, from Book V leaves no doubt whatever on the matter:

To all who know the Gospel it is obvious that by the voice of the Lord the care of the entire church was committed to the holy apostle and prince of all the apostles, Peter . . . Behold, he received the keys of the kingdom of heaven, the power to bind and loose was given to him, and the care and principality of the entire church was committed to him . . . Am I defending my own cause in this matter? Am I vindicating some special injury of my own? Is it not rather the cause of Almighty God, the cause of the universal church? . . . And we certainly know that many priests of the church of Constantinople have fallen into the whirlpool of heresy and have become not only heretics but heresiarchs . . . Certainly, in honor of Peter, the prince of the apostles, ‘the title ‘universal’] was offered to the Roman pontiff by the venerable Council of Chalcedon. (from Monumenta Germaniae historica: Epistolae; Berlin: 1891 – , Vol. I, 321-322; cited in Jaroslav Pelikan, The Emergence of the Catholic Tradition (100-600), University of Chicago Press, 1971, 352)

Other similar statements nail down the “papal case”:

[T]he prelates of this apostolic see, which by the providence of God I serve, had the honor offered to them of being called ‘universal’ by the venerable Council of Chalcedon.” (Book V, Epistle 44; from Monumenta Germaniae historica: Epistolae; Berlin: 1891 – , Vol. I, 341; cited in Pelikan, ibid., 354)

[W]ho would doubt that it [the church of Constantinople] has been made subject to the apostolic see . . . (Book IX, Epistle 26; from Monumenta Germaniae historica: Epistolae; Berlin: 1891 – , Vol. II, 60; cited in Pelikan, ibid., 354)

[W]ithout the authority and the cobsent of the apostolic see, none of the matters transacted [by a council] have any binding force. (Book IX, Epistle 156; from Monumenta Germaniae historica: Epistolae; Berlin: 1891 – , Vol.II, 158; cited in Pelikan, ibid., 354)

Sentiments like this from Gregory the Great led Jaroslav Pelikan (Lutheran at the time of writing and later Orthodox), in the same work, to declare:

Although earlier pontiffs, notably Leo I, had set forth much of the content of the doctrine of papal primacy and authority, , there is probably no exaggeration in the conventional view, which sees the teaching and practice of Gregory I as the significant turning point for the papacy, not only jurisdictionally but also theologically. In the course of exercising his office he established the doctrinal foundation for his administrative decisions, and in one of his letters [V, 37] he summarized the doctrine . . . (Ibid., 352)

Since the late Dr. Pelikan was not a Catholic, he cannot be accused of Catholic bias in concluding this, whereas on the other hand it is in Calvin’s interest — and constantly manifest in his method — to emphasize only that which supports (or sophistically merely appears to support) the case he wishes to make, with the corresponding suppression of inconvenient evidence that runs contrary to his novel theses.

(originally 6-25-09)

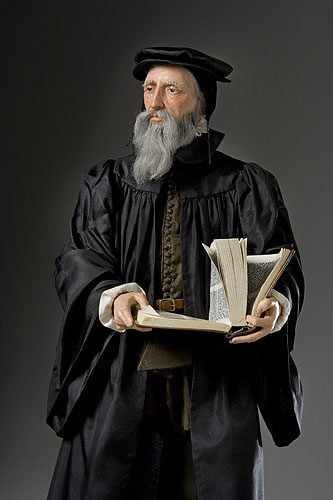

Photo credit: Historical mixed media figure of John Calvin produced by artist/historian George S. Stuart and photographed by Peter d’Aprix: from the George S. Stuart Gallery of Historical Figures archive [Wikimedia Commons / Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license]

***