This is an installment of a series of replies (see the Introduction and Master List) to much of Book IV (Of the Holy Catholic Church) of Institutes of the Christian Religion, by early Protestant leader John Calvin (1509-1564). I utilize the public domain translation of Henry Beveridge, dated 1845, from the 1559 edition in Latin; available online. Calvin’s words will be in blue. All biblical citations (in my portions) will be from RSV unless otherwise noted.

Related reading from yours truly:

Biblical Catholic Answers for John Calvin (2010 book: 388 pages)

A Biblical Critique of Calvinism (2012 book: 178 pages)

Biblical Catholic Salvation: “Faith Working Through Love” (2010 book: 187 pages; includes biblical critiques of all five points of “TULIP”)

*****

IV, 6:15-17

***

CHAPTER 6

*

Paul is afterwards conveyed as a prisoner to Rome. Luke relates that he was received by the brethren, but says nothing of Peter. From Rome he writes to many churches. He even sends salutations from certain individuals, but does not by a single word intimate that Peter was then there. Who, pray, will believe that he would have said nothing of him if he had been present?

Whatever the chronology is, in any event, the consensus of virtually all scholars and biblical commentators is that Peter died in Rome, and probably most agree that he was bishop there. The footnotes for this section state that Calvin accepted the fact that Peter died at Rome, but not that he was the bishop.

Nay, in the Epistle to the Philippians, after saying that he had no one who cared for the work of the Lord so faithfully as Timothy, he complains, that “all seek their own” (Phil. 2:21). And to Timothy he makes the more grievous complaint, that no man was present at his first defence, that all men forsook him (2 Tim. 4:16). Where then was Peter? If they say that he was at Rome, how disgraceful the charge which Paul brings against him of being a deserter of the Gospel! For he is speaking of believers, since he adds, “The Lord lay it not to their charge.” At what time, therefore, and how long, did Peter hold that See? The uniform opinion of authors is, that he governed that church until his death. But these authors are not agreed as to who was his successor. Some say Linus, others Clement. And they relate many absurd fables concerning a discussion between him and Simon Magus. Nor does Augustine, when treating of superstition, disguise the fact, that owing to an opinion rashly entertained, it had become customary at Rome to fast on the day on which Peter carried away the palm from Simon Magus (August. ad Januar. Ep. 2). In short, the affairs of that period are so involved from the variety of opinions, that credit is not to be given rashly to anything we read concerning it. And yet, from this agreement of authors, I do not dispute that he died there, but that he was bishop, particularly for a long period, I cannot believe. I do not, however, attach much importance to the point, since Paul testifies, that the apostleship of Peter pertained especially to the Jews, but his own specially to us. Therefore, in order that that compact which they made between themselves, nay, that the arrangement of the Holy Spirit may be firmly established among us, we ought to pay more regard to the apostleship of Paul than to that of Peter, since the Holy Spirit, in allotting them different provinces, destined Peter for the Jews and Paul for us. Let the Romanists, therefore, seek their primacy somewhere else than in the word of God, which gives not the least foundation for it.

Early witnesses testify otherwise. Dionysius, writing to the bishop of Rome around A.D. 70, states:

5. Thus publicly announcing himself as the first among God’s chief enemies, he was led on to the slaughter of the apostles. It is, therefore, recorded that Paul was beheaded in Rome itself, and that Peter likewise was crucified under Nero. This account of Peter and Paul is substantiated by the fact that their names are preserved in the cemeteries of that place even to the present day. . . .

8. And that they both suffered martyrdom at the same time is stated by Dionysius, bishop of Corinth, in his epistle to the Romans, in the following words:

You have thus by such an admonition bound together the planting of Peter and of Paul at Rome and Corinth. For both of them planted and likewise taught us in our Corinth. And they taught together in like manner in Italy, and suffered martyrdom at the same time.I have quoted these things in order that the truth of the history might be still more confirmed.(Eusebius, History of the Church, Book II, 25: 5,8)

F. F. Bruce, the renowned Protestant New Testament scholar, observed:

As for Peter’s association with the Roman church, this was not only a claim made from early days at Rome; it was conceded by churchmen from all over the Christian world. In the New Testament it is reflected in the greetings sent to the readers of 1 Peter from the church (literally, from “her”) “that is in Babylon, elect together with you” (1 Pet. 5:13) – if, as is most probable, Babylon is a code-word for Rome. (Peter, Stephen, James, and John, Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Pub. Co., 1979, p. 44)

The claim that Peter and Paul were joint-founders of the Roman church – attested, as we have seen, by Dionysius of Corinth – is earlier than the tracing of the succession of bishops of Rome back to them, which is first attested in Irenaeus but may go back to Hegesippus [Irenaeus, Against Heresies 3.3.1-3; for Hegesippus see Eusebius, Hist. Eccl. 4.22.3]. Strictly, Peter was no more founder of the Roman church than Paul was, but in Rome as elsewhere an apostle who was associated with a church in its early days was inevitably claimed as its founder. (Ibid., pp. 46-47)

The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (edited by F. L. Cross & E. A. Livingstone, Oxford University Press, second edition, 1983, “Peter,” p. 1068) asserts:

The tradition connecting St. Peter with Rome is early and unrivaled . . . Rom. 15.20-22 may point to the presence of another Apostle in Rome before St. Paul wrote, while the identification of ‘Babylon’ in 1 Pet. 5.13 . . . with Rome seems highly probable. St. Clement of Rome (1 Clem. 5) conjoins Peter and Paul as the outstanding heroes of the Faith and probably implies that Peter suffered martyrdom. St. Ignatius uses words (Rom. 4.2) which suggest that Peter and Paul were Apostles of special authority for the Roman church and St. Irenaeus (Adv. Haer., III. i. 2; III. iii. 1) states definitively that they founded that Church and instituted its episcopal succession. Others are Gaius of Rome and Dionysius of Corinth, both cited by Eusebius (H.E., II. xxv. 5-8).

Let us now come to the Primitive Church,

Yes, let’s . . .

that it may also appear that our opponents plume themselves on its support, not less falsely and unadvisedly than on the testimony of the word of God. When they lay it down as an axiom, that the unity of the Church cannot be maintained unless there be one supreme head on earth whom all the members should obey; and that, accordingly, our Lord gave the primacy to Peter, and thereafter, by right of succession, to the See of Rome, there to remain even to the end, they assert that this has always been observed from the beginning.

Indeed it has.

But since they improperly wrest many passages, I would first premise, that I deny not that the early Christians uniformly give high honour to the Roman Church, and speak of it with reverence.

Good.

This, I think, is owing chiefly to three causes. The opinion which had prevailed (I know not how), that that Church was founded and constituted by the ministry of Peter, had great effect in procuring influence and authority.

I have shown how, by documenting the fathers who asserted it.

Hence, in the East, it was, as a mark of honour, designated the Apostolic See. Secondly, as the seat of empire was there, and it was for this reason to be presumed, that the most distinguished for learning, prudence, skill, and experience, were there more than elsewhere, account was justly taken of the circumstance, lest the celebrity of the city, and the much more excellent gifts of God also, might seem to be despised.

In God’s providence, Christianity was to overcome the Roman Empire in due course. God went right to the center of secular power.

To these was added a third cause, that when the churches of the East, of Greece and of Africa, were kept in a constant turmoil by differences of opinion, the Church of Rome was calmer and less troubled. To this it was owing, that pious and holy bishops, when driven from their sees, often betook themselves to Rome as an asylum or haven. For as the people of the West are of a less acute and versatile turn of mind than those of Asia or Africa, so they are less desirous of innovations.

Which is a good thing, where orthodoxy is involved . . .

It therefore added very great authority to the Roman Church, that in those dubious times it was not so much unsettled as others, and adhered more firmly to the doctrine once delivered, as shall immediately be better explained.

Rome was always orthodox, and what was orthodox was eventually synonymous with Roman doctrine.

For these three causes, I say, she was held in no ordinary estimation, and received many distinguished testimonies from ancient writers.

A good start, especially for as big of a critic as Calvin . . .

But since on this our opponents would rear up a primacy and supreme authority over other churches, they, as I have said, greatly err.

Calvin raised his authority and that of his “church” over that of the universal Catholic Church, that had an unbroken 1500-year history. So on what self-consistent grounds (even before the issues involved are debated) could he even complain in this regard?

That this may better appear, I will first briefly show what the views of early writers are as to this unity which they so strongly urge. Jerome, in writing to Nepotian, after enumerating many examples of unity, descends at length to the ecclesiastical hierarchy. He says, “Every bishop of a church, every archpresbyter, every archdeacon, and the whole ecclesiastical order, depends on its own rulers.” Here a Roman presbyter speaks and commends unity in ecclesiastical order. Why does he not mention that all the churches are bound together by one Head as a common bond?

He did elsewhere, as I have documented in a past installment. It’s another case of Calvin demanding that everyone must mention everything all the time. This is unreasonable, and we have seen last time how even his claim of sola Scriptura would fall flat if we follow this excessive and unrealistic demand.

There was nothing more appropriate to the point in hand, and it cannot be said that he omitted it through forgetfulness; there was nothing he would more willingly have mentioned had the fact permitted.

The same fallacy . . . it’s a weak argument from silence.

He therefore undoubtedly owns, that the true method of unity is that which Cyprian admirably describes in these words: “The episcopate is one, part of which is held entire by each bishop, and the Church is one, which, by the increase of fecundity, extends more widely in numbers. As there are many rays of the sun and one light, many branches of a tree and one trunk, upheld by its tenacious root, and as very many streams flow from one fountain, and though numbers seem diffused by the largeness of the overflowing supply, yet unity is preserved entire in the source, so the Church, pervaded with the light of the Lord, sends her rays over the whole globe, and yet is one light, which is everywhere diffused without separating the unity of the body, extends her branches over the whole globe, and sends forth flowing streams; still the head is one, and the source one” (Cyprian, de Simplie. Prælat.). Afterwards he says, “The spouse of Christ cannot be an adulteress: she knows one house, and with chaste modesty keeps the sanctity of one bed.” See how he makes the bishopric of Christ alone universal, as comprehending under it the whole Church: See how he says that part of it is held entire by all who discharge the episcopal office under this head. Where is the primacy of the Roman See, if the entire bishopric resides in Christ alone, and a part of it is held entire by each?

I have documented St. Cyprian’s acceptance of the papacy already, too. But even if he had dissented against the authority of the papacy, as one father he is not infallible. There are many many fathers who do accept its authority (even in the east, which eventually split off and formed Orthodoxy), forming a consensus.

My object in these remarks is, to show the reader, in passing, that that axiom of the unity of an earthly kind in the hierarchy, which the Romanists assume as confessed and indubitable, was altogether unknown to the ancient Church.

This is false, as has been shown over and over in past installments (so that I have no necessity of repeating myself here), and will continue to be shown, by documentation of the fathers.

***

(originally 6-14-09)

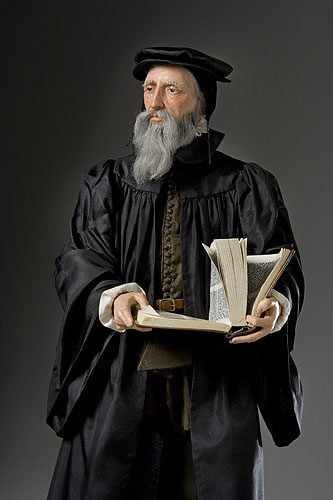

Photo credit: Historical mixed media figure of John Calvin produced by artist/historian George S. Stuart and photographed by Peter d’Aprix: from the George S. Stuart Gallery of Historical Figures archive [Wikimedia Commons / Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license]

***