This is an installment of a series of replies (see the Introduction and Master List) to much of Book IV (Of the Holy Catholic Church) of Institutes of the Christian Religion, by early Protestant leader John Calvin (1509-1564). I utilize the public domain translation of Henry Beveridge, dated 1845, from the 1559 edition in Latin; available online. Calvin’s words will be in blue. All biblical citations (in my portions) will be from RSV unless otherwise noted.

Related reading from yours truly:

Biblical Catholic Answers for John Calvin (2010 book: 388 pages)

A Biblical Critique of Calvinism (2012 book: 178 pages)

Biblical Catholic Salvation: “Faith Working Through Love” (2010 book: 187 pages; includes biblical critiques of all five points of “TULIP”)

*****

IV, 6:8-14

***

CHAPTER 6

*

*

But were I to concede to them what they ask with regard to Peter—viz. that he was the chief of the apostles, and surpassed the others in dignity—there is no ground for making a universal rule out of a special example, or wresting a single fact into a perpetual enactment, seeing that the two things are widely different.

That doesn’t follow. If there is something in the Bible that is clearly intended as a model, then it is indeed perpetual. Apostolic succession is observed in the Bible. That has to do with apostles and the bishops as their successors. This was the consensus of the fathers as well. Therefore, if Peter is shown to be the leader of the apostles, and preeminent, then it is perfectly plausible and to be expected that that office would continue, just as the office of bishop was to continue.

On the other hand it is silly to see some form of ecclesiology in the Bible and conclude that it was only for the first generation of Christians, or the first century (apostolic era) or some other arbitrary length of time. What sense does that make? Any sort of organization has a structure of authority.

One was chief among the apostles, just because they were few in number. If one man presided over twelve, will it follow that one ought to preside over a hundred thousand?

It does if said person is indicated in many ways in the Bible as having a sublime authority, and it follows in the sense of models and their successors later in history. It follows when Jesus built His Church on Peter himself (not just his faith). I could just as easily flip Calvin’s argument and say that if twelve need a leader, how much more would a hundred thousand need a leader? All human groups have need of that.

That twelve had one among them to direct all is nothing strange. Nature admits, the human mind requires, that in every meeting, though all are equal in power, there should be one as a kind of moderator to whom the others should look up. There is no senate without a consul, no bench of judges without a president or chancellor, no college without a provost, no company without a master. Thus there would be no absurdity were we to confess that the apostles had conferred such a primacy on Peter.

Exactly. But some human groups also have leaders who are heads in the sense that they have more power and authority than anyone else. The President of the United States is such a person. He has the power of veto and proclamation, and use of the “bully pulpit” (as Teddy Roosevelt called it) to influence millions of people more than others are able to, because of the prominence of his position.

But an arrangement which is effectual among a few must not be forthwith transferred to the whole world, which no one man is able to govern.

This isn’t logical. Why is it implausible to Calvin to have one worldwide leader? Obviously the one man can’t do everything (like Moses in the OT getting the advice from his father-in-law Jethro to divide his responsibilities lest he become exhausted). But he has the aid of bishops overseeing local areas. The Catholic Church follows that model. One man is still needed for unity’s sake. Nothing shows that more than the history and current state of Protestantism.

But (say they) it is observed that not less in nature as a whole, than in each of its parts, there is one supreme head. Proof of this it pleases them to derive from cranes and bees, which always place themselves under the guidance of one, not of several. I admit the examples which they produce; but do bees flock together from all parts of the world to choose one queen? Each queen is contented with her own hive.

Well, then the queen bee would be more analogous to a bishop.

So among cranes, each flock has its own king. What can they prove from this, except that each church ought to have its bishop?

The ultimate and conclusive prooftexts of the papacy come from the Bible, not analogies to cranes and bees.

They refer us to the examples of states, quoting from Homer, Οὐκ ἀγαθον πολυκοιρανιη, “a many-headed rule is not good;” and other “passages to the same effect from heathen writers in commendation of monarchy. The answer is easy. Monarchy is not lauded by Homer’s Ulysses, or by others, as if one individual ought to govern the whole world; but they mean to intimate that one kingdom does not admit of two kings, and that empire, as one expresses it (Lucan. Lib. 1), cannot bear a partner.

In the end, we must go by the Bible, but not it alone; the Bible as it has been interpreted by the fathers, and other eminent churchmen through the centuries.

Be it, however, as they will have it (though the thing is most absurd; be it),

It’s not absurd at all. It is the biblical model all down the line: popes, bishops, councils, priests, apostolic succession, authoritative Church and tradition (a magisterium), etc. Calvin’s ecclesiology is what is absurd, because it ditches every one of these elements that had always been held by the Catholic Church all along.

that it were good and useful for the whole world to be under one monarchy, I will not, therefore, admit that the same thing should take effect in the government of the Church. Her only Head is Christ, under whose government we are all united to each other, according to that order and form of policy which he himself has prescribed. Wherefore they offer an egregious insult to Christ, when under this pretext they would have one man to preside over the whole Church, seeing the Church can never be without a head, “even Christ, from whom the whole body fitly joined together, and compacted by that which every joint supplieth, according to the effectual working in the measure of every part, maketh increase of the body” (Eph. 4:15, 16).

This is what I call “super-pious rhetoric.” The problem is that it has no practical application at all. Of course, Christ is the Head. But Calvin knows, and everyone knows, that there is also human governance in the Church. The question then becomes not whether humans do this, but how they should do it; what is the structure?

See how all men, without exception, are placed in the body, while the honour and name of Head is left to Christ alone. See how to each member is assigned a certain measure, a finite and limited function, while both the perfection of grace and the supreme power of government reside only in Christ.

More of the same truisms that no one disputes in the slightest; but they do not rule out human Church offices.

I am not unaware of the cavilling objection which they are wont to urge—viz. that Christ is properly called the only Head, because he alone reigns by his own authority and in his own name; but that there is nothing in this to prevent what they call another ministerial head from being under him, and acting as his substitute. But this cavil cannot avail them, until they previously show that this office was ordained by Christ.

. . . which has been done in past installments. It’s been shown, for example, that Christ built His Church on Peter [with much Protestant scholarly support], not his confession. The latter position (Calvin’s) is now rejected by most reputable Protestant commentators, including Calvinists. Calvin was wrong. Thus, he didn’t see this clear indication of the papacy.

For the apostle teaches, that the whole subministration is diffused through the members, while the power flows from one celestial Head; or, if they will have it more plainly, since Scripture testifies that Christ is Head, and claims this honour for himself alone, it ought not to be transferred to any other than him whom Christ himself has made his vicegerent. But not only is there no passage to this effect, but it can be amply refuted by many passages.

Matthew 16:19 is exactly the passage Calvin is looking for. “Viceregent” is precisely one title that has been applied to the papacy by Protestant commentators, to show what “keys to the kingdom of heaven” meant. So Calvin has backed into the truth here, if only he could see it in the Bible.

Paul sometimes depicts a living image of the Church, but makes no mention of a single head. On the contrary, we may infer from his description, that it is foreign to the institution of Christ.

It appears that he does not explicitly discuss it, but he does implicitly, or by deduction and implication. For example, we see his response regarding the Jewish high priest:

Acts 23:4-5 Those who stood by said, “Would you revile God’s high priest?” [5] And Paul said, “I did not know, brethren, that he was the high priest; for it is written, `You shall not speak evil of a ruler of your people.'”

Thus, Paul retains the notion of a leader. Presumably, then, he would agree that there was also a Christian leader within the ranks of the Church. We also see how he acted in deference to Peter, in consulting with him alone when he began his apostolate, and how he singles Peter out by name, from the other apostles:

1 Corinthians 9:5 Do we not have the right to be accompanied by a wife, as the other apostles and the brothers of the Lord and Cephas?

1 Corinthians 15:5 and that he appeared to Cephas, then to the twelve.

Galatians 1:18 Then after three years I went up to Jerusalem to visit Cephas, and remained with him fifteen days.

Even Paul’s rebuke of Peter contains strong indications that he was the leader, because when there is a problem, it is good to nip it in the bud by going right to the top of the chain of command. Peter wasn’t the only one who acted insincerely and hypocritically:

Galatians 2:13 And with him the rest of the Jews acted insincerely, so that even Barnabas was carried away by their insincerity.

Yet when Paul rebuked the behavior, he went straight to Peter (Gal 2:11, 14). This proves that Peter was the leader. He was expected to set a better example. The rebuke itself doesn’t disprove that he was a leader; it only proves that he was a hypocrite in that instance, like we all are at times.

Christ, by his ascension, took away his visible presence from us, and yet he ascended that he might fill all things: now, therefore, he is present in the Church, and always will be. When Paul would show the mode in which he exhibits himself, he calls our attention to the ministerial offices which he employs: “Unto every one of us is given grace according to the measure of the gift of Christ;” “And he gave some, apostles; and some, prophets; and some, evangelists; and some, pastors and teachers.” Why does he not say, that one presided over all to act as his substitute?

Good question. I don’t know. But I know that the things I mentioned above are also relevant as to Paul’s opinion. And I know that many doctrines are in a relatively primitive state of development in the New Testament (even the Trinity itself: where its various aspects that were dogmatically adopted by the Church in the first seven centuries, are far more developed later on). I also know that the same sort of argument about not mentioning certain things and concluding that, therefore, they play no role, can be turned back on Calvin.

For example, in the very passage Calvin cites, talking about Church offices (Ephesians 4:11-15), another thing isn’t mentioned, either, that Calvin thinks does reign supreme, in terms of the rule of faith: Holy Scripture. I wrote in my book, A Biblical Defense of Catholicism (p. 16):

Note that in Ephesians 4:11-15 the Christian believer is “equipped,” “built up,” brought into “unity and mature manhood,” “knowledge” of Jesus, “the fullness of Christ,” and even preserved from doctrinal confusion by means of the teaching function of the Church. This is a far stronger statement of the “perfecting” of the saints than 2 Timothy 3:16-17, yet it doesn’t even mention Scripture.

In other words, if there is no pope as authority because he isn’t mentioned in this passage, there also is no Scripture as the only final infallible authority, because it isn’t mentioned here. The authority, as described in this passage, resides in the Church alone. Calvin’s argument proves too much. The fact remains that the Bible doesn’t always mention everything that could be mentioned, in every passage. Systematic theology must draw from the entire body of Holy Scripture. And this is what Catholics do when they see many biblical evidences for the papacy.

The passage particularly required this, and it ought not on any account to have been omitted if it had been true.

Then Scripture can’t be the ultimate authority, either, since it, too, isn’t mentioned in the same passage, which is rather wide-ranging. If Calvin doesn’t want that conclusion, that follows from his own internal logic, then he should also discard the argument about silence here disproving the existence of a papacy.

Christ, he says, is present with us. How? By the ministry of men whom he appointed over the government of the Church. Why not rather by a ministerial head whom he appointed his substitute? He speaks of unity, but it is in God and in the faith of Christ. He attributes nothing to men but a common ministry, and a special mode to each. Why, when thus commending unity, does he not, after saying, “one body, one Spirit, even as ye are called in one hope of your calling, one Lord, one faith, one baptism” (Eph. 4:4), immediately add, one Supreme Pontiff to keep the Church in unity?

Probably because he didn’t have to, since Matthew 16:19 was in everyone’s Bible, and it was crystal clear and understood by all. Peter was the rock. Paul calls Peter Cephas because that was the Aramaic word for “Rock.” Every time he uses that name, he is recalling the commission of Jesus in Matthew 16:19.

Nothing could have been said more aptly if the case had really been so. Let that passage be diligently pondered, and there will be no doubt that Paul there meant to give a complete representation of that sacred and ecclesiastical government to which posterity have given the name of hierarchy.

The fact that Scripture was not mentioned shows that Paul was not giving an absolutely complete picture of Christian authority.

Not only does he not place a monarchy among ministers, but even intimates that there is none. There can also be no doubt, that he meant to express the mode of connection by which believers unite with Christ the Head. There he not only makes no mention of a ministerial head, but attributes a particular operation to each of the members, according to the measure of grace distributed to each. Nor is there any ground for subtle philosophical comparisons between the celestial and the earthly hierarchy. For it is not safe to be wise above measure with regard to the former, and in constituting the latter, the only type which it behoves us to follow is that which our Lord himself has delineated in his own word.

And He gave primacy to Peter, in the many passages that have been examined previously.

I will now make them another concession, which they will never obtain from men of sound mind—viz. that the primacy of the Church was fixed in Peter, with the view of remaining for ever by perpetual succession. Still how will they prove that his See was so fixed at Rome, that whosoever becomes Bishop of that city is to preside over the whole world? By what authority do they annex this dignity to a particular place, when it was given without any mention of place?

By the fact that St. Peter and St. Paul were martyred there. By the fact of God’s Providence in going right to the heart of the Roman Empire and “Christianizing” it. For the world to be evangelized, Rome had to be converted first. That’s why the two great apostles ended their lives there.

Peter, they say, lived and died at Rome. What did Christ himself do? Did he not discharge his episcopate while he lived, and complete the office of the priesthood by dying at Jerusalem? The Prince of pastors, the chief Shepherd, the Head of the Church, could not procure honour for a place, and Peter, so far his inferior, could!

Jesus’ mission was to the Jews first (several scriptural indications). The apostles were to spread it to the Gentiles. That easily accounts for the difference.

Is not this worse than childish trifling?

Not at all. It makes perfect sense.

Christ conferred the honour of primacy on Peter. Peter had his See at Rome, therefore he fixed the seat of the primacy there. In this way the Israelites of old must have placed the seat of the primacy in the wilderness, where Moses, the chief teacher and prince of prophets, discharged his ministry and died.

No, because Moses was to take the Hebrews to the Promised Land. He didn’t get there, due to his disobedience, but that was the destination. Once there, the center of religious activity and administration was to be Jerusalem. That was the Old Covenant. Once the New Covenant and the gospel arrived, it was to spread to the Gentiles. Therefore, to best do that, the Church had to be centered in Gentile territories, and Rome: where the Empire was based, and where persecution was the greatest, was the obvious choice.

Let us see, however, how admirably they reason.

And let’s also see how fallaciously and “sub-biblically” Calvin often reasons . . .

Peter, they say, had the first place among the apostles; therefore, the church in which he sat ought to have the privilege. But where did he first sit? At Antioch, they say. Therefore, the church of Antioch justly claims the primacy. They acknowledge that she was once the first, but that Peter, by removing from it, transferred the honour which he had brought with him to Rome. For there is extant, under the name of Pope Marcellus, a letter to the presbyters of Antioch, in which he says, “The See of Peter, at the outset, was with you, and was afterwards, by the order of the Lord, translated hither.” Thus the church of Antioch, which was once the first, yielded to the See of Rome. But by what oracle did that good man learn that the Lord had so ordered? For if the question is to be determined in regular form, they must say whether they hold the privilege to be personal, or real, or mixed. One of the three it must be. If they say personal, then it has nothing to do with place; if real, then when once given to a place it is not lost by the death or departure of the person. It remains that they must hold it to be mixed; then the mere consideration of place is not sufficient unless the person also correspond. Let them choose which they will, I will forthwith infer, and easily prove, that Rome has no ground to arrogate the primacy.

I appeal back to previous statements. Whatever the particulars, God’s providence decreed that Peter and Paul were both martyred in Rome. That was not just a coincidence. In both Catholic and Calvinist theology, ultimately nothing really is. It all has a purpose. So it is surprising that Calvin sees no significance in this fact of the two most prominent Christian apostles, dying in the same place, in Europe; in the seat of the Roman Empire. True, it is not a “biblical ” argument; it is an argument from plausibility and common sense, regarding God’s plan in evangelizing Europe: which would be (institutionally speaking) the center of Christianity henceforth.

However, be it so. Let the primacy have been (as they vainly allege) transferred from Antioch to Rome. Why did not Antioch retain the second place? For if Rome has the first, simply because Peter had his See there at the end of his life, to which place should the second be given sooner than to that where he first had his See? How comes it, then, that Alexandria takes precedence of Antioch? How can the church of a disciple be superior to the See of Peter? If honour is due to a church according to the dignity of its founder, what shall we say of other churches? Paul names three individuals who seemed to be pillars—viz. James, Peter, and John (Gal. 2:9). If, in honour of Peter, the first place is given to the Roman See, do not the churches of Ephesus and Jerusalem, where John and James were fixed, deserve the second and third places? But in ancient times Jerusalem held the last place among the Patriarchates, and Ephesus was not able to secure even the lowest corner. Other churches too have passed away, churches which Paul founded, and over which the apostles presided. The See of Mark, who was only one of the disciples, has obtained honour. Let them either confess that that arrangement was preposterous, or let them concede that it is not always true that each church is entitled to the degree of honour which its founder possessed.

Non-Roman Sees are essentially equal. The Holy See in Rome was preeminent. It is irrelevant to wrangle over these other Sees, to see which should have more prominence. That is a problem for the Orthodox, not Catholics.

But I do not see that any credit is due to their allegation of Peter’s occupation of the Roman See. Certainly it is, that the statement of Eusebius, that he presided over it for twenty-five years, is easily refuted. For it appears from the first and second chapters of Galatians, that he was at Jerusalem about twenty years after the death of Christ, and afterwards came to Antioch. How long he remained here is uncertain; Gregory counts seven, and Eusebius twenty-five years. But from our Saviour’s death to the end of Nero’s reign (under which they state that he was put to death), will be found only thirty-seven years. For our Lord suffered in the eighteenth year of the reign of Tiberius. If you cut off the twenty years, during which, as Paul testifies, Peter dwelt at Jerusalem, there will remain at most seventeen years; and these must be divided between his two episcopates. If he dwelt long at Antioch, his See at Rome must have been of short duration. This we may demonstrate still more clearly. Paul wrote to the Romans while he was on his journey to Jerusalem, where he was apprehended and conveyed to Rome (Rom. 15:15, 16). It is therefore probable that this letter was written four years before his arrival at Rome. Still there is no mention of Peter, as there certainly would have been if he had been ruling that church. Nay, in the end of the Epistle, where he enumerates a long list of individuals whom he orders to be saluted, and in which it may be supposed he includes all who were known to him, he says nothing at all of Peter. To men of sound judgment, there is no need here of a long and subtle demonstration; the nature of the case itself, and the whole subject of the Epistle, proclaim that he ought not to have passed over Peter if he had been at Rome.

There is biblical proof for Peter being in Rome (Calvin seems to equivocate and is a bit unclear what he actually thinks regarding this matter). The Catholic Answers tract, Was Peter in Rome? states:

“The Church here in Babylon, united with you by God’s election, sends you her greeting, and so does my son, Mark” (1 Pet. 5:13, Knox). Babylon is a code-word for Rome. It is used that way multiple times in works like the Sibylline Oracles (5:159f), the Apocalypse of Baruch (2:1), and 4 Esdras (3:1). Eusebius Pamphilius, in The Chronicle, composed about A.D. 303, noted that “It is said that Peter’s first epistle, in which he makes mention of Mark, was composed at Rome itself; and that he himself indicates this, referring to the city figuratively as Babylon.”

Consider now the other New Testament citations: “Another angel, a second, followed, saying, ‘Fallen, fallen is Babylon the great, she who made all nations drink the wine of her impure passion’” (Rev. 14:8). “The great city was split into three parts, and the cities of the nations fell, and God remembered great Babylon, to make her drain the cup of the fury of his wrath” (Rev. 16:19). “[A]nd on her forehead was written a name of mystery: ‘Babylon the great, mother of harlots and of earth’s abominations’” (Rev. 17:5). “And he called out with a mighty voice, ‘Fallen, fallen is Babylon the great’” (Rev. 18:2). “[T]hey will stand far off, in fear of her torment, and say, ‘Alas! alas! thou great city, thou mighty city, Babylon! In one hour has thy judgment come’” (Rev. 18:10). “So shall Babylon the great city be thrown down with violence” (Rev. 18:21).

These references can’t be to the one-time capital of the Babylonian empire. That Babylon had been reduced to an inconsequential village by the march of years, military defeat, and political subjugation; it was no longer a “great city.” It played no important part in the recent history of the ancient world. From the New Testament perspective, the only candidates for the “great city” mentioned in Revelation are Rome and Jerusalem.

. . . The authorities knew that Peter was a leader of the Church, and the Church, under Roman law, was considered organized atheism. (The worship of any gods other than the Roman was considered atheism.) Peter would do himself, not to mention those with him, no service by advertising his presence in the capital—after all, mail service from Rome was then even worse than it is today, and letters were routinely read by Roman officials. Peter was a wanted man, as were all Christian leaders. Why encourage a manhunt? We also know that the apostles sometimes referred to cities under symbolic names (cf. Rev. 11:8).

Even the thoroughly Protestant Bible Knowledge Commentary (p. 857) thinks the “Babylon = Rome” explanation for 1 Peter 5:13 quite plausible. Bible scholar Reinhard Feldmeier takes the same position (The First Letter of Peter, Baylor University Press, 2008, pp. 41-42). A. T. Robertson, in Word Pictures in the New Testament (introduction for 1st Peter) agrees:

So we can think of Rome as the place of writing and that Peter uses “Babylon” to hide his actual location from Nero.

Many other Protestant commentators could be brought forth in favor of this opinion. It’s not just a Catholic argument. It is a legitimate exegetical opinion, regardless of affiliation. See also:

Peter’s Roman Residency (Catholic Answers)

Was St. Peter Ever in Rome? Refuting a Persistent Protestant Prejudice (Phil Porvaznik)

***

(originally 6-13-09)

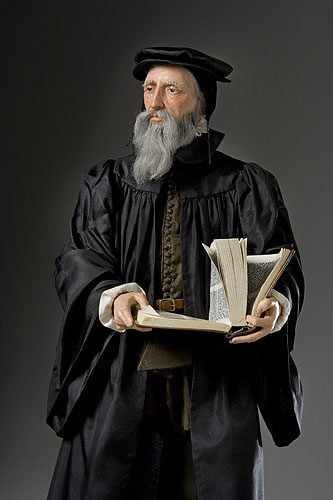

Photo credit: Historical mixed media figure of John Calvin produced by artist/historian George S. Stuart and photographed by Peter d’Aprix: from the George S. Stuart Gallery of Historical Figures archive [Wikimedia Commons / Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license]

***