This is an installment of a series of replies (see the Introduction and Master List) to much of Book IV (Of the Holy Catholic Church) of Institutes of the Christian Religion, by early Protestant leader John Calvin (1509-1564). I utilize the public domain translation of Henry Beveridge, dated 1845, from the 1559 edition in Latin; available online. Calvin’s words will be in blue. All biblical citations (in my portions) will be from RSV unless otherwise noted.

Related reading from yours truly:

Biblical Catholic Answers for John Calvin (2010 book: 388 pages)

A Biblical Critique of Calvinism (2012 book: 178 pages)

Biblical Catholic Salvation: “Faith Working Through Love” (2010 book: 187 pages; includes biblical critiques of all five points of “TULIP”)

*****

IV, 13:1-6

***

CHAPTER 13

*

It is indeed deplorable that the Church, whose freedom was purchased by the inestimable price of Christ’s blood, should have been thus oppressed by a cruel tyranny, and almost buried under a huge mass of traditions;

There are, of course (biblically speaking) good and bad traditions, but Calvin rarely makes that crucial distinction. Nor does he ever admit that Protestant innovations and novelties and corruptions are examples of bad tradition.

but, at the same time, the private infatuation of each individual shows, that not without just cause has so much power been given from above to Satan and his ministers. It was not enough to neglect the command of Christ, and bear any burdens which false teachers might please to impose, but each individual behoved to have his own peculiar burdens, and thus sink deeper by digging his own cavern. This has been the result when men set about devising vows, by which a stronger and closer obligation might be added to common ties. Having already shown that the worship of God was vitiated by the audacity of those who, under the name of pastors, domineered in the Church, when they ensnared miserable souls by their iniquitous laws, it will not be out of place here to advert to a kindred evil, to make it appear that the world, in accordance with its depraved disposition, has always thrown every possible obstacle in the way of the helps by which it ought to have been brought to God.

The usual anti-Catholic prattle . . .

Moreover, that the very grievous mischief introduced by such vows may be more apparent, let the reader attend to the principles formerly laid down. First, we showed (Book 2 chap. 8 sec. 5) that everything requisite for the ordering of a pious and holy life is comprehended in the law. Secondly, we showed that the Lord, the better to dissuade us from devising new works, included the whole of righteousness in simple obedience to his will. If these positions are true, it is easy to see that all fictitious worship, which we ourselves devise for the purpose of serving God, is not in the least degree acceptable to him, how pleasing soever it may be to us. And, unquestionably, in many passages the Lord not only openly rejects, but grievously abhors such worship.

Calvin’s opposition to traditional Christian, Catholic worship is irrational, bigoted, and wrongheaded. If he actually presents some arguments for his antipathy, then I’ll be happy to deal with them one-by-one.

Hence arises a doubt with regard to vows which are made without any express authority from the word of God; in what light are they to be viewed? can they be duly made by Christian men, and to what extent are they binding? What is called a promise among men is a vow when made to God. Now, we promise to men either things which we think will be acceptable to them, or things which we in duty owe them. Much more careful, therefore, ought we to be in vows which are directed to God, with whom we ought to act with the greatest seriousness. Here superstition has in all ages strangely prevailed; men at once, without judgment and without choice, vowing to God whatever came into their minds, or even rose to their lips. Hence the foolish vows, nay, monstrous absurdities, by which the heathen insolently sported with their gods. Would that Christians had not imitated them in this their audacity! Nothing, indeed, could be less becoming; but it is obvious that for some ages nothing has been more usual than this misconduct—the whole body of the people everywhere despising the Law of God, and burning with an insane zeal of vowing according to any dreaming notion which they had formed. I have no wish to exaggerate invidiously, or particularise the many grievous sins which have here been committed; but it seemed right to advert to it in passing, that it may the better appear, that when we treat of vows we are not by any means discussing a superfluous question.

Having ridiculously exaggerated the abuses of vows, Calvin claims he has no wish to do so. How charming. As usual, Calvin will paint things in the darkest colors imaginable, with sweeping terms and dramatic flourishes, leading to a conclusion that the thing in question (here, vows), presented as a gross caricature of actual reality, should be essentially eliminated.

He does this over and over, leading one to rightly conclude that he is no reformer, but rather, a revolutionary. Vows have a strong biblical basis. They simply need to be correctly understood and applied in the lives of people: not scorned and ditched altogether.

Vows and oaths have a perfectly biblical basis. Here are three Protestant sources that verify this:

It is no sin to vow or not to vow, but if made . . . a vow is as sacredly binding as an oath (Deut 23:21-23) . . . The seriousness of oaths is emphasized in the laws of Moses (Ex 20:7, Lev 19:12) . . . Ezekiel speaks as if perjury were punishable by death (Ezek 17:16 ff.) . . . Christ taught that oaths were binding (Matt 5:33) . . . Christ himself accepted the imprecatory oath (Matt 26:63 ff.), and Paul also swore by an oath (2 Cor 1:23, Gal 1:20) . . . God bound himself by an oath (Heb. 6:13-18). (J. D. Douglas, editor, The New Bible Dictionary, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans, 1962, 1313, 902)

*Oaths were solemn commitments and not to be taken lightly. The 3rd commandment of the Decalog forbids oaths that are made thoughtlessly (Ex 20:7, Deut 5:11); the 9th commandment forbids perjury. An oath must be fulfilled . . . (Ecc 5:4-5). (Allen C. Myers, editor, Eerdmans Bible Dictionary, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans, 1987 [English revision of Bijbelse Encyclopedie, edited by W. H. Gispen, Kampen, Netherlands: J. H. Kok, revised edition, 1975], translated by Raymond C. Togtman & Ralph W. Vunderink, 773-774)

The apostle Paul . . . had his hair cut off . . . ‘for he had taken a vow’ (Acts 18:18) . . . Vowing was voluntary. But after a vow was made, it had to be performed . . . Deception in vowing is an affront to God and brings His curse (Mal 1:14) . . . Lying about an oath could result in death (Ezek 17:16-18). Jesus Himself was bound by an oath (Matt 26:63-4), as was Paul (2 Cor l:23, Gal 1:20). Even God bound Himself by an oath. (Herbert, Lockyer, Sr., editor, Nelson’s Illustrated Bible Dictionary, Nashville: Nelson, 1986, 1088, 767)

If we would avoid error in deciding what vows are legitimate, and what preposterous, three things must be attended to—viz. who he is to whom the vow is made; who we are that make it; and, lastly, with what intention we make it. In regard in the first, we should consider that we have to do with God, whom our obedience so delights, that he abominates all will-worship, how specious and splendid soever it be in the eyes of men (Col. 2:23). If all will-worship, which we devise without authority, is abomination to God, it follows that no worship can be acceptable to him save that which is approved by his word. Therefore, we must not arrogate such licence to ourselves as to presume to vow anything to God without evidence of the estimation in which he holds it. For the doctrine of Paul, that whatsoever is not of faith is sin (Rom. 14:23), while it extends to all actions of every kind, certainly applies with peculiar force in the case where the thought is immediately turned towards God. Nay, if in the minutest matters (Paul was then speaking of the distinction of meats) we err or fall, where the sure light of faith shines not before us, how much more modesty ought we to use when we attempt a matter of the greatest weight? For in nothing ought we to be more serious than in the duties of religion. In vows, then, our first precaution must be, never to proceed to make any vow without having previously determined in our conscience to attempt nothing rashly. And we shall be safe from the danger of rashness when we have God going before, and, as it were, dictating from his word what is good, and what is useless.

No argument with the general principles: only regarding how Calvin specifically applies them. Also, when he says “approved by his word,” this is accompanied by the usual wrongheaded assumptions involved in sola Scriptura (often requiring explicit biblical indication where that is not necessary).

In the second point which we have mentioned as requiring consideration is implied, that we measure our strength, that we attend to our vocation so as not to neglect the blessing of liberty which God has conferred upon us. For he who vows what is not within his means, or is at variance with his calling, is rash, while he who contemns the beneficence of God in making him lord of all things, is ungrateful.

*

When I speak thus, I mean not that anything is so placed in our hand, that, leaning on our own strength, we may promise it to God. For in the Council of Arausica (cap. 11) it was most truly decreed, that nothing is duly vowed to God save what we have received from his hand, since all things which are offered to him are merely his gifts.

Catholics fully agree with this.

But seeing that some things are given to us by the goodness of God, and others withheld by his justice, every man should have respect to the measure of grace bestowed on him, as Paul enjoins (Rom. 12:3; 1 Cor. 12:11). All then I mean here is, that your vows should be adapted to the measure which God by his gifts prescribes to you, lest by attempting more than he permits, you arrogate too much to yourself, and fall headlong.

Exactly.

For example, when the assassins, of whom mention is made in the Acts, vowed “that they would neither eat nor drink till they had killed Paul” (Acts 23:12), though it had not been an impious conspiracy, it would still have been intolerably presumptuous, as subjecting the life and death of a man to their own power. Thus Jephthah suffered for his folly, when with precipitate fervour he made a rash vow (Judges 11:30).

Vows rashly made are foolish and a bad thing; of course.

Of this class, the first place of insane audacity belongs to celibacy.

And now we start to go off into irrationality and prejudice . . . .

Priests, monks, and nuns, forgetful of their infirmity,

What infirmity? Being called to the religious life? May many more folks be afflicted with this “infirmity”!

are confident of their fitness for celibacy.

If God calls them to such a life; sure. Let every one live in the calling that God has granted them.

But by what oracle have they been instructed, that the chastity which they vow to the end of life, they will be able through life to maintain?

God: the one Who calls.

They hear the voice of God concerning the universal condition of mankind, “It is not good that the man should be alone” (Gen. 2:18).

Obviously, it is not “universal,” or else Jesus wouldn’t have noted its non-universality (Matthew 19); nor would Paul have done so (1 Corinthians 7), nor would Jesus, His disciples, John the Baptist, and many other holy men and women, have been celibate.

They understand, and I wish they did not feel that the sin remaining in us is armed with the sharpest stings. How can they presume to shake off the common feelings of their nature for a whole lifetime, seeing the gift of continence is often granted for a certain time as occasion requires?

Because God called them to it; therefore He continues to enable them to fulfill the vow:

Philippians 2:13 for God is at work in you, both to will and to work for his good pleasure.

Philippians 4:13 I can do all things in him who strengthens me.

Calvin either lacks faith that God is able to do these things in human beings, or he is oddly unfamiliar with biblical passages such as the above.

In such perverse conduct they must not expect God to be their helper; let them rather remember the words, “Ye shall not tempt the Lord your God” (Deut. 6:16). But it is to tempt the Lord to strive against the nature implanted by him, and to spurn his present gifts as if they did not appertain to us.

How can something be “perverse” and an example of tempting God, that was expressly recommended and extolled by our Lord Jesus and the apostle Paul? This is curious logic.

This they not only do, but marriage, which God did not think it unbecoming his majesty to institute, which he pronounced honourable in all, which Christ our Lord sanctified by his presence, and which he deigned to honour with his first miracle, they presume to stigmatise as pollution,

This is fallacious “either/or” reasoning. Catholicism is caricatured (because Calvin can’t comprehend celibacy), as devaluing marriage simply because it recognizes also a category of celibacy and being “married to the Lord.” The problem obviously resides with Calvin’s unbiblical logic and with people who take this vow, that have no business doing so. Neither “problem” casts into doubt the veracity of the principle and the calling, itself.

so extravagant are the terms in which they eulogise every kind of celibacy; as if in their own life they did not furnish a clear proof that celibacy is one thing and chastity another. This life, however, they most impudently style angelical, thereby offering no slight insult to the angels of God, to whom they compare whoremongers and adulterers, and something much worse and fouler still. And, indeed, there is here very little occasion for argument, since they are abundantly refuted by fact. For we plainly see the fearful punishments with which the Lord avenges this arrogance and contempt of his gifts from overweening confidence. More hidden crimes I spare through shame; what is known of them is too much.

Some people abuse a good thing. Why should this some shocking thing? Whatever is abused (which is virtually everything) does not thereby become evil. The Bible itself, for example, is abused all the time, but it doesn’t change the fact that it is very good, and God’s inspired revelation.

Beyond all controversy, we ought not to vow anything which will hinder us in fulfilling our vocation; as if the father of a family were to vow to leave his wife and children, and undertake other burdens; or one who is fit for a public office should, when elected to it, vow to live private. But the meaning of what we have said as to not despising our liberty may occasion some difficulty if not explained. Wherefore, understand it briefly thus: Since God has given us dominion over all things, and so subjected them to us that we may use them for our convenience, we cannot hope that our service will be acceptable to God if we bring ourselves into bondage to external things, which ought to be subservient to us. I say this, because some aspire to the praise of humility, for entangling themselves in a variety of observances from which God for good reason wished us to be entirely free. Hence, if we would escape this danger, let us always remember that we are by no means to withdraw from the economy which God has appointed in the Christian Church.

Good principles, but applied wrongly or fallaciously, as explained.

I come now to my third position—viz that if you would approve your vow to God, the mind in which you undertake it is of great moment. For seeing that God looks not to the outward appearance but to the heart, the consequence is, that according to the purpose which the mind has in view, the same thing may at one time please and be acceptable to him, and at another be most displeasing. If you vow abstinence from wine, as if there were any holiness in so doing, you are superstitious; but if you have some end in view which is not perverse, no one can disapprove.

Good. God looks at the heart.

Now, as far as I can see, there are four ends to which our vows may be properly directed; two of these, for the sake of order, I refer to the past, and two to the future. To the past belong vows by which we either testify our gratitude toward God for favours received, or in order to deprecate his wrath, inflict punishment on ourselves for faults committed. The former, let us if you please call acts of thanksgiving; the latter, acts of repentance. Of the former class, we have an example in the tithes which Jacob vowed (Gen. 28:20), if the Lord would conduct him safely home from exile; and also in the ancient peace-offerings which pious kings and commanders, when about to engage in a just war, vowed that they would give if they were victorious, or, at least, if the Lord would deliver them when pressed by some greater difficulty. Thus are to be understood all the passages in the Psalms which speak of vows (Ps. 22:26; 56:13; 116:14, 18). Similar vows may also be used by us in the present day, whenever the Lord has rescued us from some disaster or dangerous disease, or other peril. For it is not abhorrent from the office of a pious man thus to consecrate a votive offering to God as a formal symbol of acknowledgment that he may not seem ungrateful for his kindness. The nature of the second class it will be sufficient to illustrate merely by one familiar example. Should any one, from gluttonous indulgence, have fallen into some iniquity, there is nothing to prevent him, with the view of chastising his intemperance, from renouncing all luxuries for a certain time, and in doing so, from employing a vow for the purpose of binding himself more firmly. And yet I do not lay down this as an invariable law to all who have similarly offended; I merely show what may be lawfully done by those who think that such a vow will be useful to them. Thus while I hold it lawful so to vow, I at the same time leave it free.

No particular disagreement.

*

The vows which have reference to the future

How can a vow not pertain to the future? How can one vow about a past event?

tend partly, as we have said, to render us more cautious, and partly to act as a kind of stimulus to the discharge of duty. A man sees that he is so prone to a certain vice, that in a thing which is otherwise not bad he cannot restrain himself from forthwith falling into evil: he will not act absurdly in cutting off the use of that thing for some time by a vow. If, for instance, one should perceive that this or that bodily ornament brings him into peril, and yet allured by cupidity he eagerly longs for it, what can he do better than by throwing a curb upon himself, that is, imposing the necessity of abstinence, free himself from all doubt? In like manner, should one be oblivious or sluggish in the necessary duties of piety, why should he not, by forming a vow, both awaken his memory and shake off his sloth? In both, I confess, there is a kind of tutelage, but inasmuch as they are helps to infirmity, they are used not without advantage by the ignorant and imperfect. Hence we hold that vows which have respect to one of these ends, especially in external things, are lawful, provided they are supported by the approbation of God, are suitable to our calling, and are limited to the measure of grace bestowed upon us.

No disagreement.

It is not now difficult to infer what view on the whole ought to be taken of vows. There is one vow common to all believers, which taken in baptism we confirm, and as it were sanction, by our Catechism, and partaking of the Lord’s Supper. For the sacraments are a kind of mutual contracts by which the Lord conveys his mercy to us, and by it eternal life, while we in our turn promise him obedience. The formula, or at least substance, of the vow is, That renouncing Satan we bind ourselves to the service of God, to obey his holy commands, and no longer follow the depraved desires of our flesh. It cannot be doubted that this vow, which is sanctioned by Scripture, nay, is exacted from all the children of God, is holy and salutary. There is nothing against this in the fact, that no man in this life yields that perfect obedience to the law which God requires of us. This stipulation being included in the covenant of grace, comprehending forgiveness of sins and the spirit of holiness, the promise which we there make is combined both with entreaty for pardon and petition for assistance. It is necessary, in judging of particular vows, to keep the three former rules in remembrance: from them any one will easily estimate the character of each single vow.

Excellent.

Do not suppose, however, that I so commend the vows which I maintain to be holy that I would have them made every day. For though I dare not give any precept as to time or number, yet if any one will take my advice, he will not undertake any but what are sober and temporary.

What becomes of marriage vows, then?

If you are ever and anon launching out into numerous vows, the whole solemnity will be lost by the frequency, and you will readily fall into superstition.

Yes; vows are too serious to be made constantly. That would cheapen their gravity.

If you bind yourself by a perpetual vow, you will have great trouble and annoyance in getting free, or, worn out by length of time, you will at length make bold to break it.

So much for marriage and lifelong commitment to the priesthood, to the religious life, or to the Protestant sense of pastoral ordination.

(originally 9-21-09)

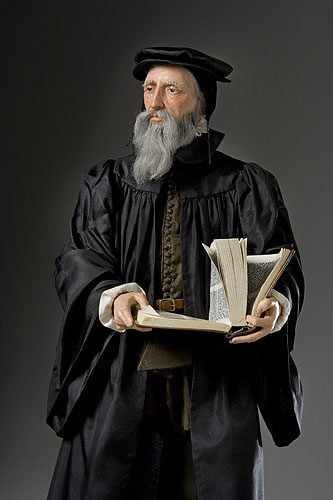

Photo credit: Historical mixed media figure of John Calvin produced by artist/historian George S. Stuart and photographed by Peter d’Aprix: from the George S. Stuart Gallery of Historical Figures archive [Wikimedia Commons / Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license]

***