This is an installment of a series of replies (see the Introduction and Master List) to much of Book IV (Of the Holy Catholic Church) of Institutes of the Christian Religion, by early Protestant leader John Calvin (1509-1564). I utilize the public domain translation of Henry Beveridge, dated 1845, from the 1559 edition in Latin; available online. Calvin’s words will be in blue. All biblical citations (in my portions) will be from RSV unless otherwise noted.

Related reading from yours truly:

Biblical Catholic Answers for John Calvin (2010 book: 388 pages)

A Biblical Critique of Calvinism (2012 book: 178 pages)

Biblical Catholic Salvation: “Faith Working Through Love” (2010 book: 187 pages; includes biblical critiques of all five points of “TULIP”)

*****

IV, 13:11-21

***

CHAPTER 13

If they deny this, I should like to know why they honour their own order only with the title of perfection, and deny it to all other divine callings. I am not unaware of the sophistical solution that their order is not so called because it contains perfection in itself, but because it is the best of all for acquiring perfection. When they would extol themselves to the people; when they would lay a snare for rash and ignorant youth; when they would assert their privileges and exalt their own dignity to the disparagement of others, they boast that they are in a state of perfection. When they are too closely pressed to be able to defend this vain arrogance, they betake themselves to the subterfuge that they have not yet obtained perfection, but that they are in a state in which they aspire to it more than others; meanwhile, the people continue to admire as if the monastic life alone were angelic, perfect, and purified from every vice.

Calvin here is attacking what is known as the “evangelical counsels.” The Catholic Encyclopedia article by the same name, provides the answer to his extreme and misguided criticisms:

Christ in the Gospels laid down certain rules of life and conduct which must be practiced by every one of His followers as the necessary condition for attaining to everlasting life. These precepts of the Gospel practically consist of the Decalogue, or Ten Commandments, of the Old Law, interpreted in the sense of the New. Besides these precepts which must be observed by all under pain of eternal damnation, He also taught certain principles which He expressly stated were not to be considered as binding upon all, or as necessary conditions without which heaven could not be attained, but rather as counsels for those who desired to do more than the minimum and to aim at Christian perfection, so far as that can be obtained here upon earth. Thus (Matthew 19:16 sq.) when the young man asked Him what he should do to obtain eternal life, Christ bade him to “keep the commandments”. That was all that was necessary in the strict sense of the word, and by thus keeping the commands which God had given eternal life could be obtained. But when the young man pressed further, Christ told him: “If thou wilt be perfect, go sell what thou hast, and give to the poor”. So again, in the same chapter, He speaks of “eunuchs who have made themselves eunuchs for the kingdom of heaven”, and added, “He that can receive it, let him receive it”.

This distinction between the precepts of the Gospel, which are binding on all, and the counsels, which are the subject of the vocation of the comparatively few, has ever been maintained by the Catholic Church. It has been denied by heretics in all ages, and especially by many Protestants in the sixteenth and following centuries, on the ground that, inasmuch as all Christians are at all times bound, if they would keep God’s Commandments, to do their utmost, and even so will fall short of perfect obedience, no distinction between precepts and counsels can rightly be made. The opponents of the Catholic doctrine base their opposition on such texts as Luke 17:10, “When ye have done all that is commanded you, say, we are unprofitable servants”. It is impossible, they say, to keep the Commandments adequately. To teach further “counsels” involves either the absurdity of advising what is far beyond all human capacity, or else the impiety of minimizing the commands of Almighty God. The Catholic doctrine, however, founded, as we have seen, upon the words of Christ in the Gospel, is also supported by St. Paul. In 1 Corinthians 7, for instance, he not only presses home the duty incumbent on all Christians of keeping free from all sins of the flesh, and of fulfilling the obligations of the married state, if they have taken those obligations upon themselves, but also gives his “counsel” in favour of the unmarried state and of perfect chastity, on the ground that it is thus more possible to serve God with an undivided allegiance. Indeed, the danger in the Early Church, and even in Apostolic times, was not that the “counsels” would be neglected or denied, but that they should be exalted into commands of universal obligation, “forbidding to marry” (1 Timothy 4:3), and imposing poverty as a duty on all. . . .

To sum up: it is possible to be rich, and married, and held in honour by all men, and yet keep the Commandments and to enter heaven. Christ’s advice is, if we would make sure of everlasting life and desire to conform ourselves perfectly to the Divine will, that we should sell our possessions and give the proceeds to others who are in need, that we should live a life of chastity for the Gospel’s sake, and, finally, should not seek honours or commands, but place ourselves under obedience. These are the Evangelical Counsels, and the things which are counselled are not set forward so much as good in themselves, as in the light of means to an end and as the surest and quickest way of obtaining everlasting life.

Under this pretence they ply a most gainful traffic, while their moderation lies buried in a few volumes. Who sees not that this is intolerable trifling? But let us treat with them as if they ascribed nothing more to their profession than to call it a state for acquiring perfection. Surely by giving it this name, they distinguish it by a special mark from other modes of life. And who will allow such honour to be transferred to an institution of which not one syllable is said in approbation, while all the other callings of God are deemed unworthy of the same, though not only commanded by his sacred lips, but adorned with distinguished titles?

Here is the patented Calvin method of exaggerating and then concluding with the absurd, extreme contrast: one thing pitted against another. That is not Catholic thinking. It is Calvin’s gross distortion of Catholic thinking, passed off as if it were the real thing. This is what is known in logic as a “straw man.” Calvin is quite adept at constructing them. Arguably, then, he should have taken up farming rather than theology.

And how great the insult offered to God, when some device of man is preferred to all the modes of life which he has ordered, and by his testimony approved?

Isn’t this a marvelous rhetorical contrast? The Catholics are dumb and wicked, while Calvin and his cohorts are most honorable, noble, and righteous. What fool would deny that Calvin is superior to the lowly “papists” — awash in their arbitrary traditions of men; hypocrites one and all?

But let them say I calumniated them when I declared that they were not contented with the rule prescribed by God. Still, though I were silent, they more than sufficiently accuse themselves; for they plainly declare that they undertake a greater burden than Christ has imposed on his followers, since they promise that they will keep evangelical counsels regarding the love of enemies, the suppression of vindictive feelings, and abstinence from swearing, counsels to which Christians are not commonly astricted.

Exactly.

In this what antiquity can they pretend?

1 Corinthians 7, Matthew 19. Both are quite ancient — first century! — and of impeccable authority: Jesus and Paul.

None of the ancients ever thought of such a thing: all with one voice proclaim that not one syllable proceeded from Christ which it is not necessary to obey.

Renouncing wealth and possessions, or deciding to be celibate, and other similar sacrifices are not matters of command for all, but of special heroic sacrifice for those called to it. Thus, Calvin’s remark is a complete non sequitur. It’s illogical; it has nothing to do with the essential aspects of the question at hand. He makes his characteristically sweeping claim: “none of the ancients . . . “ The historical record, alas, shows otherwise:

St. Ignatius of Antioch

Ye virgins, be subject to Christ in purity, not counting marriage an abomination, but desiring that which is better, not for the reproach of wedlock, but for the sake of meditating on the law. (Epistle to the Philadelphians [Syriac version], Ch IV)

Athenagoras

You would find many among us, both men and women, growing old unmarried, in hope of living in closer communion with God. (A Plea for the Christians, Chap. XXXIII)

St. Clement of Alexandria

Such a person [who cannot exercise self-control] is not sinning against the covenant [by marrying], but neither is he fulfilling the highest purpose of the gospel ethic. (Stromata 3.82.4; on 1 Cor 7:9; from Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture, general editor: Thomas C. Oden, Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press, Vol. VII: 1-2 Corinthians, 1999, p. 62)

Origen

Some rules are given as commandments of God, while others are more flexible and left by God top the decision of the individual. The first kind are those commandments which pertain to salvation. The others are better, because even if we do not keep them, we shall still be saved. There is no merit in doing what is obligatory, but there is in doing that which is optional. (Commentary on 1 Corinthians 3.39.2-6; on 1 Cor 7:25; in Oden, ibid., p. 69)

St. Ambrose

Marriage is good because through it the means of human continuity are found. But virginity is better, because through it are attained the inheritance of a heavenly kingdom and a continuity of heavenly rewards. (Synodal Letters 44; in Oden, ibid., p. 72)

St. Jerome

It is in our power, whether we want to be perfect. But whoever wants to be perfect, should sell all that he has…and when he has sold, give everything to the poor. (Commentarium in Evangelium Matthaei, P.L. XXVI, p. 148)

St. John Chrysostom

Having spoken then of the eunuchs that are eunuchs for naught and fruitlessly, unless with the mind they too practice temperance, and of those that are virgins for Heaven’s sake, He proceeds again to say, “He that is able to receive it, let him receive it,” at once making them more earnest by showing that the good work is exceeding in greatness, and not suffering the thing to be shut up in the compulsion of a law, because of His unspeakable gentleness. And this He said, when He showed it to be most possible, in order that the emulation of the free choice might be greater.And if it is of free choice, one may say, how does He say, at the beginning, “All men do not receive it, but they to whom it is given?” That you might learn that the conflict is great, not that you should suspect any compulsory allotments. For it is given to those who will it. But He spoke thus to show that much influence from above is needed by him who enters these lists, of which influence He who is willing shall surely partake. (Homily 62 on Matthew, PG 58:600)

Paul states that continence is better, but he does not attempt to pressure those who cannot attain to it. (Homilies on the Epistles of Paul to the Corinthians 19.3; on 1 Cor 7:8; from Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture, general editor: Thomas C. Oden, Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press, Vol. VII: 1-2 Corinthians, 1999, p. 62)

Paul makes his case for celibacy, but in the end he leaves it up to the free choice of the individual. If after all this he were to resort to compulsion, it would look as if he did not really believe his own statements. (Homilies on the Epistles of Paul to the Corinthians 19.7; on 1 Cor 7:35; in Oden, ibid., p. 72)

St. Augustine

Go on in your course, and run with perseverance [in the unmarried state devoted to God], in order that ye may obtain; and by pattern of life, and discourse of exhortation, carry away with you into this same your course, whomsoever ye shall have had power. Let there not bend you from this earnest purpose, whereby ye excite many to follow, the complaint of vain persons, who say, How shall the human race subsist, if all shall have been continent? As though it were for any other reason that this world is delayed, save that the predestined number of the Saints be fulfilled, and were this the sooner fulfilled, assuredly the end of the world would not be put off. Nor let it stay you from your earnest purpose of persuading others to the same good ye have, if it be said to you, Whereas marriage also is good, how shall there be all goods in the Body of Christ, both the greater, forsooth, and the lesser, if all through praise and love of continence imitate? In the first place, because with the endeavor that all be continent, there will still be but few, for “not all receive this word.” But forasmuch as it is written, “He who can receive, let him receive;” then do they receive who can, when silence is not kept even toward those who cannot. Next, neither ought we to fear lest haply all receive it, and some one of lesser goods, that is, married life, be wanting in the body of Christ. For if all shall have heard, and all shall have received, we ought to understand that this very thing was predestined, that married goods already suffice in the number of those members which so many have passed out of this life. … Therefore all these goods will have there their place, although from this time no woman wish to be married, no man wish to marry a wife. Therefore without anxiety urge on whom ye can, to become what ye are; and pray with watchfulness and fervor, that by the help of the Right Hand of the Most High, and by the abundance of the most merciful grace of the Lord, ye may both persevere in that which ye are, and may make advances unto that which ye shall be. (On the Good of Widowhood)

There are also vows proper for individuals: one vows to God conjugal chastity, that he will know no other woman besides his wife: so also the woman, that she will know no other man besides her husband. Other men also vow, even though they have used such a marriage, that beyond this they will have no such thing, that they will neither desire nor admit the like: and these men have vowed a greater vow than the former. Others vow even virginity from the beginning of life, that they will even know no such thing as those who having experienced have relinquished: and these men have vowed the greatest vow. Others vow that their house shall be a place of entertainment for all the Saints that may come: a great vow they vow. Another vows to relinquish all his goods to be distributed to the poor, and go into a community, into a society of the Saints: a great vow he doth vow. “Vow ye, and pay to the Lord our God.” Let each one vow what he shall have willed to vow; let him give heed to this, that he pay what he hath vowed. If any man doth look back with regard to what he hath vowed to God, it is an evil. . . .

One thing is done by thy profession, another thing will be perfected by the aid of God. Look to Him who doth guide thee, and thou wilt not look back to the place whence He is leading thee forth. (Exposition on Psalm 76)

It’s very easy to make false claims; much more difficult to prove them, isn’t it? Calvin excels at eloquent claims and flowery rhetoric. He does far less well in documenting and proving his various claims. It’s an elementary rule in debate: to not make sweeping negative statements (“no one ever did so-and-so”; “the fathers never taught thus-and-so”; “x is always the case in Scripture”; etc.). The reason this is unwise is because it can so easily be shot down, even by one counter-example. The more counter-examples that can be produced, the sillier and more foolish the person looks who made the now-refuted negative claim. It is shown to be empty rhetoric. The person clearly didn’t do his homework.

The present instance is a classic example of this failing. Calvin certainly knew enough to know better. But because his purpose was polemical propaganda, apparently he simply didn’t care; knowing that most of his readers wouldn’t bother to check and see if his extravagant claims about Church history were accurate or not. Most wouldn’t have had the resources to do it even if they wished to. But now with the Internet and the free availability of books, it is easy as pie to put the lie to one of Calvin’s many historical and biblical whoppers.

And the very things which these worthy expounders pretend that Christ only counselled they uniformly declare, without any doubt, that he expressly enjoined. But as we have shown above,

Where? I didn’t see it . . .

that this is a most pestilential error, let it suffice here to have briefly observed that monasticism, as it now exists, founded on an idea which all pious men ought to execrate—namely, the pretence that there is some more perfect rule of life than that common rule which God has delivered to the whole Church. Whatever is built on this foundation cannot but be abominable.

Since the foundation is plainly, explicitly biblical, and strongly affirmed by the fathers (contra Calvin’s claims to the contrary), it is Calvin’s foundation that is “abominable” and that must be discarded. He has amply refuted himself, hanging himself on his own untrue assertions. Calvin makes my job easy, when he wants to act this foolishly. Certainly many more relevant Bible passages could be brought to bear, but we don’t want to pile on too much. For example, 1 Corinthians 12:31: “But earnestly desire the higher gifts.”

*

But they produce another argument for their perfection, and deem it invincible. Our Lord said to the young man who put a question to him concerning the perfection of righteousness, “If thou wilt be perfect, go and sell that thou hast, and give to the poor” (Mt. 19:21). Whether they do so, I do not now dispute. Let us grant for the present that they do. They boast, then, that they have become perfect by abandoning their all. If the sum off perfection consists in this, what is the meaning of Paul’s doctrine, that though a man should give all his goods to feed the poor, and have not charity, he is nothing? (1 Cor. 13:3).

Obviously our Lord presupposed that love would be present also. But that doesn’t nullify the Lord’s point to the rich young ruler. It merely expands it. More “either/or” fallacies . . .

What kind of perfection is that which, if charity be wanting, is with the individual himself reduced to nothing? Here they must of necessity answer that it is indeed the highest, but is not the only work of perfection. But here again Paul interposes; and hesitates not to declare that charity, without any renunciation of that sort, is the “bond of perfectness” (Col. 3:14). If it is certain that there is no disagreement between the scholar and the master, and the latter clearly denies that the perfection of a man consists in renouncing all his goods, and on the other hand asserts that perfection may exist without it, we must see in what sense we should understand the words of Christ, “If thou wilt be perfect, go and sell that thou hast.” Now, there will not be the least obscurity in the meaning if we consider (this ought to be attended to in all our Saviour’s discourses) to whom the words are addressed (Luke 10:25). A young man asks by what works he shall enter into eternal life. Christ, as he was asked concerning works, refers him to the law. And justly; for, considered in itself, it is the way of eternal life, and its inefficacy to give eternal life is owing to our depravity. By this answer Christ declared that he did not deliver any other rule of life than that which had formerly been delivered in the law of the Lord. Thus he both bore testimony to the divine law, that it was a doctrine of perfect righteousness, and at the same time met the calumnious charge of seeming, by some new rule of life, to incite the people to revolt from the law. The young man, who was not ill-disposed, but was puffed up with vain confidence, answers that he had observed all the precepts of the law from his youth. It is absolutely certain that he was immeasurably distant from the goal which he boasted of having reached. Had his boast been true, he would have wanted nothing of absolute perfection. For it has been demonstrated above, that the law contains in it a perfect righteousness. This is even obvious from the fact, that the observance of it is called the way to eternal life. To show him how little progress he had made in that righteousness which he too boldly answered that he had fulfilled, it was right to bring before him his besetting sin. Now, while he abounded in riches, he had his heart set upon them.

That is truly the key to the passage. He had made riches his idol, which is why for him, it was necessary to renounce wealth in order to be saved. That is a little different from voluntarily renouncing wealth. The latter does not presuppose an inordinate attachment to it, let alone bondage or idolatry.

Therefore, because he did not feel this secret wound, it is probed by Christ—“Go,” says he, “and sell that thou hast.” Had he been as good a keeper of the law as he supposed, he would not have gone away sorrowful on hearing these words. For he who loves God with his whole heart, not only regards everything which wars with his love as dross, but hates it as destruction (Phil. 3:8). Therefore, when Christ orders a rich miser to leave all that he has, it is the same as if he had ordered the ambitious to renounce all his honours, the voluptuous all his luxuries, the unchaste all the instruments of his lust. Thus consciences, which are not reached by any general admonition, are to be recalled to a particular feeling of their particular sin. In vain, therefore, do they wrest that special case to a general interpretation, as if Christ had decided that the perfection of man consists in the abandonment of his goods, since he intended nothing more by the expression than to bring a youth who was out of measure satisfied with himself to feel his sore, and so understand that he was still at a great distance from that perfect obedience of the law which he falsely ascribed to himself.

Calvin has a certain point here, that I agree with. This passage is only a partial analogy to the notion of the evangelical counsels. The better passages to bring to bear are 1 Corinthians 7 and Matthew 19. These refer to voluntarily celibacy for the sake of the kingdom. That’s a call above and beyond the ordinary, and a disproof of Calvin’s denial of same, as are the many passages in St. Paul where the apostle describes his voluntary deprivations and sacrifices. It is a higher calling: a more perfected life. He even calls himself a “libation” (Philippians 2:17) and refers to “my sufferings for your sake” (Colossians 1:24).

Paul’s life was clearly not for everyone. Therefore, there is indeed such a thing as the counsels of perfection. It is utterly obvious that St. Paul was closer to it than Calvin or myself or most people who have not completely devoted themselves to the work of the kingdom. The early Christians owned everything in common; Jesus told His disciples to take very little with them when they went out evangelizing, etc.

I admit that this passage was ill understood by some of the Fathers; and hence arose an affectation of voluntary poverty, those only being thought blest who abandoned all earthly goods, and in a state of destitution devoted themselves to Christ.

Didn’t Paul pretty much do that? Didn’t the disciples leave everything to follow Jesus? Why would anyone want to denigrate and “demote” such extraordinary devotion?

But I am confident that, after my exposition, no good and reasonable man will have any dubiety here as to the mind of Christ.

I seek the mind of Christ; I don’t see it here expressed in Calvin’s revolutionary denials of what had always been patently obvious in the Catholic Church, based on numerous scriptural warrants. He made one decent point about the rich young ruler, but that by no means exhausts the Catholic proofs in defense of our belief in the evangelical counsels.

Still there was nothing with the Fathers less intended than to establish that kind of perfection which was afterwards fabricated by cowled monks, in order to rear up a species of double Christianity.

That’s not what we observed above, when I cited several fathers (even some of the most eminent ones) contra Calvin.

For as yet the sacrilegious dogma was not broached which compares the profession of monasticism to baptism, nay, plainly asserts that it is the form of a second baptism. Who can doubt that the Fathers with their whole hearts abhorred such blasphemy?

It is another means of grace. One might compare it to a further infilling of the spirit. Nothing in that is unscriptural. What is blatantly unscriptural, however, is Calvin’s denial that the first baptism regenerates. This is contrary to several clear Bible passages and the unanimous consensus of the fathers. A web page describing Benedictine spirituality touched upon the meaning of “second baptism” (italics added):

Although the Rule of Benedict does not use the word “conversion,” the idea was prominent in ancient monasticism, which saw monastic profession as “a second baptism” and a sharing in the dying and rising of Christ. ” Personal conversion is at the heart of every vocation, particularly the monastic calling, which is a specific form of putting of the “old man,” and being clothed with Christ.

In the Hebrew Old Testament, the word for conversion was “shub,” which means “to turn,” and could be used in he sense of “turning one’s life around” (e.g., Is 6.10). The same verb also can mean “turning again” or “returning,” “reversal” (Ps 51.13; Is 55.7). God (re)turns toward his people with a new attitude when they turn to him (Ps 85.1-3; Deut 13.17; Hos 11). The word “shub” is not used frequently, but the prophets speak often o the need for a change of heart, a conversion (Is 44.21b-22; 45.22;). The heart of conversion is to turn away from sin and turn toward God.

In the New Testament the word “conversion” (epistrophe) appears only in Acts 15.3, but more frequent is the word “change of heart/mind” (metanoia). The Kingdom of God, announced and inaugurated by and in Jesus, requires a radical conversion. The initial proclamation of John the Baptist and Jesus calls for a change of heart (Mk 1.8, 15 and parallels), a concept which is very akin to repentance. The apostles’ preaching also called for such a change of heart (Acts 2.38-39), and the Acts are full of stories of conversion (2.5-47 [crowds at Pentecost]. 8.26-39 [Ethiopian eunuch], 9.1-22 [Paul], 16.27-34 [jailor at Philippi]. Those who convert hear the word, are open and accept it, their change of heart Is expressed in ritual and in their transformed lives. Conversion is, in fact, a lifelong process by which one is transformed into the image of God (2 Cor 3.18).

Then what need is there to demonstrate, by words, that the last quality which Augustine mentions as belonging to the ancient monks—viz. that they in all things accommodated themselves to charity—is most alien from this new profession? The thing itself declares that all who retire into monasteries withdraw from the Church. For how? Do they not separate themselves from the legitimate society of the faithful, by acquiring for themselves a special ministry and private administration of the sacraments? What is meant by destroying the communion of the Church if this is not?

This is absurd. The Church (and the Bible) recognizes that different people in the Body of Christ have different callings and gifts (1 Corinthians 7:17; chapter 12). Therefore, if some feel called to be celibate and lead a life of prayer in relative isolation, that is not a withdrawal from the Church; rather, it is serving the Church by concentrating on certain very important elements of spirituality.

Protestants don’t describe missionaries who go off into the wilds into a completely non-Christian environment a separation “from the legitimate society of the faithful”! Why should it be different with those who devote themselves to prayer? Of course, if prayer is derided as of no import, it might be different, but I don’t think Calvin wishes to argue that. He ought to reconsider the foolishness of condemnations like these, then.

Some of these “isolated” monks that Calvin is so alarmed about devoted their entire lives to copying biblical manuscripts, so that Calvin could even have a Bible at all to work with and from. Would he condemn that, too, because they were relatively isolated? I doubt it. Therefore, his objection collapses because of the absurdity of its consequences fully considered.

And to follow out the comparison with which I began, and at once close the point, what resemblance have they in this respect to the ancient monks? These, though they dwelt separately from others, had not a separate Church; they partook of the sacraments with others, they attended public meetings, and were then a part of the people.

The desert or “hermit” monks in the tradition of St. Anthony were not. Nor were there no notable figures among the fathers who took this approach to spirituality:

Very many of them were saints. Doctors of the Church, like St. Basil, St. Gregory of Nazianzus, St. John Chrysostom, St. Jerome, belonged to their number; and we might also mention Sts. Epiphanius, Ephraem, Hilarion, Nilus, Isidore of Pelusium. (The Catholic Encyclopedia, “Hermits”)

Yet here comes Calvin, telling us that the tradition is not ancient. Go figure . . . The same article describes the various interpretations of “solitude” — there were hermits who were absolutely isolated, but the majority had some sort of community connection (at least in a monastic community). So the Church had long since dealt with the question of the relation between the two. Calvin brings up nothing new.

But what have those men done in erecting a private altar for themselves but broken the bond of unity? For they have excommunicated themselves from the whole body of the Church, and contemned the ordinary ministry by which the Lord has been pleased that peace and charity should be preserved among his followers. Wherefore I hold that as many monasteries as there are in the present day, so many conventicles are there of schismatics, who have disturbed ecclesiastical order, and been cut off from the legitimate society of the faithful.

A Protestant like Calvin bringing up schism and wrongly applying it to the monastic life is as ironic and amusing as a fish condemning the water that he lives in or a tiger coming out against a carnivorous diet (or a lumberjack sawing off the limb he is sitting on).

And that there might be no doubt as to their separation, they have given themselves the various names of factions.

Factions? Orders are not denominations. We all know where that difficulty is present.

They have not been ashamed to glory in that which Paul so execrates, that he is unable to express his detestation too strongly. Unless, indeed, we suppose that Christ was not divided by the Corinthians, when one teacher set himself above another (1 Cor. 1:12, 13; 3:4); and that now no injury is done to Christ when, instead of Christians, we hear some called Benedictines, others Franciscans, others Dominicans, and so called, that while they affect to be distinguished from the common body of Christians, they proudly substitute these names for a religious profession.

Calvinists, Lutherans, Anabaptists, Anglicans, Zwinglians . . . and that is only within Calvin’s lifetime. It gets much worse after that. Catholic orders are merely different methods of approaching the spiritual life. Where they do take different theological views, it is in areas of permissible disagreement, such as the relationship of reason and faith, or predestination and free will. With Protestant denominations, on the other hand, massive doctrinal relativism is inherent, and the early Protestants often anathematized each other. Luther thought Zwingli was damned, and vice versa, etc. Calvin once described Lutheranism as an “evil.”

The differences which I have hitherto pointed out between the ancient monks and those of our age are not in manners, but in profession. Hence let my readers remember that I have spoken of monachism rather than of monks; and marked, not the vices which cleave to a few, but vices which are inseparable from the very mode of life.

All is extreme in Calvin . . . no grey areas or fine distinctions for him when it comes to alleged universal Catholic corruption.

In regard to manners, of what use is it to particularise and show how great the difference? This much is certain, that there is no order of men more polluted by all kinds of vicious turpitude; nowhere do faction, hatred, party-spirit, and intrigue, more prevail.

Yet they managed to do quite a bit of societal good, for all that corruption (even granting for a second that Calvin’s ludicrous depiction is true).

In a few monasteries, indeed, they live chastely, if we are to call it chastity, where lust is so far repressed as not to be openly infamous;

Thank you Calvin for the small favor and bow to reality.

still you will scarcely find one in ten which is not rather a brothel than a sacred abode of chastity. But how frugally they live? Just like swine wallowing in their sties.

Detest the sin and reform the sinner where they are found, but don’t throw out entire institutions and doctrines because of sin, because that is plain stupid and completely unnecessary.

But lest they complain that I deal too unmercifully with them, I go no farther; although any one who knows the case will admit, that in the few things which I have said, I have not spoken in the spirit of an accuser. Augustine though he testifies, that the monks excelled so much in chastity, yet complains that there were many vagabonds, who, by wicked arts and impostures, extracted money from the more simple, plying a shameful traffic, by carrying about the relics of martyrs, and vending any dead man’s bones for relics, bringing ignominy on their order by many similar iniquities.

Augustine, of course, was not against the notion of relics altogether, as seems to be implied here.

As he declares that he had seen none better than those who had profited in monasteries; so he laments that he had seen none worse than those who had backslidden in monasteries. What would he say were he, in the present day, to see now almost all monasteries overflowing, and in a manner bursting, with numerous deplorable vices? I say nothing but what is notorious to all; and yet this charge does not apply to all without a single exception; for, as the rule and discipline of holy living was never so well framed in monasteries as that there were not always some drones very unlike the others; so I hold that, in the present day, monks have not so completely degenerated from that holy antiquity as not to have some good men among them; but these few lie scattered up and down among a huge multitude of wicked and dishonest men, and are not only despised, but even petulantly assailed, sometimes even treated cruelly by the others, who, according to the Milesian proverb, think they ought to have no good man among them.

Truly good, saintly men are always persecuted; nothing new there. But we are thankful that Calvin recognizes any good whatever in any Catholic. No doubt he probably thinks that the “good men” would immediately become Protestants as soon as they heard his glorious teachings. This mentality is often present in Calvin’s followers today: the only “good” Catholic is the “bad Catholic”: i.e., the one who disagrees with all the Catholic doctrines that he should disbelieve (per Protestantism).

*

By this contrast between ancient and modern monasticism, I trust I have gained my object, which was to show that our cowled monks falsely pretend the example of the primitive Church in defence of their profession; since they differ no less from the monks of that period than apes do from men.

Even from the facts I have presented above, the actual truth would seem to be quite otherwise. Calvin always wants to set forth the pretense that Calvinism more closely resembles the early Church than the Catholicism of his day did. But every time the historical particulars are examined, such an assertion fall flat: contradicted at every turn.

Meanwhile I disguise not that even in that ancient form which Augustine commends, there was something which little pleases me.

Why should anyone care what “pleases” Calvin or not? Who is he to assume that people should be overwhelmingly concerned with his dogmatic, arbitrary opinions? This is one of the premises assumed and not thought about in Protestantism, that is rarely discussed: the self-proclaimed arbitrary authority of its leaders. Basically whoever had the biggest mouth or was most eloquent in smearing Catholics, was regarded as a leader. In England, the leader was the king who simply assumed power, called himself the head of the church, and started killing people who disagreed (scarcely different from the Leninists, Stalinists, and Maoists of the illustrious 20th century).

I admit that they were not superstitious in the external exercises of a more rigorous discipline, but I say that they were not without a degree of affectation and false zeal.

Something that Calvin, of course, is entirely free of . . .

It was a fine thing to cast away their substance, and free themselves from all worldly cares;

A small but notable concession . . .

but God sets more value on the pious management of a household, when the head of it, discarding all avarice, ambition, and other lusts of the flesh, makes it his purpose to serve God in some particular vocation. It is fine to philosophise in seclusion, far away from the intercourse of society; but it ill accords with Christian meekness for any one, as if in hatred of the human race, to fly to the wilderness and to solitude, and at the same time desert the duties which the Lord has especially commanded. Were we to grant that there was nothing worse in that profession, there is certainly no small evil in its having introduced a useless and perilous example into the Church.

Answered above. By this silliness, Calvin also condemns John the Baptist, most of the prophets, and Protestant missionaries who go into strange heathen lands.

*

Now, then, let us see the nature of the vows by which the monks of the present day are initiated into this famous order. First, as their intention is to institute a new and fictitious worship with a view to gain favour with God,

What worship is that, pray tell? Conveniently, no details are given.

I conclude from what has been said above, that everything which they vow is abomination to God.

Then he concludes wrongly.

Secondly, I hold that as they frame their own mode of life at pleasure, without any regard to the calling of God, or to his approbation,

No regard to calling at all? That’s odd . . .

the attempt is rash and unlawful; because their conscience has no ground on which it can support itself before God; and “whatsoever is not of faith is sin” (Rom. 14:23).

Everything is wrapped up in a neat little package. But as the premises are dead wrong so are the conclusions built upon them.

Moreover, I maintain that in astricting themselves to many perverse and impious modes of worship, such as are exhibited in modern monasticism, they consecrate themselves not to God but to the devil.

Ah! The logical conclusion of the critique based on radically wrong premises . . .

For why should the prophets

That is, the very ones who were often isolated (by God’s call) in a way that Calvin condemned . . .

have been permitted to say that the Israelites sacrificed their sons to devils and not to God (Deut. 32:17; Ps. 106:37), merely because they had corrupted the true worship of God by profane ceremonies; and we not be permitted to say the same thing of monks who, along with the cowl, cover themselves with the net of a thousand impious superstitions?

So now a Catholic monk is the equivalent of an abortionist or a Nazi. How quaint . . .

Then what is their species of vows? They offer God a promise of perpetual virginity, as if they had previously made a compact with him to free them from the necessity of marriage.

If God calls them to it (1 Cor 7; Matthew 19), then it is altogether proper for them to make such a vow. It is simply obedience to God’s will. But as Jesus said, not all men can “receive” this teaching.

They cannot allege that they make this vow trusting entirely to the grace of God; for, seeing he declares this to be a special gift not given to all (Mt. 19:11), no man has a right to assume that the gift will be his.

If the gift is present to some, what sense does it make that none to whom the gift is given can discern it? What God desires, He makes known to the men included in the plan which He has ordained. Otherwise, it is senseless to bring up the topic at all. There are such things as eunuchs for the kingdom’s sake, yet no one can figure out if he is one? What sense does that make?

Because the gift is not for all, therefore, no one can possibly know that he is of the group that is the exception, and cannot possibly make a vow, sincerely, in faith, trusting God? How in the world does that follow? This is convoluted argumentation and sophistry at its goofiest. One could have a discussion with a snapping turtle and it would be more logical and productive of insight than this tomfoolery that makes no sense at all.

Let those who have it use it; and if at any time they feel the infirmity of the flesh, let them have recourse to the aid of him by whose power alone they can resist.

It is not impossible to vow to be celibate. If it were so, every unmarried man must necessarily be a fornicator, since he is utterly unable to be chaste, even with God’s help. If a young man at the height of his sexual desire can remain sexually pure with God’s help, before he is married, why can’t an older monk to do the same thing? If one thing is possible, so is the other, all the more so, and especially since God promises that we can do all things by His strength. But if one lacks faith in God’s power and promises, then one arrives at doctrines such as what Calvin spouts: a wholesale denigration of celibacy and monasticism.

If this avails not, let them not despise the remedy which is offered to them. If the faculty of continence is denied, the voice of God distinctly calls upon them to marry.

No one is denying this, so it is a moot point.

By continence I mean not merely that by which the body is kept pure from fornication, but that by which the mind keeps its chastity untainted. For Paul enjoins caution not only against external lasciviousness, but also burning of mind (1 Cor. 7:9). It has been the practice (they say) from the remotest period, for those who wished to devote themselves entirely to God, to bind themselves by a vow of continence. I confess that the custom is ancient, but I do not admit that the age when it commenced was so free from every defect that all that was then done is to be regarded as a rule. Moreover, the inexorable rigour of holding that after the vow is conceived there is no room for repentance, crept in gradually.

For Catholics, a vow is a vow. I know that this may be a bizarre novelty for Calvin, but it is not a novelty in terms of biblical teaching. Even today, there is some semblance left of the high importance and binding nature of vows, in marital vows. Calvin simply doesn’t have enough faith to grasp that a man could be called to a life of celibacy in service to God, know that he is so called (somewhat like how we “know” that we are “called” to marry a particular person), and thus, be able to make the vow.

This is clear from Cyprian. “If virgins have dedicated themselves to Christian faith, let them live modestly and chastely, without pretence. Thus strong and stable, let them wait for the reward of virginity. But if they will not, or cannot persevere, it is better to marry, than by their faults to fall into the fire.”

Of course. Who disagrees? This is simply the application of 1 Corinthians 7.

In the present day, with what invectives would they not lacerate any one who should seek to temper the vow of continence by such an equitable course? Those, therefore, have wandered far from the ancient custom who not only use no moderation, and grant no pardon when any one proves unequal to the performance of his vow, but shamelessly declare that it is a more heinous sin to cure the intemperance of the flesh by marriage, than to defile body and soul by whoredom.

These are sins. If a monk or priest declares that he wrongly took a vow, then he can be dismissed from the priesthood or the religious life. Thus, “exceptions” can be dealt with individually. This is no disproof of the entire lifestyle: that some abuse it. There have been fake Protestant evangelists who were only in it for the money (Marjoe Gortner was a famous example in our times). Does that mean there are no real evangelists? Of course not. Yet this is how Calvin reasons: “there is corruption; indeed widespread corruption; therefore the thing itself is illegitimate, wicked through and through; of the devil.”

But they still insist and attempt to show that this vow was used in the days of the apostles, because Paul says that widows who marry after having once undertaken a public office, “cast off their first faith” (1 Tim. 5:12). I by no means deny that widows who dedicated themselves and their labours to the Church, at the same time came under an obligation of perpetual celibacy, not because they regarded it in the light of a religious duty, as afterwards began to be the case, but because they could not perform their functions unless they had their time at their own command, and were free from the nuptial tie. But if, after giving their pledge, they began to look to a new marriage, what else was this but to shake off the calling of God?

Obviously, we ought not shake off the calling of God. We should follow it, whatever it is. I’m following mine, in writing this critique! I’m an apologist. I’ve known that this was my calling since 1981. God gives the desire and ability to do what He calls one to do. I’ve never felt the call to be celibate, so I’m not (very happily married: for 25 years, exactly two weeks from this writing). Why does this have to be so complicated? I don’t think it’s rocket science to figure out. But Calvin goes in and on, embroiled in his anti-Catholic fallacies.

It is not strange, therefore, when Paul says that by such desires they grow wanton against Christ. In further explanation he afterwards adds, that by not performing their promises to the Church, they violate and nullify their first faith given in baptism; one of the things contained in this first faith being, that every one should correspond to his calling. Unless you choose rather to interpret that, having lost their modesty, they afterwards cast off all care of decency, prostituting themselves to all kinds of lasciviousness and pertness, leading licentious and dissolute lives, than which nothing can less become Christian women.

No one disagrees that sexual sin is wrong. There is no discussion necessary on that.

I am much pleased with this exposition. Our answer then is, that those widows who were admitted to a public ministry came under an obligation of perpetual celibacy, and hence we easily understand how, when they married, they threw off all modesty, and became more insolent than became Christian women that in this way they not only sinned by violating the faith given to the Church, but revolted from the common rule of pious women. But, first, I deny that they had any other reason for professing celibacy than just because marriage was altogether inconsistent with the function which they undertook. Hence they bound themselves to celibacy only in so far as the nature of their function required.

If someone is called to it, they will be given the strength and desire to do it. Many thousands of priests and religious are living examples of that. Calvin lived in a far more corrupt time (we freely grant this). But that doesn’t change the biblical and spiritual principles involved.

Secondly, I do not admit that they were bound to celibacy in such a sense that it was not better for them to marry than to suffer by the incitements of the flesh, and fall into uncleanness. Thirdly, I hold that what Paul enjoined was in the common case free from danger, because he orders the selection to be made from those who, contented with one marriage, had already given proof of continence. Our only reason for disapproving of the vow of celibacy is, because it is improperly regarded as an act of worship, and is rashly undertaken by persons who have not the power of keeping it.

We agree with that, but obviously this does not take in every conceivable case, so it is an incomplete analysis; a sort of half-truth.

But what ground can there be for applying this passage to nuns? For deaconesses were appointed, not to soothe God by chantings or unintelligible murmurs, and spend the rest of their time in idleness; but to perform a public ministry of the Church toward the poor, and to labour with all zeal, assiduity, and diligence, in offices of charity. They did not vow celibacy, that they might thereafter exhibit abstinence from marriage as a kind of worship rendered to God, but only that they might be freer from encumbrance in executing their office.

It is a partial analogy, not a complete one.

In fine, they did not vow on attaining adolescence, or in the bloom of life, and so afterwards learn, by too late experience, over what a precipice they had plunged themselves, but after they were thought to have surmounted all danger, they took a vow not less safe than holy. But not to press the two former points, I say that it was unlawful to allow women to take a vow of continence before their sixtieth year, since the apostle admits such only, and enjoins the younger to marry and beget children. Therefore, it is impossible, on any ground, to excuse the deduction, first of twelve, then of twenty, and, lastly, of thirty years. Still less possible is it to tolerate the case of miserable girls, who, before they have reached an age at which they can know themselves, or have any experience of their character, are not only induced by fraud, but compelled by force and threats, to entangle themselves in these accursed snares.

Obviously a forced or improperly thought-through vow is undesirable and foolish.

I will not enter at length into a refutation of the other two vows. This only I say, that besides involving (as matters stand in the present day) not a few superstitions, they seem to be purposely framed in such a manner, as to make those who take them mock God and men.

Yes! It’s obviously a diabolical conspiracy! Who could doubt it?

But lest we should seem, with too malignant feeling, to attack every particular point, we will be contented with the general refutation which has been given above.

How gracious and restrained . . .

The nature of the vows which are legitimate and acceptable to God, I think I have sufficiently explained. Yet, because some ill-informed and timid consciences, even when a vow displeases, and is condemned, nevertheless hesitate as to the obligation, and are grievously tormented, shuddering at the thought of violating a pledge given to God, and, on the other hand, fearing to sin more by keeping it,—we must here come to their aid, and enable them to escape from this difficulty. And to take away all scruple at once, I say that all vows not legitimate, and not duly conceived, as they are of no account with God, should be regarded by us as null. (See Calv. ad Concil. Trident.)

The same is true of marriage, which is why there is such a thing as an annulment, and it is based on biblical teaching.

For if, in human contracts, those promises only are binding in which he with whom we contract wishes to have us bound, it is absurd to say that we are bound to perform things which God does not at all require of us, especially since our works can only be right when they please God, and have the testimony of our consciences that they do please him. For it always remains fixed, that “whatsoever is not of faith is sin” (Rom. 14:23). By this Paul means, that any work undertaken in doubt is vicious, because at the root of all good works lies faith, which assures us that they are acceptable to God. Therefore, if Christian men may not attempt anything without this assurance, why, if they have undertaken anything rashly through ignorance, may they not afterwards be freed, and desist from their error?

Sometimes they are. But a rash vow does not disprove the existence of all legitimate vows. And if vows are too easily dissolved, then the serious nature of vows is undermined

Since vows rashly undertaken are of this description, they not only oblige not, but must necessarily be rescinded. What, then, when they are not only of no estimation in the sight of God, but are even an abomination, as has already been demonstrated? It is needless farther to discuss a point which does not require it. To appease pious consciences, and free them from all doubt, this one argument seems to me sufficient—viz. that all works whatsoever which flow not from a pure fountain, and are not directed to a proper end, are repudiated by God, and so repudiated, that he no less forbids us to continue than to begin them. Hence it follows, that vows dictated by error and superstition are of no weight with God, and ought to be abandoned by us.

We can agree that vows need to be taken only following a great deal of reflection, counsel, and prayer.

21. Those who abandon the monastic profession for an honest living, unjustly accused of breaking their faith.

*

Note the seething scorn of the title . . .

He who understands this solution is furnished with the means of repelling the calumnies of the wicked against those who withdraw from monasticism to some honest kind of livelihood.

Therefore, it follows that monks are dishonest by nature and/or don’t work . . . how often I have also heard this charge with regard to the vocation of apologetics!

They are grievously charged with having perjured themselves, and broken their faith, because they have broken the bond (vulgarly supposed to be indissoluble) by which they had bound themselves to God and the Church. But I say, first, there is no bond when that which man confirms God abrogates; and, secondly, even granting that they were bound when they remained entangled in ignorance and error, now, since they have been enlightened by the knowledge of the truth, I hold that they are, at the same time, free by the grace of Christ.

In other words, all monks are ignoramuses, unacquainted with the rudimentary elements of Christianity and with God Himself, therefore all vows are null and void. The “grace of Christ” trumps all self-imposed obligations undertaken in good faith. This is how the so-called “reformers” often reasoned. Take note.

For if such is the efficacy of the cross of Christ, that it frees us from the curse of the divine law by which we were held bound, how much more must it rescue us from extraneous chains, which are nothing but the wily nets of Satan?

Catholicism being the wicked religion that it is . . .

There can be no doubt, therefore, that all on whom Christ shines with the light of his Gospel, he frees from all the snares in which they had entangled themselves through superstition.

I could see this rationale being used in divorce court . . .

At the same time, they have another defence if they were unfit for celibacy. For if an impossible vow

Who says it is impossible? Many biblical examples refute this.

is certain destruction to the soul, which God wills to be saved and not destroyed, it follows that it ought by no means to be adhered to. Now, how impossible the vow of continence is to those who have not received it by special gift, we have shown, and experience, even were I silent, declares: while the great obscenity with which almost all monasteries teem is a thing not unknown.

But now Calvin is talking out of both sides of his mouth. It’s possible for some to be chaste, but the whole system is of the devil and superstition, anyway, so it doesn’t matter. Therefore, even the most observant, conscientious, “good” monk is a servant of Satan and a dupe, whether he knows it or not. Marvelously charitable judgments, aren’t they?

If any seem more decent and modest than others, they are not, however, chaste.

Case in point . . .

The sin of unchastity urges, and lurks within.

Just as the sin of rebellion and schism and spiritual pride and slander lurks within certain folks . . .

Thus it is that God, by fearful examples, punishes the audacity of men, when, unmindful of their infirmity, they, against nature, affect that which has been denied to them, and despising the remedies which the Lord has placed in their hands, are confident in their ability to overcome the disease of incontinence by contumacious obstinacy. For what other name can we give it, when a man, admonished of his need of marriage, and of the remedy with which the Lord has thereby furnished, not only despises it, but binds himself by an oath to despise it?

More of the same conclusions based on false premises . . .we don’t throw out the baby with the dirty bathwater. We discard the bad thing and keep the good thing.

(originally 9-22-09)

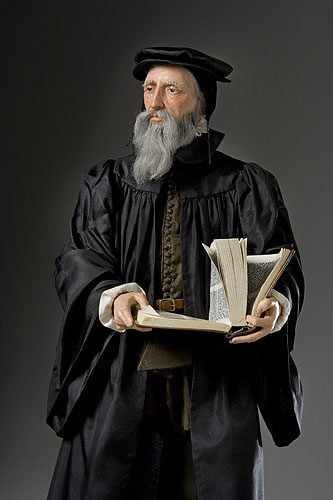

Photo credit: Historical mixed media figure of John Calvin produced by artist/historian George S. Stuart and photographed by Peter d’Aprix: from the George S. Stuart Gallery of Historical Figures archive [Wikimedia Commons / Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license]

***