This is an installment of a series of replies (see the Introduction and Master List) to much of Book IV (Of the Holy Catholic Church) of Institutes of the Christian Religion, by early Protestant leader John Calvin (1509-1564). I utilize the public domain translation of Henry Beveridge, dated 1845, from the 1559 edition in Latin; available online. Calvin’s words will be in blue. All biblical citations (in my portions) will be from RSV unless otherwise noted.

Related reading from yours truly:

Biblical Catholic Answers for John Calvin (2010 book: 388 pages)

A Biblical Critique of Calvinism (2012 book: 178 pages)

Biblical Catholic Salvation: “Faith Working Through Love” (2010 book: 187 pages; includes biblical critiques of all five points of “TULIP”)

*****

IV, 17:29-30

***

CHAPTER 17

OF THE LORD’S SUPPER, AND THE BENEFITS CONFERRED BY IT.

*

*

Since they put so much confidence in his hiding-place of invisible presence, let us see how well they conceal themselves in it.

Okay; let’s.

First, they cannot produce a syllable from Scripture to prove that Christ is invisible;

Is Calvin serious? That’s rather easy:

Matthew 18:20 For where two or three are gathered in my name, there am I in the midst of them.

Matthew 28:20 teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you; and lo, I am with you always, to the close of the age.

John 14:20 In that day you will know that I am in my Father, and you in me, and I in you.

John 14:23 Jesus answered him, “If a man loves me, he will keep my word, and my Father will love him, and we will come to him and make our home with him.”

John 15:4 Abide in me, and I in you. As the branch cannot bear fruit by itself, unless it abides in the vine, neither can you, unless you abide in me.

John 17:23 I in them and thou in me, that they may become perfectly one, so that the world may know that thou hast sent me and hast loved them even as thou hast loved me.

Romans 8:9-10 But you are not in the flesh, you are in the Spirit, if in fact the Spirit of God dwells in you. Any one who does not have the Spirit of Christ does not belong to him. [10] But if Christ is in you, although your bodies are dead because of sin, your spirits are alive because of righteousness.

Ephesians 1:22-23 and he has put all things under his feet and has made him the head over all things for the church, [23] which is his body, the fulness of him who fills all in all.

Colossians 1:27 To them God chose to make known how great among the Gentiles are the riches of the glory of this mystery, which is Christ in you, the hope of glory.

Colossians 3:11 . . . Christ is all, and in all. (cf. Eph 4:6)

1 Peter 1:11 they inquired what person or time was indicated by the Spirit of Christ within them when predicting the sufferings of Christ and the subsequent glory.

Calvin says there is not one “syllable” about this in Scripture; I have produced eleven passages. Readers can select the most probable position of the two.

but they take for granted what no sound man will admit, that the body of Christ cannot be given in the Supper, unless covered with the mask of bread.

Obviously it is a different sort of presence than cannibalism.

This is the very point in dispute; so far is it from occupying the place of the first principle. And while they thus prate, they are forced to give Christ a twofold body, because, according to them, it is visible in itself in heaven, but in the Supper is invisible, by a special mode of dispensation.

Indeed. And how is this impossible for a God Who can do anything that is possible to do? God can change the substance of the bread and wine into His Body and Blood, just as He created all substance to begin with. God the Father was mostly invisible, but also became visible in various ways, before the incarnation, as I have shown from Scripture elsewhere. Jesus was present in His post-Resurrection appearances, but sometimes those who witnessed Him did not know it was Him. So He was “hidden.” “Let him who has eyes to see . . .” Why Calvin wishes to tie God’s hands and draw the line at this particular miracle is an inexplicable wonder to behold.

The beautiful consistency of this may easily be judged, both from other passages of Scripture, and from the testimony of Peter. Peter says that the heavens must receive, or contain Christ, till he come again (Acts 3:21).

But that verse has to be synthesized with all the ones above. If He is exclusively in heaven, as Calvin foolishly imagines, then how is He also “in” us (Jn 14:20, 23; 15:4; 17:23; Rom 8:10; Col 1:27; 1 Pet 1:11)? How is He constantly in our midst (Matt 18:20; 28:20)? How is He “in all” and how does He fill “all in all” (Eph 1:23; Col 3:11)? If Calvin were here I would love to hear His answers to those questions (assuming he would even condescend to waste his time with a poor deluded papist such as I). How much Scripture does he plan to ignore or explain away?

These men teach that he is in every place, but without form.

And that is because it is a biblical teaching: in His Divine Nature He is omnipresent (as seen in the above eleven passages). If Calvin denies this then He is either denying the divinity of Jesus or he is again exhibiting Nestorian confusion and heresy (two things that he himself denies). This is not all that difficult to understand or establish from Holy Scripture. What is the oddest thing about all of this, however, is that elsewhere in the Institutes Calvin shows that he does believe in some sense of omnipresence of Jesus (and directly contradicts his statements above, denying that Christ could be in any sense invisible after the ascension):

[A]s God, he cannot be in any respect said to grow, works always for himself, knows every thing, does all things after the counsel of his own will, and is incapable of being seen or handled. (Inst., II, 14:2)

Yet now when he futilely argues against the Holy Eucharist, he wants to deny the same thing that he asserted before (and in a later section), simply because Jesus ascended to heaven:

Another absurdity which they obtrude upon us—viz. that if the Word of God became incarnate, it must have been enclosed in the narrow tenement of an earthly body, is sheer petulance. For although the boundless essence of the Word was united with human nature into one person, we have no idea of any enclosing. The Son of God descended miraculously from heaven, yet without abandoning heaven; was pleased to be conceived miraculously in the Virgin’s womb, to live on the earth, and hang upon the cross, and yet always filled the world as from the beginning. (Inst., II, 12:4)

Certainly when Paul says of the princes of this world that they “crucified the Lord of glory” (1 Cor. 2:8), he means not that he suffered anything in his divinity, but that Christ, who was rejected and despised, and suffered in the flesh, was likewise God and the Lord of glory. In this way, both the Son of man was in heaven because he was also Christ; and he who, according to the flesh, dwelt as the Son of man on earth, was also God in heaven. For this reason, he is said to have descended from heaven in respect of his divinity, not that his divinity quitted heaven to conceal itself in the prison of the body, but because, although he filled all things, it yet resided in the humanity of Christ corporeally, that is, naturally, and in an ineffable manner. There is a trite distinction in the schools which I hesitate not to quote. Although the whole Christ is everywhere, yet everything which is in him is not everywhere. . . . our whole Mediator is everywhere . . . (Inst., IV, 17:30)

Thus, we observe an absurd scenario whereby Calvin thinks that Jesus “descended miraculously from heaven, yet without abandoning heaven” but that after He ascended to heaven He no longer “filled the world” or could be invisibly present (let alone invisibly). In other words, He must (to follow by “symmetrical logic” Calvin’s statement about the incarnation) abandon the world, and so cannot possibly be present in the Eucharist.

For, in order to exhort us to submission by his example, he shows, that when as God he might have displayed to the world the brightness of his glory, he gave up his right, and voluntarily emptied himself; that he assumed the form of a servant, and, contented with that humble condition, suffered his divinity to be concealed under a veil of flesh. (Inst., II, 13:2)

So Christ can come to us “concealed under a veil of flesh” but He cannot come “covered with the mask of bread” or “invisible, by a special mode of dispensation”? Why is one thing believed by Calvin to be actual, but the other denied and disbelieved? On what grounds are they distinguished? This is one reason why Catholics believe that the Eucharist is an extension of the principle of the incarnation. Somehow human flesh can at the same time be God, and a Divine Nature and Human Nature can be in one Man; therefore, what was once bread and wine can be the Body and Blood of Christ. Calvin condemns his own reasoning in this regard, when he writes:

For we must put far from us the heresy of Nestorius, who, presuming to dissect rather than distinguish between the two natures, devised a double Christ. (Inst., II, 14:4)

They say that it is unfair to subject a glorious body to the ordinary laws of nature.

First of all, Christ is not subject to the “ordinary laws of nature” because He is the Creator and Lord of nature in the first place:

Matthew 28:18 . . . All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me. [KJV: “power”]

Philippians 3:20-21 . . . the Lord Jesus Christ, [21] who will change our lowly body to be like his glorious body, by the power which enables him even to subject all things to himself.

*

Colossians 1:16-17 for in him all things were created, in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or principalities or authorities — all things were created through him and for him. [17] He is before all things, and in him all things hold together.

Hebrews 1:3 He reflects the glory of God and bears the very stamp of his nature, upholding the universe by his word of power. When he had made purification for sins, he sat down at the right hand of the Majesty on high,

1 Peter 3:22 who has gone into heaven and is at the right hand of God, with angels, authorities, and powers subject to him.

Therefore it is beyond silly to restrict Him in such a way now.

But this answer draws along with it the delirious dream of Servetus, which all pious minds justly abhor, that his body was absorbed by his divinity. I do not say that this is their opinion; but if it is considered one of the properties of a glorified body to fill all things in an invisible manner, it is plain that the corporeal substance is abolished, and no distinction is left between his Godhead and his human nature.

That is simply untrue, and it is inconsistent with Calvin’s own reasoning applied to the incarnation, as just shown. Jesus was God when He was born in Bethlehem. He remains God since the time He ascended and was glorified. Therefore, He is omnipresent now; that doesn’t cease! But Calvin seems to think that it did, and that it is strange to believe that Jesus could be invisibly present (a denial of the indwelling) or present under the special miraculous circumstance of the Holy Eucharist. His logic is thoroughly inconsistent and arbitrary.

Again, if the body of Christ is so multiform and diversified, that it appears in one place, and in another is invisible, where is there anything of the nature of body with its proper dimensions, and where is its unity?

Our Lord Jesus Christ’s Body was no ordinary Body when He took on human flesh, and it is no ordinary Body now that He has been resurrected and glorified. That trumps all of Calvin’s arbitrary limitations, that he can find nowhere in Scripture. And when he does on rare occasion in these discussions feebly attempt to argue from Scripture, he is immediately refuted by ten times or more Scripture than he was able to come up with. He can’t argue his points now against criticism, but his followers can do so.

Far more correct is Tertullian, who contends that the body of Christ was natural and real, because its figure is set before us in the mystery of the Supper, as a pledge and assurance of spiritual life (Tertull. Cont. Marc. Lib. 4).

Tertullian did not hold to Calvin’s eucharistic heresy. He was stating in this book (chapter XL), that there is no figure if Christ’s body were not real in the first place (over against Marcion’s heresy), not that “figure” means no physical body is in question, and the whole thing is spiritualized. Calvin always has to set one against the other, but Scripture and the fathers and Tertullian do not do that (but Calvin nonetheless cites them as if they do). Here is what Tertullian wrote, in context (the entire chapter):

Title: How the Steps in the Passion of the Saviour Were Predetermined in Prophecy. The Passover. The Treachery of Judas. The Institution of the Lord’s Supper. The Docetic Error of Marcion Confuted by the Body and the Blood of the Lord Jesus Christ.

In like manner does He also know the very time it behoved Him to suffer, since the law prefigures His passion. Accordingly, of all the festal days of the Jews He chose the passover. In this Moses had declared that there was a sacred mystery: “It is the Lord’s passover.” How earnestly, therefore, does He manifest the bent of His soul: “With desire I have desired to eat this passover with you before I suffer.” What a destroyer of the law was this, who actually longed to keep its passover! Could it be that He was so fond of Jewish lamb? But was it not because He had to be “led like a lamb to the slaughter; and because, as a sheep before her shearers is dumb, so was He not to open His mouth,” that He so profoundly wished to accomplish the symbol of His own redeeming blood? He might also have been betrayed by any stranger, did I not find that even here too He fulfilled a Psalm: “He who did eat bread with me hath lifted up his heel against me.” And without a price might He have been betrayed. For what need of a traitor was there in the case of one who offered Himself to the people openly, and might quite as easily have been captured by force as taken by treachery? This might no doubt have been well enough for another Christ, but would not have been suitable in One who was accomplishing prophecies. For it was written, “The righteous one did they sell for silver.” The very amount and the destination of the money, which on Judas’ remorse was recalled from its first purpose of a fee, and appropriated to the purchase of a potter’s field, as narrated in the Gospel of Matthew, were clearly foretold by Jeremiah: “And they took the thirty pieces of silver, the price of Him who was valued and gave them for the potter’s field.” When He so earnestly expressed His desire to eat the passover, He considered it His own feast; for it would have been unworthy of God to desire to partake of what was not His own. Then, having taken the bread and given it to His disciples, He made it His own body, by saying, “This is my body,” that is, the figure of my body. A figure, however, there could not have been, unless there were first a veritable body. An empty thing, or phantom, is incapable of a figure. If, however, (as Marcion might say,) He pretended the bread was His body, because He lacked the truth of bodily substance, it follows that He must have given bread for us. It would contribute very well to the support of Marcion’s theory of a phantom body, that bread should have been crucified! But why call His body bread, and not rather (some other edible thing, say) a melon, which Marcion must have had in lieu of a heart! He did not understand how ancient was this figure of the body of Christ, who said Himself by Jeremiah: “I was like a lamb or an ox that is brought to the slaughter, and I knew not that they devised a device against me, saying, Let us cast the tree upon His bread,” which means, of course, the cross upon His body. And thus, casting light, as He always did, upon the ancient prophecies, He declared plainly enough what He meant by the bread, when He called the bread His own body. He likewise, when mentioning the cup and making the new testament to be sealed “in His blood,” affirms the reality of His body. For no blood can belong to a body which is not a body of flesh. If any sort of body were presented to our view, which is not one of flesh, not being fleshly, it would not possess blood. Thus, from the evidence of the flesh, we get a proof of the body, and a proof of the flesh from the evidence of the blood. In order, however, that you may discover how anciently wine is used as a figure for blood, turn to Isaiah, who asks, “Who is this that cometh from Edom, from Bosor with garments dyed in red, so glorious in His apparel, in the greatness of his might? Why are thy garments red, and thy raiment as his who cometh from the treading of the full winepress?” The prophetic Spirit contemplates the Lord as if He were already on His way to His passion, clad in His fleshly nature; and as He was to suffer therein, He represents the bleeding condition of His flesh under the metaphor of garments dyed in red, as if reddened in the treading and crushing process of the wine-press, from which the labourers descend reddened with the wine-juice, like men stained in blood. Much more clearly still does the book of Genesis foretell this, when (in the blessing of Judah, out of whose tribe Christ was to come according to the flesh) it even then delineated Christ in the person of that patriarch, saying, “He washed His garments in wine, and His clothes in the blood of grapes” —in His garments and clothes the prophecy pointed out his flesh, and His blood in the wine. Thus did He now consecrate His blood in wine, who then (by the patriarch) used the figure of wine to describe His blood.

No one need take my word alone on this. Protestant patristic scholar J. N. D. Kelly believes the same thing about Tertullian, over against Calvin’s understanding:

In the third century the early Christian identification of the eucharistic bread and wine with the Lord’s body and blood continued unchanged, although a difference of approach can be detected in East and West. The outline, too, of a more considered theology of the eucharistic sacrifice begins to appear.

In the West the equation of the consecrated elements with the body and blood was quite straightforward, although the fact that the presence is sacramental was never forgotten. Hippolytus speaks of ‘the body and the blood’ through which the Church is saved, and Tertullian regularly describes [E.g. de orat. 19; de idol. 7] the bread as ‘the Lord’s body.’ The converted pagan, he remarks [De pud. 9], ‘feeds on the richness of the Lord’s body, that is, on the eucharist.’ The realism of his theology comes to light in the argument [De res. carn. 8], based on the intimate relation of body and soul, that just as in baptism the body is washed with water so that the soul may be cleansed, so in the eucharist ‘the flesh feeds on Christ’s body and blood so that the soul may be filled with God.’ Clearly his assumption is that the Savior’s body and blood are as real as the baptismal water.” (Early Christian Doctrines, Harper SanFrancisco, 1978, 211)

Kelly goes on to analyze the exact question and passage at hand here: what Tertullian means by “figure”:

Occasionally these writers use language which has been held to imply that, for all its realist sound, their use of the terms ‘body’ and ‘blood’ may after all be merely symbolical. Tertullian, for example, refers [E.g. C. Marc. 3,19; 4,40] to the bread as ‘a figure’ (figura) of Christ’s body, and once speaks [Ibid I,14: cf. Hippolytus, apost. trad. 32,3] of ‘the bread by which He represents (repraesentat) His very body.’ Yet we should be cautious about interpreting such expressions in a modern fashion. According to ancient modes of thought a mysterious relationship existed between the thing symbolized and its symbol, figure or type; the symbol in some sense was the thing symbolized. Again, the verb repraesentare, in Tertullian’s vocabulary [Cf. ibid 4,22; de monog. 10], retained its original significance of ‘to make present.’ All that his language really suggests is that, while accepting the equation of the elements with the body and blood, he remains conscious of the sacramental distinction between them. In fact, he is trying, with the aid of the concept of figura, to rationalize to himself the apparent contradiction between (a) the dogma that the elements are now Christ’s body and blood, and (b) the empirical fact that for sensation they remain bread and wine. (Kelly, ibid., 212)

And certainly Christ said of his glorified body, “Handle me, and see; for a spirit hath not flesh and bones, as ye see me have” (Luke 24:39). Here, by the lips of Christ himself, the reality of his flesh is proved, by its admitting of being seen and handled.

Exactly; and His “glorified” Body (note that this is before the Ascension, not after) already had extraordinary qualities that show there was far more in play than ordinariness. He was able to go through walls, even though He was not a spirit (Lk 24:39 above):

John 20:19 On the evening of that day, the first day of the week, the doors being shut where the disciples were, for fear of the Jews, Jesus came and stood among them and said to them, “Peace be with you.”

John 20:26 Eight days later, his disciples were again in the house, and Thomas was with them. The doors were shut, but Jesus came and stood among them, and said, “Peace be with you.”

Disciples were “startled and frightened” by Him (Lk 24:36) and didn’t recognize Him (Lk 24:15-16, 30-31; Jn 20:14-16). If all these unusual things were true of Him then, why is the Real, Substantial Presence in the Eucharist and transubstantiation frowned upon as impossible miracles? Are they any more impossible for God than rising from the dead itself?

Take these away, and it will cease to be flesh.

Only in a completely “natural” understanding. But glorified bodies are already in the realm of the supernatural, so Calvin is beating a dead horse. He is stuck in the natural world, whereas this is a supernatural matter.

They always betake themselves to their lurking-place of dispensation, which they have fabricated.

We haven’t fabricated anything: it all flows from Holy Scripture and solid reasoning and a robust faith in what God can and does do.

But it is our duty so to embrace what Christ absolutely declares, as to give it an unreserved assent.

Amen! Finally, something I can wholeheartedly agree with!

He proves that he is not a phantom, because he is visible in his flesh. Take away what he claims as proper to the nature of his body, and must not a new definition of body be devised?

A glorified body is already a new definition. A God-Man is already a new and indeed completely unique thing; so is a body that can rise from the dead and ascend to heaven.

Then, however they may turn themselves about, they will not find any place for their fictitious dispensation in that passage, in which Paul says, that “our conversation is in heaven; from whence we look for the Saviour, the Lord Jesus Christ: who shall change our vile body, that it may be fashioned like unto his glorious body” (Phil. 3:20, 21).

Yes: the glorified Jesus comes from heaven at the Second Coming. That doesn’t rule out the Eucharist.

We are not to hope for conformity to Christ in these qualities which they ascribe to him as a body, without bounds, and invisible.

He is omnipresent in His Divine Nature.

They will not find any one so stupid as to be persuaded of this great absurdity.

Only all the Church fathers . . .

Let them not, therefore, set it down as one of the properties of Christ’s glorious body, that it is, at the same time, in many places, and in no place.

No one is saying that it is “in no place,” so that is a red herring. It can be in many places, by virtue of God’s omnipotence.

In short, let them either openly deny the resurrection of his flesh, or admit that Christ, when invested with celestial glory, did not lay aside his flesh, but is to make us, in our flesh, his associates, and partakers of the same glory, since we are to have a common resurrection with him. For what does Scripture throughout deliver more clearly than that, as Christ assumed our flesh when he was born of the Virgin, and suffered in our true flesh when he made satisfaction for us, so on rising again he resumed the same true flesh, and carried it with him to heaven?

It was the same flesh, but was glorified, just as we will be one day, too.

The hope of our resurrection, and ascension to heaven, is, that Christ rose again and ascended, and, as Tertullian says (De Resurrect. Carnis), “Carried an earnest of our resurrection along with him into heaven.”

Absolutely.

Moreover, how weak and fragile would this hope be, had not this very flesh of ours in Christ been truly raised up, and entered into the kingdom of heaven. But the essential properties of a body are to be confined by space, to have dimension and form.

Jesus transcended dimension when He walked through walls. He will transcend space at His second coming, when every eye shall see Him (Matt 24:30).

Have done, then, with that foolish fiction, which affixes the minds of men, as well as Christ, to bread. For to what end this occult presence under the bread, save that those who wish to have Christ conjoined with them may stop short at the symbol?

It is the extension of the incarnation and a means to become all the closer to Christ, and to be saved, as He said.

But our Lord himself wished us to withdraw not only our eyes, but all our senses, from the earth, forbidding the woman to touch him until he had ascended to the Father (John 20:17). When he sees Mary, with pious reverential zeal, hastening to kiss his feet, there could be no reason for his disapproving and forbidding her to touch him before he had ascended to heaven, unless he wished to be sought nowhere else.

That is certainly not the only possible interpretation.

The objection, that he afterwards appeared to Stephen, is easily answered. It was not necessary for our Saviour to change his place, as he could give the eyes of his servant a power of vision which could penetrate to heaven.

He can do that but for some inexplicable reason He can’t appear in the Holy Eucharist? Calvin’s argument gets weirder by the minute.

The same account is to be given of the case of Paul. The objection, that Christ came forth from the closed sepulchre, and came in to his disciples while the doors were shut (Mt. 28:6; John 20:19), gives no better support to their error.

Really?

For as the water, just as if it had been a solid pavement, furnished a path to our Saviour when he walked on it (Mt. 14.),

More strange behavior for a human body . . .

so it is not strange that the hard stone yielded to his step; although it is more probable that the stone was removed at his command, and forthwith, after giving him a passage, returned to its place. To enter while the doors were shut, was not so much to penetrate through solid matter, as to make a passage for himself by divine power, and stand in the midst of his disciples in a most miraculous manner.

What’s the difference? This is textbook sophistry: make a distinction with no logical difference (the mere appearance of strength of argument where there is none in actuality):

Proposition: “enter while the doors were shut”.

Description #1: “not so much to penetrate through solid matter”.

Description #2: “make a passage for himself by divine power . . . in a most miraculous manner.”

Calvin approves of the positive assertion #2 and sophistically contends that it is different from the negative claim of #1, that he objects to. But how are the two essentially different? Calvin has been arguing all along that Jesus is somehow limited by the laws of nature and matter. But He had a body when He walked through walls.

They gain nothing by quoting the passage from Luke, in which it is said, that Christ suddenly vanished from the eyes of the disciples, with whom he had journed to Emmaus (Luke 24:31). In withdrawing from their sight, he did not become invisible: he only disappeared.

Another distinction without a difference; this, too, was a physical Christ, after the resurrection. Calvin is special pleading all over the place. It is embarrassing how weak and insubstantial (no pun intended) and pathetic; how desperate, his arguments are. Most of them in this regard are not even worthy of the name of “argument.”

Thus Luke declares that, on the journeying with them, he did not assume a new form, but that “their eyes were holden.” But these men not only transform Christ that he may live on the earth, but pretend that there is another elsewhere of a different description. In short, by thus trifling, they, not in direct terms indeed, but by a circumlocution, make a spirit of the flesh of Christ; and, not contented with this, give him properties altogether opposite. Hence it necessarily follows that he must be twofold.

Jesus is omnipotent. God the Father is omnipotent. That is all that is strictly necessary for the Eucharist to be possible. The indication that it is in fact a reality is in Scripture. The plausibility of this state of affairs is indicated by the dozens of biblical analogies I have been producing. The implausibility of the contrary (Calvin’s position) is shown in the logical and scriptural counter-indications to them at every turn.

*

This makes the many scriptural references (I found eleven) to Christ “in” us or among us or “all in all” also absurd. If Calvin wants to attack the Bible, so be it. But it is the Bible he is differing with, not some novel Catholic interpretation of the Bible. He is the innovator, not us.

it will still be necessary to prove the immensity, without which it is vain to attempt to include Christ under the bread. Unless the body of Christ can be everywhere without any boundaries of space, it is impossible to believe that he is hid in the Supper under the bread.

The Catholic position doesn’t entail a “bodily omnipresence”; only a local presence in many places. Calvin continues to provide no solid grounds of refutation.

Hence, they have been under the necessity of introducing the monstrous dogma of ubiquity.

Ubiquity itself is a Lutheran error, and not a Catholic doctrine (as noted in past installments). It holds that Jesus is omnipresent even in His Human Nature.

But it has been demonstrated by strong and clear passages of Scripture, first, that it is bounded by the dimensions of the human body; and, secondly, that its ascension into heaven made it plain that it is not in all places, but on passing to a new one, leaves the one formerly occupied.

These arbitrary limitations of an omnipotent God have all been dealt with many times now in this reply to Book IV of The Institutes and refuted in many different ways, in my opinion. Calvin repeats the same old weak arguments over and over. I need not repeat myself ad nauseam, too.

The promise to which they appeal, “I am with you always, even to the end of the world,” is not to be applied to the body.

Correct, but Calvin also asked where there was one syllable in the Bible about an invisible presence of Jesus, and this is one.

First, then, a perpetual connection with Christ could not exist, unless he dwells in us corporeally, independently of the use of the Supper;

How does that follow? This is more of Calvin’s odd reasoning.

and, therefore, they have no good ground for disputing so bitterly concerning the words of Christ, in order to include him under the bread in the Supper. Secondly, the context proves that Christ is not speaking at all of his flesh, but promising the disciples his invincible aid to guard and sustain them against all the assaults of Satan and the world.

I don’t see how that passage excludes any eucharistic sense whatever. It might very well include that as well as the non-material indwelling.

For, in appointing them to a difficult office, he confirms them by the assurance of his presence, that they might neither hesitate to undertake it, nor be timorous in the discharge of it; as if he had said, that his invincible protection would not fail them. Unless we would throw everything into confusion, must it not be necessary to distinguish the mode of presence?

No.

And, indeed, some, to their great disgrace, choose rather to betray their ignorance than give up one iota of their error. I speak not of Papists, whose doctrine is more tolerable, or at least more modest;

About as close to a compliment that Calvin ever gives to Catholics . . .

but some are so hurried away by contention as to say, that on account of the union of natures in Christ, wherever his divinity is, there his flesh, which cannot be separated from it, is also; as if that union formed a kind of medium of the two natures, making him to be neither God nor man. So held Eutyches, and after him Servetus. But it is clearly gathered from Scripture that the one person of Christ is composed of two natures, but so that each has its peculiar properties unimpaired. That Eutyches was justly condemned, they will not have the hardihood to deny. It is strange that they attend not to the cause of condemnation—viz. that destroying the distinction between the natures, and insisting only on the unity of person, he converted God into man and man into God. What madness, then, is it to confound heaven with earth, sooner than not withdraw the body of Christ from its heavenly sanctuary?

What madness is it to confine Jesus to heaven? Where is that ever stated in Scripture?

In regard to the passages which they adduce, “No man has ascended up to heaven, but he that came down from heaven, even the Son of man which is in heaven” (John 3:13); “The only-begotten Son, who is in the bosom of the Father, he hath declared him” (John 1:18), they betray the same stupidity, scouting the communion of properties (idiomatum, κοινωνίαν), which not without reason was formerly invented by holy Fathers. Certainly when Paul says of the princes of this world that they “crucified the Lord of glory” (1 Cor. 2:8), he means not that he suffered anything in his divinity, but that Christ, who was rejected and despised, and suffered in the flesh, was likewise God and the Lord of glory. In this way, both the Son of man was in heaven because he was also Christ; and he who, according to the flesh, dwelt as the Son of man on earth, was also God in heaven. For this reason, he is said to have descended from heaven in respect of his divinity, not that his divinity quitted heaven to conceal itself in the prison of the body, but because, although he filled all things, it yet resided in the humanity of Christ corporeally, that is, naturally, and in an ineffable manner. There is a trite distinction in the schools which I hesitate not to quote. Although the whole Christ is everywhere, yet everything which is in him is not everywhere.

This section, that contradicts other aspects of Calvin’s argument, was dealt with above.

I wish the Schoolmen had duly weighed the force of this sentence, as it would have obviated their absurd fiction of the corporeal presence of Christ.

What Jesus teaches; what the apostles and fathers and Schoolmen and Doctors of the Church taught, is not an absurd fiction. Calvin’s denial on arbitrary and unreasonable grounds is that.

Therefore, while our whole Mediator is everywhere, he is always present with his people, and in the Supper exhibits his presence in a special manner; yet so, that while he is wholly present, not everything which is in him is present, because, as has been said, in his flesh he will remain in heaven till he come to judgment.

More as-yet-unestablished and unfounded conclusions . . .

(originally 12-1-09)

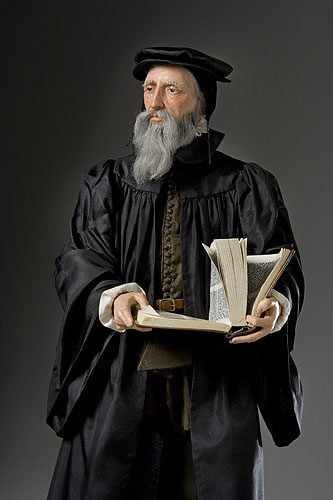

Photo credit: Historical mixed media figure of John Calvin produced by artist/historian George S. Stuart and photographed by Peter d’Aprix: from the George S. Stuart Gallery of Historical Figures archive [Wikimedia Commons / Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license]

***