[See also Part II]

Introduction

In an e-mail, I wrote (more or less “off the cuff”):

As for my $00.02 on this, I think the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki was clearly immoral by just war standards, and cannot be morally justified. Pre-emption is a notion I have no trouble with, and I believe it can be synthesized with traditional just war standards, but killing 100,000 civilians, whether at Dresden or in Japan, cannot.

The decision may have been “complex” or “understandable” at the time, but with the benefit of hindsight we would fully expect to have a more informed, objective opinion on it 60 years later, than we did in the frenzy and passion of (justified) war.

In a second informal response to a friend, responding more directly to replies, I stated:

With all due respect, I think what you provided in that last letter doesn’t even come close to justifying it or overcoming the weight of the Catholic just war criteria. I think it is a slam dunk. One can never deliberately do evil in order to prevent further evil. One must always use just means. I can understand “unintended consequences” and so forth, but when you are deliberately dropping a bomb like these were, you know what is going to happen, and many thousands of women and children who had nothing directly to do with the Japanese war effort were slaughtered. This is immoral and unjustifiable. Period. I think it is even in natural law, before you even get to Catholic moral theology, developed over 20 centuries.

Is this blunt? Sure, as usually in my writings, for better or ill. I’m a straight shooter, and always will be. Overstated or “undiplomatic” or insufficiently nuanced and qualified? Perhaps; indeed quite possibly. All sides at least agree that it is tragic.

I do not suggest in the least that anyone who disagrees with my own position on this matter (whatever it is, or turns out to be) is any less of a good or orthodox or moral Catholic, or any less concerned with the seriousness of the ethical question and the larger question of just war and the tragic necessity of war at times, or some kind of simplistic, sheeplike, unthinking fool.

Many prominent Catholics, and many in the apologetics movement (of which I am a part) oppose the bombings as immoral and unjustifiable. For what it’s worth (I’m not appealing to the ad populum fallacy; simply stating what I believe to be a fact), the pro-bombing position is a minority view among orthodox Catholics. That doesn’t make it automatically wrong; it has to be discussed on its merits or demerits. I’m no expert on this, which is why I will be citing many others who are much more so, and better placed to authoritatively comment on this issue.

The Horrors of World War II and the Dangers of the Benefit of Hindsight

Dr. Art Sippo, a Catholic apologist, and friend of mine, wrote (and I completely agree with what he states):

In some cases more than one moral option may present itself so that there is no one “right” or “wrong” answer. The most despicable people imaginable are those who vilify the man who made a choice in good faith under fire. It is one thing to say that they disagreed with his choice but another thing entirely to say that he was a bad person for choosing what he chose. That is not necessarily so. Sometimes a man can only do his best and hope that later generations will appreciate how hard his decision was.

. . . Truman made a choice based on the cards he was dealt and he did what he thought was right. In light of the horrors of this terrible war, I can not blame him for trying to end it swiftly and decisively by making the aggressors who started it bear the brunt of the final assault.

Likewise, George Weigel describes some horrific details of Japanese resolve [link now defunct], citing William Manchester’s book, Goodbye, Darkness:

“After the great banzai obliterated their army, depriving them of their protectors, they decided that they, too, must die. Most of them gathered on two heights now called Banzai Cliff, an eighty-foot bluff overlooking the water, and, just inland from there. Suicide Cliff, which soars one thousand feet above clumps of jagged rocks.

“… Saito [the Japanese commander] had left a last message to his civilian countrymen, too: “As it says in the Senjinkum [Ethics], ‘I will never suffer the disgrace of being taken alive,’ and I will offer up the courage of my soul and calmly rejoice in living by the eternal principle.” In a final, cruel twist of the knife he reminded mothers of the oyaku-shinju (the parents-children death pact). Mothers, fathers, daughters, sons— all had to die. Therefore children were encouraged to form circles and toss live grenades from hand to hand until they exploded. Their parents dashed babies’ brains out on limestone slabs and then, clutching the tiny corpses, shouted “Tenno! Haiki! Banzai!” (Long live the Emperor!) as they jumped off the brinks of the cliffs and soared downward. Below Banzai Cliff U.S. destroyers trying to rescue those who had survived the plunge found they could not steer among so many bodies; human flesh was jamming their screws. .. . But Suicide Cliff was worse. A brief strip of jerky newsreel footage, preserved in an island museum, shows a distraught mother, her baby in her arms, darting back and forth along the edge of the precipice, trying to make up her mind. Finally she leaps, she and her child joining the ghastly carnage below. There were no survivors at the base of Suicide Cliff.

. . . These deliberately sanguinary tactics help explain the carnage that ensued in February 1945 on Iwo Jima, an island only 5 miles by 2.5 miles in size. There, out of a Japanese garrison of 20,000, only 200 were captured alive, at the cost of 6,000 American deaths and 25,000 wounded Marines. Then there was the invasion of Okinawa in April 1945, the last stepping-stone before the Japanese home islands: 100,000 Japanese soldiers died there, as did 150,000 Okinawan civilians, while the U.S. Marines and Army suffered 75,000 casualties before the island was secured in mid-June.

Was Use of the A-Bomb Understood as Indiscriminate Killing to More or Less Extent?

Dr. Art Sippo appears to at least partially affirm this (emphasis added):

No one anticipated that there would be radiation casualties. It was thought that anyone close enough to be radiated would be killed outright by the physical effects of the blast. Had we known this beforehand, would we have used the bombs? I suspect that we would have. We might have modified the target selection or the altitude from which the bombs were dropped . . .

Sippo also admits:

I think that we should not have fire-bombed Dresden or Tokyo as we did.

In my opinion, much of the present argument will hinge upon the necessity for the proponents to prove that there is a crucial moral / tactical distinction between Hiroshima and Nagasaki vs. Dresden and Tokyo, which even many of the proponents of the former acts condemn, along with those of us who decry all four instances as objectively immoral and inconsistent with time-honored Catholic moral-ethical principles.

Catholics Who Oppose the Bombings as Immoral

Karl Keating, in his e-letter of 3 August 2004 [link now defunct], writes:

Many justify the bombings of Nagasaki and Hiroshima by saying the abrupt end to the war saved as many as a million American lives that would have been lost had Japan been invaded. I don’t know where the figure of one million came from. My understanding is that the War Department estimated a maximum of 46,000 casualties in an invasion. That was a worst-case scenario, meaning the likely number of casualties would have been far lower.

Some commentators have argued that no invasion was needed at all, since Japan no longer had an air force or navy and had no domestic source of oil for its industries. A blockade would have resulted in the Japanese war machine and economy grinding to a halt. The war thus could have ended without an invasion, though the end probably would have come long after the summer of 1945.

Be that as it may, what concerns me is the attitude, so prevalent among political conservatives (most of whom are religious conservatives), that there are no limits in defensive warfare: If the other guys started the fight, they deserve whatever they get. In a defensive war it is not a matter of “My country right or wrong” but of “My country can do no wrong,” which is an odd thing coming from conservatives who, on domestic matters, can be highly critical of their government’s moral failings (as regards abortion or homosexuality, say).

To achieve a good, you may not perform a sin. To provide your family financial security, you may not rob a bank. To protect your wife’s health, you may not abort the child she is carrying. And to defeat an enemy in war, you may not violate just war principles. But we did–and more than once, sad to say.

The atomic bombings of Nagasaki and Hiroshima, like the fire bombings of Dresden and other German cities, cannot be squared with Catholic moral principles because the bombings deliberately targeted non-combatants. The evil done by our enemies did not exonerate us from the moral law. Their evils did not provide us justification for evils of our own. Being a Christian in peacetime is difficult; it is more difficult, but even more necessary, in wartime.

Fat Man exploded directly above the Catholic cathedral in Nagasaki. The city was the historical center of Catholicism in Japan and contained about a tenth of the entire Catholic population. The cathedral was filled with worshipers who had gathered to pray for a speedy and just end to the war. It is said their prayers included a petition to offer themselves, if God so willed it, in reparation for the evils perpetrated by their country.

The Catholic Answer Guide, Just War Doctrine [link now defunct] (presumably agreeable to Karl Keating), expands this reasoning a bit:

The treatment of non-hostile individuals in wartime is not the only consideration involved in the just prosecution of a war. The existence of weapons of mass destruction poses special moral challenges. In this regard the Catechism states:

Every act of war directed to the indiscriminate destruction of whole cities or vast areas with their inhabitants is a crime against God and man, which merits firm and unequivocal condemnation. A danger of modern warfare is that it provides the opportunity to those who possess modern scientific weapons – especially atomic, biological, or chemical weapons – to commit such crimes (CCC 2314).

The U.S. has not always been committed to this principle. In the Civil War, World War I, and World War II the United States violated it. Grave violations during World War II included the firebombing of Dresden and the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. These were not attacks designed to destroy targets of military value while sparing civilian populations. They were deliberate attempts to put pressure on enemy governments by attacking non-combatants. As a result, they were grave violations of God’s law, according to which, “the direct and voluntary killing of an innocent human being is always gravely immoral” (John Paul II, Evangelium Vitae 57).

It is important to recognize what this principle does and does not require. While it does require strenuous efforts to avoid harming innocents, it does not require the result of no innocents being harmed. Such a result is impossible to guarantee. Even with the smartest of smart munitions, it is not possible to ensure that no non-combatants will be harmed in wartime. As tragic as it is, collateral damage to innocents is an inescapable consequence of war. Catholic theology recognizes this. It applies to such situations a well-established principle known as the law of double-effect. According to this law it is permissible to undertake an action which has two effects, one good and one evil, provided that certain conditions are met.

Although these conditions can be formulated in different ways, they may be enumerated as follows: (1) the action itself must not be intrinsically evil; (2) the evil effect must not be an end in itself or a means to accomplishing the good effect (in other words, it must be a foreseen but undesired side-effect of the action); and (3) the evil effect must not outweigh the good effect. If these three conditions are met, the action may be taken in spite of the foreseen damage it will do.

The law of double-effect would not have applied to the cases of Dresden, Hiroshima, and Nagasaki. In these situations though the act (dropping bombs) was not intrinsically evil and though it is arguable that in the long run more lives were saved than lost, the second condition was violated because the death of innocents was used as a means to achieve the good of the war’s end.

Fortunately, despite these past, grave transgressions, the United States is now committed to the principle of sparing innocent life during military actions. It has repeatedly and sincerely expressed its intent to minimize civilian casualties and to serve as a liberator of captive populations in the War on Terrorism. The U.S. is now committed to the principles of the just war.

Catholic apologist Jimmy Akin also agrees:

. . . regardless of what one may think of particular instances in the U.S.’s record (which is not perfect; the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were wrong), it remains the case that the U.S. is (d) a stable nation (not likely to become a “failed state” like Somalia) that (c) has a large number of citizens today who will not tolerate leaders who use such weapons indiscriminately (as at Hiroshima and Nagasaki) and (b) will not pass them to terrorists or (a) proliferate them to unstable states.

Fr. Jim Tucker provides further argumentation along these lines:

Today is not only the feast of Edith Stein, it is also the 60th anniversary of the atom bombing of Nagasaki. We patriotic Americans aren’t supposed to question the morality of what our government did in that war, but we’re going to do it anyway. When the bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, tens of thousands of lives of men, women, and children were snuffed out in a single instant, and over a quarter of a million would eventually die of the effects. For centuries, Catholic morality has taught us that it is intrinsically evil to target a civilian population and to resort to indiscriminate killing and destruction, which is exactly what happened in both the atom bombings.

It’s important for us to consider this and come to terms with it — not because we should feel guilty. We shouldn’t feel guilty about Hiroshima and Nagasaki, any more than today’s Germans should feel guilty about the Holocaust. We didn’t do it, but we are under a moral obligation to form our consciences so that this sort of thing will never happen again. And it’s not just about atom bombs: the moral structure of this issue touches all sorts of other cases that abound in today’s world. Our bedrock principle is this: we may never commit an intrinsically evil act, for whatever reason, however good that reason might be. So, even though it’s good that the war ended quickly after the bombings, and it’s good that our soldiers were spared a bloody invasion of Japan, those good ends can never excuse using immoral means to achieve that end.

Nagasaki is also connected to another of the saints of World War II, St Maximilian Kolbe, a Polish priest killed by the Nazis at Auschwitz. Most people don’t realize that Nagasaki was the one place in Japan that had a strong Christian presence. Nagasaki was one of the chief places that the crucifixions of the Japanese martyrs had taken place centuries before. It was also at Nagasaki that St Maximilian Kolbe went to build one of his “Cities of the Immaculata.” So, when Harry Truman’s atom bomb fell on Nagasaki sixty years ago today, many of the victims burned to ashes and melted away were not just fellow human beings, but fellow Roman Catholics.

Cardinal Alfredo Ottaviani wrote in 1947 [link now defunct]:

The extent of the damage done to national assets by aerial warfare, and the dreadful weapons that have been introduced of late, is so great that it leaves both vanquished and victor the poorer for years after.

Innocent people, too, are liable to great injury from the weapons in current use: hatred is on that account excited above measure; extremely harsh reprisals are provoked; wars result which flaunt every provision of the jus gentium, and are marked by a savagery greater than ever. And what of the period immediately after a war? Does not it also provide an obvious pointer to the enormous and irreparable damage which war, the breeding place of hate and hurt, must do to the morals and manners of nations?

These considerations, and many others which might be adduced besides, show that modern wars can never fulfil those conditions which (as we stated earlier on in this essay) govern – theoretically – a just and lawful war. Moreover, no conceivable cause could ever be sufficient justification for the evils, the slaughter, the destruction, the moral and religious upheavals which war today entails.

[I would argue that current-day technology with non-nuclear precision, “surgical” strikes, smart bombs, etc. make just war conditions far easier to fulfill than 60 years ago (indeed I believe that the criteria are fully met in the Iraqi War); but one cannot anachronistically project today’s weapons back to 1945; the atomic bombings as they were carried out remain unjustifiable by catholic moral standards]

Pat Buchanan (“Hiroshima, Nagasaki & Christian Morality”) notes how the decision to engage in immoral, indiscriminate bombing had already been deliberately, self-consciously adopted in the bombing of Dresden:

But if terrorism is the massacre of innocents to break the will of rulers, were not Hiroshima and Nagasaki terrorism on a colossal scale?

Churchill did not deny what the Allied air war was about. Before departing for Yalta, he ordered Operation Thunderclap, a campaign to “de-house” civilians to clog roads so German soldiers could not move to stop the offensive of the Red Army. British Air Marshal “Bomber” Harris put Dresden, a jewel of a city and haven for hundreds of thousands of terrified refugees, on the target list.

On the first night, 770 Lancasters arrived around 10:00. In two waves, 650,000 incendiary bombs rained down, along with 1,474 tons of high explosives. The next morning, 500 B-17s arrived in two waves, with 300 fighter escorts to strafe fleeing survivors.

Estimates of the dead in the Dresden firestorm range from 35,000 to 250,000. Wrote the Associated Press, “Allied war chiefs have made the long-awaited decision to adopt deliberate terror bombing of German populated centers as a ruthless expedient to hasten Hitler’s doom.”

In a memo to his air chiefs, Churchill revealed what Dresden had been about, “It seems to me that the moment has come when the question of bombing of German cities simply for the sake of increasing the terror, though under other pretexts, should be reviewed.”

Yet, whatever the mindset of Japan’s warlords in August 1945, the moral question remains. In a just war against an evil enemy, is the deliberate slaughter of his women and children in the thousands justified to break his will to fight? Traditionally, the Christian’s answer has been no.

Truman’s defenders argue that the number of U.S. dead in any invasion would have been not 46,000, as one military estimate predicted, but 500,000. Others contend the cities were military targets.

But with Japan naked to our B-29s, her surface navy at the bottom of the Pacific, the home islands blockaded, what was the need to invade at all? On his island-hopping campaign back to the Philippines, MacArthur routinely bypassed Japanese strongholds like Rabaul, cut them off and left them to “rot on the vine.”

And if Truman considered Hiroshima and Nagasaki military targets, why, in the Cabinet meeting of Aug. 10, as historian Ralph Raico relates, did he explain his reluctance to drop a third bomb thus: “The thought of wiping out another 100,000 people was too horrible,” he said. He didn’t like the idea of killing “all those kids.”

Of Truman’s decision, his own chief of staff, Adm. William Leahy, wrote: “This use of this barbarous weapon at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against Japan. My own feeling was that in being the first to use it, we had adopted an ethical standard common to the barbarians of the Dark Ages. I was not taught to make wars in that fashion …”

Maclin Horton emphasizes the ethical absolute, which remains valid, even within a concrete situation of extreme complexity:

We must face, and take responsibility for, the simple fact that what we did at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was wrong. I call this a “simple” fact fully aware that not everyone grants its status as fact, much less that it is simple. The simplicity to which I refer is not that of the historical decision, which was indeed complex, but of the abstract ethical principle: it is wrong to target noncombatants in war. It is wrong to incinerate non-combatants in their hundreds of thousands at a swoop. It is wrong, and, what perhaps most needs saying in our present ethical climate, even if you have powerful reasons for doing it, it is still wrong. And if it is not wrong, then our argument with, say, Osama bin-Laden becomes a question of who struck first and who had the greater provocation; that is, we have no principled argument against his methods.

I am not saying that the circumstances surrounding the decision to use the atomic bomb were such that the right decision should have been easy.

George Weigel readily concedes the objective immorality of the bombings, and their clash with just war theory, while noting the limitations of the options of that terrible time (as opposed to maintaining that the actions were just because of the complexities of the ethics and military strategy):

In these circumstances, which were the real world circumstances of the time, the use of atomic weapons seems far less a deliberate atrocity than a tragic necessity.

This is not to suggest that the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki was, or is, easily justifiable under the moral criteria of the classic just war tradition. But the moral barrier had been breached long before August 6 and August 8, 1945. So-called strategic bombing, aimed at the destruction of civilian populations, had been going on for five years; none of it met the just war in bello criteria of proportionality and discrimination. Indeed, if one measures the violation of non-combatant immunity statistically, the fire-bombing of Tokyo, Osaka, Kobe, Nagoya, and other Japanese cities was a greater breach of the just war tradition than Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

That the Germans had destroyed Rotterdam, the British, Hamburg, and the British and Americans, Dresden, does not “justify” the American destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. But certain moral distinctions can and should be drawn between the bombing of cities for purposes of sheer terror (Rotterdam) or revenge (Dresden), and the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which, on the best available evidence, was undertaken with a legitimate strategic purpose in mind. That purpose was summarized succinctly by Truman biographer David McCullough: “If you want one explanation as to why Truman dropped the bomb: ‘Okinawa.’ It was done to stop the killing.”

The greater legitimacy of an end does not, of course, justify any possible means. But recognizing the legitimacy of the end does enable us to enter imaginatively and even sympathetically into the moral struggle over means faced by a responsible political leader confronting a brace of bad choices.

It sometimes happens, these days, that a parallel is drawn between Auschwitz and Hiroshima, as two embodiments of the evil of the Second World War. But this seems wrong. What Harry Truman did in August 1945 was, strictly speaking, unjustifiable in classic moral terms. But it was understandable, and it was forgivable. What was done at Auschwitz was unjustifiable, maniacal, and, in this world’s terms, unforgivable. That is a considerable moral difference.

At my parish church on the morning of August 6, 1995, we prayed God to grant “that no nuclear weapons will ever again be used.” It was a petition to which all could respond with a heartfelt, “Lord, hear our prayer.” Only by facing squarely the unavoidable moral dilemma confronted by President Truman will we gain a measure of the wisdom that might help us avoid similar dilemmas in the future. By reducing the decision to use atomic weapons at Hiroshima and Nagasaki to crudely political, even ideological, categories, the revisionists do a disservice not only to history but to the future, and to the cause of peace.

United States Conference of Catholic Bishops: Statement of 6 August 2004 [link now defunct]:

World War II, which liberated many and defeated tyranny but which left as a shameful legacy instances of combat, was conducted without distinction between civilian and soldier. In the decades since the bombing, some have advanced the argument that despite the horrendous magnitude of civilian suffering, these actions can be justified by the efficient end of combat it affected. But secular ethicists and moral theologians alike echo the words of the Second Vatican Council: ‘Every act of war directed to the indiscriminate destruction of whole cities or vast areas with their inhabitants is a crime against God and man, which merits firm and unequivocal condemnation.’ The Church has a long tradition of condemning acts of war that bring ‘widespread, unspeakable suffering and destruction.’ At a time when much of the world is gripped by fear of terrorism and a few voices hint that the time may again come when the U.S. should call upon its nuclear arsenal to make “quick work” of frightening threats, it is fitting to reassert our commitment to disarmament and the conduct of limited war only as a last resort.

What Actually Happened at Hiroshima and Nagasaki? Who Died, and Who Was “Targeted”?

Ralph Raico, a scholar at the Ludwig von Mises Institute, provides some much-needed factual information:

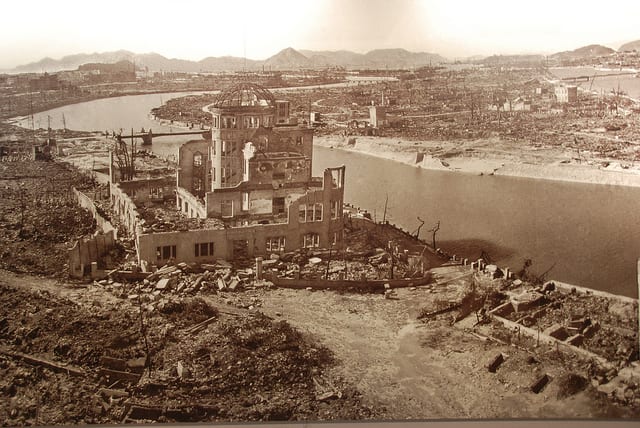

Probably around two hundred thousand persons were killed in the attacks and through radiation poisoning; the vast majority were civilians, including several thousand Korean workers. Twelve U.S. Navy fliers incarcerated in a Hiroshima jail were also among the dead.

On August 9, 1945, he [Truman] stated: “The world will note that the first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, a military base. That was because we wished in this first attack to avoid, insofar as possible, the killing of civilians.”

This, however, is absurd. Pearl Harbor was a military base. Hiroshima was a city, inhabited by some three hundred thousand people, which contained military elements. In any case, since the harbor was mined and the U.S. Navy and Air Force were in control of the waters around Japan, whatever troops were stationed in Hiroshima had been effectively neutralized.

On other occasions, Truman claimed that Hiroshima was bombed because it was an industrial center. But, as noted in the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey, “all major factories in Hiroshima were on the periphery of the city – and escaped serious damage.” The target was the center of the city.

Moreover, the notion that Hiroshima was a major military or industrial center is implausible on the face of it. The city had remained untouched through years of devastating air attacks on the Japanese home islands, and never figured in Bomber Command’s list of the 33 primary targets.

Thus, the rationale for the atomic bombings has come to rest on a single colossal fabrication, which has gained surprising currency: that they were necessary in order to save a half-million or more American lives. These, supposedly, are the lives that would have been lost in the planned invasion of Kyushu in December, then in the all-out invasion of Honshu the next year, if that was needed. But the worst-case scenario for a full-scale invasion of the Japanese home islands was forty-six thousand American lives lost. The ridiculously inflated figure of a half-million for the potential death toll – nearly twice the total of U.S. dead in all theaters in the Second World War- is now routinely repeated in high-school and college textbooks and bandied about by ignorant commentators.

Those who may still be troubled by such a grisly exercise in cost-benefit analysis – innocent Japanese lives balanced against the lives of Allied servicemen – might reflect on the judgment of the Catholic philosopher G.E.M. Anscombe, who insisted on the supremacy of moral rules. When, in June 1956, Truman was awarded an honorary degree by her university, Oxford, Anscombe protested. Truman was a war criminal, she contended, for what is the difference between the U.S. government massacring civilians from the air, as at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the Nazis wiping out the inhabitants of some Czech or Polish village?

Anscombe’s point is worth following up. Suppose that, when we invaded Germany in early 1945, our leaders had believed that executing all the inhabitants of Aachen, or Trier, or some other Rhineland city would finally break the will of the Germans and lead them to surrender. In this way, the war might have ended quickly, saving the lives of many Allied soldiers. Would that then have justified shooting tens of thousands of German civilians, including women and children? Yet how is that different from the atomic bombings?

By early summer 1945, the Japanese fully realized that they were beaten. Why did they nonetheless fight on? As Anscombe wrote: “It was the insistence on nconditional surrender that was the root of all evil.”

. . . as Major General J.F.C. Fuller, one of the century’s great military historians, wrote in connection with the atomic bombings:

“Though to save life is laudable, it in no way justifies the employment of means which run counter to every precept of humanity and the customs of war. Should it do so, then, on the pretext of shortening a war and of saving lives, every imaginable atrocity can be justified.”

While the mass media parroted the government line in praising the atomic incinerations, prominent conservatives denounced them as unspeakable war crimes. Felix Morley, constitutional scholar and one of the founders of Human Events, drew attention to the horror of Hiroshima, including the “thousands of children trapped in the thirty-three schools that were destroyed.” He called on his compatriots to atone for what had been done in their name, and proposed that groups of Americans be sent to Hiroshima, as Germans were sent to witness what had been done in the Nazi camps. The Paulist priest, Father James Gillis, editor of The Catholic World and another stalwart of the Old Right, castigated the bombings as “the most powerful blow ever delivered against Christian civilization and the moral law.” David Lawrence, conservative owner of U.S. News and World Report, continued to denounce them for years. The distinguished conservative philosopher Richard Weaver was revolted by “the spectacle of young boys fresh out of Kansas and Texas turning nonmilitary Dresden into a holocaust . . . pulverizing ancient shrines like Monte Cassino and Nuremberg, and bringing atomic annihilation to Hiroshima and Nagasaki.”

Weaver considered such atrocities as deeply “inimical to the foundations on which civilization is built.”

Today, self-styled conservatives slander as “anti-American” anyone who is in the least troubled by Truman’s massacre of so many tens of thousands of Japanese innocents from the air. This shows as well as anything the difference between today’s “conservatives” and those who once deserved the name.

Leo Szilard was the world-renowned physicist who drafted the original letter to Roosevelt that Einstein signed, instigating the Manhattan Project. In 1960, shortly before his death, Szilard stated another obvious truth:

“If the Germans had dropped atomic bombs on cities instead of us, we would have defined the dropping of atomic bombs on cities as a war crime, and we would have sentenced the Germans who were guilty of this crime to death at Nuremberg and hanged them.”

Lowell Ponte, after chronicling the Christian history of Nagasaki, describes the grim reality of the bombing:

The plutonium bomb called “Fat Man” dropped from the B-29’s bomb bay at 11:02 A.M. . . .

The man-made sun, brighter than a million Rising Sun Japanese flags, ignited about 1,600 feet above Ground Zero. Its wind shockwave moving at 1,400 miles per hour pulverized the crowded homes below like a giant fist. Its energy flash burned flesh from bone, then vaporized both before a scream could reach melting human lips.

Scarcely a fifth of a mile from Ground Zero, the Urakami Cathedral, its lovingly-crafted stained glass, and the worshippers inside were smashed into dust and goo and flash-broiled. Heavy carved statues of Jesus and Mary were scorched black in an instant.

The bomb, bigger than Hiroshima’s, with the explosive force of 21,000 tons of TNT, destroyed essentially everything and everyone within 1.2 miles of Ground Zero. Thousands of close-clustered wooden homes and their residents vanished in the glow of a rising mushroom cloud.

In that moment, an estimated 73,884 people died – at least one in 10 of them Christians. Another 75,000 were blinded, had skin burned off, or were injured by the blast or engulfing firestorms or collapsing buildings for miles around. Thousands more would die from radiation or injury over days or months.

As one writer about the Cathedral put it, through this atom bomb blast the Truman Administration was “ironically killing more Christians than had ever been killed in Japan during centuries of persecution.”

Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin, Co-chairs of the Historians’ Committee for Open Debate on Hiroshima, wrote to the Smithsonian Institute concerning the Enola Gay Exhibit, in 1995:

Unfortunately, the Enola Gay exhibit contains a text which goes far beyond the facts. The critical label at the heart of the exhibit makes the following assertions:

* The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki “destroyed much of the two cities and caused many tens of thousands of deaths.” This substantially understates the widely accepted figure that at least 200,000 men, women and children were killed at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. (Official Japanese records calculate a figure of more than 200,000 deaths – the vast majority of victims being women, children and elderly men.)

* “However,” claims the Smithsonian, “the use of the bombs led to the immediate surrender of Japan and made unnecessary the planned invasion of the Japanese home islands.” Presented as fact, this sentence is actually a highly contentious interpretation. For example, an April 30, 1946 study by the War Department’s Military Intelligence Division concluded, “The war would almost certainly have terminated when Russia entered the war against Japan.” (The Soviet entry into the war on August 8th is not even mentioned in the exhibit as a major factor in the Japanese surrender.) And it is also a fact that even after Hiroshima and Nagasaki were destroyed, the Japanese still insisted that Emperor Hirohito be allowed to remain emperor as a condition of surrender. Only when that assurance was given did the Japanese agree to surrender. This was precisely the clarification of surrender terms that many of Truman’s own top advisors had urged on him in the months prior to Hiroshima. This, too, is a widely known fact.

* The Smithsonian’s label also takes the highly partisan view that, “It was thought highly unlikely that Japan, while in a very weakened military condition, would have surrendered unconditionally without such an invasion.” Nowhere in the exhibit is this interpretation balanced by other views. Visitors to the exhibit will not learn that many U.S. leaders–including Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, Admiral William D. Leahy, War Secretary Henry L. Stimson, Acting Secretary of State Joseph C. Grew and Assistant Secretary of War John J. McCloy – thought it highly probable that the Japanese would surrender well before the earliest possible invasion, scheduled for November 1945. It is spurious to assert as fact that obliterating Hiroshima in August was needed to obviate an invasion in November. This is interpretation–the very thing you said would be banned from the exhibit.

* In yet another label, the Smithsonian asserts as fact that “Special leaflets were then dropped on Japanese cities three days before a bombing raid to warn civilians to evacuate.” The very next sentence refers to the bombing of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, implying that the civilian inhabitants of Hiroshima were given a warning. In fact, no evidence has ever been uncovered that leaflets warning of atomic attack were dropped on Hiroshima. Indeed, the decision of the Interim Committee was “that we could not give the Japanese any warning.”

* In a 16 minute video film in which the crew of the Enola Gay are allowed to speak at length about why they believe the atomic bombings were justified, pilot Col. Paul Tibbits asserts that Hiroshima was “definitely a military objective.” Nowhere in the exhibit is this false assertion balanced by contrary information. Hiroshima was chosen as a target precisely because it had been very low on the previous spring’s campaign of conventional bombing, and therefore was a pristine target on which to measure the destructive powers of the atomic bomb. Defining Hiroshima as a “military” target is analogous to calling San Francisco a “military” target because it has a port and contains the Presidio. James Conant, a member of the Interim Committee that advised President Truman, defined the target for the bomb as a “vital war plant employing a large number of workers and closely surrounded by workers’ houses.” There were indeed military factories in Hiroshima, but they lay on the outskirts of the city. Nevertheless, the Enola Gay bombardier’s instructions were to target the bomb on the center of this civilian city.

The few words in the exhibit that attempt to provide some historical context for viewing the Enola Gay amount to a highly unbalanced and one-sided presentation of a largely discredited post-war justification of the atomic bombings.

Such errors of fact and such tendentious interpretation in the exhibit are no doubt partly the result of your decision earlier this year to take this exhibit out of the hands of professional curators and your own board of historical advisors. Accepting your stated concerns for accuracy, we trust that you will therefore adjust the exhibit, either to eliminate the highly contentious interpretations, or at the very least, balance them with other interpretations that can be easily drawn from the attached footnotes.

Military and Political Figures Who Dissented From the Terrible Decision

(Link)

President Dwight D. Eisenhower

“…in [July] 1945… Secretary of War Stimson, visiting my headquarters in Germany, informed me that our government was preparing to drop an atomic bomb on Japan. I was one of those who felt that there were a number of cogent reasons to question the wisdom of such an act. …the Secretary, upon giving me the news of the successful bomb test in New Mexico, and of the plan for using it, asked for my reaction, apparently expecting a vigorous assent.

“During his recitation of the relevant facts, I had been conscious of a feeling of depression and so I voiced to him my grave misgivings, first on the basis of my belief that Japan was already defeated and that dropping the bomb was completely unnecessary, and secondly because I thought that our country should avoid shocking world opinion by the use of a weapon whose employment was, I thought, no longer mandatory as a measure to save American lives. It was my belief that Japan was, at that very moment, seeking some way to surrender with a minimum loss of ‘face’. The Secretary was deeply perturbed by my attitude…” (Mandate For Change, p. 380)

“…the Japanese were ready to surrender and it wasn’t necessary to hit them with that awful thing.” (Newsweek, 11/11/63)

Admiral William D. Leahy

(Chief of Staff to Presidents Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman)

“It is my opinion that the use of this barbarous weapon at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against Japan. The Japanese were already defeated and ready to surrender because of the effective sea blockade and the successful bombing with conventional weapons.

“The lethal possibilities of atomic warfare in the future are frightening. My own feeling was that in being the first to use it, we had adopted an ethical standard common to the barbarians of the Dark Ages. I was not taught to make war in that fashion, and wars cannot be won by destroying women and children.” (I Was There, p. 441)

President Herbert Hoover

On May 28, 1945, Hoover visited President Truman and suggested a way to end the Pacific war quickly: “I am convinced that if you, as President, will make a shortwave broadcast to the people of Japan – tell them they can have their Emperor if they surrender, that it will not mean unconditional surrender except for the militarists – you’ll get a peace in Japan – you’ll have both wars over.” (Richard Norton Smith, An Uncommon Man: The Triumph of Herbert Hoover, p. 347)

On August 8, 1945, after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, Hoover wrote to Army and Navy Journal publisher Colonel John Callan O’Laughlin, “The use of the atomic bomb, with its indiscriminate killing of women and children, revolts my soul.” (in Gar Alperovitz, The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb, p. 635)

“…the Japanese were prepared to negotiate all the way from February 1945…up to and before the time the atomic bombs were dropped; …if such leads had been followed up, there would have been no occasion to drop the [atomic] bombs.” (cited by Barton Bernstein in Philip Nobile, ed., Judgment at the Smithsonian, p. 142)

In early May of 1946 Hoover met with General Douglas MacArthur. Hoover recorded in his diary, “I told MacArthur of my memorandum of mid-May 1945 to Truman, that peace could be had with Japan by which our major objectives would be accomplished. MacArthur said that was correct and that we would have avoided all of the losses, the Atomic bomb, and the entry of Russia into Manchuria.” (Gar Alperovitz, The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb, pp. 350-351)

General Douglas MacArthur

MacArthur biographer William Manchester has described MacArthur’s reaction to the issuance by the Allies of the Potsdam Proclamation to Japan: “…the Potsdam declaration in July, demand[ed] that Japan surrender unconditionally or face ‘prompt and utter destruction.’ MacArthur was appalled. He knew that the Japanese would never renounce their emperor, and that without him an orderly transition to peace would be impossible anyhow, because his people would never submit to Allied occupation unless he ordered it. Ironically, when the surrender did come, it was conditional, and the condition was a continuation of the imperial reign. Had the General’s advice been followed, the resort to atomic weapons at Hiroshima and Nagasaki might have been unnecessary.” (William Manchester, American Caesar: Douglas MacArthur 1880-1964, p. 512)

Norman Cousins was a consultant to General MacArthur during the American occupation of Japan. Cousins writes of his conversations with MacArthur, “MacArthur’s views about the decision to drop the atomic bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki were starkly different from what the general public supposed.” He continues, “When I asked General MacArthur about the decision to drop the bomb, I was surprised to learn he had not even been consulted. What, I asked, would his advice have been? He replied that he saw no military justification for the dropping of the bomb. The war might have ended weeks earlier, he said, if the United States had agreed, as it later did anyway, to the retention of the institution of the emperor.” (Norman Cousins, The Pathology of Power, pp. 65, 70-71)

Brigadier General Carter Clarke (The military intelligence officer in charge of preparing intercepted Japanese cables – the MAGIC summaries – for Truman and his advisors)

“…when we didn’t need to do it, and we knew we didn’t need to do it, and they knew that we knew we didn’t need to do it, we used them as an experiment for two atomic bombs.” (quoted in Gar Alperovitz, The Decision To Use the Atomic Bomb, p. 359)

Other dissidents cited in this survey include:

Joseph Grew (Under Secretary of State)

John McCloy (Assistant Secretary of War)

Ralph Bard (Under Sec. of the Navy)

Lewis Strauss (Special Assistant to the Secretary of the Navy)

Paul Nitze (Vice Chairman, U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey)

Ellis Zacharias (Deputy Director of the Office of Naval Intelligence) “Zacharias, long a student of Japan’s people and culture, believed the Japan would soon be ripe for surrender if the proper approach were taken. For him, that approach was not as simple as bludgeoning Japanese cities . . .”

General Carl “Tooey” Spaatz (In charge of Air Force operations in the Pacific)

Columnist Victor Davis Hanson has also mentioned General Hap Arnold, General Curtis LeMay, and Admiral William Halsey.

Summary of Further Catholic Condemnations of the Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki as Immoral

Pope St. John Paul II (9-11-99, to the Japanese ambassador Toru Iwanami): [Hiroshima and Nagasaki should remind the world of] “the crimes committed against civilian populations during World War II . . . true genocides [are] still being committed in several parts of the world.”

Pope St. Paul VI (Peace Day: 1-1-76): “. . . butchery of untold magnitude, as at Hiroshima on 6 August 1945 . . .”

Cardinal James Francis Stafford: “. . . the total warfare that was seen in Nagasaki, Hiroshima, Dresden … that is the wholesale disregard for the civilian populations.”

Ven. Archbishop Fulton Sheen: “When, I wonder, did we in America ever get into this idea that freedom means having no boundaries and no limits? I think it began on the 6th of August 1945 at 8:15 am when we dropped the bomb on Hiroshima.”

Monsignor Ronald Knox: “. . . men fighting for a good case have taken, at one particular moment of decision, the easier, not the nobler path”.

Dr. Warren Carroll (Founder of Christendom College and renowned orthodox Catholic historian): “I don’t agree with the use of the atom bomb against Hiroshima and Nagasaki. You don’t use a weapon in a way that you know is going to kill primarily women and children. It’s a basic principle of moral philosophy that the end does not justify the means.”

Fr. Michael Scanlan (formerly head of the Franciscan University of Steubenville , 1983): “. . . the sinful atrocities of the contemporary world. Whether it be the ovens of Auschwitz and Dachau, the charred bodies of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the ravages of saturation bombing, . . .

John Courtney Murray (prominent thinker on church-state issues): “atrocities, . . . savage . . . paroxysms of violence.”

Evelyn Waugh (famous convert and author): “To the practical warrior the atom bomb presented no particular moral or spiritual problem. We were engaged in destroying the enemy, civilians and combatants alike. We always assumed that destruction was roughly proportionate to the labour and material expended. Whether it was more convenient to destroy a city with one bomb or a hundred thousand depended on the relative costs of production.”

Also, note the opinion of the immensely popular and influential Anglican apologist C. S. Lewis: “The victory of vivisection marks a great advance in the triumph of ruthless, non-moral utilitarianism over the old world of ethical law; a triumph in which we, as well as animals, are already the victims, and of which Dachau and Hiroshima mark the more recent achievements . . .”

Conclusion

I conclude that the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which are defended, as they often are, on mistaken utilitarian calculations which are contrary to both fact and probable fact (as exposited by the highest level military commanders), and with apparent ignorance regarding the facts concerning the nature of the target and the number of innocent civilians killed (which could scarcely have been otherwise, given the target of the center of the city, etc.), and without due regard for Catholic ethical principles, were immoral and unjustifiable.

That’s not to say that this view is a settled dogma in the Catholic Church (I have approached this matter as an ethical one, not a dogmatic one, which is a different level of discussion altogether). Readers are urged to always remember the many qualifying statements from opponents of the bombings, that I have cited. I agree with all of them.

In particular, the justification of “double effect” cannot, I think, be reasonably, plausibly maintained with regard to these bombings. There were simply too many civilian casualties. The scale of death and destruction does not allow it. It is hopelessly naive and muddleheaded and a denial of concrete reality to suggest that these were only peripheral, and non-intentional, while military targets were primary intentions.

Moreover, given the informed opinions of so many that the bombings were not necessary to force surrender or save 500,000 (or whatever the figure) Allied lives (Eisenhower and MacArthur were militarily uninformed, we ought to believe???!!!!), and the nature of the targets, such a view cannot hold water, and must be rejected. From what I have learned, the facts do not justify it. I can certainly be more educated on the subject (time-permitting), but at this point, my prior far less informed opinion has not changed, and has only been greatly strengthened by what I have learned in my studies.

My interest all along has been concordance of the bombings with just war theory, not with calculations of projected future casualties, or how soon the Japanese might have surrendered without the Bomb. I haven’t delved into those issues, by deliberate design, because I wanted to deal with prior premises and preliminary moral considerations first.

President Harry Truman stated:

. . . the Atomic Bomb. It is far worse than gas and biological warfare because it affects the civilian population and murders them by the wholesale.

This was written on January 19, 1953, just before Truman left the Presidency. I included a photograph of the original typewritten document in one of my other papers. So Truman himself thought it was “murder”.

[Go to Part II]

***

(originally 8-25-05)

Photo credit: Maarten Heerlien (9-10-09). “This is a picture of a picture, taken at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial museum. It displays the complete destruction brought about by the atomic bomb on August 6 1945 at exactly 8:15 am.” [Flickr / CC BY 2.0 license]

***