[see Part One]

Wikipedia: “Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki,” is a great resource to further study this issue.

More important resources:

“Hiroshima: Was it Necessary?” (by Doug Long; opposed to the bombings)

NuclearFiles.org (opposed)

The latter includes a very helpful page of documented correspondence concerning the decision

Quotes:

In a private letter written just before he left the White House, Truman referred to the use of the atomic bomb as “murder,” stating that the bomb “is far worse than gas and biological warfare because it affects the civilian population and murders them wholesale.” Barton J. Bernstein, “Origins of the U.S. Biological Warfare Program,” Preventing a Biological Arms Race, Susan Wright, ed. (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1990), p. 9.

– Footnote 97 on the following page –

*****

[The official Bombing Survey Report stated: “Hiroshima and Nagasaki were chosen as targets because of their concentration of activities and population.” More than 95 percent of those killed at Hiroshima and Nagasaki were civilians.]

– on August 9th entry of Chronology page

Another informative article:

“THE DECISION TO USE THE ATOMIC BOMB,” Gar Alperovitz

Excerpts:

(B) A full-scale review of the modern literature concerning the central issues was published in DIPLOMATIC HISTORY in early 1990. Here is its conclusion:

“Careful scholarly treatment of the records and manuscripts opened over the past few years has greatly enhanced our understanding of why the Truman administration used atomic weapons against Japan. Experts continue to disagree on some issues, but critical questions have been answered. The consensus among scholars is that the bomb was not needed to avoid an invasion of Japan and to end the war within a relatively short time. IT IS CLEAR THAT ALTERNATIVES TO THE BOMB EXISTED AND THAT TRUMAN AND HIS ADVISERS KNEW IT.” [Emphasis added; DIPLOMATIC HISTORY, Vol. 14, No. 1, p. 110.]

The writer is not a revisionist; he is J. Samuel Walker, Chief Historian of the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Again, one may challenge Walker’s reading of the literature as of that date, but the notion that to argue the bomb was not needed and that this was understood at the time is somehow outrageous—as some of the postings angrily suggest—is simply not in keeping with the conclusions of many, many studies.

*****

* Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander in Chief of the Pacific Fleet, in a public address at the Washington Monument two months after the bombings stated:

The Japanese had, in fact, already sued for peace before the atomic age was announced to the world with the destruction of Hiroshima and before the Russian entry into the war. . . .The atomic bomb played no decisive part, from a purely military standpoint, in the defeat of Japan. . . . [THE DECISION, p. 329; see additionally THE NEW YORK TIMES, October 6, 1945.]

* Admiral William F. Halsey, Jr., Commander U.S. Third Fleet, stated publicly in 1946:

The first atomic bomb was an unnecessary experiment. . . . It was a mistake to ever drop it. . . . [the scientists] had this toy and they wanted to try it out, so they dropped it. . . . It killed a lot of Japs, but the Japs had put out a lot of peace feelers through Russia long before. [THE DECISION, p. 331.]

* In his “third person” autobiography (co-authored with Walter Muir Whitehill) the commander in chief of the U.S. Fleet and chief of Naval Operations, Ernest J. King, stated:

The President in giving his approval for these [atomic] attacks appeared to believe that many thousands of American troops would be killed in invading Japan, and in this he was entirely correct; but King felt, as he had pointed out many times, that the dilemma was an unnecessary one, for had we been willing to wait, the effective naval blockade would, in the course of time, have starved the Japanese into submission through lack of oil, rice, medicines, and other essential materials. [THE DECISION, p. 327.]

* Private interview notes taken by Walter Whitehill summarize King’s feelings quite simply as: “I didn’t like the atom bomb or any part of it.” [THE DECISION, p. 329; see also pp. 327-329. See below for more on King’s view.]

* In a 1985 letter recalling the views of Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall, former Assistant Secretary of War John J. McCloy elaborated on an incident that was:

very vivid in my mind. . . . I can recall as if it were yesterday, [Marshall’s] insistence to me that whether we should drop an atomic bomb on Japan was a matter for the President to decide, not the Chief of Staff since it was not a military question . . . the question of whether we should drop this new bomb on Japan, in his judgment, involved such imponderable considerations as to remove it from the field of a military decision. [THE DECISION, p. 364.]

* In a separate memorandum written the same year McCloy recalled: “General Marshall was right when he said you must not ask me to declare that a surprise nuclear attack on Japan is a military necessity. It is not a military problem.” [THE DECISION, p. 364.]

GAR ALPEROVITZ AND THE H-NET DEBATE

Founder of Christendom College and renowned orthodox Catholic historian Warren Carroll can be added to the list of those who oppose the nuclear bombings in Japan:

I believe the demand for unconditional surrender was wrong; it made it much more difficult to end the war. And unlike most conservatives, I don’t agree with the use of the atom bomb against Hiroshima and Nagasaki. You don’t use a weapon in a way that you know is going to kill primarily women and children. It’s a basic principle of moral philosophy that the end does not justify the means. So you just don’t do it. We carried it too far. (in “Battling by the Book: Just War Makes a Comeback,” Joe Woodard, National Catholic Register, 10-27-01)

Cardinal James Francis Stafford casually assumed that these bombings were indiscriminate, and hardly examples of a legitimate “double effect” morality:

I think there is an evolution in light not only of John Paul II but Benedict XV, his 1917 proposal for the peace plan, which was rejected by the Allies, and in John XXIII in 1963 against the backdrop of the total warfare that was seen in Nagasaki, Hiroshima, Dresden … that is the wholesale disregard for the civilian populations. (“Cardinal Stafford on War and the Church’s Thinking,” Delia Gallagher, Zenit, 5-22-04)

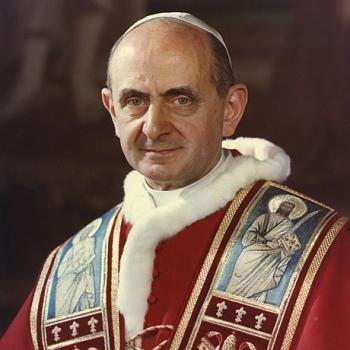

The editorial, “After Hiroshima,” in National Catholic Register, August 21- 27, 2005, noted that Pope St. Paul VI “called America’s use of the atomic bomb ‘butchery of untold magnitude.’ ” It also cites Ven. Archbishop Fulton Sheen:

[I]n his series of talks titled What Now America? [Sheen] said that, by our tacit refusal to recognize the evil of the atomic bomb, Americans became susceptible to a new notion of freedom — one divorced from morality.

‘When, I wonder, did we in America ever get into this idea that freedom means having no boundaries and no limits?’ he asked. ‘I think it began on the 6th of August 1945 at 8:15 am when we dropped the bomb on Hiroshima. … Somehow or other, from that day on in our American life, we say we want no limits and no boundaries.’

Sometimes there is a troubling tendency in American politically conservative circles to be more “American” than “Catholic.” This I vigorously oppose. My view isn’t, “America Right or Wrong,” but rather, “When America is Wrong [by higher, transcendent Catholic standards] It’s Wrong [and not above criticism for fear of silly accusations of a lack of patriotism].”

One who truly loves their country will criticize it when it is wrong, as well as praise it when it is right and just. That’s what the prophet Jeremiah did in ancient Israel, and I daresay that no one loved his own country or suffered more for the sake of it than that holy man did.

The Pope St. Paul VI quote: “‘butchery of untold magnitude,” is from a World Day of Peace Statement of 1 January 1976 (actually written on 18 October 1975), entitled “The Real Weapons of Peace.” Here is the quotation in context (the entire paragraph):

It is no longer a simple, ingenuous and dangerous utopia. It is the new Law of mankind which goes forward, and which arms Peace with a formidable principle: ‘You are all brethren’ (Mt 23:8). If the consciousness of universal brotherhood truly penetrates into the hearts of men, will they still need to arm themselves to the point of becoming blind and fanatic killers of their brethren who in themselves are innocent, and of perpetrating, as a contribution to Peace, butchery of untold magnitude, as at Hiroshima on 6 August 1945? And in fact has not our own time had an example of what can be done by a weak man, Gandhi – armed only with the principle of non-violence – to vindicate for a Nation of hundreds of millions of human beings the freedom and dignity of a new People?”

It’s valid to make such tactical and strategic military calculations. What is not valid, however, is to commit intrinsically immoral acts in order to achieve a good outcome. One can’t do something evil in order to accomplish ultimate good. This is central to Catholic moral theology.

Yet the mentality of many seems to be, “well yeah, it can’t be justified by just war criteria, but it was a difficult situation, and many lives were saved . . . ” [etc., etc., etc.]. So they use that as their basis for condoning what otherwise might be frowned upon even by the same people who advocate doing the immoral act for a good purpose. But unfortunately, that is (I submit) either purely utilitarianism, pragmatism, and situation ethics (which are not Catholic philosophies but Enlightenment and pagan and secular ones), or at least adversely influenced by those outlooks.

I think one ought to take the position of George Weigel, a leading Catholic ethicist and writer on war and peace issues (also biographer of Pope JPII): that it can’t be justified, but nevertheless can be compassionately understood in the context of the extremely difficult situation. I agree with him on this, and also with his position that the Iraqi War is just and that pre-emption is a legitimate development of classic just war theory.

*****

Here’s another good source: “Atromic Bomb Decision: Documents on the Decision to use Atomic Bombs on the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki”

Among the documents is Official Bombing Order of July 25, 1945,”drafted by General Groves. President Truman and Secretary of War Stimson approved the order at Potsdam:

The order made no mention of targeting military objectives or sparing civilians. The cities themselves were the targets. The order was also open-ended. ‘Additional bombs’ could be dropped ‘as soon as made ready by the project staff.’

Dorothy Day’s position on this issue is quite predictable, but perhaps not John Courtney Murray’s (note how he favored nuclear use in Korea)?:

By most estimates, Murray was a moderate, a Rockefeller Republican who hung around with Henry and Clare Booth Luce. Day, the radical, associated with, even lived with, the poorest of our poor in Catholic Worker houses. In the early 1940s, Day nearly buried the Worker movement with her insistence that Christianity demanded non-violence in the face of Hitler’s atrocities, while Murray was arguing, from papal sources, that no Catholic could be a pacifist. Both characterized the bombing of Dresden, Hiroshima, and Nagasaki, in Murray’s terms, as “atrocities,” as “savage … paroxysms of violence.” In the early 1950s, though, Day was jailed for actively demonstrating against nuclear bomb shelter drills, while Murray was arguing that we should use strategic nuclear weapons along the Chinese/Korean border. And in the mid-1950s, in his defense of a moral core at the heart of America, Murray argued from the premise that, in principle, we had solved the problem of poverty. With the Catholic Worker, Day was letting us know what our economy was doing to the poor, to blacks, and to farm-workers. (emphasis added)

More from Catholic apologist Jimmy Akin:

IgnatiusInsight.com: What are the five non-negotiables? How were they selected?

Akin: The [Catholic Answers Voter’s] guide identifies five issues on which Church teaching has been adamant: No Catholic can in principle support abortion, euthanasia, embryonic stem cell research, human cloning, or homosexual “marriage.” These issues were selected because there are currently under discussion in American politics and there are clear Magisterial statements indicating that Catholics can never support these issues.

IgnatiusInsight.com: Are these the only such issues?

Akin: Those are the issues in American politics in our day that the Holy See has indicated are non-negotiable. Had the guide been written in a different age, when different issues were under discussion or different Magisterial statements were available, a different set of non-negotiables would emerge. For example, if U.S. leaders were presently advocating the targeting of innocent civilians—as happened at places like Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and Dresden—then the guide would cover the fact that you can never deliberately target civilians and must seek to minimize civilian casualties. But government leaders today aren’t advocating the targeting of civilians.

IgnatiusInsight.com: What if there is no candidate who is “right” on all the issues?

Akin: The guide covers this. It points out that there are situations where one must seek to limit the damage done to society by voting for “the lesser of two evils” when there is no perfect candidate.

IgnatiusInsight.com: You’re a Catholic apologist and the author of articles and books on apologetics. Catholic Answers is an apologetics apostolate. How would you respond to claims that publishing a Voter’s Guide is outside the purview of your organization’s mission?

Akin: I would say someone making such a claim does not understand what Catholic apologetics is: It is the defense of Catholic teaching and practice. To make a defense of these, you have to explain clearly what they are. I can’t defend the doctrine of the Trinity against Mormon misrepresentation if I don’t clearly articulate the doctrine of the Trinity. Today Catholic moral teaching has come under attack, both by individuals outside the Church and even by some within it, who want to confuse and mislead Catholics about what their faith requires. It is my job as an apologist to defend the Church’s teaching, including its moral teachings regarding political involvement, by clearly articulating what those teachings are and by answering challenges to them. (emphasis added)

Amen, Jimmy!

Ronald Knox:

After the two cities were destroyed, Knox was about to propose a public declaration that the weapon would not be used again, when he heard the news of the Japanese surrender. Instead he sat down and wrote God and the Atom, an astonishing book, neglected at the time and since, but as important for sceptics as for Christians.

An outrage had been committed in human and divine terms, Knox thought. Hiroshima was an assault on faith, because the splitting of the atom itself meant “an indeterminate element in the heart of things”; on hope, because “the possibilities of evil are increased by an increase in the possibilities of destruction”; and on charity, because – this answers those who still defend the bombing of Hiroshima – “men fighting for a good case have taken, at one particular moment of decision, the easier, not the nobler path”.

*****

Evelyn Waugh:

. . . as Evelyn Waugh put it when writing about Knox’s book in 1948: “To the practical warrior the atom bomb presented no particular moral or spiritual problem. We were engaged in destroying the enemy, civilians and combatants alike. We always assumed that destruction was roughly proportionate to the labour and material expended. Whether it was more convenient to destroy a city with one bomb or a hundred thousand depended on the relative costs of production.”

C.S. Lewis:

The victory of vivisection marks a great advance in the triumph of ruthless, non-moral utilitarianism over the old world of ethical law; a triumph in which we, as well as animals, are already the victims, and of which Dachau and Hiroshima mark the more recent achievements… (‘Vivisection’, God in the Dock, edited by Walter Hooper, Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans, 1970, pp. 224, 225, 228)

One cannot kill civilians. You can carry out a war if it is against combatants. Then you are allowed to kill, and kill many if needs be. But when it comes to deliberately killing non-combatants then it is in clear violation of Catholic just war teaching, whether this “saves lives” in the long run or not. And that is why I cannot sanction what we did.

I have condemned the bombing of Dresden, too, in my comments, and also the fire-bombings of Tokyo. None of these things can be justified, and in 1937 all of the Allies would have thought such acts unthinkable and immoral. They were right then, but the horrors and stresses of war made them get down into the gutter with evil enemies. That’s unfortunate because WWII was a just cause to fight if ever there was one in history. We were dealing with spectacularly evil, genocidal, maniacal opponents bent on world conquest and the destruction of civilization and national sovereignty.

Matthew (words in blue) asked some questions:

The question though is were they were intended to be killed or an unfortunate side effect? It doesn’t mean the people who dropped the bomb didn’t know civilians would be killed but whether they intended it. That would still be the question.

I don’t see how they could not know it. I think that to even ask the question itself is absurd. They knew what the bomb was capable of, and they deliberately dropped it on the center of the cities. So if they didn’t “intend” this; then it is awful hard to figure out what they did intend. It’s as if we think they had no idea what would happen. Since that makes no sense, we must conclude that they intended such a result.

The other thing I can think off is an invasion would have killed a lot of civilians as well just one by one. So we would have to condemn that as well. End result – we don’t fight Japan cause it’s just so darn hard to avoid killing the innocent. But then we can’t defeat them :-(.

This is a whole other discussion, but if we had invaded, and the Japanese had starved themselves or committed mass suicides or something (while we were fighting the armies and soldiers), then at least that would not be our direct causation or will, whereas the bomb leaves no doubt whatsoever as to result and causation. We willed it; we did it, as the agents; we are responsible. But if they wanted to be crazy and starve themselves or whatever, we can’t be blamed for that, anymore than we can be blamed for suicide bombers in Iraq, who might do what they do (in their own crazed minds) because of “us.” They made the immoral choice. We aren’t culpable for that choice. We’re trying to fight terrorists precisely because they are evil and murder innocent bystanders. Yet we turn around and rationalize that our killing of 200,000 civilians is somehow “moral.” It’s moral insanity and special pleading.

This has nothing to do with whether it was moral or not but I thought I would mention that the Nagasakians accepted it as a holocaust that they had to pay for what their nation had done.

That would be a normal human reaction, after having come to one’s senses, but it has no relation to whether the action was morally right or not.

What do you think of this idea of what they should have done Dave? What they should have done is blown the top off Mt Fuji to demonstrate the power of the bomb. And then landed one in a similar place to cow them into complete submission. A kind off “if you don’t well drop more of them and this time right on top of you …” Something they knew they wouldn’t do (and would not be able to do having run out of bombs).

Something along those lines would have been morally neutral. It certainly could have been tried. But we went right to mass murder because we had gotten very used to it and comfortable with it by then.

Can I quickly bring up something else? Do you think that the first Gulf War was a just war? I do. In fact is one the most blatantly just of all time.

Absolutely. The causes were just and the promulgation was, because of smart bombs, etc.

Here we have an evil nation with an unbending dictator attacking a smaller innocent nation that can’t defend itself. So clearly we have a case of self defence (albeit by proxy in this case which was necessary as Kuwait couldn’t defend itself). Seeing authorities have often been cited in this whole discussion (and that is legitimate) could I ask why JPII opposed this war? I’ve never worked that one out. I think he was wrong (sorry – couldn’t think of a pc way to put it). Do you want Kuwait ruled by an evil dictator? Would you have been able to “convince” Saddam Hussein back in 1991 to kindly move off please without military intervention?

This gets very complex, but essentially, the popes feel themselves to be figures of peace, so they routinely condemn wars, because they are striving for the ideal world situation. They talk about the need for peace among nations. Often, this is done in a very general way, so as not to condemn particulars, which is why I had to look hard for a citation from Pope John Paul II which specifically condemned the bombings in Japan as immoral actions. Popes know that the ultimate authority for declaring war (or capital punishment) rests on nations, as God gives them that right (in Romans 13). But someone needs to talk about the ideal of world peace. Likewise, Jesus didn’t engage in military actions, because it wasn’t His purpose, but He did not forbid the same.

Now, if Pope St. John Paul II was very specific in his condemnation of the Gulf War as immoral, I would have to look more closely to see the grounds, and that would be an interesting discussion itself.

* * *

See this page for a chilling, fact-filled scientific-type summary of what the bombings in Japan actually caused to happen to people and things:

Pope St. John Paul II condemned the bombings, and strongly implied by comparison that they were genocidal, as shown in Catholic World Report, Nov. 1999 (vol. 9, No. 10): “World Watch”

JAPAN

Lessons of Hiroshima, Nagasaki Pope sees “crimes” in atomic bombing

As he greeted a new ambassador from Japan, Pope John Paul II said that Hiroshima and Nagasaki should stand as “symbols of peace” and should remind the world of “the crimes committed against civilian populations during World War II.”

Receiving the new ambassador, Toru Iwanami, on September 11, the Pontiff lamented that “true genocides” are “still being committed in several parts of the world” today. He expressed his regret that the “culture of peace is still far from being spread throughout the world.”

The Pope also invoked the 450th anniversary of the arrival of St. Francis Xavier in Japan, which is being celebrated this year. He said that the life of St. Francis should point to “the importance of spiritual freedom and religious liberty,” and he saluted “the attitude of tolerance” toward religion which now prevails in Japan.

Fr. Michael Scanlan (formerly head of the Franciscan University of Steubenville) has written (link now defunct; emphasis added):

In addition to dealing with the internal reality of sin and the need for conversion, the call to be penitents enables one to deal effectively with the sin in the world around us. Men and women frequently experience depression when they allow themselves to experience the sinful atrocities of the contemporary world. Whether it be the ovens of Auschwitz and Dachau, the charred bodies of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the ravages of saturation bombing, the starvation of Bangladesh and Calcutta, the destruction of family life and morals, the prevalence of abortion and pornography, the teenage drug addicts and alcoholics, the crime waves, the imminence of a nuclear holocaust, the practical atheism of pagans and nominal Christian peoples, or the individual tragedies that touch all our lives, the sin around us is real and must be faced. Who does not experience powerlessness in the face of all this?

If the “evidence” that civilians were not targeted is so good, then why did Truman himself call the act (he is the guy who decided to drop the bombs, after all) “murder” (and I had already previously posted this)?

*****

In a private letter written just before he left the White House, Truman referred to the use of the atomic bomb as “murder,” stating that the bomb “is far worse than gas and biological warfare because it affects the civilian population and murders them wholesale.” Barton J. Bernstein, “Origins of the U.S. Biological Warfare Program,” Preventing a Biological Arms Race, Susan Wright, ed. (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1990), p. 9. — Footnote 97 on the following page

*****

[The official Bombing Survey Report stated: “Hiroshima and Nagasaki were chosen as targets because of their concentration of activities and population.” More than 95 percent of those killed at Hiroshima and Nagasaki were civilians.] — on August 9th entry of Chronology page –

Thus the bombings clearly violate the Catholic prohibition of indiscriminate bombing of large areas, and populated areas, which is expressed at Vatican II and in the CCC (which are magisterial).

We should simply have conducted ourselves in World War II according to the just war rules and generally accepted norms of combat situations. We opted to lower ourselves to the unethical level of our enemies because the road to victory was easier that way. But that doesn’t make it moral. If we avoid deliberately killing civilians, apply proportionality and double effect, etc., we can conduct a just war without any necessity of pacifism, which is required neither by Catholicism, Christianity in general, nor the Bible.

We would have still had a practical problem of how to defeat such a fanatical army through moral means, but neither a logical nor a moral problem.

I ran across another interesting and germane article:

Bomb Shelter: The enduring morality of Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and the end of World War II, by Duncan Currie [link now defunct]:

. . . WHETHER OR NOT Hiroshima and Nagasaki were legitimate military targets – and there’s a raft of evidence suggesting they were – U.S. policymakers clearly knew the bombing would produce tens of thousands of civilian fatalities. In that sense, and for argument’s sake, let’s concede that the bombing represented a deliberate massacre of Japanese civilians. How does that affect its morality, if at all?*A great deal, argues Ramesh Ponnuru [“NR Senior Editor”] of National Review, himself an eloquent critic of Truman’s decision to nuke Japan. “The conservative error,” Ponnuru writes, “is to assume that the intentional killing of civilians is justified in order to avert a greater number of deaths.” It would be a most unfortunate “change,” he adds, “if we were to intentionally target civilians whenever we thought that doing so would hold our military casualties down (or even hold the total number of civilian and military casualties down).”

To continue citing this article:

[I]t is not necessary to make a definitive judgment that Truman made the wrong choice in order to be troubled by the justifications that have been made for that choice – and to wonder about their implications for the war on terrorism. (Most of those justifications stipulate that neither Hiroshima nor Nagasaki were conventional military targets: that the point was to break Japan’s will by showing how much we could destroy. And they do not treat our warning leaflets as strong evidence that the civilian deaths were unintended. I will make these assumptions my own, both because the balance of evidence suggests that they are true and because I am trying to analyze the arguments proffered for intentionally killing civilians.) . . .[T]he question would remain whether this type of military practice is (and was) justified. To the extent that the intentional killing of civilians had become a routine military technique – and Churchill’s qualms about it are among the reasons for refusing to endorse that view completely – that might mitigate Truman’s culpability for making the wrong choice (if it was the wrong choice). But it would not yield the conclusion that his choice was right. We might well conclude that Hiroshima and Nagasaki were part of a class of immoral, though understandable, acts committed by the good guys during World War II.

Some commentators . . . have cited atrocities committed by the Japanese by way of justifying the bombings. But that can’t be right, at least as the point is generally made. The war crimes of Japanese soldiers are not a good reason to kill a child in Nagasaki. The barbarism of an enemy is an added reason to stop him, but whether any means of stopping him are acceptable is precisely what is at issue. . . .

To proponents of the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the opposition looks absurdly unrealistic. For them, it has a whiff of pacifism about it. But even though most Americans would, if asked, say that they think it was right to drop the atomic bombs, it is not obvious that the proponents’ arguments really do track well with our ordinary moral intuitions about war. (I am not implying here, by the way, that our moral intuitions are always justified.) At least, they do not track with our normal military practices. . . .

National Review has had shifting views on the morality of Hiroshima and Nagasaki: sympathetic to the moral objections in the late 1950s, glibly dismissive of them in the late 1980s.

It is true that there was a Japanese army base on the outskirts of Hiroshima—it was a major staging area for the invasion and occupation of Southeast Asia. But historians have questioned the claim that the existence of the military base made Hiroshima a “military target.” The only text I have on the bombing handy is Lifton and Mitchell, Hiroshima in America: Fifty Years of Denial – not the most objective source – but the two most prominent historians who have written on the development and use of atomic weapons, Richard Rhoades and Gar Alperovitz, agree on many of the basic facts.On the military nature of the bombing: It is doubtful that the bomb dropped on Hiroshima was intended for any of the military bases. The bomb was dropped in the center of the city, miles from either the army or navy base. Given that the destructive capability of the bomb was not fully known, it is doubtful that the air force would have targeted the center of town if the bases were the intended targets. But few historians have ever argued that the bombing of Hiroshima was intended as a strategic, tactical strike on a particular target. . . .

Hiroshima was almost untouched during the war, primarily because of its limited military significance but also because of its religious and cultural significance. Bombing the city, it was thought, would send the message that no city would be safe if the Japanese forced the Americans to continue the fight.

Of a city area of over 26 square miles, only 7 square miles were completely built-up. There was no marked separation of commercial, industrial, and residential zones. 75% of the population was concentrated in the densely built-up area in the center of the city.Hiroshima was a city of considerable military importance. It contained the 2nd Army Headquarters, which commanded the defense of all of southern Japan. The city was a communications center, a storage point, and an assembly area for troops. . . .

The center of the city contained a number of reinforced concrete buildings as well as lighter structures. Outside the center, the area was congested by a dense collection of small wooden workshops set among Japanese houses; a few larger industrial plants lay near the outskirts of the city. The houses were of wooden construction with tile roofs. Many of the industrial buildings also were of wood frame construction. The city as a whole was highly susceptible to fire damage. . . .

At the time of the attack the population was approximately 255,000 . . . [75% of that – population in the center – would be 191, 250] . . .

Nagasaki [the article later gives its population as 195,000] . . .

The bomb exploded high over the industrial valley of Nagasaki, almost midway between the Mitsubishi Steel and Arms Works, in the south, and the Mitsubishi-Urakami Ordnance Works (Torpedo Works), in the north, the two principal targets of the city. . . .

At Nagasaki there were no buildings just underneath the center of explosion. The damage to the Mitsubishi Arms Works and the Torpedo Works was spectacular, but not overwhelming. There was something left to see, and the main contours of some of the buildings were still normal. . . .

In Hiroshima over 60,000 of 90,000 buildings were destroyed or severely damaged by the atomic bomb; this figure represents over 67% of the city’s structures. . . .

As intended, the bomb was exploded at an almost ideal location over Nagasaki to do the maximum damage to industry, including the Mitsubishi Steel and Arms Works, the Mitsubishi-Urakami Ordnance Works (Torpedo Works), and numerous factories, factory training schools, and other industrial establishments, with a minimum destruction of dwellings and consequently, a minimum amount of casualties. Had the bomb been dropped farther south, the Mitsubishi-Urakami Ordnance Works would not have been so severely damaged, but the main business and residential districts of Nagasaki would have sustained much greater damage casualties.

[this, to me, suggests that the bombing of Nagasaki was relatively more justifiable, but not enough to overcome the objection of just war criteria]

. . . The Nagasaki Prefectural report describes vividly the effects of the bomb on the city and its inhabitants:

“Within a radius of 1 kilometer from X, men and animals died almost instantaneously and outside a radius of 1 kilometer and within a radius of 2 kilometers from X, some men and animals died instantly from the great blast and heat but the great majority were seriously or superficially injured. Houses and other structures were completely destroyed while fires broke out everywhere. Trees were uprooted and withered by the heat.

“Outside a radius of 2 kilometers and within a radius of 4 kilometers from X, men and animals suffered various degrees of injury from window glass and other fragments scattered about by the blast and many were burned by the intense heat. Dwellings and other structures were half damaged by blast. . . .

There has been great difficulty in estimating the total casualties in the Japanese cities as a result of the atomic bombing. The extensive destruction of civil installations (hospitals, fire and police department, and government agencies) the state of utter confusion immediately following the explosion, as well as the uncertainty regarding the actual population before the bombing, contribute to the difficulty of making estimates of casualties.

[the entire article contains just about anything anyone would want to know about the effect of the bombings]

The bombing order was against cities not specific military targets. The cities selected were Kyoto, Hiroshima, Yokohama, and Nagasaki.The overriding conclusion from my review of the weapon effects at Hiroshima is that this weapon was intentionally designed and deployed to kill or maim as many humans as possible in residential housing (or unprotected outside) over the widest possible area for the weapon’s size (while minimizing radiation effects from contaminated debris being thrown up into atmosphere). Since much of the Hiroshima industrial capacity was also located in unreinforced brick structures this type of airblast would also destroy any unreinforced masonry or brick buildings. One of the most flammable items on a person is their hair and clothing.

Much of the clothing at this time was cotton (or blended cotton) which would be considered highly flammable. I suddenly came to the realization that the intent of propagating a fireball at this height was to be able to set fire to a person’s clothing (and all types of fabrics) at relatively long distances from the blast’s epicenter. The airblast would be felt for miles (blowing out windows and damaging most all structures by cracking the walls) and terrorize the remaining population. Hence, the description by those who survived of seeing burned bodies everywhere (or charred skeletons) and skin that was shredded into strips is consistent with the bombing order to hit a populated city in the center without specific regard to military objectives.

From: Detroit News (August 6, 2005)

“60 years later, questions about Hiroshima still split U.S.and Japan” By Joseph Coleman [link now defunct]

Although Hiroshima is often portrayed as a purely civilian target, it had a long history as an army city and was home to tens of thousands of soldiers as well as the headquarters of the Fifth Division and the Second General Army.But it had no munitions factories, and the fact that it had never been bombed with conventional weapons suggests it was low on the list of Allied military targets. Nagasaki, meanwhile, was only bombed after cloud cover made the preferred choice, Kokura, too difficult to hit accurately.

And a blog entry [link now defunct]:

Tokyo had been fire bombed March 9-10, 1945 and some 83,000 civilians burned to death and thousands homeless. US B29 bomber crews commented on the stench of burning bodies when they made low level passes over Tokyo. “Brigadier General Bonner Feller described the air raids as the most ruthless and barbaric killings of non-combatants in all history”“It would be a mistake to suppose that the fate of Japan was settled by the atomic bomb. Her defeat was certain before the first bomb fell.” (UK Prime Minister Winston Churchill.)

Field Marshal Montgomery ( Commander of all UK Forces in Europe) wrote in his History of Warfare: It was unnecessary to drop the two atom bombs on Japan in August 1945, and I cannot think it was right to do so …. the dropping of the bombs was a major political blunder and is a prime example of the declining standards of the conduct of modern war.

It is intrinsically immoral to deliberately kill civilians (not counting unintended effects of bombing a military target). It’s as simple as that. So one cannot do it. An embargo is not intrinsically immoral if, e.g., food supplies are allowed in. We could have made sure they stayed there and didn’t harm anyone else. If they wanted to then kill themselves, then that would be their fault, not ours (we would not be the deliberative agent of causation).

But in a nuclear strike, all the noncombatants have no choice: they are incinerated or irradiated, and this is an evil act. PERIOD. Why is this so difficult for some to grasp? It was wrong for the Germans to bomb London, and so it was wrong for us to bomb Dresden, Tokyo, and Hiroshima and Nagasaki. And that is because these are intrinsically immoral acts, regardless of the circumstances they occur in.

Photo credit: President Harry S. Truman (c. 1947), “Give ’em hell, Harry!” [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]