Hiroshima and Nagasaki fail the Catholic test of “double effect” because they involved the killing of over 200,000 civilian noncombatants. Such an act is condemned in traditional just war criteria which forbids deliberate targeting of such non-military populations. The exceedingly weak counter-argument given by proponents is that these cities had military installations (President Truman absurdly referred to the city of Hiroshima as a “military base”). These were the targets, so we are told, not the civilian population; therefore the dreadful result of killing them was not willed and is supposedly covered under the “protection” of the principle under consideration.

I have contended that such a justification is ludicrous and an example of rationalizing special pleading of the worst kind. It simply can’t be sustained, given nuclear technology, even if relatively unknown at the time. If we grant this “lessening of culpability due to ignorance” for Hiroshima, we still could not do so for Nagasaki, since it was then known what would happen.

Furthermore, the target areas (the centers of both cities) and the knowledge that the effect of the bombs spread outwardly from ground zero to cover a known area of a particular estimated size, and the obvious fact that cities contain citizens and population (read: people, persons, human beings; read, “including many elderly men, women, and children”), make it quite implausible (I think, virtually impossible) to maintain that those who ordered such a strike were targeting only military installations and not also people.

Moreover, terror bombing or carpet bombing of cities with known effects had already occurred (particularly in Dresden, Germany and in Tokyo). It is equally absurd to argue that those strikes were not intended to target populations as well as military production facilities, bases, etc. This being the case, and the immediate precedent, it is difficult to make an argument that somehow Hiroshima and Nagasaki were instances of a strike wholly different in nature and intent from Dresden and Tokyo.

If indeed only the military targets were in mind, then why drop these horrific weapons on the center of the city? Was that the way to take out the most military targets? I have read that the bulk of these targets were on the outer peripheries of the city, not in the center. If the goal was to minimize civilian casualties, is not the center of the city the very worst selection for this end? The intent was clearly to kill as many people as possible along with taking out whatever military targets were there. Of course, those who do such an evil thing will maximize the military significance and minimize the human cost, but the facts remain what they are and cannot, in my opinion, be gotten over.

To sum up, then:

1) Deliberately killing civilians in wartime is wrong.

2) The bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki did that (to the tune of 200,000 + casualties).

3) It cannot plausibly be maintained that this was a non-intended effect of a moral good (taking out military installations) because of the nature of the weapon, where it was targeted, and immediate historical precedent.

4) Therefore, it was an evil act, since contrary to Catholic just war criteria, and inability of justification by this criterion of double effect.

5) Conclusion: the bombings violate double effect by being morally bad and not at all indifferent.

I think it is impossible and ludicrous to maintain that 200,000 deaths as a result of a bomb of mostly-known proportions and effects were not “willed,” but merely “permitted”. How can one drop such a weapon and claim to not know that such a result in human cost would happen? As I stated previously, one can’t simply play word games and act as if the magic words “military target” wrap up all the difficulties of this cynical, downright malicious (from the standpoint of the victims) reasoning.

The second sentence is also quite applicable and damaging to the proponents’ position, thought not fatal in and of itself, due to the nature of probabilistic or contingent or theoretical calculations of what would happen in the future. As many high military figures felt at the time (Eisenhower, MacArthur, Nimitz, Halsey, Carter Clarke: who was in charge of the radio intelligence summations; also former President Hoover, etc.), surrender could have been achieved by the end of 1945 without recourse to such horrible measures. There was certainly enough opinion and evidence along these lines for us to have at least more seriously considered such an option, in accord with this principle.

Or else, I suppose proponents could simply argue that all these military experts were ignorant, misguided, acting on emotions alone (as if the pro-bombing crowd did not have a large amount of emotions clouding their reasoning, too), or that they only reported their supposed feelings anachronistically, and after the fact (due to the Cold War, the second-guessing of hindsight, etc.). Some people seem to consider themselves able (as a non-military and non-academic persons), 60 years after the fact, to better make such judgments than folks like Eisenhower and MacArthur. Is that not exceptionally presumptuous?

If we grant that President Truman acted in good faith, with good motives (as I freely do), then we must also grant that those opposed to the decision at the time were equally in good faith, with roughly equal the information needed to make the decision one way or the other. This was not a unanimous consensus at the time, however one wishes to slant or spin it. In other words, many thought that we could achieve the good end without the bad effect of what the bomb in fact caused. it was a viable option; therefore it should have been seriously considered and (I say) chosen as the more moral option of the two.

The good end desired (the surrender and thus the end of the wanton slaughters of the Japanese army and suicides even of Japanese civilians) was promptly achieved. So far so good. The good effect was also produced by the action; yet it was also produced by the bad effect of the action (the mass killings convinced the Japanese of the futility of continuing). Thus, this would seem to suggest that Hiroshima and Nagasaki do not meet this particular just war criterion.

And thus we arrive at the crux of the matter: the previous state of affairs being true; therefore a good end was achieved by a bad means, and this is not allowed in Catholic moral theology. Therefore, the bombings are unjustifiable once again, on this separate and distinct ground. If, to speak theoretically, somehow we had had the technology then to wipe out 200,000 Japanese soldiers, and very few civilians as unintended “collateral damage,” then the act would have been quite acceptable by these standards. But since the dead were some 95% civilians, the rationale doesn’t wash (as that is the very opposite ration of what should be for this to be a moral act). It was, therefore, an evil act. And one must not commit evil, even for the achievement of a great good. Such is not Christian ethical thought. Period.

As in the previous example, it cannot be reasonably argued that the bombings were morally good or neutral acts themselves. The double effect principle itself rules out using a bad, evil, immoral act for the purpose of producing good effects, no matter how good the effects may be. A good effect indeed was produced (the surrender), but the means to achieve it were evil. Therefore, they are not justifiable. Evil effects were willed by means of inherently evil acts.

I freely grant the good intentions and good faith of those who disagree with me on this. But I cannot agree with their moral logic. In my opinion, it violates traditional just war criteria, the specific principle of double effect, and also the standards of the larger natural law, whereby it is instinctively known by virtually everyone that deliberate killing of women and children (in wartime as well as outside of it) is inherently wrong.

It’s been argued that one might obliterate the civilian / soldier distinction in a militaristic society like wartime Japan, with its suicides and maniacal tendencies, etc. But how could a three-month-old baby be part of that, or a senile old woman, or a mentally ill man, etc.? Even if we were to grant that (which would take some doing), there would still be many exceptions to the rule. The bombings, therefore, would still have to be judged as immoral, since they involved the killing (and I am not averse to using the word “murder” after having established the ethical reasoning chain above) of many “innocents” in terms of the war.

This is a far different scenario from a smart bomb taking out a munitions factory (the intent), with part of the shell skidding off to a house a mile away and burning it and its inhabitants (not the intent at all). That is tragic but justifiable. Dropping a nuclear bomb into the center of a heavily-populated city is not.

***

Gar Alperovitz noted the following facts:

Brigadier Gen. Carter W. Clarke, the officer in charge of preparing MAGIC intercepted cable summaries in 1945, stated in a 1959 interview:

we brought them [the Japanese] down to an abject surrender through the accelerated sinking of their merchant marine and hunger alone, and when we didn’t need to do it, and we knew we didn’t need to do it, and they knew that we knew we didn’t need to do it, we used them as an experiment for two atomic bombs.” (See p. 359, Chapter 28)

Perhaps the Japanese would not have surrendered very soon after August 1945 without the bombs. Everyone must speculate and there can be no sure answer (as in all “what if?” historical inquiries).

I have simply shown that many high-placed military figures at the time did not favor the bombings, and indeed felt that surrender would occur without it. They know a lot more about this than lay observers, sitting in armchairs, 60 years later, which is why I keep appealing to them.

On the other hand, ultimately, my judgment on this isn’t based on utilitarian, pragmatic calculations as to whether Japan would surrender or not. I think the bombings were intrinsically immoral because of the numbers of civilian casualties involved. Therefore, they could have no ethical justification, period (not even on a secular absolutist basis), no matter how good the perceived or probable end might be.

No one could have not known this (the high casualties of noncombatants), and I have provided some strong evidence that indeed it was known at the time, and that even proponents of the bomb cannot get over that fact. Cities of multiple thousands of inhabitants are somehow thought to be “military targets” and the unintended civilian casualties as secondary to the destruction of some military plants (as if this justifies the wholesale slaughter). I find it absolutely outrageous. I understand the reasoning (as I used to hold it myself) and do not cast aspersions upon the motivations of proponents, but I cannot support the thing itself, because I don’t find the rationales offered to be based on Catholic just war principles.

I find this position as outrageous as the following analogy (to use the example of my own city, which I know something about):

In the Detroit metro area is Willow Run Airport. In that area, many bombers were manufactured by Ford Motor Company, and played a key role in the air war (my father, incidentally, flew 24 missions over Germany as a top gunner in the Canadian / Royal Air Force, and I have always been very proud of that part of his life). We also have military bases (of what relative importance I know not).

But say for the sake of argument that these bases were very important, along with the Willow Run facilities which were undeniably very important. By the reasoning of some proponents of these bombings (and alas, Truman’s), one could detonate an atomic bomb halfway between Willow Run and Selfridge Air Force Base, which location would be approximately in the very center of Detroit proper. By this incomprehensible reasoning, Detroit (a city of 2 million in the WWII era) is a “military base.” Therefore, to strike at its center (as in the examples of Hiroshima and Nagasaki) is to strike military targets; therefore, not intending to kill civilians (who just happen to unfortunately be there). Their deaths are justifiable by the principle of double effect.

So say that, roughly a third of the inhabitants of metro Detroit (including my mother and her parents at that time, and possibly my father’s parents) would be killed (approximately the ratio at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, without doing the exact math). This would amount to some 670,000 deaths. But these are all “collateral damage” because, after all, they were not the “targets”: Willow Run and Selfridge were.

It’s double effect, you see. If 200,000 can be killed by this absurd moralistic rationalization, why not 670,000? Just as if one abortion is legal (the intrinsically immoral taking of an innocent life), why not 1.5 million a year? Once that line is crossed there is no end. This is why the Catholic Church opposes it from the outset, on principle, and in accord with basic principles of justice inherent in the natural law, known to all conscientious men. I think the analogy above is quite apt and that it shows once again the moral absurdity of such a position.

As for Truman’s subjective culpability, I make no judgment on that. I believe that he was in an extremely difficult situation, and that we must allow for that, and that God certainly will, in His infinite wisdom. I am not about condemning individual motivations in this discussion.

I understand quite well, I think, the honorable motivations and intentions of those who disagree with me on this (again, having once held the same position myself, as is so often the case). I simply disagree that the position can be harmonized with Catholic moral principles. America decided in its carpet bombing policies, to abandon just war criteria. The reasoning was that one must oppose total war by total war. This is immoral and indefensible. Understandable in those incredible circumstances, sure, but ethically indefensible . . .

Such an analogy as mine above is intended as a reductio ad absurdum (one of my favorite rhetorical techniques in dialogue). It is incumbent upon bomb proponents to reply to that, in order to show that what it suggests is false; viz., that the analogy does not prove the absurdity of that which it seeks to overcome in the reductio.

Furthermore (and this is a crucial point in understanding my approach) I cited many prominent Catholics (and at least one very prominent Anglican layman), in my initial article, for the following reasons:

1) Because they (in most cases) know more about the issue than I do.

2) To show that this position is indeed the Catholic mainstream one, not some fringe or “left-wing” or quasi-pacifist position.

3) To reiterate that a Catholic’s opinions on such momentous ethical and socio-political issues are formed within the matrix and framework of Catholic community and the magisterium (as opposed to pure private judgment) , even if the issue is not technically one of dogma and non-negotiable. Catholics may differ, but they are still Catholics, who must form such opinions of conscience and ethical principle in light of the Church’s teaching and guidance. If one, therefore, shows little outward sign of doing so, then one must be guided towards the proper sources that he has been overlooking in forming his opinions. And so I am presently providing that service.

I’m not brash enough to think that my own bald opinion on such a momentous matter is enough to persuade or carry any weight with anyone. Therefore, I cite scholars and leading figures in the Church. There is nothing wrong in citing people who have more knowledge and expertise on a subject.

One can distinguish between:

1) Making a strong assertion about some Catholic teaching as a matter of one’s own opinion.

and:

2) Making out that this opinion is dogmatic Catholic teaching with regard to the particular under consideration and that no one can possibly disagree.

Karl Keating wrote:

The atomic bombings of Nagasaki and Hiroshima, like the fire bombings of Dresden and other German cities, cannot be squared with Catholic moral principles because the bombings deliberately targeted non-combatants.

I think this can easily be interpreted as an instance of #1 and not #2. Perhaps it could have been worded better (as is usually the case with almost all writing), but I don’t think he was being “dogmatic”. The same applies to the Catholic Answers Guide. To state one’s opinion (even if strongly held) that a certain Catholic principle was violated in Instance X is not the same as asserting that one’s opinion on the matter is itself magisterial and unable to be dissented against without being a lousy Catholic.

We are talking about bombs detonated over the center of cities with multiple thousands of people. To say that this was not a deliberate targeting of civilians as well as military materials is absurd. By this reasoning we could explode a bomb over Baghdad or some other Iraqi city if a significant number of terrorists resided within, and simply say that we were targeting the terrorists, and had no intention of killing anyone else.

***

(originally 8-28-05 and 9-5-05)

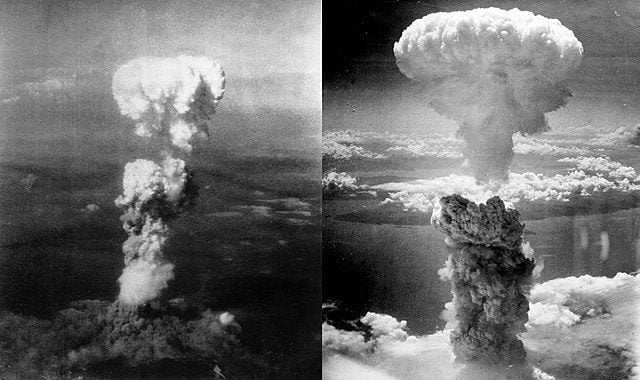

Photo credit: left: nuclear bombing of Hiroshima (8-6-45), taken by George R. Caron / bombing of Nagasaki (8-9-45), taken by Charles Levy [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

***