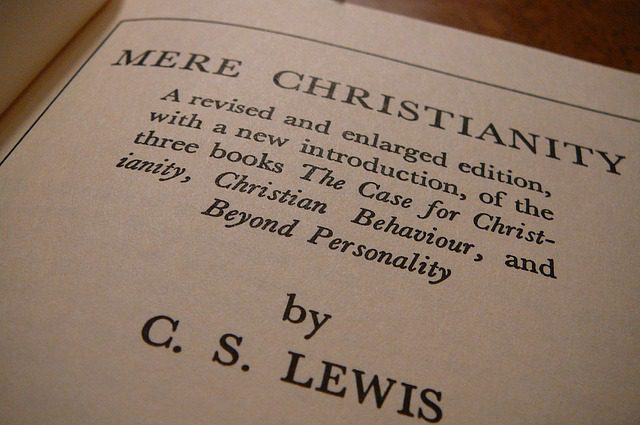

Mere Christianity, C. S. Lewis (1952) [available to read online]

Lewis is my favorite writer. I read this in the late 70s, before I seriously started my own apologetic writing and evangelism. It has influenced so many. The role it played in my own life was to give me a simple but thoughtful introduction to a “thinking man’s Christianity.” Thus it was a key step prior to apologetics proper; rather, it showed me how rationality and faith were not antithetical to each other (one of the foundational principles of the apologetics enterprise).

At the time I was in college and was attending an evangelistically oriented Lutheran church, which was great for newly committed Christians of the low church evangelical variety (this particular church was far more “evangelical” than Lutheran) but not quite as good for developing the Christian mind (though it did have a great little bookstore of numerous Lewis and Dietrich Bonhoeffer books).

Moreover, the book influenced my nascent ecumenism, since it was an attempt to present what all Christians had in common. This always stuck with me, in my Protestant days, and since my conversion to Catholicism. I have emphasized ever since (it has even become one of my leading “themes”) that ecumenism or Christian unity and apologetics are harmonious and complementary, not in contradiction.

Evidence That Demands a Verdict, Josh McDowell (1972)

This is one book that atheists and agnostics love to hate (and also some Christian apologists or apologist-bashers who mock it because it is introductory in nature). But an introduction is just that; one shouldn’t expect more from something than what it purports to be. Everyone has to start somewhere, so I find such attitudes rather condescending and unappreciative.

As it turned out, this book (which I read in 1981) almost singlehandedly provoked an explosion of interest on my part in historical apologetics. Previously I had read only the more philosophical style of apologetics of C. S. Lewis and Francis Schaeffer in 1980 when I was attending Inter-Varsity in college: Wayne State University in Detroit.

Thus, this work profoundly influenced what turned out to be my career. After I read this, I knew what I wanted to do with my life. Before that time, I didn’t, at age 23 and with a relatively worthless (both ideas- and job-wise) degree in sociology nearly completed. 15 years later, I completed my first book of Catholic apologetics, entitled A Biblical Defense of Catholicism.

It was originally modeled (especially in its early version, which compiled a lot of other peoples’ apologetics) after McDowell and also James Cardinal Gibbons‘ book, Faith of Our Fathers. It was intended to provide “biblical evidence for Catholicism” (the name for my website, begun in 1997), in the same way that McDowell had marshaled historic evidence on behalf of Christianity in general, because people think the Bible is opposed to Catholicism, the way they often think that history disproves Christianity itself.

The Gravedigger Files, Os Guinness (1983)

In the vein of Lewis’s wonderful Screwtape Letters, this book by a brilliant evangelical thinker takes the concept of that book one step further by applying a searing analysis to various pitfalls and shortcomings in modern Christianity, from a profoundly Christian and historically long-sighted sociological perspective (influenced a lot by the well-known Lutheran sociologist Peter Berger). When I read this in the early 80s I was already involved in cult research and apologetics and street apologetics.

In 1982 I had written an extensive critique of the “name-it-claim-it, hyper-faith / God always heals movement in charismatic circles (now on my website). I had also majored in sociology in college, so I could relate to the analysis. But the courses I took were thoroughly secular. Needless to say, Christian sociology is infinitely more thought-provoking and explanatory (not to mention, interesting) than the secular variety.

The Spirit of Catholicism, Karl Adam (1928) [available to read online]

This is the best introduction to Catholicism, in my opinion, if one is looking for a treatment of wide scope and vision (also the assessment of Lutheran-then-Orthodox historian Jaroslav Pelikan). It draws you in and doesn’t let you go. It’s irresistible. I doubt that an anti-Catholic would allow himself to be thus enraptured, but for someone with an open mind on the subject, this book will provide a sense of the majesty and profundity of the Catholic Church’s teaching.

It played a key role early in my journey towards the Church in 1990. I described it in my conversion story in Surprised by Truth as “a book too extraordinary to summarize adequately. It is, I believe, a nearly perfect book about Catholicism as a worldview and a way of life, especially for a person acquainted with basic Catholic theology.”

Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine, by Blessed John Henry Cardinal Newman (1845) [available to read online]

This is the book which put me over the edge and convinced me to become a Catholic. It is widely considered the leading treatment on the subject of development of doctrine (my favorite area of theology, and a large emphasis in my apologetics), particularly in its Catholic application or interpretation. I wrote about this book, too, in my published conversion story:

This book demolished the whole schema of Church history which I had constructed. I thought, typically, that early Christianity was Protestant and that Catholicism was a later corruption (although I placed the collapse in the late Middle Ages rather than the usual time of Constantine in the fourth century).

Martin Luther, so I reckoned, had discovered in Sola Scriptura the means to scrape the accumulated Catholic barnacles off of the original lean and clean Christian “ship.” Newman, in contrast, exploded the notion of a barnacle-free ship. Ships always got barnacles. The real question was whether the ship would arrive at its destination. Tradition, for Newman, was like a rudder and steering wheel, and was absolutely necessary for guidance and direction. Newman brilliantly demonstrated the characteristics of true developments, as opposed to corruptions, within the visible and historically continuous Church instituted by Christ. I found myself unable and unwilling to refute his reasoning, and a crucial piece of the puzzle had been put into place — Tradition was now plausible and self-evident to me.

In another paper recounting my conversion from a more technical theological / historical perspective, I wrote, following Newman’s analogical reasoning:

One need not posit an absolute break of continuity in order to equate the present Catholic Church with the “Church” of the early centuries. One need only understand the true nature of development, whereby doctrines can grow in the sense that they are more clearly understood, and more deeply and thoroughly explicated, while not undergoing any essential transformation. But Protestantism requires a radical change of principle, and hence, fails the test of what constitutes a true development, in Newman’s analysis. Besides, corruption can just as easily consist of subtraction as addition. Corruption entails a departure from normalcy and precedent.

Furthermore, it is instructive to realize that what we now consider orthodox in early Christianity, is simply the position of the Roman apostolic see, which was proven right again and again on this score, far beyond coincidence, given the multiplicity of heretical sects in the early centuries, and the thousands of competing Christian denominations today.

Honorable mention: G. K. Chesterton: Orthodoxy (written, incidentally, in 1908: 14 years before GKC’s conversion to Catholicism), Louis Bouyer: The Spirit and Forms of Protestantism, and Thomas Howard: Evangelical is Not Enough.

***

(originally 7-7-05)

Photo credit: drewplaysdrums (8-20-06) [Pixabay / Pixabay License]

***