I wrote my post, No, Pope Francis Did Not Deny Transubstantiation (Phenomenological Language in Holy Scripture and in the Addresses of Pope Francis) in response to the arguments of Novus Ordo Watch, a sedevacantist venue (i.e., one that denies that there is presently a pope; and they usually believe that Ven. Pope Pius XII was the last valid one). They have now counter-replied with On Francis’ Denial of Transubstantiation: A Rejoinder to Dave Armstrong (7-1-19). The words of this article (written by who knows who) will be in blue.

*****

I made various arguments in my paper, which were fairly summarized as follows:

- Francis has affirmed his belief in Transubstantiation on other occasions

- By talking about Jesus becoming bread or being enclosed in bread, Francis is using “phenomenological language”

- The Bible itself uses the term “bread” to refer to the Eucharist

- There are instances of the Church Fathers themselves using the term “bread” in this way

- Popes have referred to the Eucharist as the “Bread of Angels”

I’m saved a lot of trouble, effort, and time, because a cynical, rationalizing tactic was used that has also been utilized by pope-bashers Phil Lawler and Taylor Marshall. It makes much of rational discussion about Pope Francis literally impossible, because it is tin foil hat conspiratorial and utterly subjective in nature:

[W]e can assume that in over six years, Francis probably has taught Transubstantiation explicitly at some point. But even if he did, this in no wise proves that he did not teach heresy during this year’s Corpus Christi sermon. It only proves that he is happy to teach one thing at one time and another thing at another time, precisely as innovators have done for hundreds of years in order to poison souls in the most clever and effective way possible.

In 1794, Pope Pius VI condemned this very tactic, which he had seen used in the robber synod of Pistoia, which was actually a theological prototype of the Second Vatican Council . . .

[much later in his article] Even if Francis has affirmed Transubstantiation somewhere, this proves only that he is content to preach at times orthodoxy and at other times heresy, to the greater confusion of the people and to allow himself plausible deniability for a more effective dissemination of heresy; this is consistent with the approach of past heretics condemned by the Church

Okay; I won’t spend much time with this, given this “move” by our ecclesiologically confused friends. This and other nitpicky, hyper-rationalistic / postmodernist, wooden literalist elements in other portions of the reply lead me to decide to simply deal with the biblical arguments. That was the heart of my paper anyway, and by far of the most interest to me (me being a dedicated student of the Bible these past forty-two years).

The Douay-Rheims translation is used, rather than the RSV of my paper. That’s fine; we’ll play along. I utilized Douay-Rheims heavily in my own New Testament “selection” (I was editor only, not translator): Victorian King James Version of the New Testament: A “Selection” for Lovers of Elizabethan and Victorian Literature.

This is the bread which cometh down from heaven; that if any man eat of it, he may not die. I am the living bread which came down from heaven. … As the living Father hath sent me, and I live by the Father; so he that eateth me, the same also shall live by me. (Jn 6:50-51,58)

And whilst they were at supper, Jesus took bread, and blessed, and broke: and gave to his disciples, and said: Take ye, and eat. This is my body. (Mt 26:26)

And whilst they were eating, Jesus took bread; and blessing, broke, and gave to them, and said: Take ye. This is my body. (Mk 14:22)

And taking bread, he gave thanks, and brake; and gave to them, saying: This is my body, which is given for you. Do this for a commemoration of me. (Lk 22:19)

The chalice of benediction, which we bless, is it not the communion of the blood of Christ? And the bread, which we break, is it not the partaking of the body of the Lord? For we, being many, are one bread, one body, all that partake of one bread. (1 Cor 10:16-17)

For I have received of the Lord that which also I delivered unto you, that the Lord Jesus, the same night in which he was betrayed, took bread, and giving thanks, broke, and said: Take ye, and eat: this is my body, which shall be delivered for you: this do for the commemoration of me. In like manner also the chalice, after he had supped, saying: This chalice is the new testament in my blood: this do ye, as often as you shall drink, for the commemoration of me. For as often as you shall eat this bread, and drink the chalice, you shall shew the death of the Lord, until he come. Therefore whosoever shall eat this bread, or drink the chalice of the Lord unworthily, shall be guilty of the body and of the blood of the Lord. But let a man prove himself: and so let him eat of that bread, and drink of the chalice. For he that eateth and drinketh unworthily, eateth and drinketh judgment to himself, not discerning the body of the Lord. (1 Cor 11:23-29)

Before we answer, we’ll go ahead and make Armstrong’s objection even stronger, for he missed something important: Even the traditional Roman rite of Mass itself uses the term “bread” to refer to the Holy Eucharist after the consecration has taken place:

Mindful, therefore, Lord, we, Thy servants, as also Thy holy people, of the same Christ, Your Son, our Lord, remember His blessed Passion, and also of His Resurrection from the dead, and finally of His glorious Ascension into heaven, offer unto Thy most excellent Majesty of Thine Own gifts, bestowed upon us, a pure Host (Victim), a holy Host, an unspotted Host, the holy Bread of eternal life [Panem sanctum vitae aeternae] and the chalice of everlasting salvation.

(“Unde et Memores”, Latin-English Missal, TraditionalCatholic.net; underlining added.)

In addition, just before the priest administers Holy Communion to himself, he prays: “I will take the Bread of heaven [Panem coelestem], and will call upon the Name of the Lord.” And in the liturgical rite of Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament, the priest chants at the conclusion of the hymn Tantum Ergo: “Thou hast given them bread from heaven” (Panem de coelo praestitisti eis).

Excellent! Thanks! Mine was a biblical argument and not a liturgical one, but this is good.

In the first passage cited, Jn 6:50-51,58, Christ Jesus refers to Himself as the Living Bread come down from Heaven. His use of the word “bread” there is obviously metaphorical, for He is certainly not literal bread, nor did He appear to be bread, either, so one cannot claim He was using phenomenological language.

If we look attentively at the context of John 6, we see that Christ begins His Bread of Life discourse after the Jews challenge Him to work an even greater miracle than the multiplication of the loaves to feed the five thousand: “They said therefore to him: What sign therefore dost thou shew, that we may see, and may believe thee? What dost thou work? Our fathers did eat manna in the desert, as it is written: He gave them bread from heaven to eat” (Jn 6:30-31).

The phrase “bread from heaven” appears in Ps 77:24 in reference to the miraculous manna of Moses (cf. Ex 16:11-15). Our Lord picks up this phrase and applies it to Himself — not as though He were bread in a literal sense but in a metaphorical sense, for He would give His very literal Body and Blood to be consumed by His disciples as the true heavenly food, and that is “bread” much greater than that given by Moses! Hence He says:

I am the bread of life. Your fathers did eat manna in the desert, and are dead. This is the bread which cometh down from heaven; that if any man eat of it, he may not die. I am the living bread which came down from heaven. If any man eat of this bread, he shall live for ever; and the bread that I will give, is my flesh, for the life of the world.

(Jn 6:48-52)

Therefore, unless Armstrong wants to argue that Francis spoke metaphorically, he cannot invoke John 6 in his defense.

John 6 is metaphorical in the beginning sections of what became a eucharistic discourse. All agree on that. Even Catholics and sedevacantists. But then it gets more and more literal and graphically so as He continues. This is what caused some of His disciples to split (6:60-67). They weren’t objecting to a simple pastoral metaphor. They were thinking cannibalism.

John 6:48-52 is where the discourse starts to get explicitly eucharistic. Up till then Jesus talked about (in RSV) belief in Him (6:35-36, 40, 47), coming to Him (6:37, 44-45), and seeing the Son (6:40). Now the fascinating discourse switches or transitions into a “eucharistic mode” and Jesus refers to eating of the bread He is referring to, and living forever as a result (6:50-51), and He defines the bread specifically as “my flesh” (6:51).

That can’t possibly be merely metaphorical at that point (which is precisely why I cited John 6:50-51, 58), because it’s now His flesh, which is eaten, which brings about eternal life and avoidance of eternal damnation, and is given “for the life of the world” (all of that just in 6:50-51). Thus, it has to be literal, because what saves us and gives us eternal life is not just Jesus’ death for us, but also Jesus in the Holy Eucharist: all quite literal things indeed. Otherwise, why mention eating (when He hadn’t up till then)? And we know that He gets even more graphically eucharistic in the rest of His address.

John 6:58 is completely passed over in terms of commentary. In the Douay version used here, it reads “As the living Father hath sent me, and I live by the Father; so he that eateth me, the same also shall live by me.” That doesn’t mention bread, used as a synonym for the Body of Christ, but it does in the RSV: “This is the bread which came down from heaven, not such as the fathers ate and died; he who eats this bread will live for ever.” This is after four verses (6:54-57) — in both versions — where Jesus repeats over and over about eating His Body and drinking His Blood.

But for some reason Douay doesn’t mention “bread” in verse 58. I see now that the verse numbers are slightly different in Douay-Rheims. It is John 6:59 in that version that is the same one as 6:58 in most versions. Here is is, in Douay:

This is the bread that came down from heaven. Not as your fathers did eat manna, and are dead. He that eateth this bread, shall live for ever.

Jesus ties it all together. He starts with the “bread from heaven” metaphor: an analogy to the manna of the Old Testament (6:31-32, 49-50). Then He transitions into making this word-picture explicitly eucharistic. He defines “this bread” as “my flesh” in 6:51. Then He goes back again to the manna analogy in 6:58 (6:59 in Douay). And this gets back to the issue with Pope Francis. Jesus still calls the eucharistic element of what was once bread and is now His Body, “bread”: just as Pope Francis did. “He that eateth this bread, shall live for ever.” Obviously, it’s not literal bread that gives eternal life, but consecrated bread; i.e., His Body (transubstantiation).

But Jesus still calls that bread. He refuses to stop saying “bread” when referring to what has been transformed into His body. Why? Phenomenological language . . . He had already done this in 6:50-51, then started talking about flesh and blood, then went back to “bread” to drive home the point that it was the Holy Eucharist that He was talking about.

The manna gave physical life, and now the “bread” that is His flesh gives eternal life. St. Peter uses exactly this same reasoning and progression with regard to baptism: Noah and his family were physically “saved through water” (“saved by water” in Douay) and now baptism regenerates or spiritually saves the baptized:

1 Peter 3:20-21 (RSV) who formerly did not obey, when God’s patience waited in the days of Noah, during the building of the ark, in which a few, that is, eight persons, were saved through water. [21] Baptism, which corresponds to this, now saves you, not as a removal of dirt from the body but as an appeal to God for a clear conscience, through the resurrection of Jesus Christ,

The comparison is not merely metaphorical. The progression is from “physical life” to “eternal life” in both passages. It is eating and being saved from drowning in the Old Testament (to sustain physical life) and partaking of the Eucharist and baptism for the purpose of eternal life.

Conclusion: Jesus referred to His physical eucharistic Body as “bread” six times in John 6:50-5, 58 (6:50-52, 59 in Douay-Rheims). Pope Francis speaks similarly: no problem. If he’s a heretic, so is Jesus. I guess if we can have no pope in sedevacantism, which destroys the doctrine of the indefectibility of the Church and reduces to Orthodox ecclesiology, we can also have a heretical Jesus, Who believes in Lutheran consubstantiation. One thing is as ridiculous and unbiblical and unCatholic as the other.

The second, third, and fourth passages cited (Mt 26:26; Mk 14:22; Lk 22:19) are of questionable relevance since the “bread” our Blessed Lord took into His sacred hands was, at that moment, still unconsecrated. Does Armstrong perhaps mean to argue that the Gospel writer nevertheless also speaks of it being broken and given to the disciples, after Transubstantiation has already occurred, without pointing out separately that the bread is then no longer bread?

Yes. Simple logic and grammar. In all three passages, Jesus “took bread” and then “gave it [bread] to” the disciples and then defined it as “my body.” In order to be literal language and not phenomenological, “gave it” would have to read, “gave his body”. But that’s not what the texts say: written by three evangelists out of four. They call the consecrated bread “bread” after consecration. So they are heretics, too, if we interpret literally and prima facie. But if we understand how language works, it is not heretical.

That would be Armstrong scraping the bottom of his apologetical barrel. If that kind of hairsplitting is what he wishes to hang his entire defense of Bergoglio on, he needs only to say so, and we can then fight that one out in a follow-up post.

This is called obfuscation. It’s not my “entire defense” (how melodramatic!); it’s consistent eucharistic phenomenological language in Holy Scripture with regard to the Holy Eucharist. The cumulative argument is so strong that even my opponent is forced to almost totally concede my argument regarding the two Pauline passages below, because one (actually two) of the old commentaries that he trusts did so. Surprise!

The fifth passage cited is 1 Cor 10:16-17, in which St. Paul refers to the Holy Eucharist as “the bread, which we break” and the “one bread” of which all partake. Is this an instance of phenomenological language?

It might be — the commentaries from Catholic Scripture scholars are not all in agreement. For example, Fr. George Leo Haydock notes that St. Paul speaks in this manner “because of the outward appearance of bread” (source), which would support a phenomenological understanding. On the other hand, Fr. Cornelius à Lapide sees in the term “bread” an idiomatic expression proper to Hebrew, called a “Hebraism”, which would be closer to a metaphor:

I reply that bread, by a Hebraism, stands for any food (2 Kings ii. 22 [sic— presumably means xii. 21 here]). So Christ is called manna (S. John vi. 31), and bread (Ibid. vi. 41). The reason is that bread is the common and necessary food of all. Moreover, S. Paul does not say “bread” simply, but “the bread which we break,” i.e., the Eucharistic or transubstantiated bread, which is the body of Christ, and yet retains the species and power of bread. In this agree all the Fathers and orthodox doctors. Christ, on other occasions as well as in the Last Supper, is said to have broken and distributed the bread, according to the Hebrew custom by which the head of the house was wont to break the bread and divide the food among the guests sitting at table. For the Easterns did not have loaves shaped like ours, which need a knife to cut them up, but they used to make their bread into wide and thin cakes…. Hence “to break bread” signifies in Scripture “to feast,” and breaking bread signifies any feast, dinner, or meal. In the New Testament it is appropriated to the Eucharist; therefore “to break bread” is a sacramental and ecclesiastical term. Hence S. Paul calls here the Eucharist “the bread which we break,” meaning the species of the body of Christ which we break and consume in the sacrament.

(The Great Commentary of Cornelius à Lapide: I Corinthians, trans. and ed. by W. F. Cobb [Edinburgh: John Grant, 1908], pp. 242-243; underlining added.)

I don’t see how Cornelius à Lapide is any different from Haydock. St. Paul describing the “one bread” also as “the bread which we break” is still calling it (Him) “bread” and simply adding what was done to it (Him). This doesn’t allow my opponent to cite a “technicality” and thus squirm out of his dilemma. It’s not that easy! Lapide himself uses the term, “transubstantiated bread.” I think here is where the mystery opponent’s counter-argument regarding Scripture completely breaks down, and so he tries to hide that fact by playing with words and saying it is “closer to a metaphor.” Nice try; no cigar.

The old commentaries didn’t support his case; they upheld mine. The three evangelists were utterly ignored. And Pope Francis used the phrase, “bread broken and shared” which I see as the identical notion as Lapide’s “Christ . . . is said to have broken and distributed the bread.” Where’s the beef? Now ol’ Lapide is a Lutheran heretic, too? But if the pope is, how is Lapide not? How is St. Paul not, for that matter? How the mighty have fallen . . .

Lapide then refers the reader to his commentary on 1 Cor 11:24, which takes us to the sixth passage cited by Armstrong (1 Cor 11:23-29). Lapide says:

Hence there is no foundation for the argument of Calvin, who says that all these words “took,” “blessed,” “brake,” “gave,” refer to bread only, and that therefore it was bread that the Apostles took and ate, not the body of Christ. My answer is that these words refer to the bread, not as it remained bread, but as it was changed into the body of Christ while being given, by the force of the words of consecration used by Christ. In the same way Christ might have said at Cana of Galilee, “Take, drink; this is wine,” if He had wished by these words to change the water into wine. So we are in the habit of saying, Herod imprisoned, slew, buried, or permitted to be buried, S. John, when what he buried was not what he imprisoned: he imprisoned a man; he buried a corpse. Like this, and consequently just as common, is this way of speaking about the Eucharist, which is used by the Evanglists and S. Paul.

(Great Commentary: I Corinthians, p. 272; underlining added.)

We can understand this final passage too, then, as either using the word “bread” in a phenomenological sense or else as a Hebraism meaning “food”.

This is a rather spectacular concession as well. Lapide dramatically makes my case. I’m delighted to see that it has now become even stronger and more unanswerable than it was.

All this leads us to the following conclusion: Out of the six passages brought up by Armstrong to substantiate the claim that the use of phenomenological language has biblical precedent, at most two of them actually do so, whereas the other four do not.

Nonsense. He ignored one of the verses in John 6 that formed part of my argument, and inadequately exegeted the other two. I argued rings around him in analyzing John 6. He dismissed the three passages from the Synoptic Gospels with no actual argument and a silly swipe at me: to give the illusory appearance of strength. And now he has to concede the two Pauline passages and then go on to pretend that he actually prevailed in this argument. What a joke! It’s quite amusing to watch a “bad lawyer” with no case in action: spinning like a top and mightily obfuscating, in order to vainly avoid total embarrassment. He gave it the old college try, but failed. You can’t make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear!

Most of the rest of Mystery Man’s analysis is devoted to essentially denigrating the inspired revelation of Scripture as unacceptably outdated in its expression of language:

The idea of returning to the language of Scripture ultimately implies that it doesn’t matter what the Church has defined, or what terminology she has sanctioned or forbidden, because we can never go wrong using the language Christ Himself or the biblical writers used. What an insult to Christ and His Church!

This is flat-out astonishing: virtually a caricature of how Protestants view Catholics: being hostile to the Bible. I won’t even give such a ludicrous so-called “argument” the dignity of a response. Scripture remains inspired revelation and eternally relevant. Sure, doctrines and theology develop (development of doctrine is my favorite theological topic, and what made me a Catholic), and we have to understand that Scripture came about early in that progression, but it doesn’t therefore become relegated to secondary status. The renewed emphasis on Holy Scripture is an excellent and necessary trend, and it didn’t start with Vatican II; more like Pope Leo XIII’s 1893 encyclical, Providentissimus Deus (On the Study of Holy Scripture). In it he stated:

4. And it is this peculiar and singular power of Holy Scripture, arising from the inspiration of the Holy Ghost, which gives authority to the sacred orator, fills him with apostolic liberty of speech, and communicates force and power to his eloquence. For those who infuse into their efforts the spirit and strength of the Word of God, speak “not in word only but in power also, and in the Holy Ghost, and in much fulness.”(12) Hence those preachers are foolish and improvident who, in speaking of religion and proclaiming the things of God, use no words but those of human science and human prudence, trusting to their own reasonings rather than to those of God. Their discourses may be brilliant and fine, but they must be feeble and they must be cold, for they are without the fire of the utterance of God(13) and they must fall far short of that mighty power which the speech of God possesses: “for the Word of God is living and effectual, and more piercing than any two-edged sword; and reaching unto the division of the soul and the spirit.”(14) But, indeed, all those who have a right to speak are agreed that there is in the Holy Scripture an eloquence that is wonderfully varied and rich, and worthy of great themes. This St. Augustine thoroughly understood and has abundantly set forth.(15) This also is confirmed by the best preachers of all ages, who have gratefully acknowledged that they owed their repute chiefly to the assiduous use of the Bible, and to devout meditation on its pages.

5. The Holy Fathers well knew all this by practical experience, and they never cease to extol the sacred Scripture and its fruits. In innumerable passages of their writings we find them applying to it such phrases as “an inexhaustible treasury of heavenly doctrine,”(16) or “an overflowing fountain of salvation,”(17) or putting it before us as fertile pastures and beautiful gardens in which the flock of the Lord is marvellously refreshed and delighted.(18) Let us listen to the words of St. Jerome, in his Epistle to Nepotian: “Often read the divine Scriptures; yea, let holy reading be always in thy hand; study that which thou thyself must preach. . . Let the speech of the priest be ever seasoned with Scriptural reading.”(19) St. Gregory the Great, than whom no one has more admirably described the pastoral office, writes in the same sense: “Those,” he says, “who are zealous in the work of preaching must never cease the study of the written word of God.”(20) St. Augustine, however, warns us that “vainly does the preacher utter the Word of God exteriorly unless he listens to it interiorly;”(21) and St. Gregory instructs sacred orators “first to find in Holy Scripture the knowledge of themselves, and then to carry it to others, lest in reproving others they forget themselves.”(22) . . .

7. And here, in order to strengthen Our teaching and Our exhortations, it is well to recall how, from the beginning of Christianity, all who have been renowned for holiness of life and sacred learning have given their deep and constant attention to Holy Scripture. . . . [mentions a host of Fathers and Doctors of the Church] . . . The valuable work of the scholastics in Holy Scripture is seen in their theological treatises and in their Scripture commentaries; and in this respect the greatest name among them all is St. Thomas of Aquin. . . .

16. Most desirable is it, and most essential, that the whole teaching of Theology should be pervaded and animated by the use of the divine Word of God. This is what the Fathers and the greatest theologians of all ages have desired and reduced to practice. It was chiefly out of the Sacred Writings that they endeavoured to proclaim and establish the Articles of Faith and the truths therewith connected, and it was in them, together with divine Tradition, that they found the refutation of heretical error, and the reasonableness, the true meaning, and the mutual relation of the truths of Catholicism. Nor will any one wonder at this who considers that the Sacred Books hold such an eminent position among the sources of revelation that without their assiduous study and use, Theology cannot be placed on its true footing, or treated as its dignity demands. For although it is right and proper that students in academies and schools should be chiefly exercised in acquiring a scientific knowledge of dogma, by means of reasoning from the Articles of Faith to their consequences, according to the rules of approved and sound philosophy – nevertheless the judicious and instructed theologian will by no means pass by that method of doctrinal demonstration which draws its proof from the authority of the Bible; “for (Theology) does not receive her first principles from any other science, but immediately from God by revelation. And, therefore, she does not receive of other sciences as from a superior, but uses them as her inferiors or handmaids.”(42) It is this view of doctrinal teaching which is laid down and recommended by the prince of theologians, St. Thomas of Aquin;(43) who, moreover, shows – such being the essential character of Christian Theology – how she can defend her own principles against attack: “If the adversary,” he says, “do but grant any portion of the divine revelation, we have an argument against him; thus, against a heretic we can employ Scripture authority, and against those who deny one article, we can use another. But if our opponent reject divine revelation entirely, there is then no way left to prove the Article of Faith by reasoning; we can only solve the difficulties which are raised against them.”(44)’ Care must be taken, then, that beginners approach the study of the Bible well prepared and furnished; otherwise, just hopes will be frustrated, or, perchance, what is worse, they will unthinkingly risk the danger of error, falling an easy prey to the sophisms and laboured erudition of the Rationalists. The best preparation will be a conscientious application to philosophy and theology under the guidance of St. Thomas of Aquin, and a thorough training therein – as We ourselves have elsewhere pointed out and directed. By this means, both in Biblical studies and in that part of Theology which is called positive, they will pursue the right path and make satisfactory progress.

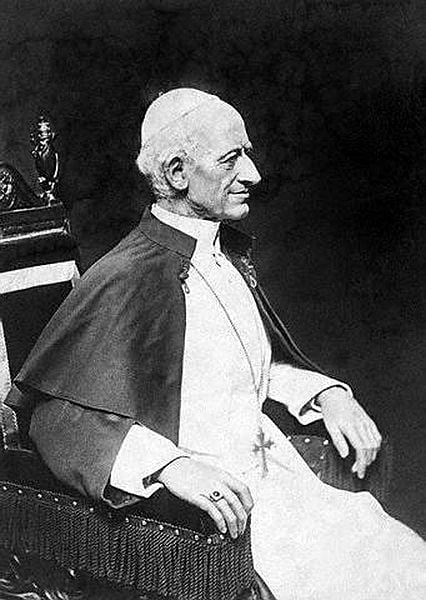

I’m delighted to end with this fabulous teaching from a pope that even the Protestant- and liberal-influenced, hyper-rationalist sedevacantists can accept: the great Pope Leo XIII: who loved my hero Cardinal Newman (to be proclaimed a saint in now less than four months) and made him a Cardinal.

***

Photo credit: Pope Leo XIII, circa 1903 [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]