This is a reply to Bishop “Dr.” [???] James White’s article, “Truths of the Bible or Untruths of Roman Tradition?: James White Responds to Tim Staples’ Article, “How to Explain the Eucharist” in the September, 1997 issue of Catholic Digest“ (1 March 2000).

See my Introduction to what will be a very long series (and the other installments). Words of James White will be in blue.

*****

Catholic apologists know the situation well. The Evangelical Christian has his Bible and is making waves at a family reunion. It’s a common situation since 1) Evangelicals are evangelical; that is, they share their faith, and few Catholics even view their faith as something that is “sharable”; and 2) evangelicals love and study the Bible, believe it, and seek to share its message with those around them. So the new breed of Catholic apologists have to find ways to get their followers into the “game” so to speak.

This is true (to our shame). It’s why I write articles like these:

“Why Don’t Catholics Read the Bible?” [6-26-02]

Bibles & Catholics, Sunday School?, Memorization, Etc. [9-25-08]

In the September, 1997 issue of Catholic Digest, Tim Staples, a former member of the Assemblies of God, attempts to provide Catholics with a way of replying in a “biblical” fashion so as to answer the question, “Why Catholics believe in the Real Presence of Christ.” In this little article, Staples provides “practical advice” on how to shut the mouth of the Bible-believer so as to promote the Roman Catholic position. But let’s look closely at what he says.

And let’s also look closely at the falsehoods and fallacies in Bishop White’s replies.

[J]ust because Jesus uses the terminology of flesh and blood [in John 6] doesn’t mean we are justified in forcing such terms into a wooden literality. Jesus used symbols to convey greater truths, and if the context of the passage indicates this is what He is doing, we have no reason at all to force Him into some absurd literality. And that is exactly what we have here. Those who walked away were the grumbling Jews who forsook Him and did not understand His message. Looking to them for guidance to the meaning of Jesus’ words is probably a very, very bad idea.

I have examined in great depth the claim that Jesus was only speaking symbolically in John 6, and show why — all things considered — this view can’t hold up under scrutiny:

*

“He that comes unto Me: this is the same as when He says, And he that believes on Me: and what He meant by, shall never hunger, the same we are to understand by, shall never thirst. By both is signified that eternal fulness, where is no lack.”

There is no literality in Augustine’s understanding. Note his further comments on the passage:

Let them then who eat, eat on, and them that drink, drink; let them hunger and thirst; eat Life, drink Life. That eating, is to be refreshed; but you are in such wise refreshed, as that that whereby you are refreshed, does not fail. That drinking, what is it but to live? Eat Life, drink Life; you will have life, and the Life is Entire. But then this shall be, that is, the Body and Blood of Christ shall be each man’s Life; if what is taken in the Sacrament visibly is in truth itself eaten spiritually, drunk spiritually. For we have heard the Lord Himself saying, It is the Spirit that gives life, but the flesh profits nothing. The words that I have spoken to you are Spirit and Life.”

Here are a few more just for the fun of it:

Augustine (Faustus 6.5): “while we consider it no longer a duty to offer sacrifices, we recognize sacrifices as part of the mysteries of Revelation, by which the things prophesied were foreshadowed. For they were our examples, and in many and various ways they all pointed to the one sacrifice which we now commemorate. Now that this sacrifice has been revealed, and has been offered in due time, sacrifice is no longer binding as an act of worship, while it retains its symbolical authority.”

Augustine (Faustus 20.18, 20): “The Hebrews, again, in their animal sacrifices, which they offered to God in many varied forms, suitably to the significance of the institution, typified the sacrifice offered by Christ. This sacrifice is also commemorated by Christians, in the sacred offering and participation of the body and blood of Christ. . . . Before the coming of Christ, the flesh and blood of this sacrifice were foreshadowed in the animals slain; in the passion of Christ the types were fulfilled by the true sacrifice; after the ascension of Christ, this sacrifice is commemorated in the sacrament.

Where is the literality? It is not there, which is why there were debates a thousand years after Christ concerning this very issue: and Augustine was one of the chief Fathers cited by those who opposed the absurdly literal interpretation that lead to transubstantiation.

In a paper I wrote detailing my odyssey to the Catholic Church, I recounted my own use of the approach I am now critiquing:

I claimed that St. Augustine . . . adopted a symbolic view of the Eucharist. I based this on his oft-stated notion of the sacrament as symbol or sign. I failed to realize, however, that I was arbitrarily creating a false, logically unnecessary dichotomy between the sign and the reality of the Eucharist, for St. Augustine — when all his remarks on the subject are taken into account — clearly accepted the Real Presence. The Eucharist — for Augustine, and objectively speaking — is both sign and reality. There simply is no contradiction.

A cursory glance at Scripture confirms this general principle. For instance, Jesus refers to the sign of Jonah, comparing the prophet Jonah’s three days and nights in the belly of the fish to His own burial in the earth (Mt 12:38-40). In this case, both events, although described as signs, were quite real indeed. Jesus also uses the terminology of sign in connection with His Second Coming (Mt 24:30-31), which is believed by all Christians to be a literal event, and not symbolic only.

Now, on to St. Augustine’s statements which very strongly support the opinion that He held to the Real Presence in the Eucharist:

IV. From Ludwig Ott (Fundamentals of Catholic Dogma, translated by Patrick Lynch, edited by James C. Bastible, Rockford, Illinois: TAN Books, 1974 [orig. 1952 in German]):

1) The bread which you see on the altar is, sanctified by the word of God, the body of Christ; that chalice, or rather what is contained in the chalice, is, sanctified by the word of God, the blood of Christ. (Sermo 227; on p. 377)

2) Christ bore Himself in His hands, when He offered His body saying: “this is my body.” (Enarr. in Ps. 33 Sermo 1, 10; on p. 377)

3) Nobody eats this flesh without previously adoring it. (Enarr. in Ps. 98, 9; on p. 387)

4) Referring to the sacrifice of Melchizedek (Gen 14:18 ff.):

The sacrifice appeared for the first time there which is now offered to God by Christians throughout the whole world. (City of God, 16, 22; on p. 403)

Ott cites other references or beliefs of St. Augustine:

A) Interpretation of Jn 6:51b-58 as referring to the Eucharist (p. 374)

B) Christ was both the sacrificing Priest and the sacrificial Gift in one Person (City of God, 10, 20; Ep. cf. 98, 9; on p. 406)

C) The sacrifice of the Mass is that foretold by Malachi [1:10-11] (Tract. adv. Jud. 9, 13; on p. 406)

D) The Mass is a propitiatory sacrifice bringing about remission of sins and the conferring of supernatural gifts (De cura pro mortuis fier. 1, 3; 18, 22; Enchir. 110; on p. 413)

V. William A. Jurgens, The Faith of the Early Fathers, vol. 3, edited and translated by Jurgens, Collegeville, Minnesota: The Liturgical Press, 1979:

5) He took flesh from the flesh of Mary . . . and gave us the same flesh to be eaten unto salvation . . . we do sin by not adoring. (Explanations of the Psalms , 98, 9; on p. 20)

6) Not all bread, but only that which receives the blessing of Christ, becomes Christ’s body. (Sermons, 234, 2; on p. 31)

7) What you see is the bread and the chalice . . . But what your faith obliges you to accept is that the bread is the Body of Christ and the chalice the Blood of Christ. (Sermons, 272; on p. 32)

8) Christ is both the priest, offering Himself, and Himself the Victim. He willed that the sacramental sign of this should be the daily sacrifice of the Church. (City of God, 10, 20; on p. 99)

9) Not only is no one forbidden to take as food the Blood of this Sacrifice, rather, all who wish to possess life are exhorted to drink thereof. (Questions of the Hepateuch, 3, 57; on p. 134)

VI. Hugh Pope, St. Augustine of Hippo, Garden City, New York: Doubleday Image, 1961 (orig. 1937):

10) The Sacrifice of our times is the Body and Blood of the Priest Himself . . . Recognize then in the Bread what hung upon the tree; in the chalice what flowed from His side. (Sermo iii. 1-2; on p. 62)

11) The Blood they had previously shed they afterwards drank. (Mai 26, 2; 86, 3; on p. 64)

12) Eat Christ, then; though eaten He yet lives, for when slain He rose from the dead. Nor do we divide Him into parts when we eat Him: though indeed this is done in the Sacrament, as the faithful well know when they eat the Flesh of Christ, for each receives his part, hence are those parts called graces. Yet though thus eaten in parts He remains whole and entire; eaten in parts in the Sacrament, He remains whole and entire in Heaven. (Mai 129, 1; cf. Sermon 131; on p. 65)

13) Out of hatred of Christ the crowd there shed Cyprian’s blood, but today a reverential multitude gathers to drink the Blood of Christ . . . this altar . . . whereon a Sacrifice is offered to God . . . (Sermo 310, 2; cf. City of God, 8, 27, 1; on p. 65)

14) He took into His hands what the faithful understand; He in some sort Bore Himself when He said: This is My Body. (Enarr . 1, 10 on Ps. 33; on p. 65)

15) The very first heresy was formulated when men said: “this saying is hard and who can bear it [Jn 6:60]?” ( Enarr . 1, 23 on Ps. 54; on p. 66)

16) Thou art the Priest, Thou the Victim, Thou the Offerer, Thou the Offering. (Enarr . 1, 6 on Ps. 44; on p. 66)

17) Take, then, and eat the Body of Christ . . . You have read that, or at least heard it read, in the Gospels, but you were unaware that the Son of God was that Eucharist. (Denis , 3, 3; on p. 66)

18) The entire Church observes the tradition delivered to us by the Fathers, namely, that for those who have died in the fellowship of the Body and Blood of Christ, prayer should be offered when they are commemorated at the actual Sacrifice in its proper place, and that we should call to mind that for them, too, that Sacrifice is offered. (Sermo, 172, 2; 173, 1; De Cura pro mortuis, 6; De Anima et ejus Origine, 2, 21; on p. 69)

19) We do pray for the other dead of whom commemoration is made. Nor are the souls of the faithful departed cut off from the Church . . . Were it so, we should not make commemoration of them at the altar of God when we receive the Body of Christ. (Sermo 159,1; cf. 284, 5; 285, 5; 297, 3; City of God, 20, 9, 2; cf. 21,24; 22, 8; on p. 69)

20) It was the will of the Holy Spirit that out of reverence for such a Sacrament the Body of the Lord should enter the mouth of a Christian previous to any other food. (Ep. 54, 8; on p. 71)

Lutheran (later Orthodox) Church historian Jaroslav Pelikan, explains Augustine’s views

It is incorrect, therefore, to attribute to Augustine either a scholastic doctrine of transubstantiation or a Protestant doctrine of symbolism, for he taught neither — or both –– and both were able to cite his authority. (The Emergence of the Catholic Tradition (100-600), Univ. of Chicago Press, 1971, 305, emphasis added)

Pelikan had just given several examples of rather obvious and extreme Eucharistic realism and literalism (many if not all included in my own proofs). The simple fact of the matter is that Augustine speaks in both ways. But we can harmonize them as complementary, not contradictory, because Catholics, like Augustine himself, tend to think in terms of “both/and” rather than the dichotomous “either/or” prevalent in Protestantism. Thus, when some Augustinian symbolic Eucharistic utterance is found, it is seized upon as “proof” that he thereby denied the Real Presence.

It is difficult to conceive of anyone denying that St. Augustine believed in the Real Presence (or the Sacrifice of the Mass) after perusing all of this compelling evidence. His other symbolic utterances have been sufficiently explained and are easily able to be synthesized with the above beliefs. St. Augustine is indeed an “insufficient witness” to Protestant belief in a symbolic, or “dynamic” Eucharist.

Anglican historian J. N. D. Kelly (Early Christian Doctrines, San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1978, 447), summarizes:

- One could multiply texts like these which show Augustine taking for granted the traditional identification of the elements with the sacred body and blood. There can be no doubt that he [Augustine] shared the realism held by almost all of his contemporaries and predecessors.

White cites eminent Protestant historian Philip Schaff, writing about how the Church fathers had both literal and symbolic understandings of the Holy Eucharist. He cites Augustine as in the latter camp. But wait! Schaff also wrote the following:

The doctrine of the sacrament of the Eucharist was not a subject of theological controversy . . . . till the time of Paschasius Radbert, in the ninth century . . .

In general, this period, . . . was already very strongly inclined toward the doctrine of transubstantiation, and toward the Greek and Roman sacrifice of the mass, which are inseparable in so far as a real sacrifice requires the real presence of the victim……

[Augustine] at the same time holds fast the real presence of Christ in the Supper . . . He was also inclined, with the Oriental fathers, to ascribe a saving virtue to the consecrated elements.

Augustine . . . on the other hand, he calls the celebration of the communion ‘verissimum sacrificium’ of the body of Christ. The church, he says, offers (‘immolat’) to God the sacrifice of thanks in the body of Christ. [City of God, 10,20] (History of the Christian Church, vol. 3, A.D. 311-600, revised 5th edition, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans, reprinted in 1974, originally 1910, 492, 500, 507)

Note: Schaff had just for two pages (pp. 498-500) shown how St. Augustine spoke of symbolism in the Eucharist as well, but he honestly admits that the great Father accepted the Real Presence “at the same time.” This is precisely what I would argue. Catholics have a reasonable explanation for the “symbolic” utterances, which are able to be harmonized with the Real Presence, but Protestants, who maintain that Augustine was a Calvinist or Zwingian in his Eucharistic views must ignore the numerous references to an explicit Real Presence in Augustine, and of course this is objectionable scholarship.

It seems historians do not share Tim’s viewpoint, and for good reason. We could cite from Tertullian and Theodoret and many others, . . . Of course, it is easier to make universal claims about history that are inaccurate than it is to provide a meaningful and truthful response.

Two can play that game, and I can and do cite from many Church fathers, as well (see my Fathers of the Church page, “Eucharist and Sacrifice of the Mass” section): showing how they accept the real, substantial presence of Christ in the Eucharist. And as for historians, here’s what five eminent Protestant ones say about patristic views on the Eucharist:

1) Otto W. Heick, A History of Christian Thought, vol. 1, Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1965, 221-222:

- The Post-Apostolic Fathers and . . . almost all the Fathers of the ancient Church . . . impress one with their natural and unconcerned realism. To them the Eucharist was in some sense the body and blood of Christ.

2) Williston Walker, A History of the Christian Church, 3rd edition, revised by Robert T. Handy, New York: Scribners, 1970, 90-91:

- By the middle of the 2nd century, the conception of a real presence of Christ in the Supper was wide-spread . . . The essentials of the ‘Catholic’ view were already at hand by 253.

3) J. D. Douglas, editor, The New International Dictionary of the Christian Church, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan, revised edition, 1978, 245 [a very hostile source!]:

- The Fathers . . . [believed] that the union with Christ given and confirmed in the Supper was as real as that which took place in the incarnation of the Word in human flesh.

4) F. L. Cross and E. A. Livingstone, editors, The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, Oxford Univ. Press, 2nd edition, 1983, 475-476, 1221:

That the Eucharist conveyed to the believer the Body and Blood of Christ was universally accepted from the first . . . Even where the elements were spoken of as ‘symbols’ or ‘antitypes’ there was no intention of denying the reality of the Presence in the gifts . . . In the Patristic period there was remarkably little in the way of controversy on the subject . . . The first controversies on the nature of the Eucharistic Presence date from the earlier Middle Ages. In the 9th century Paschasius Radbertus raised doubts as to the identity of Christ’s Eucharistic Body with His Body in heaven, but won practically no support. Considerably greater stir was provoked in the 11th century by the teaching of Berengar, who opposed the doctrine of the Real Presence. He retracted his opinion, however, before his death in 1088 . . .

It was also widely held from the first that the Eucharist is in some sense a sacrifice, though here again definition was gradual. The suggestion of sacrifice is contained in much of the NT language . . . the words of institution, ‘covenant,’ ‘memorial,’ ‘poured out,’ all have sacrificial associations. In early post-NT times the constant repudiation of carnal sacrifice and emphasis on life and prayer at Christian worship did not hinder the Eucharist from being described as a sacrifice from the first . . .

From early times the Eucharistic offering was called a sacrifice in virtue of its immediate relation to the sacrifice of Christ.

5) Jaroslav Pelikan, The Emergence of the Catholic Tradition (100-600), Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1971, 146-147, 166-168, 170, 236-237:

By the date of the Didache [anywhere from about 60 to 160, depending on the scholar]. . . the application of the term ‘sacrifice’ to the Eucharist seems to have been quite natural, together with the identification of the Christian Eucharist as the ‘pure offering’ commanded in Malachi 1:11 . . .

The Christian liturgies were already using similar language about the offering of the prayers, the gifts, and the lives of the worshipers, and probably also about the offering of the sacrifice of the Mass, so that the sacrificial interpretation of the death of Christ never lacked a liturgical frame of reference . . .

. . . the doctrine of the real presence of the body and blood of Christ in the Eucharist, which did not become the subject of controversy until the ninth century. The definitive and precise formulation of the crucial doctrinal issues concerning the Eucharist had to await that controversy and others that followed even later. This does not mean at all, however, that the church did not yet have a doctrine of the Eucharist; it does mean that the statements of its doctrine must not be sought in polemical and dogmatic treatises devoted to sacramental theology. It means also that the effort to cross-examine the fathers of the second or third century about where they stood in the controversies of the ninth or sixteenth century is both silly and futile . . .

Yet it does seem ‘express and clear’ that no orthodox father of the second or third century of whom we have record declared the presence of the body and blood of Christ in the Eucharist to be no more than symbolic (although Clement and Origen came close to doing so) or specified a process of substantial change by which the presence was effected (although Ignatius and Justin came close to doing so). Within the limits of those excluded extremes was the doctrine of the real presence . . .

The theologians did not have adequate concepts within which to formulate a doctrine of the real presence that evidently was already believed by the church even though it was not yet taught by explicit instruction or confessed by creeds . . .

Liturgical evidence suggests an understanding of the Eucharist as a sacrifice, whose relation to the sacrifices of the Old testament was one of archetype to type, and whose relation to the sacrifice of Calvary was one of ‘re-presentation,’ just as the bread of the Eucharist ‘re-presented’ the body of Christ . . . the doctrine of the person of Christ had to be clarified before there could be concepts that could bear the weight of eucharistic teaching . . .

Theodore [c.350-428] set forth the doctrine of the real presence, and even a theory of sacramental transformation of the elements, in highly explicit language . . . ‘At first it is laid upon the altar as a mere bread and wine mixed with water, but by the coming of the Holy Spirit it is transformed into body and blood, and thus it is changed into the power of a spiritual and immortal nourishment.’ [Hom. catech. 16,36] these and similar passages in Theodore are an indication that the twin ideas of the transformation of the eucharistic elements and the transformation of the communicant were so widely held and so firmly established in the thought and language of the church that everyone had to acknowledge them.

But at this point in debates, White invariably splits, because his presentation has been revealed as bogus and historically dishonest. Once his sophistical schtick is exposed for what it is, he has nothing else to offer. Believe me, I know what I’m talking about, having dealt with this man for now 24 years.

Most don’t carry around notes with quotations from patristic sources so as to be ready for such claims.

That’s right. But an apologist like myself has them at the ready, in my 2500+ articles and 50 books (the result of now 38 years of continual research and writing). And we see how the debate goes once the relevant data is fairly explored.

***

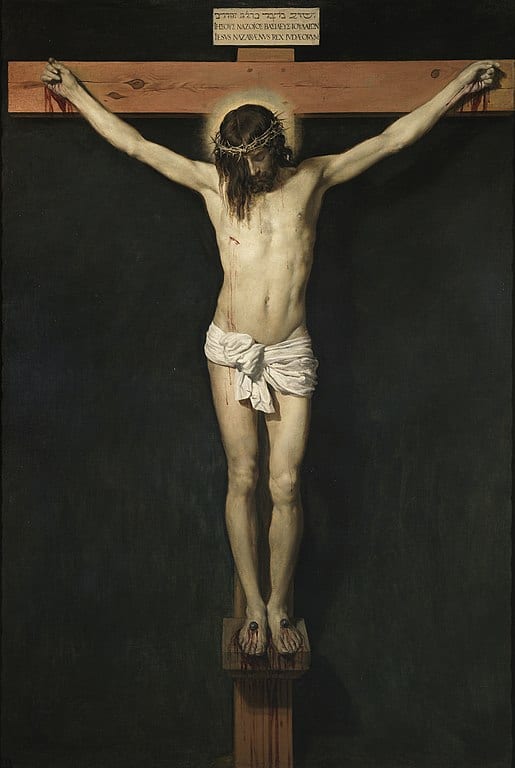

Photo credit: Christ Crucified (c. 1632), by Diego Velázquez (1599-1660) [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

***