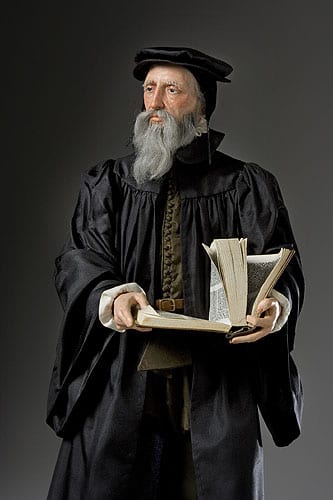

This is an installment of a series of replies (see the Introduction and Master List) to much of Book IV (Of the Holy Catholic Church) — and some portions of Books I-III — of Institutes of the Christian Religion, by early Protestant leader John Calvin (1509-1564). I utilize the public domain translation of Henry Beveridge, dated 1845, from the 1559 edition in Latin; available online. Calvin’s words will be in blue. All biblical citations (in my portions) will be from RSV unless otherwise noted.

Related reading from yours truly:

Biblical Catholic Answers for John Calvin (2010 book: 388 pages)

A Biblical Critique of Calvinism (2012 book: 178 pages)

Biblical Catholic Salvation: “Faith Working Through Love” (2010 book: 187 pages; includes biblical critiques of all five points of “TULIP”)

*****

I, 7:1-2, 5 / 8:10, 12

***

With great insult to the Holy Spirit, it is asked, who can assure us that the Scriptures proceeded from God; who guarantee that they have come down safe and unimpaired to our times; (I, 7:1)

This is not an exegetical issue, but since it has directly to do with the Bible, I shall treat it in this and the next section.

Accuracy of manuscript transmission is indeed an important issue. In order for it to obtain, one must presuppose or accept that those who are transmitting it reverence the source enough to transmit it accurately. Historically, that task fell to monks: many of whom devoted their entire lives to it. This is of paramount importance, and is not mere fodder for Calvin’s tauntings and mockery, as if it were of no importance.

But note how Calvin is treating two different topics in his first and second clauses above. Cleverly, but sophistically, in the first clause, he directly ties in transmission with the notion of divine authorship (second clause), whereas they are two quite distinct matters. Ultimately (and somewhat technically), the Church doesn’t “guarantee” that Holy Scripture is inspired. That is held in faith, by the internal witness of the Holy Spirit. But it does claim some direct responsibility in accurate transmission.

In any event, the Catholic position, rightly understood, is no insult to the Holy Spirit at all, whereas misrepresentation and bearing of false witness about fellow Christians, certainly is such an insult.

who persuade us that this book is to be received with reverence, and that one expunged from the list, did not the Church regulate all these things with certainty? (I, 7:1)

It is historically unarguable that without authoritative Church pronouncements, differences about the canon of Scripture would have persisted, since they did (among equally godly men and eminent Church leaders) in the days before such pronouncements were made (notably in the late fourth century). This is easily demonstrable by documenting many historical facts; for example:

- It was as late as 367 A.D. that St. Athanasius first listed the present 27 books of the New Testament.

- Moreover, St. Athanasius did seem to lower the status of the deuterocanonical books (Old Testament books accepted by Catholics but rejected by Protestants) somewhat, but not to a sub-biblical level. He cites Baruch, Wisdom, Sirach, Judith, Tobit, and Susanna without distinguishing them from other biblical books.

- James wasn’t even quoted by western Christians until around 350.

- There were also disputes regarding canonicity about Hebrews, 2 Peter, 2 John, 3 John, Jude, and Revelation well into the fourth century.

- In the same period, the Epistle of Barnabas and Shepherd of Hermas were included in the prominent manuscript Codex Sinaiticus, and 1 and 2 Clement in the Codex Alexandrinus.

- The Shepherd of Hermas was considered canonical by Irenaeus, Tertullian, Origen, and Clement of Alexandria, and the Didache and Epistle of Barnabas by the latter two. Clement of Alexandria accepted The Apocalypse of Peter as Scripture, and Origen thought The Acts of Paul should be in the Bible.

The canon issue is quite distinct from the question of biblical inspiration. All Catholics have contended is that an authoritative declaration of canonicity was necessary in order to settle the issue once and for all, lest disagreements continue on indefinitely without resolution. This is patently obvious from facts such as the above (and they are only the tip of the iceberg).

Another way of stating this is to say that the biblical books are not “self-attesting” to the extent that Christians would spontaneously all come to an agreement on the canon. It’s similar to the issue of perspicuity (clearness) of Scripture. There is no way to prove that it exists (in the way that Protestants claim), except for actual historical agreement.

But we know that is not the case, by observing denominations and competing theologies in Protestantism. Likewise, we know that the biblical books (though we believe them in faith to be inspired) are not all equally obvious as to their inspiration. Therefore, the Church was quite necessary to declare the canon and clear up any confusion. Yet Calvin oddly mocks and slams this as if it were at all controversial or historically arguable.

On the determination of the Church, therefore, it is said, depend both the reverence which is due to Scripture, and the books which are to be admitted into the canon. (I, 7:1)

Once again, Calvin resorts to a sleight-of-hand in mixing categories that don’t belong together at all. The “reverence which is due to Scripture” doesn’t depend on the Church at all, and the Catholic Church never states that it does. It’s a bum rap. But the canon is dependent historically on authoritative Church decisions. The former aspect is not intrinsically tied to the latter (except, apparently in Calvin’s head). It’s neither a logical nor historical juxtaposition.

Thus profane men, seeking, under the pretext of the Church, to introduce unbridled tyranny, care not in what absurdities they entangle themselves and others, provided they extort from the simple this one acknowledgement—viz. that there is nothing which the Church cannot do. (I, 7:1)

None of this follows at all, as just shown, so it is mere empty anti-Catholic rhetoric, packed with hyper-charged insulting words (profane, tyranny, absurdities) for polemical effect. Shame on Calvin! Later, however, he states the actual truth of the Catholic position (while being unaware that it is the Catholic position): “Add, moreover, that, for the best of reasons, the consent of the Church is not without its weight” (I, 8:12).

But what is to become of miserable consciences in quest of some solid assurance of eternal life, if all the promises with regard to it have no better support than man’s Judgment? On being told so, will they cease to doubt and tremble? On the other hand, to what jeers of the wicked is our faith subjected—into how great suspicion is it brought with all, if believed to have only a precarious authority lent to it by the good will of men? (I, 7:1)

This is all quite true. The only problem is that it is a straw man. None of this is taught by Catholicism. Therefore, Calvin is right in principle, but dead wrong in application of any of this to the Catholic Church.

Nor is there any room for the cavil, that though the Church derives her first beginning from thence, it still remains doubtful what writings are to be attributed to the apostles and prophets, until her Judgment is interposed. (I, 7:2)

Let it therefore be held as fixed, that those who are inwardly taught by the Holy Spirit acquiesce implicitly in Scripture; that Scripture, carrying its own evidence along with it, deigns not to submit to proofs and arguments, but owes the full conviction with which we ought to receive it to the testimony of the Spirit. Enlightened by him, we no longer believe, either on our own Judgment or that of others, that the Scriptures are from God; but, in a way superior to human Judgment, feel perfectly assured—as much so as if we beheld the divine image visibly impressed on it—that it came to us, by the instrumentality of men, from the very mouth of God. (I, 7:5)

We retort that if this were indeed the case, why was there so much significant disagreement on the canon in the early Church, as shown above? Many godly men did not see that several books we consider Scripture today were indeed Scripture, by self-attestation, and conversely, saw in non-biblical books attributes that led them to falsely conclude that they were inspired.

Such, then, is a conviction which asks not for reasons; such, a knowledge which accords with the highest reason, namely knowledge in which the mind rests more firmly and securely than in any reasons; such in fine, the conviction which revelation from heaven alone can produce. I say nothing more than every believer experiences in himself, though my words fall far short of the reality. I do not dwell on this subject at present, because we will return to it again: only let us now understand that the only true faith is that which the Spirit of God seals on our hearts. (I, 7:5)

This is far too simplistic and subjective. We do indeed receive illumination and confirmation and internal witness in our spirits, concerning the inspired revelation of God, but we’re not infallible in how we perceive or receive it. One cannot, as a result, casually eliminate (as Calvin does) the historical role of the Church in the determination of the canon.

It’s often been pointed out that this highly subjective criteria that Calvin offers is essentially no different from the Mormon “burning in the bosom” that leads them to accept many heterodox doctrines and indeed, three more allegedly “scriptural” writings beyond the Bible.

Ironically, Calvin recognizes the important role of the Old Testament priests in preserving Scripture (even citing a deuterocanonical book), while at the same time minimizing or cavalierly dismissing the role of the New Testament Church (i.e., the Catholic Church), as if the latter preservation was somehow of lesser importance than the former:

An objection taken from the history of the Maccabees (1 Macc. 1:57, 58) to impugn the credibility of Scripture, is, on the contrary, fitted the best possible to confirm it. First, however, let us clear away the gloss which is put upon it: having done so, we shall turn the engine which they erect against us upon themselves. As Antiochus ordered all the books of Scripture to be burnt, it is asked, where did the copies we now have come from? I, in my turn, ask, In what workshop could they have been so quickly fabricated? It is certain that they were in existence the moment the persecution ceased, and that they were acknowledged without dispute by all the pious who had been educated in their doctrine, and were familiarly acquainted with them. Nay, while all the wicked so wantonly insulted the Jews as if they had leagued together for the purpose, not one ever dared to charge them with having introduced spurious books. Whatever, in their opinion, the Jewish religion might be, they acknowledged that Moses was the founder of it. What, then, do those babblers, but betray their snarling petulance in falsely alleging the spuriousness of books whose sacred antiquity is proved by the consent of all history? But not to spend labour in vain in refuting these vile calumnies, let us rather attend to the care which the Lord took to preserve his Word, when against all hope he rescued it from the truculence of a most cruel tyrant as from the midst of the flames—inspiring pious priests and others with such constancy that they hesitated not, though it should have been purchased at the expense of their lives, to transmit this treasure to posterity, and defeating the keenest search of prefects and their satellites. (I, 8:10)

***

(originally 2012)

Photo credit: Historical mixed media figure of John Calvin produced by artist/historian George S. Stuart and photographed by Peter d’Aprix: from the George S. Stuart Gallery of Historical Figures archive [Wikimedia Commons / Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license]

***