replied in the combox of my paper, Prayers to Saints & for the Dead: Six Biblical Proofs [6-8-18]. His words will be in blue.

*****

First, I’d like to make a general statement. My critic starts with the accusation that what I did was “an attempt to legitimate an unbiblical doctrine.” Okay; if such a grandiose claim is made, then I would expect quite a bit of exegetical reasoning, other Bible passages introduced, Bible commentary, maybe delving into the Greek words, questioning my interpretations, showing how I quoted out of context. In other words it would be a meaty, in-depth biblical discussion.

Instead, what I got was six short bullet points: none longer than three sentences, and most only one or two. This is apparently regarded as a sufficient refutation of my extensive biblical argumentation. Most of my supporting arguments for the passages are utterly ignored, so that I have to repeat them now.

This is the problem, I’ve found, with much of Protestant counter-Catholic argumentation (believe me I know, having engaged in hundreds of debates). These sorts of “repluies” never get to the depth that they have to get to, in order to 1) refute the Catholic view, and 2) offer a more plausible biblical alternative. They don’t even directly address most of the biblical arguments we set forth.

My impression, reading the bible is complete different:

#1: if a parable or not, it is a conversation between two persons, both in the spiritual world after death.

Okay, here we go. I already dealt with the anticipated objection. Yet he makes it anyway, seemingly unaware that I did so, or else he would have offered counter-arguments to my supporting arguments. This is answered by what I already wrote (in green, with my added comments now):

1) Jesus couldn’t possibly teach doctrinal error by means of the story. And there are several, according to Protestant theology.

2) Abraham’s refusal to answer the prayer does not prove that he shouldn’t have been prayed to in the first place. Prayers can be refused. He never said, “You can’t pray to me!!!!! Pray only to God!” Protestants say we can’t pray to anyone but God. We can’t ask dead people to intercede to God for us. Jesus goes against both of those things by endorsing this story. He can’t teach falsehood in it. The rich man makes a petitionary prayer to Abraham, not God, in order to get a request. He doesn’t even ask him to go to God. He thinks that Abraham can himself answer it.

If indeed it were true that no one could ever pray to a creature rather than God, then Jesus couldn’t possibly have told this story. And Abraham would have certainly rebuked the rich man and would have told him to pray to God alone; and would have chided him for going to him instead of God. It’s irrelevant to the issue that the rich man was dead, because it remains wrong to pray to someone (alive or dead) other than God, in Protestantism. It wouldn’t suddenly become right (with an essential change of principle) just because he died. Therefore, the rich man would have violated that.

3) Abraham didn’t say, “I don’t have the power to send Lazarus and it’s blasphemous for you to think so.” He said, rather, that if he did send him, it wouldn’t make any difference as to the result Abraham hoped for. Thus, Abraham is presupposing that he has the power to answer a prayer request, but simply chooses not to, and explains to the rich man why.

4) Had Abraham fulfilled the request it would also be another instance of permitted communication between those in heaven or the afterlife (in this case, Hades) and those on earth, since the dead Lazarus would have returned to earth, to talk to the five brothers. Protestants tell us this is unbiblical and against God’s will (and is the equivalent of necromancy), yet there it is, right in Scripture, from Jesus.

5) If someone asks why we would even think of doing this in the first place, rather than going right to God, I address that, too (highlighting James 5:16: “The prayer of a righteous man has great power in its effects”):

#2: Samuel complains of having asked him. So an argument rather against…

Not at all. He doesn’t complain about being petitioned because (as Protestants would have it) no one should petition anyone but God. Rather, he questions the reasoning behind Saul’s action, by noting that God had already rejected Saul; therefore, why would he go to Samuel (as if Samuel the prophet of God would differ from God’s expressed will)? So Samuel says: “Why then do you ask me, since the LORD has turned from you and become your enemy?” (1 Sam 28:16). It’s a totally different thing from objecting to the prayer itself.

Far from refusing to answer the petition because no creature should ever do so, Samuel does answer, with three more sentences, but it’s a negative reply and a refusal: one that Saul doesn’t want to hear:

1 Samuel 28:17-19 (RSV) “The LORD has done to you as he spoke by me; for the LORD has torn the kingdom out of your hand, and given it to your neighbor, David. [18] Because you did not obey the voice of the LORD, and did not carry out his fierce wrath against Am’alek, therefore the LORD has done this thing to you this day. [19] Moreover the LORD will give Israel also with you into the hand of the Philistines; and tomorrow you and your sons shall be with me; the LORD will give the army of Israel also into the hand of the Philistines.”

#3: a misunderstanding of Jesus’ acclamation at the cross.

As with all the others, I dealt with the objection before it was made (then my argument was totally ignored).

[I]t was believed that one could pray to one such as Elijah (who had already appeared with Jesus at the transfiguration), and that he had power to come and give aid; to “save” a person (in this case, Jesus from a horrible death). It’s not presented in Matthew’s account as if they are wrong, and in light of other related Scriptures it is more likely that they are correct in thinking that this was a permitted scenario.

Jesus, after all , had already referred to Elijah, saying that he was the prototype for John the Baptist (Mt 11:14; 17:10-13; cf. Lk 1:17 from the angel Gabriel), and it could also have been known that Elijah and Moses appeared with Jesus at the transfiguration (Mt 17:1-6), if these were His followers.

#4: a wish of Paul, communicated to Timothy, it has nothing to do with a prayer directed to people who are already dead. Onesiphorus is more obviously still alive. Paul points to the fact of reward.

If it’s so obvious that Onesiphorus was still alive, then how odd that in a survey of 16 Protestant commentaries on the passage, I found that five of them held that he was “dead or likely dead” and eleven thought he was “possibly dead” or took a neutral stance. In a second paper surveying Protestant commentaries, I found 13 more who said that he was dead.

Again, these are Protestants and scholarly exegetes, not Catholics. If it’s true that he was dead, as these 18 Protestant Bible commentators believe, then this is explicit biblical evidence for prayer for the dead (case closed)!

#5: really 1 Corinthians 15:29 a difficult passage. Who seems to have the clear solution? But very risky to develop a doctrine of praying to Saints just by one bible verse.

It’s only one of six. Protestants offer no good interpretation of this odd verse. I offered (in a link) a plausible interpretation that makes perfect sense.

#6: In assurance by the Holy Spirit Peter and Jesus commanded a dead person to raise up (similarly to the command when Peter asked the lame man to stand on his feet, Acts 3:6.

Since my argument was completely ignored again, I repeat it for the convenience of readers:

Tabitha was a disciple in Joppa who died. Peter prayed to her when he said “Tabitha, rise.” See Acts 9:36-41. She was dead, and he was addressing her. There is no impenetrable wall between heaven and earth. This is not only praying to the dead, but for the dead, since the passage says that Peter “prayed” before addressing Tabitha first person. And he was praying for her to come back to life.

Our Lord Jesus does the same thing with regard to Lazarus. He prays for Lazarus (a dead man: John 11:41-42) and then speaks directly to a dead man (in effect, “praying” to him): “Lazarus, come out” (John 11:43).

This is absolutely and undeniably prayer for the dead, and right from the examples of Peter and Jesus. Our critic completely ignores the two prayers and goes right to the command. We can’t be too careful to ignore what goes against our argument! But in speaking to the two dead people, Peter and Jesus also violate Protestant teachings of men, which say that no one can attempt to communicate with a dead person: which is collapsed into the sinful category of necromancy or sorcery. Therefore, peter and Jesus committed those sins, if we believe Protestant theology.

Me: I’ll stick with a sinless Jesus (Who is God and can’t possibly sin), thank you. He prayed for the dead and talked to the dead. So did St. Peter. Therefore, it’s permissible for any Christian to do so, too. It’s really not complicated, but for Protestants coming along and denying / rejecting plain biblical teaching.

***

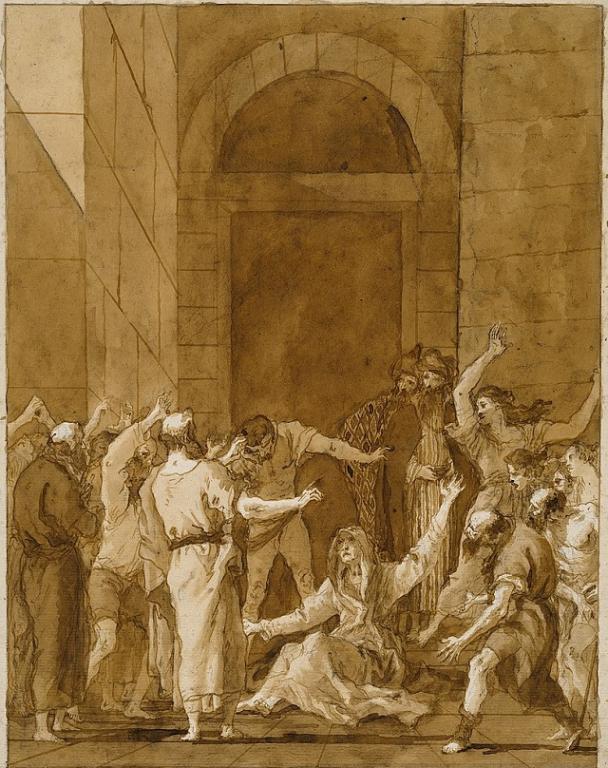

Photo credit: The Raising of Tabitha (early 1790s), by Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo (1727-1804) [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

***

Summary: A Protestant rejected my six biblical arguments for prayers to saints and for the dead but offered little argumentation. So I took the opportunity to strengthen my arguments all the more.

***