The Broad Definition of “King” in the Ancient Near East, + Biblical Use of “Chiefs of Edom”

Atheist anti-theist Jonathan M. S. Pearce is the main writer on the blog, A Tippling Philosopher. His “About” page states: “Pearce is a philosopher, author, blogger, public speaker and teacher from Hampshire in the UK. He specialises in philosophy of religion, but likes to turn his hand to science, psychology, politics and anything involved in investigating reality.” His words will be in blue.

*****

I am responding to a portion of Pearce’s article, Exodus Sidebar: Replying to Armstrong about Camels (5-24-21). Pearce cites Donald B. Redford, whom he describes as an “eminent Canadian Egyptologist and archaeologist” as an ally of his relentless, irrational biblical skepticism:

The author knows of kings in Moab (Jud. 2:12-30 [typo: should be 3:12-30]; 11:25) and Ammon (Jud. 11:13, 28), although these monarchies did not take shape until well into the first millennium B.C. [Egypt, Canaan, and Israel In Ancient Times, Princeton University Press, 1992, p. 277]

Here are the supposedly anachronistic biblical passages in question:

Judges 3:12 (RSV) . . . and the LORD strengthened Eglon the king of Moab against Israel . . .

Judges 3:14 . . . Eglon the king of Moab . . . [same in 3:15, 17]

Judges 11:13 . . . the king of the Ammonites . . . [same in 11:14, 28]

Judges 11:25 . . . Balak the son of Zippor, king of Moab . . . [cf. 11:17; Num 22:4, 10]

The web page, “Ancient Moabites of Jordan” states:

Origin: The Moabites were likely pastoral nomads settling in the trans-Jordanian highlands. They may have been among the raiders referred to as Habiru in the Amarna letters. Whether they were among the nations referred to in the Ancient Egyptian language as Shutu or Shasu is a matter of some debate among scholars. The existence of Moab prior to the rise of the Israelite polity can be seen from the colossal statues erected at Luxor by Pharaoh Ramesses II [r. 1279-1213 BC]. On the base of the second statue in front of the northern pylon of Rameses’ temple [the word] Mu’ab is listed among a series of nations conquered by the pharaoh.

The time-period of Ramesses II is right before the time of the book of Judges [c. 1200- c. 1037 BC]. Thus, we have archaeological evidence of some nation called Moab or Mu-ab in existence, when the book of Judges refers to it. The Luxor statue referencing Moab was written about in Journal of Near Eastern Studies (Vol. 52, No. 4. Oct., 1993).

Precursors of forerunners of the Moabites may have been the Shasu. Wikipedia describes them:

The Shasu . . . were Semitic-speaking cattle nomads in the Southern Levant from the late Bronze Age to the Early Iron Age or the Third Intermediate Period of Egypt. They were organized in clans under a tribal chieftain, and were described as brigands active from the Jezreel Valley to Ashkelon and the Sinai. . . . [source given for this claim: Chieftains of the Highland Clans: A History of Israel in the 12th and 11th Centuries BC, Robert D. Miller II, Wipf and Stock; Reprint edition, 2012, p. 95]

The earliest known reference to the Shasu occurs in a 15th-century BCE list of peoples in the Transjordan region. The name appears in a list of Egypt’s enemies inscribed on column bases at the temple of Soleb built by Amenhotep III. Copied later in the 13th century BCE either by Seti I or by Ramesses II at Amarah-West, the list mentions six groups of Shasu: the Shasu of S’rr, the Shasu of Rbn, the Shasu of Sm’t, the Shasu of Wrbr, the Shasu of Yhw, and the Shasu of Pysps.

Two Egyptian texts, one dated to the period of Amenhotep III (14th century BCE), the other to the age of Ramesses II (13th century BCE), refer to t3 š3św yhw, i.e. “Yahu in the land of the Šosū-nomads”, in which yhw[3]/Yahu is a toponym.

Øystein Sakala LaBianca (Ph.D. Brandeis University 1987) is Professor of Anthropology in the Department of Behavioral Sciences and Associate Director of the Institute of Archaeology at Andrews University. Randall W. Younker is Professor of Archaeology and History of Antiquity at the same university. Together, they wrote the book chapter, “The Kingdoms of Ammon, Moab, and Edom: The Archaeology of Society in Late Bronze/Iron Age Transjordan (Ca. 1400-500 BCE)” which is part of the book, The Archaeology of Society in the Holy Land (edited by Thomas E. Levy, London: Leicester University Press, 1995). Here are their opinions as to possible “kings” in the 11th and 12th c. BC in Moab and Ammon (present-day Jordan):

[T]he Ammonites, Moabites and Edomites were not true nation-states, but rather, are better described as ‘tribal kingdoms’. . . .

Nelson Glueck . . . define[d] the territories of their respective kingdoms from a string of border forts which he believed had already been built to protect their boundaries by the end of the thirteenth century BCE. Glueck’s conclusions were generally accepted by the scholars of his day . . .

When the authors discuss the Edomites (from the same general region), we see that their political situation was similar to the Moabites and Edomites and that the biblical accounts accurately reflect it:

Interestingly, the greater emphasis on network generating range-tied tribalism in the environmentally more severe territory of Edom may receive support from the ‘Edomite king list’ in Gen. 36. Scholars have long noted that none of the kings in this list was the son of his predecessor, and that each king is attributed to a different city. Moreover, these kings are introduced as ‘the kings who reigned in Edom, not kings of Edom’ . . . Regardless of when one would date this text . . . , it accurately reflects the proliferation of tribes and tribal chieftains which is typical of an ecologically hazardous region such as Edom.

Here are the relevant biblical passages:

Genesis 36:15-19, 21 These are the chiefs of the sons of Esau. The sons of El’iphaz the first-born of Esau: the chiefs Teman, Omar, Zepho, Kenaz, [16] Korah, Gatam, and Am’alek; these are the chiefs of El’iphaz in the land of Edom; they are the sons of Adah. [17] These are the sons of Reu’el, Esau’s son: the chiefs Nahath, Zerah, Shammah, and Mizzah; these are the chiefs of Reu’el in the land of Edom; they are the sons of Bas’emath, Esau’s wife. [18] These are the sons of Oholiba’mah, Esau’s wife: the chiefs Je’ush, Jalam, and Korah; these are the chiefs born of Oholiba’mah the daughter of Anah, Esau’s wife. [19] These are the sons of Esau (that is, Edom), and these are their chiefs. . . . [21] Dishon, Ezer, and Dishan; these are the chiefs of the Horites, the sons of Se’ir in the land of Edom.

Genesis 36:29-31, 40, 43 These are the chiefs of the Horites: the chiefs Lotan, Shobal, Zib’eon, Anah, [30] Dishon, Ezer, and Dishan; these are the chiefs of the Horites, according to their clans in the land of Se’ir. [31] These are the kings who reigned in the land of Edom, before any king reigned over the Israelites. . . . [40] These are the names of the chiefs of Esau, . . . [43] Mag’diel, and Iram; these are the chiefs of Edom (that is, Esau, the father of Edom), according to their dwelling places in the land of their possession. [“reigned” also appears ten times in Genesis 36: obviously referring to either a chief or king: 36:31 [2]; 32-39]

Exodus 15:15 Now are the chiefs of Edom dismayed; the leaders of Moab, trembling seizes them; . . .

1 Chronicles 1:43, 51-54 These are the kings who reigned in the land of Edom before any king reigned over the Israelites: . . . [51] And Hadad died. The chiefs of Edom were: chiefs Timna, Al’iah, Jetheth, [52] Oholiba’mah, Elah, Pinon, [53] Kenaz, Teman, Mibzar, [54] Mag’di-el, and Iram; these are the chiefs of Edom.

Everything here strikingly fits what we know from archaeology. The texts refer to “chiefs” (i.e., chieftains) of tribes “in” Edom (“chiefs of El’iphaz”; “chiefs of Reu’el”; “chiefs of the Horites”; “chiefs of Edom . . . according to their dwelling places in the land of their possession”). This fits with the understanding of Edom at this time being a collection of “tribal kingdoms.” In the two times they are referred to as “kings” (Gen 36:31; 1 Chr 1:43) the text says “kings who reigned in the land of Edom”: which is clearly synonymous in context to “chiefs” rather than a king of all of Edom. I think this gives us a clue as to the meaning of “king of Moab” and “king of the Ammonites” a little later in the book of Judges. Exodus 15:15 in an earlier period refers to “leaders of Moab” rather than kings, which is perhaps referring to chieftains also. But our authors have more to say about these matters:

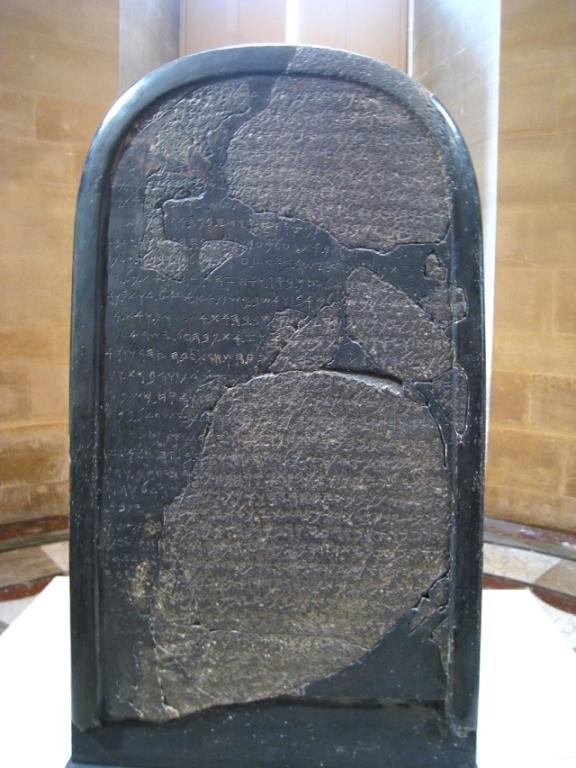

Although it is true that an ancient Near Eastern ‘king’ (milk, malik, malk, sharru) could include the head of an empire, state or tribe . . . there is evidence that the individuals who appropriated the title generally laid claim to power and influence that surpassed that of mere local bedouin shiekhs or village headmen. To see more precisely what the nature of this difference in power was, we shall take a closer look at the ninth century BCE polity of Mesha of Moab.

According to the Mesha inscription . . . Mesha identified himself as Dayboni, that is, a Dibonite. His people were called Dibonites and his place of residence was the city of Dibon . . . . However, he clearly claimed authority beyond the boundaries of his home city and people, for he was not merely the ruler of Dibon or the Dibonites; rather, he was the ‘king of Moab’. During times of external threat he could call upon ‘men from Moab’, that is, individuals from beyond his kin circle of ‘obedient’ or ‘loyal’ Dibonites. His ability to call up the ‘men from Moab’ clearly elevated him beyond the level of a local Dibonite sheikh or chief. Even Mesha’s enemies, the Israelites, who knew Mesha primarily as a ‘cattle magnate’ (noged, 2 Kgs 3:4), also recognized him as ‘king of Moab’ [“Now Mesha king of Moab was a sheep breeder . . .”: RSV]. . . . Mesha does not appear to have had jurisdiction over all land that was traditionally considered to be the land of Moab.

We see, then (assuming the correctness of the above anthropological / archaeological analysis), that the biblical use of “king of Moab” and “king of the Ammonites” is perfectly in keeping with what we know of those places at that time. It is not a biblical anachronism.

***

Related Reading

Edomites: Archaeology Confirms the Bible (As Always) [6-10-21]

Bible & Archaeology / Bible & Science (A Collection)

***

Photo credit: Mesha Stele: stele of Mesha, king of Moab, recording his victories against the Kingdom of Israel. Basalt, ca. 800 BCE. From Dhiban, now in Jordan [Wikimedia Commons / Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, 2.5 Generic, 2.0 Generic and 1.0 Generic license]

***

Summary: Atheist anti-theist Jonathan MS Pearce thinks that the book of Judges referring to Moabite & Ammonite kings is historical anachronism. I enlist archaeology to disprove this.

***

Tags: alleged Bible contradictions, alleged biblical anachronisms, Ammonite kings, Ammonites, ancient Hebrews, ancient Israelites, ancient Jews, anti-theism, archaeology & the Bible, archaeology & the Old Testament, atheists & the Bible, Bible “contradictions”, Bible “difficulties”, Bible & History, biblical accuracy, biblical anachronisms, biblical archaeology, Bronze Age, Hebrews, Holy Bible, infallibility, Iron Age, Late Bronze Age, Moabite & Ammonite Kings, Moabite kings, Moabites, Old Testament & history