Unpacking a Statement from Historian A. N. Sherwin-White

For Acts the confirmation of historicity is overwhelming. Yet Acts is, in simple terms and judged externally, no less of a propaganda narrative than the Gospels, liable to similar distortions. But any attempt to reject its basic historicity even in matters of detail must now appear absurd. Roman historians have long taken it for granted. (A. N. Sherwin-White, Roman Society and Roman Law in the New Testament, Oxford University Press, 1963, 173)

“Propaganda” is defined at Dictionary.com as: “information, ideas, or rumors deliberately spread widely to help or harm a person, group, movement, institution, nation, etc.” As long as “rumors” or “harm” aren’t involved (note the use of “or” above), there is nothing ethically wrong with this.

Thus, the Gospels and Luke are, of course, spreading the “propaganda” (“Information” or “ideas”) of the Gospel of Christianity: Jesus is Lord and God, and rose from the dead so that human beings can be saved. They are theological, and have that evangelistic message. No Christian or anyone else is going to deny that.

But it doesn’t follow that they are historically inaccurate, which is how and why historian A. N. Sherwin-White (not a believer) could and did make both points about them. He was a true, objective scholar. He could acknowledge if a source was historically accurate, regardless of whether it contained supernatural elements or not, or whether he himself was a Christian or not. He bowed to the actual objective evidence. May his tribe greatly multiply!

By “distortions” he was likely (I imagine) referring to the supernatural elements, which, presumably, he would be inclined to disbelieve. But he didn’t regard that as antithetical to general historical inaccuracy, which is precisely one of my arguments. I have cited him with regard to the latter, and his use of the word “propaganda” doesn’t overthrow that.

The etymology of the word shows that the derogative sense is of relatively recent origin. The Latin root word simply meant “propagate”. Hence, Merriam Webster online noted:

The History of Propaganda

Propaganda is today most often used in reference to political statements, but the word comes to our language through its use in a religious context. The Congregatio de propaganda fide (“Congregation for propagating the faith”) was an organization established in 1622 by Pope Gregory XV as a means of furthering Catholic missionary activity. The word propaganda is from the ablative singular feminine of propogandus, which is the gerundive of the Latin propogare, meaning “to propagate.” The first use of the word propaganda (without the rest of the Latin title) in English was in reference to this Catholic organization. It was not until the beginning of the 19th century that it began to be used as a term denoting ideas or information that are of questionable accuracy as a means of advancing a cause.”

Sherwin-White seems to be using it more so in the original, pre-19th century meaning of the word, since his reference to the extraordinary accuracy of Luke in the same context does not suggest lies or deliberate rumors, etc. We see this in another section of his book where he alludes to the “propaganda purposes” of the Gospel writers, yet at the same time cites Roman precedent for their likely accuracy regarding a certain aspect of the trial of Jesus:

The story of the reluctance, or at least the surprise, of Pilate, however much it may have been worked up for the propaganda purposes of the authors, is not without Julio-Claudian analogies. The Roman criminal courts were more familiar with the absentee accuser than with the defendant who would not defend himself. A series of ordinances beginning with a well-known decree of the Senate inspired by the emperor Claudius sought to protect defendants against defaulting accusers who left their victims, as Claudius complained, pendentes in albo, swinging idle on the court lists. But a better comparison comes from the procedure in the early martyr trials, first testified, but not first employed, seventy years later. Those who did not defend themselves were given three opportunities of changing their minds before sentence was finally given against them. This was an early technique already established as the regular thing before Pliny’s investigations in c. A.D. 110 . . . (p. 25; accessed via the Amazon book page‘s “Look Inside” feature, by searching for the word “propaganda”)

This aspect (corroborated by knowledge of 1st century Roman legal practices) of the defendant being given three chances at self-defense, having been initially silent, is clearly reflected in the Gospel accounts (highlighted in blue), where it seems that Pilate repeatedly allows Jesus to have His say and possibly avoid crucifixion:

Matthew 27:11-24 (RSV) Now Jesus stood before the governor; and the governor asked him, “Are you the King of the Jews?” Jesus said, “You have said so.” [12] But when he was accused by the chief priests and elders, he made no answer. [13] Then Pilate said to him, “Do you not hear how many things they testify against you?” [14] But he gave him no answer, not even to a single charge; so that the governor wondered greatly. [15] Now at the feast the governor was accustomed to release for the crowd any one prisoner whom they wanted. [16] And they had then a notorious prisoner, called Barab’bas. [17] So when they had gathered, Pilate said to them, “Whom do you want me to release for you, Barab’bas or Jesus who is called Christ?” [18] For he knew that it was out of envy that they had delivered him up. [19] Besides, while he was sitting on the judgment seat, his wife sent word to him, “Have nothing to do with that righteous man, for I have suffered much over him today in a dream.” [20] Now the chief priests and the elders persuaded the people to ask for Barab’bas and destroy Jesus. [21] The governor again said to them, “Which of the two do you want me to release for you?” And they said, “Barab’bas.” [22] Pilate said to them, “Then what shall I do with Jesus who is called Christ?” They all said, “Let him be crucified.” [23] And he said, “Why, what evil has he done?” But they shouted all the more, “Let him be crucified.” [24] So when Pilate saw that he was gaining nothing, but rather that a riot was beginning, he took water and washed his hands before the crowd, saying, “I am innocent of this man’s blood; see to it yourselves.”

Mark 15:1-15 And as soon as it was morning the chief priests, with the elders and scribes, and the whole council held a consultation; and they bound Jesus and led him away and delivered him to Pilate. [2] And Pilate asked him, “Are you the King of the Jews?” And he answered him, “You have said so.” [3] And the chief priests accused him of many things. [4] And Pilate again asked him, “Have you no answer to make? See how many charges they bring against you.” [5] But Jesus made no further answer, so that Pilate wondered. [6] Now at the feast he used to release for them one prisoner for whom they asked. [7] And among the rebels in prison, who had committed murder in the insurrection, there was a man called Barab’bas. [8] And the crowd came up and began to ask Pilate to do as he was wont to do for them. [9] And he answered them, “Do you want me to release for you the King of the Jews?” [10] For he perceived that it was out of envy that the chief priests had delivered him up. [11] But the chief priests stirred up the crowd to have him release for them Barab’bas instead. [12] And Pilate again said to them, “Then what shall I do with the man whom you call the King of the Jews?” [13] And they cried out again, “Crucify him.” [14] And Pilate said to them, “Why, what evil has he done?” But they shouted all the more, “Crucify him.” [15] So Pilate, wishing to satisfy the crowd, released for them Barab’bas; and having scourged Jesus, he delivered him to be crucified.

The Gospel of Luke again shows Pilate giving Jesus every opportunity to defend himself, and being inclined to release him (Lk 23:4, 14-16, 22). The Gospel of John does the same, with a detailed discussion with Pilate and Jesus, not included in the other Gospels (see Jn 18:38-39; 19:4, 6, 10, 12, 15).

Elsewhere in his book, Sherwin-White casually refers to “the accuracy of Acts about Ephesus” (p. 90). He notes that the three synoptic Gospels are “technically correct” regarding fine legal points of Jesus’ trial:

On certain technical points, such as the reference to the tribunal and the formulation of the sentence, Mark and Matthew are superior. But Luke is remarkable in that his additional materials — the full formulation of the charges before Pilate, the reference to Herod, and the proposed acquittal with admonition — are all technically correct. (p. 32)

He believes that the account of the trial of Jesus in the Gospel of John is also historically probable:

[I]t is apparent that there is no historical improbability in the Johannine variations of this sort from the synoptic version. The framework of the trial is not notably inferior to that of Luke. It begins with a formal delation — ‘What accusation bring ye against this man?’ [Jn 18:29] — and ends with a formal condemnation pro tribunali. [Jn 19:13] . . . the principal novelty — the implication that Pilate adopted, or was willing to adopt, the sentence of the Sanhedrin — is entirely within the scope of the procurator’s imperium. (p. 47)

The telling phrase — ‘If you let this man go, you are not Caesar’s friend’ — recalls the frequent manipulation of the treason law for political ends in Roman public life, and uses a notable political term — Caesarus amicus — to enforce its point. [Jn 19:12] (p. 47)

Sherwin-White on the same page calls this a “convincing technicality by John” and in a footnote at the bottom, notes: “The term ‘friend of Caesar’ is used in a very similar way to that of the Gospel in passages of the contemporary Philo. Cf. In. Flaccum, 2. 40.” He also compares the Gospel writers favorably with the ancient Greek historian Herodotus:

Herodotus particularly comes to mind. In his history, written in mid-fifth century B.C., we have a fund of comparable material in the tales of the period of the Persian Wars and the preceding generation. These are retold by Herodotus from forty to seventy years later, after they had been remodelled by at least one generation of oral transmission. The parallel with the authors of the Gospels is by no means so far-fetched as it might seem. Both regard their material with enthusiasm rather than detached criticism. (p. 189)

All of this suggests one thing: if the Gospels have some “propagandistic” elements (in the permissible, non-lying original meaning of the word), it doesn’t follow that they (especially Luke) are not historically accurate to an extraordinary degree. This appears to be Sherwin-White’s scholarly opinion, as a reputable historian and expert in Roman law.

Nothing above from his own words suggests that I have misquoted him at all, since all I was supporting in using his words was the proposition that Luke is historically accurate, as much as any ancient historian, while not denying for a moment that the Gospels also definitely propagate the Gospel message of salvation; that is, the original meaning of the word propaganda, which now has an entirely negative slant to it. The two things are not mutually exclusive. Sherwin-White didn’t think so, from a secular historian’s point of view; nor do I, from a Christian apologetics and evangelistic point of view.

***

Practical Matters: Perhaps some of my 4,000+ free online articles (the most comprehensive “one-stop” Catholic apologetics site) or fifty books have helped you (by God’s grace) to decide to become Catholic or to return to the Church, or better understand some doctrines and why we believe them.

Or you may believe my work is worthy to support for the purpose of apologetics and evangelism in general. If so, please seriously consider a much-needed financial contribution. I’m always in need of more funds: especially monthly support. “The laborer is worthy of his wages” (1 Tim 5:18, NKJV). 1 December 2021 was my 20th anniversary as a full-time Catholic apologist, and February 2022 marked the 25th anniversary of my blog.

PayPal donations are the easiest: just send to my email address: [email protected]. You’ll see the term “Catholic Used Book Service”, which is my old side-business. To learn about the different methods of contributing, including 100% tax deduction, etc., see my page: About Catholic Apologist Dave Armstrong / Donation Information. Thanks a million from the bottom of my heart!

***

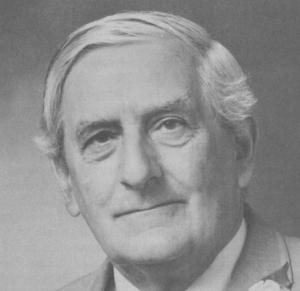

Photo credit: A. N. Sherwin-White, from between 1974-1977; courtesy of Cambridge.org / Cambridge University Press.

***

Summary: Secular historian A. N. Sherwin-White (1911-1994) would answer “yes” to the question: “Are the Gospels & Acts “Propaganda”?” while at the same time affirming their exceptional historical accuracy (especially that of Luke).