Rev. Dr. Jordan B. Cooper is a Lutheran pastor, adjunct professor of Systematic Theology, Executive Director of the popular Just & Sinner YouTube channel, and the President of the American Lutheran Theological Seminary (which holds to a doctrinally traditional Lutheranism, similar to the Lutheran Church – Missouri Synod). He has authored several books, as well as theological articles in a variety of publications.

*****

I will be responding to the first “papacy portion” of Jordan’s YouTube video, “Five Reasons I Am Not Roman Catholic” (1-27-19). When I cite his words directly, they will be in blue, and citations and descriptions of his arguments will be accompanied by the time in the video as well.

1) The Papacy. . . . The claims regarding the papacy I simply don’t see as historically verifiable, and I also do not see them exegetically. I don’t see them as being taught in Scripture. . . . Matthew 16 is the one that’s often pointed to. . . . Even if you are to argue that Peter is indeed the Rock, . . . that still does not prove that there is any truth to the claims about the successors of St. Peter. [1:08-2:32]

See my papers, for the general Catholic “Petrine” or “papal” argument from Scripture:

50 New Testament Proofs for Petrine Primacy & the Papacy [1994]

Primacy of St. Peter Verified by Protestant Scholars [1994]

Can Christ & Peter Both be “Rocks”? [4-21-22]

See also: “Protestant Scholars on Matthew 16:16-19” (Nicholas Hardesty) [9-4-06]

As to papal succession, most Christians agree that St. Peter was the leader of the early Church and the disciples: whether they believe he was a “pope” or not. It stands to reason, then, that there would continue to be a leader, just as there was a first President when the laws of the United States were established at the Constitutional Convention in 1787.

Why have one President and then cease to have one thereafter and let the executive branch of government exist without a leader? Everyone understands that there is then a succession of Presidents and that it doesn’t end with the first one and the prototype.

So why do people think so differently when it comes to Christianity, which is in need of a governing body and person at the top of the chain of authority, just as any effective organization whatever has? Catholics are, therefore, applying common sense: if this is how Jesus set up the government of His Church in the beginning, then it ought to continue in like fashion, in perpetuity.

If indeed an office of the pope was truly intended to be set up by Jesus, why in the world would anyone think it was solely for the lifetime of Peter and then it would vanish? The Church supposedly had a supervisor for ten, twenty years, but then never did again? That makes no sense. What would be the point?

When other offices are referred to in the Bible (excepting the apostles and perhaps prophets: but there is a biblical argument that bishops are the successors of the apostles), they were clearly regarded as permanent and ongoing (deacons, elders, pastors / priests / bishops). By analogy, then, it follows that this office is perpetual, just as the others are. It also makes sense to have a chief bishop.

Moreover, the very nature of the concept of office is that it is larger than one mere person who occupies it: even the first and most extraordinary one who does. It’s quite obvious that Jesus’ commissioning of Peter was the creation of a new office or position: having to do with the governance of the Church and jurisdiction and power.

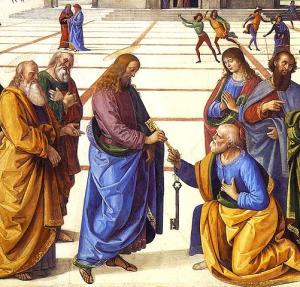

Moreover, the consensus of Bible scholars today (including Protestants) is that the notion of “keys of the kingdom of heaven” given to Peter by Jesus (Mt 16:19) hearkens back to the Old Testament:

Isaiah 22:22-24 (RSV) And I will place on his shoulder the key of the house of David; he shall open, and none shall shut; and he shall shut, and none shall open. [23] And I will fasten him like a peg in a sure place, and he will become a throne of honor to his father’s house. [24] And they will hang on him the whole weight of his father’s house, the offspring and issue, every small vessel, from the cups to all the flagons. (cf. 36:3, 22)

This was a supervisory office. The great Protestant Bible scholar, F. F. Bruce observed:

The keys of a royal or noble establishment were entrusted to the chief steward or majordomo; . . . About 700 B.C. an oracle from God announced that this authority in the royal palace in Jerusalem was to be conferred on a man called Eliakim . . . (Isa. 22:22). So in the new community which Jesus was about to build, Peter would be, so to speak, chief steward. (The Hard Sayings of Jesus, Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press, 1983, 143-144)

If the direct analogy understood in the commission refers to an office itself inherently possessing succession, as a matter of historical fact (according to Old Testament scholars and ancient Near East historians), then it follows that the papacy also has succession as one of its inherent characteristics. This is purely logical and based on facts concerning the office that is the basis of the analogy. In that sense it is even explicit in Scripture.

Jordan then talked about how there are bishops in the NT and Church history, and that this is good. At that point, I ask again: why have leaders in local churches, but not one leader of the whole Church? Why have a leader of the disciples, but not a leader of the bishops, who were the successors of the disciples / apostles? I would say that in fact we observe Peter acting as such a leader of the Church throughout the first half of the book of Acts and in the Jerusalem Council (Acts 15).

We see him writing very much as a pope would write in his First Epistle, which was written from Rome in general homiletic, or “hortatory” fashion (though not to all Christian inhabitants of the known world, which is not required for my point to stand) as (according to Guthrie and The Eerdmans Bible Dictionary) a “circular letter” (much like a papal encyclical is today). In fact, if we look up encyclical in the dictionary, we find that it comes from the Latin encyclicus and the Greek enkyklios, meaning, literally, “in a circle, general, common, for general circulation.” The word encyclopedia is derived from the same root. Renowned Protestant Bible scholar J. B. Lightfoot comments on this passage as follows:

St. Peter, giving directions to the elders, claims a place among them. The title ‘fellow-presbyter,’ which he applies to himself, would doubtless recall to the memory of his readers the occasions when he himself had presided with the elders and guided their deliberations. (St. Paul’s Epistle to the Philippians, Lynn, Massachusett: Hendrickson Pub., 1982, 198; emphasis added)

Furthermore, we have St. Clement of Rome decidedly acting like a pope before 100 AD in his letter to the Corinthians:

Pope St. Clement of Rome & Papal Authority [7-28-21]

Is First Clement Non-Papal? (vs. Jason Engwer) [4-19-22]

Jordan argues that early Church documents don’t refer to a pope. For example, St. Ignatius of Antioch doesn’t seem to be aware of a pope. But he ignores the strong evidence of 1 Clement, which is very early as well. St. John Henry Cardinal Newman offers a cogent explanation as to why the papacy is rather subdued and manifest relatively less in the earlier centuries of the Church (and specifically a reason for Ignatius’ silence on the matter):

Let us see how, on the principles which I have been laying down and defending, the evidence lies for the Pope’s supremacy.*As to this doctrine the question is this, whether there was not from the first a certain element at work, or in existence, divinely sanctioned, which, for certain reasons, did not at once show itself upon the surface of ecclesiastical affairs, and of which events in the fourth century are the development; and whether the evidence of its existence and operation, which does occur in the earlier centuries, be it much or little, is not just such as ought to occur upon such an hypothesis.*For instance, it is true, St. Ignatius is silent in his Epistles on the subject of the Pope’s authority; but if in fact that authority could not be in active operation then, such silence is not so difficult to account for as the silence of Seneca or Plutarch about Christianity itself, or of Lucian about the Roman people. St. Ignatius directed his doctrine according to the need. While Apostles were on earth, there was the display neither of Bishop nor Pope; their power had no prominence, as being exercised by Apostles. In course of time, first the power of the Bishop displayed itself, and then the power of the Pope. . . .*

St. Peter’s prerogative would remain a mere letter, till the complication of ecclesiastical matters became the cause of ascertaining it. While Christians were “of one heart and soul,” it would be suspended; love dispenses with laws . . .*When the Church, then, was thrown upon her own resources, first local disturbances gave exercise to Bishops, and next ecumenical disturbances gave exercise to Popes; and whether communion with the Pope was necessary for Catholicity would not and could not be debated till a suspension of that communion had actually occurred. It is not a greater difficulty that St. Ignatius does not write to the Asian Greeks about Popes, than that St. Paul does not write to the Corinthians about Bishops. And it is a less difficulty that the Papal supremacy was not formally acknowledged in the second century, than that there was no formal acknowledgment on the part of the Church of the doctrine of the Holy Trinity till the fourth. No doctrine is defined till it is violated . . .*Moreover, an international bond and a common authority could not be consolidated, were it ever so certainly provided, while persecutions lasted. If the Imperial Power checked the development of Councils, it availed also for keeping back the power of the Papacy. The Creed, the Canon, in like manner, both remained undefined. The Creed, the Canon, the Papacy, Ecumenical Councils, all began to form, as soon as the Empire relaxed its tyrannous oppression of the Church. And as it was natural that her monarchical power should display itself when the Empire became Christian, so was it natural also that further developments of that power should take place when that Empire fell. Moreover, when the power of the Holy See began to exert itself, disturbance and collision would be the necessary consequence . . . as St. Paul had to plead, nay, to strive for his apostolic authority, and enjoined St. Timothy, as Bishop of Ephesus, to let no man despise him: so Popes too have not therefore been ambitious because they did not establish their authority without a struggle. It was natural that Polycrates should oppose St. Victor; and natural too that St. Cyprian should both extol the See of St. Peter, yet resist it when he thought it went beyond its province . . .*On the whole, supposing the power to be divinely bestowed, yet in the first instance more or less dormant, a history could not be traced out more probable, more suitable to that hypothesis, than the actual course of the controversy which took place age after age upon the Papal supremacy.*It will be said that all this is a theory. Certainly it is: it is a theory to account for facts as they lie in the history, to account for so much being told us about the Papal authority in early times, and not more; a theory to reconcile what is and what is not recorded about it; and, which is the principal point, a theory to connect the words and acts of the Ante-nicene Church with that antecedent probability of a monarchical principle in the Divine Scheme, and that actual exemplification of it in the fourth century, which forms their presumptive interpretation. All depends on the strength of that presumption. Supposing there be otherwise good reason for saying that the Papal Supremacy is part of Christianity, there is nothing in the early history of the Church to contradict it . . .*Moreover, all this must be viewed in the light of the general probability, so much insisted on above, that doctrine cannot but develop as time proceeds and need arises, and that its developments are parts of the Divine system, and that therefore it is lawful, or rather necessary, to interpret the words and deeds of the earlier Church by the determinate teaching of the later. (Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine, 1878 edition, Univ. of Notre Dame Press, 1989, pp. 148-155; Part 1, Chapter 4, Section 3)

*

I debated this with Reformed anti-Catholic apologist James White way back in August 1997:

Pope Silvester and the Council of Nicaea (vs. James White)

From Acts 15, we learn that “after there was much debate, Peter rose” to address the assembly (15:7). The Bible records his speech, which goes on for five verses. Then it reports that “all the assembly kept silence” (15:12). Paul and Barnabas speak next, not making authoritative pronouncements, but confirming Peter’s exposition, speaking about “signs and wonders God had done through them among the Gentiles” (15:12). Then when James speaks, he refers right back to what “Simeon [Peter] has related” (15:14). To me, this suggests that Peter’s talk was central and definitive. James speaking last could easily be explained by the fact that he was the bishop of Jerusalem and therefore the “host.”

St. Peter indeed had already received a relevant revelation, related to the council. God gave him a vision of the cleanness of all foods (contrary to the Jewish Law: see Acts 10:9-16). St. Peter is already learning about the relaxation of Jewish dietary laws, and is eating with uncircumcised men, and is ready to proclaim the gospel widely to the Gentiles (Acts 10 and 11).

This was the secondary decision of the Jerusalem Council, and Peter referred to his experiences with the Gentiles at the council (Acts 15:7-11). The council then decided — with regard to food –, to prohibit only that which “has been sacrificed to idols and from blood and from what is strangled” (15:29).

*

Practical Matters: Perhaps some of my 4,000+ free online articles (the most comprehensive “one-stop” Catholic apologetics site) or fifty books have helped you (by God’s grace) to decide to become Catholic or to return to the Church, or better understand some doctrines and why we believe them.

Or you may believe my work is worthy to support for the purpose of apologetics and evangelism in general. If so, please seriously consider a much-needed financial contribution. I’m always in need of more funds: especially monthly support. “The laborer is worthy of his wages” (1 Tim 5:18, NKJV). 1 December 2021 was my 20th anniversary as a full-time Catholic apologist, and February 2022 marked the 25th anniversary of my blog.

PayPal donations are the easiest: just send to my email address: [email protected]. You’ll see the term “Catholic Used Book Service”, which is my old side-business. To learn about the different methods of contributing, including 100% tax deduction, etc., see my page: About Catholic Apologist Dave Armstrong / Donation Information. Thanks a million from the bottom of my heart!

***