And Was it the Prototype of Ecumenical Councils or Merely a Local Synod?

This is a discussion I had on my Facebook page with Fr. Daniel G. Dozier, a good friend of mine who is a Byzantine Catholic priest, and my co-author of the book, Orthodoxy and Catholicism: A Comparison (3rd revised edition: July 2015, 335 pages). His words will be in blue. He likely has more to say. If so, that will be added to this dialogue.

*****

[for background, read Acts 15]

Saint Peter did not preside at the council of Jerusalem.

Ah, east and west. Here is the argument for St. Peter presiding, as I understand it, from a 2017 article of mine (some repetition from the above and some new elements, too):

*

From Acts 15, we learn that “after there was much debate, Peter rose” to address the assembly (15:7). The Bible records his speech, which goes on for five verses. Then it reports that “all the assembly kept silence” (15:12). Paul and Barnabas speak next, not making authoritative pronouncements, but confirming Peter’s exposition, speaking about “signs and wonders God had done through them among the Gentiles” (15:12). Then when James speaks, he refers right back to what “Simeon [Peter] has related” (15:14). To me, this suggests that Peter’s talk was central and definitive. James speaking last could easily be explained by the fact that he was the bishop of Jerusalem and therefore the “host.”

St. Peter indeed had already received a relevant revelation, related to the council. God gave him a vision of the cleanness of all foods (contrary to the Jewish Law: see Acts 10:9-16). St. Peter is already learning about the relaxation of Jewish dietary laws, and is eating with uncircumcised men, and is ready to proclaim the gospel widely to the Gentiles (Acts 10 and 11).*

This was the secondary decision of the Jerusalem Council, and Peter referred to his experiences with the Gentiles at the council (Acts 15:7-11). The council then decided — with regard to food –, to prohibit only that which “has been sacrificed to idols and from blood and from what is strangled” (15:29).

*

Catholic apologist Mark Bonocore expands upon this:

*

Jerusalem Council: Orthodox or Catholic style of council?

So, did the Jerusalem Council operate like the Orthodox model of an Ecumenical council? Or rather like the Catholic model? Here’s how it worked:*The bishops met TO EXAMINE the matter. They DEBATED.*Then, Peter — after listening to the debate — gave HIS TEACHING (vox Petros).*After this, the Council FALLS SILENT (a la, the Tome of Leo).*Then, Paul and Barnabas were permitted to tell about their first missionary journey so as to back up Peter’s teaching with signs from the Holy Spirit (e.g. as in the Immaculate Conception dogma backed up by the miracles at Lourdes).*And, thereafter, James gives a ruling. And, THIS is the only thing that seems unCatholic to some.*However, whereas it does say (in verse 13) how Paul and Barnabas “fall silent,” allowing James to respond, this does not take away from the entire assembly “falling silent” after Peter’s teaching in verse 12. Why? Because we are dealing with 2 Greek words. In 13, the verb is “sigesai” (infinitive aorist: meaning that Paul and Barnabas finished talking). In verse 12, it’s “esigese” (past tense aorist usage — meaning that the assembly REMAINED SILENT after Peter’s address). And, indeed, after Peter speaks, all debate stops. The matter had been settled.*So, why does James speak?*We think there are three reasons:*He’s the bishop of Jerusalem. Peter was just a visitor.*

What he says, he …like Paul and Barnabas …ties into Peter’s declaration: “Brothers, listen to me. SYMEON has described how God…” etc.*And, most importantly, because James was the leader of the Church’s “Jewish wing.” Remember, in verse 1 and 2 how Acts 15 describes:*“Some who had come DOWN FROM JUDAEA were instructing the brothers, ‘Unless you are circumcised according to the Mosaic practice, you cannot be saved.’

*They were coming FROM JAMES! They were HIS disciples! Therefore, he renders judgment on the matter for his Jewish party, not as a superior or equal of Peter at all. And, this is MOST clear in verse 19, where it says:*“It is my judgment, therefore, that WE ought to STOP TROUBLING THE GENTILES.”*Who was “troubling” the Gentiles? Not Paul and Barnabas. Not Peter and his disciples, who Baptised the first Gentiles without circumcision. So, who? ONLY the Jewish Christians under James. Therefore, it is NOT the whole Church, but only the “Jewish party” that James is giving a “judgment” to.

*So again, the Council of Jerusalem was not an Ecumenical Council by Byzantine Orthodox definition. Rather, it was COMPLETELY based on the Petrine teaching office: the magisterium of the Church.

*

Thanks for the reply. Here is what I just posted on my page.

*

DID ST PETER PRESIDE OVER THE COUNCIL OF JERUSALEM?

*

This to me is an interesting and important question in part because it highlights the importance of Petrine primacy in support of local or regional primacy. Here I defer to Pope St John Paul II:

*

“The first part of the Acts of the Apostles presents Peter as the one who speaks in the name of the apostolic group and who serves the unity of the community—all the while respecting the authority of James, the head of the Church in Jerusalem. This function of Peter must continue in the Church so that under her sole Head, who is Jesus Christ, she may be visibly present in the world as the communion of all his disciples.” – Ut Unum Sint, #97

*

It is simply an anachronistic reading to say that Peter “presided” over the Council, when in fact (as the Pope references) he spoke in the name of the apostolic community and in service to the unity of the brethren, while respecting the authority of James. What authority was that? To preside over the Council as the head of the local Church in Jerusalem.

*

I certainly agree with Petrine primacy and believe that this is a model for how it can and should function – in service to unity and to the strengthening of the local and regional authority of bishops, not in presiding over every activity, including Synodal activities.

*

Fr. Daniel,

*

I think we are basically quibbling over the meaning of “preside.” I used it in a way to mean that Peter had the greater overall authority. But it can also be used to denote administrative or procedural authority or in the sense of the “local bishop presiding over his own jurisdiction.” St. James did the latter (I agree; I don’t think anyone disagrees about that). But Peter had more authority overall. I don’t see that this disagrees at all with what Pope St. John Paul II wrote (Peter represents the apostles while James is Bishop of Jerusalem).

*

Mark Bonocore wrote in another part of his article that I didn’t cite: “It is interesting to note that, in Acts 15, Peter does not act as a bishop of a see. Rather, he is merely a visitor. Yet, his Petrine office and teaching authority are in place — even over the resident reigning bishop (James).”

I agree.

*

I think another issue is what we view the Jerusalem Council as representing (as a prototype or analogy). There is a sense in which it was a local council and also by analogy, the prototype of what was to become the ecumenical council. It’s the only example of a council (after Pentecost) in the NT that we have. And so if we are to learn about the nature of an ecumenical council in the NT, this is it. I believe that we could find statements from popes and theologians expressing this analogy.

*

Thus, in the “prototype of ecumenical councils” model, Peter would obviously ultimately preside. But in the “local council” perspective it would be James.

*

*

Is it only a local council, though? I say that it clearly wasn’t, because its decision (about circumcision and clean food requirements) was binding thereafter on the entire Church: not just Jerusalem (which would be the case in a merely local council).

*

*

Hence, Paul pronounces the decision as binding upon the Christians in all the cities he was visiting in Asia Minor [Turkey] (Acts 16:4). Therefore, the Jerusalem Council is more a model of an ecumenical council, in my opinion: because of who is affected by its decision (the entire Church). If we say that a local bishop presided over a decision that affected the entire universal Church all through history, I think that is a mix-up of categories and makes little sense. But if we view Peter as “presiding” in the sense of ultimate authority and the issuance of the central proclamation, then it makes more sense of a universal decision being presided over by the universal bishop.

*

It might be objected that with regard to the Deuterocanon, local councils were originally the ones that declared it. But those were ratified by the pope. Thus, for the rulings of the Jerusalem Council to be universally binding, would they not have to be “ratified” by the first pope, Peter (whether he technically “presided” in the sense that we agree James did or not)? I think so.

*

Moreover, by further analogy (can you tell that I love that sort of argument?), the book of Acts, prior to this council, had already presented Peter as overwhelmingly preeminent in the early apostolic Church:

*

1) Peter’s name occurs first in a list of the apostles (Acts 1:13; cf. 2:37).2) Peter is regarded by the Jews (Acts 4:1-13) as the leader and spokesman of Christianity.3) Peter is regarded by the common people in the same way (Acts 2:37-41; 5:15).

4) Peter’s words are the first recorded and most important in the upper room before Pentecost (Acts 1:15-22).5) Peter takes the lead in calling for a replacement for Judas (Acts 1:22).6) Peter is the first person to speak (and only one recorded) after Pentecost, so he was the first Christian to “preach the gospel” in the Church era (Acts 2:14-36).7) Peter works the first miracle of the Church Age, healing a lame man (Acts 3:6-12).8 ) Peter utters the first anathema (Ananias and Sapphira) emphatically affirmed by God (Acts 5:2-11)!9) Peter’s shadow works miracles (Acts 5:15).10) Peter is the first [named] person after Christ to raise the dead (Acts 9:40).11) Cornelius is told by an angel to seek out Peter for instruction in Christianity (Acts 10:1-6).12) Peter is the first to receive the Gentiles, after a revelation from God (Acts 10:9-48).13) Peter instructs the other apostles on the catholicity (universality) of the Church (Acts 11:5-17).14) Peter is the object of the first divine interposition on behalf of an individual in the Church Age (an angel delivers him from prison – Acts 12:1-17).15) The whole Church (strongly implied) offers “earnest prayer” for Peter when he is imprisoned (Acts 12:5).16) Peter is the first to recognize and refute heresy, in Simon Magus (Acts 8:14-24).17) Peter’s proclamation at Pentecost (Acts 2:14-41) contains a fully authoritative interpretation of Scripture, a doctrinal decision and a disciplinary decree concerning members of the “House of Israel” (2:36) – an example of “binding and loosing.”18 ) Peter was the first “charismatic”, having judged authoritatively the first instance of the gift of tongues as genuine (Acts 2:14-21).19) Peter is the first to preach Christian repentance and baptism (Acts 2:38).20) Peter (presumably) takes the lead in the first recorded mass baptism (Acts 2:41).21) Peter commanded the first Gentile Christians to be baptized (Acts 10:44-48).22) Peter was the first traveling missionary, and first exercised what would now be called “visitation of the churches” (Acts 9:32-38,43). Paul preached at Damascus immediately after his conversion (Acts 9:20), but hadn’t traveled there for that purpose (God changed his plans!). His missionary journeys begin in Acts 13:2.

*

So — again, by analogy — when we get to the Jerusalem Council isn’t it plausible to ALSO think that Peter had the greatest authority? Whether James presided as local bishop doesn’t affect Peter’s overall authority as pope and head of the universal Church. And he exercised that at this council, by delivering the central and definitive message. In the first part of Ut Unum Sint #97, Pope St. John Paul II also wrote:

*

The Catholic Church, both in her praxis and in her solemn documents, holds that the communion of the particular Churches with the Church of Rome, and of their Bishops with the Bishop of Rome, is—in God’s plan—an essential requisite of full and visible communion. Indeed full communion, of which the Eucharist is the highest sacramental manifestation, needs to be visibly expressed in a ministry in which all the Bishops recognize that they are united in Christ and all the faithful find confirmation for their faith.

*

I will come back to this later, but for now let me only say that I think we need to consider a couple of points.

*

First, to preside at a council even if it is simply a council in seed form is to preside over an act of the magisterium – in this particular case and apostolic magisterium. I don’t think we should reduce the role of James to purely an administrative one when in fact very clearly he speaks for the whole council and renders an authoritative judgment in the name of all present.

*

Second, I think the issue of who has more authority is really an attempt to read into a narrative a concern that is not being answered or addressed by the narrative. It is essentially to ask the question – what if James had disagreed with Peter, could he have rendered a different judgment? Such a notion would have really been foreign to the concerns or spirit of the apostolic age, so again I think what we have here is an anachronistic reading addressing later theological concerns. I’m not saying it is entirely illegitimate, nor am I saying that James would or could have disagreed with Peter at this point. I think he rightfully identifies this act of the council as a work of the Holy Spirit.

*

All that being said, I do not disagree with the importance of Peter’s role and his authority in all of this, although there is a definite shift in focus from Peter to Paul in the book of Acts. But I do not believe that it can be said that he (Peter) is presiding over this council and I think the Pope is pointing this out, Nor do I see the necessity of arguing that he is presiding here in order to support Petrine primacy as I indicated.

*

I don’t think I’m being “anachronistic” at all, though it’s possible: more on that below. I’m simply analyzing a “primitive” instance of ecclesiastical / ecclesiological matters that obviously highly developed through the centuries.

*

We have to actually address the biblical texts involved and exegete them to have this discussion, no? I have presented (rightly or wrongly) many dozens of them.

*

The Bible is not gonna offer a full-fledged, fully developed ecclesiology: however we construe what that is. That’s why I speak of models and prototypes and analogies, because the ecclesiology of Latin Catholicism or Eastern Catholicism or Orthodoxy (or any form of Protestantism) will not be seen in its fullness in Scripture.

*

I have no problem whatsoever with the jurisdiction of each bishop in his own See. James presided in that sense. That’s Catholic teaching. But it’s a question about who has more authority over a council whose decisions were interpreted by no less than St. Paul as having essentially universal binding application.

*

The Jerusalem Council occurred as the Church was just starting to determine how it would run itself. It had elements of being a local council, and also (I would say, much stronger) elements of being the prototype of an ecumenical council. I think that’s why we can have these two somewhat differing interpretations, that I actually think aren’t far apart at all.

*

We both bring the bias of eastern and western ecclesiology in how we approach and exegete the text (let’s not fool ourselves). If I have a bias leading to “anachronism” so do you, just as much, I respectfully submit. You will tend to sort of regard Peter as relatively less authoritative, just as I will tend to view him as more so. And so we observe that in our respective arguments. All the more necessity to exegete the actual texts more deeply . . .

*

But (it may surprise you to learn, though it shouldn’t), I have argued (in an article for National Catholic Register) that the Jerusalem Council was quite democratic and almost egalitarian (thus more “Eastern” and not at all “ultramontanist”) in the way in which it reached its conclusion:

*

[T]he Jerusalem council presents “apostles” and “elders” in conjunction six times:*

Acts 15:2 . . . Paul and Barnabas and some of the others were appointed to go up to Jerusalem to the apostles and the elders about this question.Acts 15:4 When they came to Jerusalem, they were welcomed by the church and the apostles and the elders, . . .Acts 15:6 The apostles and the elders were gathered together to consider this matter.Acts 15:22 Then it seemed good to the apostles and the elders, with the whole church, . . .Acts 15:23. . . “The brethren, both the apostles and the elders, to the brethren who are of the Gentiles in Antioch and Syria and Cili’cia, . . .Acts 16:4 . . . they delivered to them for observance the decisions which had been reached by the apostles and elders who were at Jerusalem.*“Elders” here is the Greek presbuteros, which referred to a leader of a local congregation, so that Protestants think of it primarily as a “pastor”, whereas Catholics, Orthodox, and some Anglicans regard it as the equivalent of “priest.” In any event, all agree that it is a lower office in the scheme of things than an apostle: even arguably lower than a bishop (which is mentioned several times in the New Testament).*What is striking, then, is that the two offices in the Jerusalem council are presented as if there is little or no distinction between them, at least in terms of their practical authority. It’s not an airtight argument, I concede. We could, for example, say that “bishops and the pope [and non-bishop theological advisers] gathered together at the Second Vatican Council.” We know that the pope had a higher authority. It may be that apostles here had greater authority.

*But we don’t know that with certainty, from Bible passages that mention them. They seem to be presented as having in effect, “one man one vote.” They “consider” the issue “together” (15:6). It’s the same for the “decisions which had been reached” (16:4).

*

St. Peter worked within that framework, in a council presided over by James (in the sense I have agreed with), but he still provided the central rationale for the decision and in that sense exercised ultimate and universal (and “theological”) authority. He functioned as the foremost interpreter of past religious practice and beliefs (even more than St. Paul: for whom I also have a very strong bias in the overall scheme of things). He worked together with other apostles and elders, just as popes have habitually done (as I have argued many times).

*

Dom Bernard Orchard (Catholic Commentary, 1953) offers some interesting insights:

*

7. Perhaps 6 describes a private meeting, during which ‘there had been much debate’, and now St Peter announces the result to the multitude. Be that as it may, he speaks with an authority that all accept, and by re-stating his decision in the case of Cornelius, implies that the question should not have been re-opened. . . .

*19. From St James’ ‘I judge’ it has been argued that he and not St Peter had the first position, but a word cannot prevail against the context, so favourable, here, as in the rest of Ac, to the Petrine primacy. The phrase bears a very different interpretation. ‘For which cause’, in view of Simon’s action in the case of Cornelius, and of the prophecy, ‘I’, without wishing to engage others, ‘judge’, am of opinion, a usual sense of the Gk κρίνω, and one found often in Ac, ‘that the Gentile converts are not to be disquieted’. St James shows why he adheres to the decision which has already been given by Peter on the point at issue. He then puts forward a practical suggestion, which so far from being a decree of his own, is expressly attributed to the Apostles and presbyters who adopted it, 15:28; 16:4.

*

Navarre Commentary adds:

*

6–21. The hierarchical Church, consisting of the Apostles and elders or priests, now meets to study and decide whether baptized Gentiles are obliged or not to be circumcised and to keep the Old Law. This is a question of the utmost importance to the young Christian Church and the answer to it has to be absolutely correct. Under the leadership of St. Peter, the meeting deliberates at length, but it is not going to devise a new truth or new principles: all it does is, with the aid of the Holy Spirit, to provide a correct interpretation of God’s promises and commandments regarding the salvation of men and the way in which Gentiles can enter the New Israel.*

This meeting is seen as the first general council of the Church, that is, the prototype of the series of councils of which the Second Vatican Council is the most recent. Thus, the Council of Jerusalem displays the same features as the later ecumenical councils in the history of the Church: a) it is a meeting of the rulers of the entire Church, not of ministers of one particular place; b) it promulgates rules which have binding force for all Christians; c) the content of its decrees deals with faith and morals; d) its decisions are recorded in a written document — a formal proclamation to the whole Church; e) Peter presides over the assembly.*According to the Code of Canon Law (can. 338–341) ecumenical councils are assemblies — summoned and presided over by the Pope — of bishops and some others endowed with jurisdiction; decisions of these councils do not oblige unless they are confirmed and promulgated by the Pope. This assembly at Jerusalem probably took place in the year 49 or 50.*7–11. Peter’s brief but decisive contribution follows on a lengthy discussion which would have covered the arguments for and against the need for circumcision to apply to Gentile Christians. St. Luke does not give the arguments used by the Judaizing Christians (these undoubtedly were based on a literal interpretation of the compact God made with Abraham — cf. Gen 17 — and on the notion that the Law was perennial).*Once again, Peter is a decisive factor in Church unity. Not only does he draw together all the various legitimate views of those trying to reach the truth on this occasion: he points out where the truth lies. Relying on his personal experience (what God directed him to do in connexion with the baptism of Cornelius: cf. chap. 10), Peter sums up the discussion and offers a solution which coincides with St. Paul’s view of the matter: it is grace and not the Law that saves, and therefore circumcision and the Law itself have been superseded by faith in Jesus Christ. Peter’s argument is not based on the severity of the Old Law or the practical difficulties Jews experience in keeping it; his key point is that the Law of Moses has become irrelevant; now that the Gospel has been proclaimed the Law is not necessary for salvation: he does not accept that it is necessary to obey the Law in order to be saved. Whether one can or should keep the Law for other reasons is a different and secondary matter. . . .*

[16:4] 4. The text suggests that all Christians accepted the decisions of the Council of Jerusalem in a spirit of obedience and joy. They saw them as being handed down by the Church through the Apostles and as providing a satisfactory solution to a delicate problem. The disciples accept these commandments with internal and external assent: by putting them into practice they showed their docility. Everything which a lawful council lays down merits and demands acceptance by Christians, because it reflects, as the Council of Trent teaches, “the true and saving doctrine which Christ taught, the Apostles then handed on, and the Catholic Church, under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, ever maintains; therefore, no one should subsequently dare to believe, preach or teach anything different” (De iustificatione, preface).

*

Scott Hahn (Ignatius Catholic Study Bible) observed:

*

15:11 . . . Peter speaks as the head and spokesman of the apostolic Church. He formulates a *doctrinal* judgment about the means of salvation, whereas James takes the floor after him to suggest a *pastoral* plan for inculturating the gospel in mixed communities where Jewish and Gentile believers live side by side (15:13-21).

*

And St. John Chrysostom:

*

This (James) was bishop, as they say, and therefore he speaks last, and herein is fulfilled that saying, “In the mouth of two or three witnesses shall every word be established.” (Deuteronomy 17:6; Matthew 18:16.) But observe the discretion shown by him also, in making his argument good from the prophets, both new and old. For he had no acts of his own to declare, as Peter had and Paul. And indeed it is wisely ordered that this (the active) part is assigned to those, as not intended to be locally fixed in Jerusalem, whereas (James) here, who performs the part of teacher, is no way responsible for what has been done, while however he is not divided from them in opinion. . . .*

Peter indeed spoke more strongly, but James here more mildly: for thus it behooves one in high authority, to leave what is unpleasant for others to say, while he himself appears in the milder part.

*

It occurred to me that Pope St. John Paul II didn’t actually state [using the word] that James “presided” at the council of Jerusalem in Ut Unum Sint #97. I grant that it’s possible to interpret it that way, but in the next sentence after what you cite, he wrote:

*

Do not many of those involved in ecumenism today feel a need for such a ministry? A ministry which presides in truth and love so that the ship—that beautiful symbol which the World Council of Churches has chosen as its emblem— will not be buffeted by the storms and will one day reach its haven.

*

Note that when he refers to “presides” he is referring to Peter, not James. This is obvious in the immediate context and in the larger context of the entire encyclical, since the previous section (88-96) is entitled, “The ministry of unity of the Bishop of Rome” and even the title of the section cited is called “The communion of all particular Churches with the Church of Rome: a necessary condition for unity.”

*

All that was said about James was that Peter was “respecting the authority of James, the head of the Church in Jerusalem.” So the question is: what does this mean? As I said, I think “James presided over the council” is a plausible take, but if so, I think it has to be qualified, per my overall argumentation. And could not one say that you might be reading too much into that, because of your prior bias (as we all have biases)?

*

I will be looking to see if I can find anything in JPII or Benedict XVI elsewhere dealing with this specific question of “who presided?” and/or whether James “presiding” has a particular sense. If I find that JPII said elsewhere that Peter presided, then it seems to me that Ut Unum Sint has to be interpreted in that light.

*

The presiding referenced in the subsequent paragraph pertains to his presidency over the whole Church, not to the council specifically. It is in the context of the council that he makes specific reference to respecting James’ authority.

*

Yeah, I know. I was just pointing out that when he used the word “presides” it referred to Peter, not James; and you agree. I was simply talking about that word. He never wrote, “James presided . . . ” or some such. “Respecting the authority of James” could mean “respected his authority to speak last” or “to ‘run’ a council held in his See” or any number of things. We don’t know for sure. I haven’t been able to find anything else in searches, to make it more clear. I wish I could. “The Holy See” search engine is lousy and frustrating to use.

*

Related Reading

*

Jerusalem Council vs. Sola Scriptura [9-2-04]

*

*

*

Apostolic Succession as Seen in the Jerusalem Council [National Catholic Register, 1-15-17]

*

C. S. Lewis vs. St. Paul on Future Binding Church Authority [National Catholic Register, 1-22-17]

*

*

*

*

*

Were the Jerusalem Council Decrees Universally Binding? [National Catholic Register, 12-4-19]

*

Which Has More Authority: A Pope or an Ecumenical Council? [National Catholic Register, 5-19-21]

*

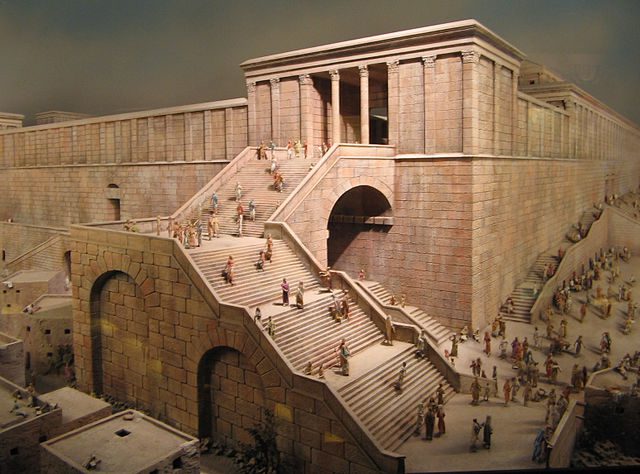

Photo credit: Reconstruction of Herod’s Temple (at the time of Jesus), with Robinson’s Arch in the foreground [Wikimedia Commons / Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.5 Generic license]

*

Summary: Meaty dialogue on the Jerusalem Council (Acts 15): specifically about who presided over it: Peter or James? Also, the question of its being a prototype of ecumenical councils is discussed.

*