This is one of a series of my reviews of the book by prominent Catholic journalist, editor, and author Philip Lawler, entitled Lost Shepherd: How Pope Francis is Misleading His Flock (due to be released on 26 February 2018). Phil was kind enough to send me a review copy, and he and others have encouraged me to read the book and review it. Their wish is granted!

For background, see my paper, On Rebuking Popes & Catholic Obedience to Popes, and three posts concerning a few statements from the book that I found very troubling and questionable, including dialogues with both Karl Keating (who positively reviewed it) and briefly with author Phil himself (one / two / three).

Previous Installments:

#4 Communion / Buenos Aires Letter

***

Phil Lawler goes after yet another of the pope’s homilies in his Chapter Seven, pp. 154-155:

In a memorable homily delivered in May 2017, Francis argued that an excessive concern with doctrine is a sign of ideology rather than faith. Reflecting on the day’s Scripture reading from the Acts of the Apostles, which recounted the debate over enforcing Mosaic Law on Gentile Christians, the pope said that the “liberty of the Spirit” led the disciples to an accord. The dispute, however, he said was caused by “jealousies, power struggles, a certain deviousness that wanted to profit from and to buy power,” temptations against which the Church must always guard.

The disciples who insisted on the enforcement of Mosaic Law, the pope said, were “fanatics.” They “were not believers; they were ideologized.” Thus he appeared to suggest that the early Church leaders who disagreed with St. Paul on the enforcement of Mosaic Law— including St. James and, before the Council of Jerusalem, which settled the question, even St. Peter himself—“were not believers.” The Scriptural account of that council offers no evidence that those on opposite sides of the question rendered harsh judgments of one other. They met, argued vigorously over a point that was not yet clear, and with the help of the Holy Spirit reached a decision that resolved their differences. Francis acknowledged that it is “a duty of the Church to clarify doctrine,” as the apostles did at the Council of Jerusalem. But he did not acknowledge that his critics within the hierarchy were calling for precisely the same sort of clarification with respect to papal teaching on marriage and the Eucharist.

Alright. Let’s take a closer look at the homily and the scriptural passages the Holy Father was commenting upon. Lawler loves clarity. I’m happy — delighted — to do my part in helping him achieve more of that (where the pope is concerned). Here he has temporarily gotten away from gossipy discussions of “palace intrigue” and internal Vatican politics that take up much of his book (which, personally, I have less than no interest in) and gotten down to a theological issue that can actually be objectively examined.

And as usual (like so many papal critics) he puts quite the obligatory cynical slant on a homily where I (for what it’s worth) see nothing whatsoever contrary to Scripture or good Catholic piety. But it seems that the critics invariably see what they want to see and it just so happens to so often come out as supposedly scandalous and objectionable.

The homily in question was preached on 5-19-17 and is preserved at the Vatican Radio site. Lawler characterizes the pope’s thoughts as “Francis argued that an excessive concern with doctrine is a sign of ideology rather than faith.” I don’t see this at all in the homily. Lawler spins it as if the pope is somehow hostile to serious doctrinal discussion or examination: as if that is a bad thing, and hence, he dismisses such as mere “ideology.” These notions are not in the homily, folks (sorry, Phil!). The homily is accurately summarized at the top as: “True doctrine unites; ideology divides.” Perfectly true and uncontroversial . . . Pope Francis states:

It was at the heart of the “first Council” of the Church: the Holy Spirit and they, the Pope with the Bishops, all together,” gathered together in order “to clarify the doctrine;” and later, through the centuries – as at Ephesus or at Vatican II – because “it is a duty of the Church to clarify the doctrine,” so that “what Jesus said in the Gospels, what is the Spirit of the Gospels, would be understood well . . . this is the problem: when the doctrine of the Church, that which comes from the Gospel, that which the Holy Spirit inspires – because Jesus said, ‘He will teach us and remind you of all that I have taught’ – [when] that doctrine becomes an ideology. And this is the great error of those people.”

He’s not saying that “excessive concern with doctrine is ideology.” That’s a wholesale distortion. He’s saying that on the one hand there is true doctrine, determined by the Church, and on the other, the distortion or corruption of the true doctrine, which becomes mere “ideology.” This is essentially the same distinction that Cardinal Newman draws in his famous comparisons of true developments of doctrine vs. heretical corruptions, and how Scripture differentiates between good, apostolic tradition and bad “traditions of men.” Why can’t Lawler grasp these rather elementary distinctions? Well, you tell me (if you can figure it out).

For my part, I think it is likely one of innumerable instances where intelligent, qualified people let their passions of one sort or another, cloud their judgment and logic in ways where it normally would be clear and logical. No one is so blind as one who will not see. It happens all the time. I critique it all the time, in my capacity as an apologist. And that’s what I see here, because this homily is not difficult to understand, and there is nothing wrong with it whatsoever. The pope reiterates his clear comparison between the good thing and the bad thing at the end:

The Church, he concluded, has “its proper Magisterium, the Magisterium of the Pope, of the Bishops, of the Councils,” and we must go along the path “that comes from the preaching of Jesus, and from the teaching and assistance of the Holy Spirit,” which is “always open, always free,” because “doctrine unites, the Councils unite the Christian community, while, on the other hand, “ideology divides.”

See what he’s saying? It’s not (Phil’s take): “too much consideration of doctrine is bad!” It is, rather: “doctrine is good and unitive; mere ideology is bad and divisive.” It’s shameful to distort (unconsciously or not) a pope’s words and alleged thoughts like this.

If Lawler had actually cited the pope’s words at any length, readers could actually see what he meant. But instead, we get the cynical summaries. He tries to “frame” how his readers think, rather than letting them think and discern for themselves. He spoon-feeds them carefully selected aspects and phrases, that end up distorted. This is the “propagandistic” approach. One tires of this!

If someone wants to bring up some homily of the Holy Father, and object to it, let the people read it for themselves! He gives no specific date or link. I provide the date and a link, and very considerable excerpts. My readers can go read the homily (or read most of it here) and make up their own minds about whether my interpretation is accurate (or if Phil’s is). I believe that the truth always wins in the end and that knowledge is power.

In his breathtakingly erroneous analysis, Lawler claims that the pope was preaching (and believes) that “The disciples who insisted on the enforcement of Mosaic Law, . . . were ‘fanatics.’ They ‘were not believers; they were ideologized.’ ” Note the internal logic here: he is literally claiming that the pope thinks some disciples were “fanatics” and not “believers” at all (!!!). And this, in a book, one of the central themes of which is that the pope is consistently unclear and incoherent: a dim guide at best. I always appreciate irony.

Now, let’s see what the biblical passage says in the first place. In the passage about the Jerusalem Council itself, “apostles and elders” are referred to, not “disciples.” The text (RSV) refers to “some men” (not “disciples”) who disputed with Paul and Barnabas before the council:

Acts 15:1-2 But some men came down from Judea and were teaching the brethren, “Unless you are circumcised according to the custom of Moses, you cannot be saved.” [2] And when Paul and Barnabas had no small dissension and debate with them, Paul and Barnabas and some of the others were appointed to go up to Jerusalem to the apostles and the elders about this question.

Then during the council we see this one line:

Acts 15:5 But some believers who belonged to the party of the Pharisees rose up, and said, “It is necessary to circumcise them, and to charge them to keep the law of Moses.”

The word “disciples” never appears in the homily: at least not in this summary of it that appears to be the one Lawler referenced. Acts 15:1 doesn’t even make clear whether those teaching this legalism are Christians. 15:5 refers to “believers.” We only have these little tidbits, so they could possibly be different groups, teaching (perhaps) somewhat different things. The second group was participating in the council, after all, so it is implied that they were at least elders. It’s irrelevant that they called themselves Pharisees. Paul did that, too, and Jesus followed their ritual customs.

The pope seems to reference not only this group of “Judaizers” but the entire group of those who opposed early Church teaching. He often digresses in his talks, to make a larger “footnoted” point. I’m very familiar with such a technique, because I do it a lot, myself, and sometimes people don’t understand my meaning or reference point. The pope does specifically differentiate the apostles from others who disagree (my italics):

The group of the apostles who want to discuss the problem, and the others who go and create problems. They divide, they divide the Church, they say that what the Apostles preached is not what Jesus said, that it is not the truth. . . .

These individuals, the Pope explained, “were not believers, they were ideologized,” they had an ideology that closed the heart to the work of the Holy Spirit. The Apostles, on the other hand, certainly discussed things forcefully, but they were not ideologized: “They had hearts open to what the Holy Spirit said. And after the discussion ‘it seemed good to the Holy Spirit and to us.’”

As for the Judaizers themselves, respectable biblical scholars disagree amongst themselves whether they were Christians or not. Some of the most eminent ones, like F. F. Bruce, don’t even take a stand for one view or the other. If the pope took one view or another on that question it would be inconsequential and well within the thought of existing scholarship. But it’s just as likely that he is referring to the dissenters described in Acts 15:1-2, and/or generally to the much larger group who dissent from Christian teachings. But he never says that “disciples” are “fanatics” and “not believers” and “ideologized.” Lawler, however, then decides to descend into yet more absurd speculations:

[H]e appeared to suggest that the early Church leaders who disagreed with St. Paul on the enforcement of Mosaic Law— including St. James and, before the Council of Jerusalem, which settled the question, even St. Peter himself—“were not believers.”

Huh? WOW!! It’s beyond my comprehension that a learned Catholic man could include (not as some kind of joke) something so utterly ridiculous in a published book, and not only that: attribute the hyper-absurd opinion to the Holy Father, with no basis whatsoever for doing so. This exhibits a level of illogic and sloppiness (not even to mention, lack of rudimentary Christian charity) that I have rarely seen (and I’ve been around the block many times).

How he arrived at this opinion (assuming he actually would claim to have some reason for it) is anyone’s guess. It’s certainly not expressed in the homily. Anyone can go read it at the link I provide above and see that for themselves. The homily never mentions James or Peter. Lawler somehow nevertheless deduces that Pope Francis thinks as follows:

1) There were arguments at the council;

2) St. James was there, so he must have disagreed with St. Paul;

3) Therefore St. James is not a “believer.”

4) St. Peter isn’t a believer either, because (before the council) he, too, clashed with St. Paul [who accused him of hypocrisy, not doctrinal error, readers may recall].

Oh boy. I have to really restrain myself at this point. This kind of nonsense is truly its own refutation, so I need not refute it, anyway. Suffice it to say that Paul and Peter never disagreed on Gentiles being received into the Church. It was St. Peter, after all, to whom God first revealed his plans for that. As I read the homily, the pope sure seems to be speaking about heretics in general, not just those (believers or no) who held that Gentile Christians had to observe the entire Mosaic Law.

Nor is there any basis in Scripture to conclude that Paul and James had any fundamental disagreement on this score. From what we know (the account of Acts 15): all three were in perfect agreement (see also Galatians 2:1-9). The Catholic Encyclopedia (“Judaizers”) backs up what I’m saying about Paul and Peter:

This incident [of Paul rebuking Peter] has been made much of by Baur and his school as showing the existence of two primitive forms of Christianity, Petrinism and Paulinism, at war with each other. But anyone, who will look at the facts without preconceived theory, must see that between Peter and Paul there was no difference in principles, but merely a difference as to the practical conduct to be followed under the circumstances. . . . That Peter’s principles were the same as those of Paul, is shown by his conduct at the time of Cornelius’s conversion, by the position he took at the council of Jerusalem, and by his manner of living prior to the arrival of the Judaizers. Paul, on the other hand, not only did not object to the observance of the Mosaic Law, as long as it did not interfere with the liberty of the Gentiles, but he conformed to its prescriptions when occasion required (1 Corinthians 9:20). Thus he shortly after circumcised Timothy (Acts 16:1-3), and he was in the very act of observing the Mosaic ritual when he was arrested at Jerusalem (Acts 21:26 sqq.).

And the pope says nothing different in this homily. He says:

“But there were always people who without any commission go out to disturb the Christian community with speeches that upset souls: ‘Eh, no, someone who says that is a heretic, you can’t say this, or that; this is the doctrine of the Church.’ And they are fanatics of things that are not clear, like those fanatics who go there sowing weeds in order to divide the Christian community. . . .

No one in their wildest dreams, in any imaginable universe, can get out of this homily, that the pope was including St. James and St. Peter in the negative descriptions, let alone pitting Paul against both of them. They absolutely could not be part of those “fanatics”, according to what the pope said shortly after, because they were apostles, and the pope referred to that august group as follows:

The Apostles, on the other hand, certainly discussed things forcefully, but they were not ideologized: “They had hearts open to what the Holy Spirit said. And after the discussion ‘it seemed good to the Holy Spirit and to us.’”

I suppose Lawler could “argue” next that Pope Francis denies that James and Peter were apostles, too. After all, anything goes in his mind, at this point. If he thinks the pope denies that they are Christian believers, then not being apostles would follow as a matter of course. One claim is as ludicrous as the other.

Case closed. I’d like to see someone defend this shoddy pseudo-“research” of Phil’s. It’s truly (no exaggeration at all!) some of the worst I’ve ever seen in 35 years of Christian / Catholic apologetics and intense Bible study. And remember, he’s accusing the pope (the “lost shepherd” who is “misleading his flock”) of having these views, that he — by some utterly inexplicable and mysterious chain of “reasoning” — invented in his own head.

***

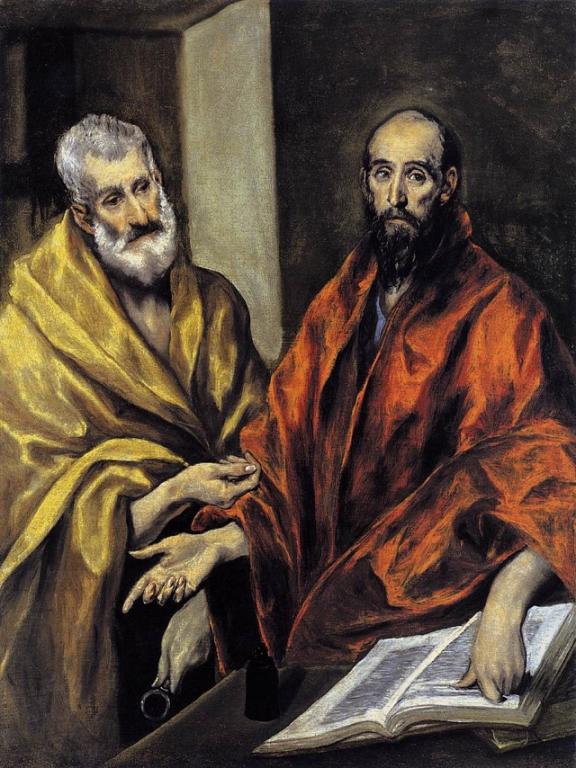

Photo credit: Saints Peter and Paul (c. 1608), by El Greco (1541-1614) [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

***