The wicked reign of King Ahab and Queen Jezebel is summarized in the Bible as follows:

1 Kings 16:29-33 (RSV) In the thirty-eighth year of Asa king of Judah, Ahab the son of Omri began to reign over Israel, and Ahab the son of Omri reigned over Israel in Samaria twenty-two years. And Ahab the son of Omri did evil in the sight of the LORD more than all that were before him. And as if it had been a light thing for him to walk in the sins of Jeroboam the son of Nebat, he took for wife Jezebel the daughter of Ethbaal king of the Sidonians, and went and served Baal, and worshiped him. He erected an altar for Baal in the house of Baal, which he built in Samaria. And Ahab made an Asherah. Ahab did more to provoke the LORD, the God of Israel, to anger than all the ki29, 32.ngs of Israel who were before him.

As to the chronology of the kings of Judah and Israel in relation to extrabiblical sources, Egyptologist and archaeologist Kenneth Kitchen writes,

We find in Kings a very remarkably preserved royal chronology, mainly very accurate in fine detail, that agrees very closely with the dates given by Mesopotamian and other sources. . . . It cannot well be the free creation of some much later writer’s imagination that just happens (miraculously!) to coincide almost throughout with the data then preserved only in documents buried inaccessibly in the ruin mounds of Assyrian cities long since abandoned and largely lost to view. (1)

Utilizing his extraordinary knowledge of such matters, Kitchen estimates the reign of King Ahab (the “twenty-two years” of 1 Kings 16:29) to be 875 or 874 to 853 B.C. (2) We have external, extrabiblical evidence that Ahab was the king of Israel in 853 B.C.:

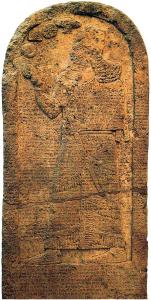

In 853 BC, the Assyrian king, Shalmaneser III fought against a coalition of western kings near at Qarqar in modern-day Syria. He left a description of the battle on a stele that was discovered in 1861 at Kurkh, near the Tigris river in Turkey. In the inscription on the Kurkh Monolith, he names “Ahab the Israelite” as one of the combatants and claims that he had one of the strongest forces, with 2000 chariots and 10000 soldiers. . . .

While neither Shalmaneser III, nor the Battle of Qarqar are mentioned in the Bible, this inscription is still important for several reasons. First, it is a clear confirmation of Ahab as a king of Israel. Secondly, it testifies to the wealth and power of the Israelite kingdom at the time. Finally, it references a historical event that can be dated. (3)

Expert on biblical chronology Edwin Thiele elaborates,

Shalmaneser also mentions that he received tribute from Jehu during his expedition to the west in his eighteenth year. This would be in the eponymy of Adam-rimani (841). Thus Jehu was already reigning over Israel sometime in 841….the interval between the death of Ahab and the accession of Jehu is exactly twelve years, being made up of the reigns of Ahaziah ,the son and successor of Ahab, and Joram, who was slain and succeeded by Jehu [2 Kings 2:51 & 3:1]….Since the interval between the battle of Qarqar, at which Ahab fought in 853, and the time Jehu paid tribute to Shalmaneser in 841 is also for a period of just twelve years, it is in this period that the reigns of Ahaziah and Joram must have taken place, with 853 as the last year of Ahab and 841 for Jehu’s accession. (4)

1 Kings 22:39 Now the rest of the acts of Ahab, and all that he did, and the ivory house which he built, and all the cities that he built, are they not written in the Book of the Chronicles of the Kings of Israel?

Bryan Windle comments on this:

Scholars have speculated that one of the enhancements which Ahab made to the capital of Samaria was to adorn the palace walls and furniture with ivory decorations such that it became known as “the Ivory House.” When Kathleen Kenyon’s team excavated Samaria in 1932, they unearthed a large collection of carved ivories dating to the Iron Age. . . . Because they date to the time of King Ahab, and were discovered near the palace complex, most scholars believe they come from the fabled, Ivory House. (5)

See an example of one of the figures. (6)

Dr. Liat Naeh (7) wrote her dissertation for the Archaeology Institute of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, on ritual artifacts made of bone and ivory dating from the Middle to Late Bronze Ages in the Levant. Bible History Daily notes her work in relation to our subject:

Naeh reviews recent wood, bone and ivory finds from the sites of Jerusalem, Rehov and Hazor in Israel to shed light on the Samaria ivories. These discoveries suggest that there was a local tradition of wood, bone and ivory carving of inlays (decorative materials inserted in something else), featuring recurring themes, during both the Bronze and Iron Ages in the southern Levant. The early interpretation of categorizing the Samaria ivories as Phoenician has impacted the subsequent discovery of other southern Levantine ivory artifacts. The bias to associate any such ivory find with the Phoenicians has caused the region’s local ivory tradition to be overlooked. Naeh suggests that it is necessary to change our view of the Samaria ivories—and ivories found throughout the southern Levant—as being made by the hands of foreigners. (8)

Bryant Wood recounts further archaeological corroboration of Ahab and the activities during his reign:

Excavations at Samaria have laid bare Ahab’s palace. An earlier palace was built on the acropolis by Ahab’s father Omri (1 Kgs 16:24). It was surrounded by a wall 5 ft thick. The royal quarter was later expanded by building a casemate (hollow) wall 32 ft wide outside the earlier wall. This is believed to be the work of Ahab. Within the compound was a building dubbed ‘the ivory house’ where many fragments of carved ivory plaques were found (see cover). This represents the most important collection of miniature art from the kingdom period found in Israel. The ivories appear to be remains of inlay originally placed on furniture in the palace of Ahab and later Israelite kings. Another interesting feature found in the royal compound was a pool in the northwest corner which could possibly be the pool referred to in Scripture where Ahab’s chariot was washed [1 Kings 22:38].

Ahab is credited with fortifying a number of cities in his kingdom (1 Kgs 22:39). At Megiddo, Stratum IVA has been attributed to this king. There were a number of prominent structures associated with Stratum IVA, including an offset-inset fortification wall 12 ft wide, large pillared buildings, a palace, and a water system which included a 260 ft long tunnel. At Hazor, Stratum VIII is dated to the time of Ahab. As at Megiddo, the city was totally rebuilt at this time. A solid fortification wall 10 ft wide was constructed, along with a citadel, a large pillared building, and an underground water system. At Tel Dan, a well-preserved city gate was constructed in the days of Ahab in Stratum III. The high place, originally constructed by Jeroboam I (1 Kgs 12:28-30) and destroyed by Ben-Hadad king of Aram (1 Kgs 15:20), was reconstructed at this time. (9)

With regard to archaeological evidence for Queen Jezebel, Bryant Wood sums up (10):

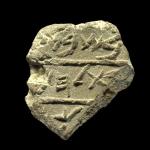

In the early 1960s a seal was purchased on the antiquities market and donated to the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. The late Nahman Avigad [my link], a leading Israeli paleographer (one who studies ancient writing), published an article about the seal in 1964 (11). He suggested the name on the seal was possibly Jezebel, but there was a problem — the first letter of the name was missing. And so, little attention was paid to the seal and it languished in the Israel Museum for decades. Then, Dutch researcher Marjo Korpel (Associate Professor of Old Testament, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands) became interested in it (12) . Korpel was first drawn to the seal because of its imagery, but then became intrigued with the inscription. She noticed that a piece had broken off at the top and this could very well have been where the missing letter was originally located. She conjectured that there were initially two letters in the area of the break: a Hebrew lamed, or L, which stood for “(belonging) to” or “for,” and the missing first letter of Jezebel’s name.

Apart from the inscription, there are other compelling reasons for identifying the seal as that of Jezebel. First, as Avigad observed, it is very fancy, suggestive of royalty. It is made of the gemstone opal and is larger than average, being 1.24 in (31 mm) from top to bottom (13). Secondly, the form of the letters is Phoenician, or imitates Phoenician writing (14). Thirdly, the seal is filled with common Egyptian symbols that were often used in Phoenicia in the ninth century BC and are suggestive of a queen. At the top is a crouching winged sphinx with a woman’s face, the body of a lioness and a female lsis/Hathor crown. To the left is an Egyptian ankh, the sign of life. In the lower register, below a winged disk, is an Egyptian-style falcon, symbol of royalty in Egypt. On either side of the falcon is a uraeus, the cobra representation of Egyptian royalty worn on crowns. At the bottom left is a lotus, a symbol often associated with royal women. All of these icons taken together denote female royalty (15).

Although 100% certainty cannot be attained, Korpel’s assessment of the evidence leads her to conclude, “I believe it is very likely that we have here the seal of the famous Queen Jezebel” (16).

Moreover, King Ahab is mentioned in the Mesha Stele (aka Moabite Stone) (17), dated to c. 840 B.C.: only about thirteen years after Ahab’s estimated year of death. It’s a Canaanite inscription under the name of King Mesha of Moab (in current-day Jordan).

All of this adds up to the conclusion that the Old Testament (as has been proven again and again) is minutely, extraordinarily accurate, even about fine details and dates of events.

FOOTNOTES

1) Kenneth A. Kitchen, On the Reliability of the Old Testament (Grand Rapids, Michigan, Eerdmans Pub. Co., 2003), 29, 32.

2) Ibid., 30.

3) Bryan Windle, “King Ahab: An Archaeological Biography,” Bible Archaeology Report, May 15, 2020.

4) Edwin R. Thiele, The Mysterious Numbers of the Hebrew Kings (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan Publishing House, 1983), 76.

5) Windle, ibid.

6) Furniture inlay: striding sphinx, Samaria, Iron Age II, ninth-eighth century B.C. (Israel Antiquities Authority); https://web.archive.org/web/20210927000927/https://www.imj.org.il/en/collections/365181.

7) Liat Naeh, Curriculum Vitae.

8) “The Samaria Ivories—Phoenician or Israelite?,” Bible History Daily / Biblical Archaeology Society, August 28, 2017.

9) Bryant Wood, “Ahab the Israelite,” Bible and Spade, Fall 1996; reprinted at Associates for Biblical Research.

10) Bryant Wood, “Seal of Jezebel Identified,” Associates for Biblical Research, July 15, 2019. See a photo of the seal in this article.

11) Nahman Avigad, “The Seal of Jezebel,” Israel Exploration Journal (1964) 14: 274-76.

12) Marjo C.A. Korpel, “Fit for a Queen: Jezebel’s Royal Seal,” Biblical Archaeology Review (2008) 34.2: 32-37, 80.

13) Avigad, 274.

14) Korpel, 37.

15) Korpel, 36-37.

16) Korpel, 37.

17) Encyclopedia Britannica, “Moabite Stone.”

***

Photo credit: Photo: Yuber. The Kurkh Monolith of the Assyrian King Shalmaneser III that mentions “Ahab the Israelite.” [Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain]

***

Summary: I offer various archaeological evidences of the time-period and various aspects and events regarding wicked King Ahab and Queen Jezebel, in the 9th c. B.C.