Five Biblical Proofs

Charles Henry Hamilton Wright (1836-1909) was an Irish Anglican clergyman. He graduated from Trinity College, Dublin, in 1857, was the Grinfield lecturer on the Septuagint at Oxford (1893–97), vicar of Saint John’s, Liverpool (1891–98), examiner in Hebrew at the University of London (1897–99), and clerical superintendent of the Protestant Reformation Society (1898–1907). He authored a number of books, including The Intermediate State and Prayers for the Dead (1900) and the volume I will be examining, Roman Catholicism, or The Doctrines of the Church of Rome Briefly Examined in the Light of Scripture (London: The Religious Tract Society, revised 5th ed., 1926).

His words will be in blue. I use RSV for biblical citations.

***

If it were right to . . . pray to such beings, the apostles must have said something on that subject . . . (p. 178)

Oh, I totally agree, and that’s the very purpose of this article!

Nothing is said respecting the invocation of the saints in the New Testament. (p. 181)

The invocation of saints is not warranted by God’s written Word. (p. 182)

The Lutheran Defense of the Augsburg Confession also stated similarly:

Scripture does not teach the invocation of the saints, or that we are to ask the saints for aid. . . . neither a command, nor a promise, nor an example can be produced from the Scriptures concerning the invocation of saints, . . . Nothing can be produced by the adversaries against this reasoning, . . . invocation does not have a testimony from God’s Word.

Likewise, fellow Anglo-Irish clergyman and scholar Richard Frederick Littledale (1833-1890) wrote a book called Plain Reasons Against Joining the Church of Rome (London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 1881), where he stated in no uncertain terms:

The whole practice of the Invocation of Saints is founded on pure guesswork. Not one syllable can be discovered in the Old or New Testament which gives the least ground or suggestion of it; God has never been pleased to reveal it, . . . God has not chosen to make it known to us, and it is a very perilous thing to fly in the face of His holy Word . . . (pp. 31-32)

I will produce three proofs that human beings who have died are invoked in the New Testament, and a similar instance from the Old Testament, with no condemnation at all present in the texts, including one instance (#1) so undeniable and clear that no one could possibly doubt it. Wright devotes all of five-and-a-half pages to this topic, thinking he has exhaustively covered it. He exhibits scant evidence that he is acquainted with any Catholic arguments on the subject. I guess that’s why his title alludes to our doctrines being “briefly examined” in his book. At least he was upfront about that.

1) The Rich Man and Abraham in Hades

Here’s a story — right from the lips of Jesus — about someone praying or making an intercessory request of someone other than God:

Luke 16:24 And he called out, ‘Father Abraham, have mercy upon me, and send Lazarus to dip the end of his finger in water and cool my tongue; for I am in anguish in this flame.’

Abraham says no, just as God will say no to a prayer not according to His will:

Luke 16:25-26 But Abraham said, ‘Son, remember that you in your lifetime received your good things, and Laz’arus in like manner evil things; but now he is comforted here, and you are in anguish. [26] And besides all this, between us and you a great chasm has been fixed, in order that those who would pass from here to you may not be able, and none may cross from there to us.’

The rich man asks Abraham again, begging:

Luke 16:27-28 And he said, ‘Then I beg you, father, to send him to my father’s house, [28] for I have five brothers, so that he may warn them, lest they also come into this place of torment.’

Abraham refuses again, saying (16:29): “They have Moses and the prophets; let them hear them.’” So, like any good self-respecting Jew (Moses and Abraham himself both “negotiated” with God), he argues with Abraham (16:30: “No, father Abraham; but if some one goes to them from the dead, they will repent.”), and Abraham refuses again, reiterating the reason why (16:31: “If they do not hear Moses and the prophets, neither will they be convinced if some one should rise from the dead.”).

If we were not supposed to ask saints to pray for us, I think this story would be almost the very last way to make that supposed point. Abraham would simply have said, “you shouldn’t be asking me for anything; ask God!” In the same way, analogously, angels refuse worship when it is offered, because only God can be worshiped:

Revelation 19:9-10 And the angel said to me, “Write this: Blessed are those who are invited to the marriage supper of the Lamb.” And he said to me, “These are true words of God.” [10] Then I fell down at his feet to worship him, but he said to me, “You must not do that! I am a fellow servant with you and your brethren who hold the testimony of Jesus. Worship God.” . . .

Revelation 22:8-9 I John am he who heard and saw these things. And when I heard and saw them, I fell down to worship at the feet of the angel who showed them to me; [9] but he said to me, “You must not do that! I am a fellow servant with you and your brethren the prophets, and with those who keep the words of this book. Worship God.”

St. Peter did the same thing:

Acts 10:25-26 When Peter entered, Cornelius met him and fell down at his feet and worshiped him. [26] But Peter lifted him up, saying, “Stand up; I too am a man.”

So did St Paul and Barnabas:

Acts 14:11-15 And when the crowds saw what Paul had done, they lifted up their voices, saying in Lycao’nian, “The gods have come down to us in the likeness of men!” [12] Barnabas they called Zeus, and Paul, because he was the chief speaker, they called Hermes. [13] And the priest of Zeus, whose temple was in front of the city, brought oxen and garlands to the gates and wanted to offer sacrifice with the people. [14] But when the apostles Barnabas and Paul heard of it, they tore their garments and rushed out among the multitude, crying, [15] “Men, why are you doing this? We also are men, of like nature with you, and bring you good news, that you should turn from these vain things to a living God who made the heaven and the earth and the sea and all that is in them.

If the true theology is that Abraham cannot be asked an intercessory request, then Abraham would have noted this and refused to even hear it. But instead he heard the request and said no. Jesus couldn’t possibly have taught a false principle. It’s not that Abraham couldn’t intercede (if that were true, he would have said so and Jesus would have made it clear), but that he wouldn’t intercede in this instance (i.e., he refused to answer the request). Abraham doesn’t deny that he is able to potentially send Lazarus to do what was requested; he only denies that it would work (by the logic of “if they don’t respond to greater factor x, nor will they respond to lesser factor y”).

Therefore, it is assumed in the story that Abraham had the ability and authority to do so on his own. And this is all taught, remember, by our Lord Jesus. Refusing a request is not the same thing as not being able to grant the request. Otherwise, we would have to say that God is unable to answer a prayer request when He refuses one. God’s answer to prayer can always be “no”, and this doesn’t “prove” that we ought not pray to God, because He turns down requests outside of His will. We know that from these scriptural passages:

James 4:3 You ask and do not receive, because you ask wrongly, to spend it on your passions.*1 John 3:22 and we receive from him whatever we ask, because we keep his commandments and do what pleases him.*1 John 5:14 And this is the confidence which we have in him, that if we ask anything according to his will he hears us.

The passage in Luke 16 has to do with two major prior premises in the larger debate concerning intercession of the saints:

1) Is it proper to “pray” to anyone but God?

2) is it proper to ask anyone but God to not only pray for, but fulfill (i.e., have the power and ability to bring about) an intercessory request?

These are the sorts of questions concerning which the Luke 16 passage is relevant. Protestantism utterly rejects #1 and #2 above; yet Luke 16 (from Jesus) clearly teaches them. Hence lies the dilemma. It matters not if both men are dead, or where they are (Hades, in this case: Lk 16:23); the rich man still can’t do what he did, according to Protestant categories of thought and theology, which holds that no one can make such a request to anyone but God. But God is never mentioned in the entire story. He’s asking Abraham to send Lazarus to him, and then to his brothers, to prevent them from going to hell. That is very much prayer: asking for supernatural aid from those who have left the earthly life and attained sainthood and perfection, with God.

So why did Jesus teach in this fashion? Why did He teach that the rich man was asking Abraham to do things that Protestant theology would hold that only God can do? And why is the whole story about him asking Abraham for requests, rather than going directly to God and asking Him? This just isn’t how it’s supposed to be, from a Protestant perspective. All the emphases are wrong, and there are serous theological errors, committed by Jesus Himself (i.e., from the erroneous Protestant perspective). Praying to a saint is a biblical teaching: expressly from Our Lord Jesus.

One common but futile retort is to say that this is “only a parable,” and hence, supposedly can be dismissed as of no import to theology. We reply that:

1) parables are teaching tools from Jesus about not only spirituality but also theology;

2) parables — like anything else Jesus says – could not contain false theological principles, sanctioned by Jesus, and not condemned by Him. Jesus couldn’t and wouldn’t teach falsehoods, whether in a parable or not;

3) I contend that the story about the rich man, Lazarus, and Abraham is not a parable in the first place, since parables don’t include proper names, let alone names of known historical figures. Jesus isn’t telling fairy tales, but recounting actual events.

4) It isn’t introduced as a parable, which is the standard biblical “protocol”. In the same book, the phrase, “he told them a parable” occurs five times: 5:36; 6:39; 12:16; 18:1; 21:29. But in Luke 16 it doesn’t. Jesus starts out, “There was a rich man . . .” (16:19).

2) Jesus Talking to and Making a Request of the Dead Lazarus

Granted, it’s a bit of a unique scenario, but the Bible provides two instances of communicating to or “contacting” the dead, making a request of a dead person (i.e., those who supposedly can never “hear” us on earth), and also — interestingly — praying for the dead at the same time, without mediums or spiritists: initiated by the praying person. The first was done by Jesus Himself:

John 11:43-44 . . . he cried with a loud voice, “Laz’arus, come out.” [44] The dead man came out, . . .

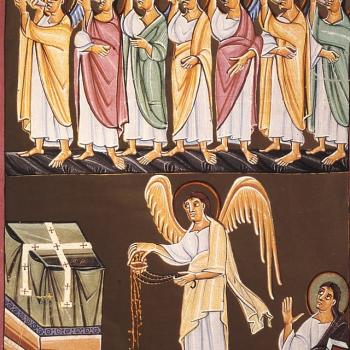

3) St. Peter Talking to and Making a Request of the Dead Tabitha

If it is objected that it was Jesus (God) talking to and raising Lazarus, so that it’s a special case not applicable to created human beings, then we have the example of St. Peter doing the same thing:

Acts 9:40-41 But Peter put them all outside and knelt down and prayed; then turning to the body he said, “Tabitha, rise.” And she opened her eyes, and when she saw Peter she sat up. [41] And he gave her his hand and lifted her up. Then calling the saints and widows he presented her alive.

We are certainly to imitate the example of the apostles (2 Thessalonians 3:9). Thus, St. Paul urges his readers to imitate him (Phil 3:17; 4:9), and both him and the Lord (1 Thessalonians 1:6-7), just he in turn imitates and follows Christ (1 Corinthians 11:1). St. Peter, and apostle and the first pope, talked to / “invoked” and made a request of a dead person; so can we.

4) The Possibility of Jesus Praying to Elijah to Save Him

Matthew 27:46-50 And about the ninth hour Jesus cried with a loud voice, “Eli, Eli, la’ma sabach-tha’ni?” that is, “My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?” [47] And some of the bystanders hearing it said, “This man is calling Eli’jah.” [48] And one of them at once ran and took a sponge, filled it with vinegar, and put it on a reed, and gave it to him to drink. [49] But the others said, “Wait, let us see whether Eli’jah will come to save him.” [50] And Jesus cried again with a loud voice and yielded up his spirit. (cf. Mk 15:34-36)

The “bystanders” at Jesus’ crucifixion assumed that He could ask (pray to) the prophet Elijah to save Him from the agony of the cross . They’re presented as allies of Jesus (not enemies), since “one of them” gave Him a drink (Mt 27:48). Matthew 27:49 shows that this type of petition was commonly believed at the time. Thus, it was believed that one could pray to one such as Elijah (who had already appeared with Jesus at the transfiguration), and that he had power to come and give aid; to “save” a person (in this case, Jesus from a horrible death).

It’s not presented as if they are wrong, and in light of other related Scriptures it is more likely that they are correct in thinking that this was a permitted scenario. Jesus, after all , had already referred to Elijah, saying that he was the prototype for John the Baptist (Mt 11:14; 17:10-13; cf. Lk 1:17 from the angel Gabriel), and it could also have been known that Elijah and Moses appeared with Jesus at the transfiguration (Mt 17:1-6; Mk 9:4; Lk 9:30-31), if these were His followers.

Some may think this is a “desperate” and utterly insignificant, inconsequential argument, but there is a lot more to it than first meets the eye. In fact, it was a well-known Old Testament tradition that the prophet Elijah would come back in some sense; alluded to several times in the New Testament:

Malachi 4:5-6 “Behold, I will send you Eli’jah the prophet before the great and terrible day of the LORD comes. [6] And he will turn the hearts of fathers to their children and the hearts of children to their fathers, lest I come and smite the land with a curse.” (cf. Mt 16:13-14; Mk 6:13-15; 8:27-28; Lk 9:7-8; 9:18-19)

All of this background being understood, it is perfectly understandable that the “bystanders” at the crucifixion misunderstood Jesus on the cross as calling out to Elijah, for this purpose. It would have been very difficult for Him to talk, and they may have been a ways away. Tradition holds that the Blessed Virgin Mary and St. John, whom we know were at the cross, were some distance away (30-40 feet). I stood on the spot when I visited Jerusalem in 2014. These other people heard Jesus say (in actuality) “Eli” or “Eloi” and mistook it for “Elijah” (“Eliyahu” or “Eliya” in Hebrew). Don Fernando on the Quora website, regarding this issue, wrote:

If Jesus was calling Elijah He would have said, ‘Eli, Eli.’ Eli in Hebrew can mean either ‘My God’ or a form of Eliyahu, Hebrew for Elijah. However, the Aramaic Eloi can only mean ‘My God.’ Mark’s has Eloi, Eloi, Lama sabakthank. Matthew does record ‘Eli, Eli’.

We know they were mistaken, and that Jesus was in fact referring to God, not Elijah. But it doesn’t affect the present argument. What is relevant to note is the fact that they casually assumed that he could call on (in effect, “pray to”) a human being rather than God. That is the argument.

In Jewish forum on stackexchange called mi yodeya, (“Do Jews pray to deceased forefathers?”), it was noted the traditional rabbinic opinion on the question was mixed, but that there is at least some indication of the practice:

I was reading in Sotah 34b and I noticed that it reads:

Raba said: It teaches that Caleb held aloof from the plan of the spies and went and prostrated himself upon the graves of the patriarchs, saying to them, ‘My fathers, pray on my behalf that I may be delivered from the plan of the spies’. . . .

For a long time there have been Jews who have indeed beseeched the dead. However, numerous sources state that this is prohibited. Some state that it is permitted if the request is not directly from the dead, but just that the dead beseech God.

Forbidden when the request is directly of the deceased

Maharam Shikk writes in a responsum (OH 293) that such practices raise both the issue of doresh el hametim (Deut. 18:11) and of serving God through an intermediary (apparently the prohibition of avoda zara; idolatry). He concludes that if one relates one’s problems to the dead hoping that they will intercede with God it is permissible, but if one wants help from them directly, it would be forbidden. He emphasises that even using them as intermediaries is forbidden according to many authorities.

Similarly, the Ben Ish Hai writes in a responsum (Rav P’alim Vol II YD 31) that it is forbidden to make requests of a dead person directly. Doing so constitutes doresh el hametim. One may only ask that the dead intercede with God. He writes this in explanation of the Zohar (Acharei Mot: 71). . . .

R. Eliezer of Metz writes in his Sefer Yereim (334-335) that the prohibition of doresh el hametim only includes involvement with the body of the deceased; involvement with the spirit of the deceased, however, would be permitted.

This argument is relatively weak, but in my opinion, it’s still worthy of consideration and not able to be immediately dismissed.

5) King Saul and the Dead Prophet Samuel

King Saul petitioned the dead prophet Samuel. All agree that consulting a medium to do so was wrong. Yet when the real Samuel appeared (the text never indicates that he is anything but real), Saul petitioned him, and Samuel didn’t condemn him for that:

1 Samuel 28:15-16 Then Samuel said to Saul, “Why have you disturbed me by bringing me up?” Saul answered, “I am in great distress; for the Philistines are warring against me, and God has turned away from me and answers me no more, either by prophets or by dreams; therefore I have summoned you to tell me what I shall do.” And Samuel said, “Why then do you ask me, since the LORD has turned from you and become your enemy?”

Samuel could properly be petitioned or, in effect, “prayed to” but he also could refuse the request, just as God does, and he did so. As Samuel explained, he didn’t question the asking as wrong and sinful, but rather, refused because the request to save Saul was against God’s expressed will: which Samuel also knew about, as a departed saint. Moreover, Samuel knew (after his death) that Saul was to be defeated in battle the next day and would die (1 Sam 28:18-19). This proves that it was truly Samuel, a prophet, and not an “impersonating demon”: who would have lied about Saul’s impending death or anything else that it uttered.

***

Once again we see — as I have seen innumerable times in 35 years of Catholic apologetics — that the Protestant anti-invocation arguments are insufficiently biblical (to put it mildly) and that the Catholic arguments are thoroughly and comprehensively biblical. It’s not “supposed” to be that way, so we are constantly told, but alas, there it is!

*

***

*

Photo credit: Healing of the Cripple and Raising of Tabitha, by Masolino da Panicale (1383-1447) [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

Summary: Five biblical examples are provided in favor of the invocation of saints: 1) rich man & Abraham, 2) Lazarus, 3) Tabitha, 4) Saul & Samuel, & 5) Jesus’ possibly calling upon Elijah.