Does “Works of the Law” Refer to All Good Works Whatsoever?

Heinrich Bullinger (1504-1575), a Calvinist leader in early Protestantism, or “reformer”, after citing Galatians 2:16, wrote the following in his most significant work, Decades (1551; rep. Cambridge University Press, 1849; first and second decades):

This is now the third time that Paul saith, that men are not justified by the works of the law: in the which clause he comprehendeth all manner of works of what sort soever. (p. 113)

John Calvin, in his Commentaries, draws the same false conclusion about Galatians 2:16:

Let it therefore remain settled, that the proposition is so framed as to admit of no exception, “that we are justified in no other way than by faith,” or, “that we are not justified but by faith,” or, which amounts to the same thing, “that we are justified by faith alone.”

Hence it appears with what silly trifling the Papists of our day dispute with us about the word, as if it had been a word of our contrivance. But Paul was unacquainted with the theology of the Papists, who declare that a man is justified by faith, and yet make a part of justification to consist in works. Of such half-justification Paul knew nothing. For, when he instructs us that we are justified by faith, because we cannot be justified by works, he takes for granted what is true, that we cannot be justified through the righteousness of Christ, unless we are poor and destitute of a righteousness of our own. Consequently, either nothing or all must be ascribed to faith or to works.

And therein lies a fundamental error, repeated by many many Protestants for over 500 years: the interpretation of a particular phrase in Paul relating to Mosaic Law, to supposedly mean all good works; thus leading to a false “faith alone” viewpoint. Recently, I proved the falsity of “faith alone” (sola fide) from a hundred passages in the Bible. But Calvin and Bullinger somehow manage to ignore that much clear teaching of the Bible. The Wikipedia article, “New Perspective on Paul” (“NPP”) provides a good overview:

The “New Perspective” movement began with the publication of the 1977 essay Paul and Palestinian Judaism by E. P. Sanders, an American New Testament scholar and Christian theologian.

Historically, the old Protestant perspective claims that Paul advocates justification through faith in Jesus Christ over justification through works of the Mosaic Law. During the Protestant Reformation, this theological principle became known as sola fide (“faith alone”); this was traditionally understood as Paul arguing that good works performed by Christians would not factor into their salvation; only their faith in Jesus Christ would save them. In this perspective, Paul dismissed 1st-century Palestinian Judaism as a sterile and legalistic religion.

According to Sanders, Paul’s letters do not address good works but instead question Jewish religious observances such as circumcision, dietary laws, and Sabbath laws, which were the “boundary markers” that set the Jews apart from other ethno-religious groups in the Levant. Sanders further argues that 1st-century Palestinian Judaism was not a “legalistic community”, nor was it oriented to “salvation by works”. As God’s “chosen people”, they were under his covenant. Contrary to Protestant belief, following the Mosaic Law was not a way of entering the covenant but of staying within it. . . .

The writings of the Apostle Paul contain a substantial amount of criticism regarding the “works of the Law“.

By contrast, “New Perspective” scholars see Paul as talking about “badges of covenant membership” or criticizing Gentile believers who had begun to rely on the Torah to reckon Jewish kinship. . . .

The “New Perspective on Paul” has, by and large, been an internal debate among Protestant biblical scholars. Many Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox scholars have responded favorably to the “New Perspective”, seeing a greater commonality with certain strands of their own traditions.

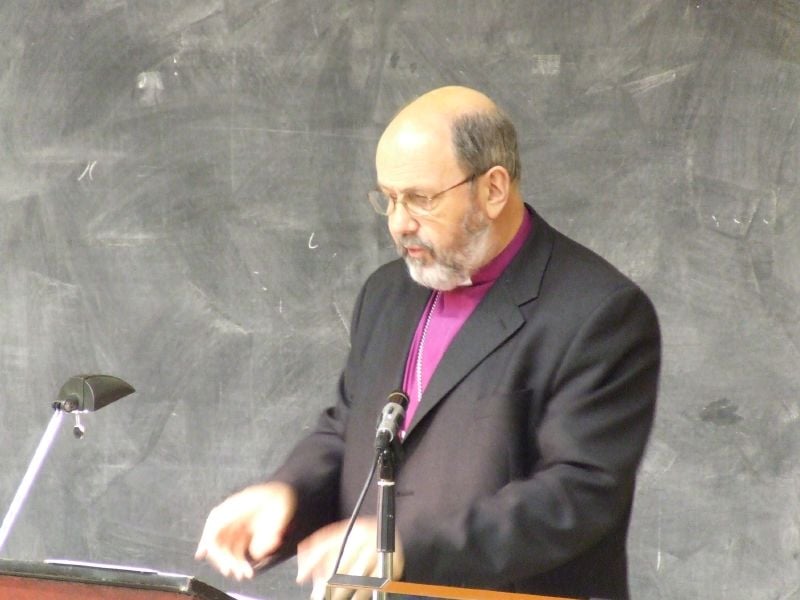

Anglican bishop and Bible scholar N. T. Wright (b. 1948) is the most well-known figure in the NPP movement. He stated in a lecture delivered at the Tenth Edinburgh Dogmatics Conference (August 2003):

In my early days of research, before Sanders had published Paul and Palestinian Judaism in 1977 and long before Dunn coined the phrase ‘The New Perspective on Paul’, I was puzzled by one exegetical issue in particular, which I here oversimplify for the sake of summary. If I read Paul in the then standard Lutheran way, Galatians made plenty of sense, but I had to fudge (as I could see dozens of writers fudging) the positive statements about the Law in Romans. If I read Paul in the Reformed way . . ., Romans made a lot of sense, but I had to fudge . . . the negative statements about the Law in Galatians. . . . it dawned on me, I think in 1976, that a different solution was possible. In Romans 10.3 Paul, writing about his fellow Jews, declares that they are ignorant of the righteousness of God, and are seeking to establish ‘their own righteousness’. The wider context, not least 9.30–33, deals with the respective positions of Jews and Gentiles within God’s purposes – and with a lot more besides, of course, but not least that. Supposing, I thought, Paul meant ‘seeking to establish their own righteousness’, not in the sense of a moral status based on the performance of Torah and the consequent accumulation of a treasury of merit, but an ethnic status based on the possession of Torah as the sign of automatic covenant membership? I saw at once that this would make excellent sense of Romans 9 and 10, and would enable the positive statements about the Law throughout Romans to be given full weight while making it clear that this kind of use of Torah, as an ethnic talisman, was an abuse. I sat up in bed that night reading through Galatians and saw that at point after point this way of looking at Paul would make much better sense of Galatians, too, than either the standard post-Luther readings or the attempted Reformed ones. . . .

I regard as absolutely basic the need to understand Paul in a way which does justice to all the letters, as well as to the key passages in individual ones) . . . the struggle to think Paul’s thoughts after him [is] a matter of obedience to scripture. . . .

When Jimmy Dunn added his stones to the growing pile I found myself in both agreement and disagreement with him. His proposal about the meaning of ‘works of the law’ in Paul – that they are not the moral works through which one gains merit but the works through which the Jew is defined over against the pagan – I regard as exactly right. It has proved itself again and again in the detailed exegesis; attempts to deny it have in my view failed. . . .

It is blindingly obvious when you read Romans and Galatians . . . that virtually whenever Paul talks about justification he does so in the context of a critique of Judaism and of the coming together of Jew and Gentile in Christ. As an exegete determined to listen to scripture rather than abstract my favourite bits from it I cannot ignore this. The only notice that most mainstream theology has taken of this context is to assume that the Jews were guilty of the kind of works-righteousness of which theologians from Augustine to Calvin and beyond have criticised their opponents; . . . I regard the New Perspective’s challenge to this point as more or less established. . . .

It seems that there has been a massive conspiracy of silence on something which was quite clear for Paul (as indeed for Jesus). Paul, in company with mainstream second-Temple Judaism, affirms that God’s final judgment will be in accordance with the entirety of a life led – in accordance, in other words, with works. He says this clearly and unambiguously in Romans 14.10–12 and 2 Corinthians 5.10. He affirms it in that terrifying passage about church-builders in 1 Corinthians 3. But the main passage in question is of course Romans 2.1–16. . . .

Here is the first statement about justification in Romans, and lo and behold it affirms justification according to works! The doers of the law, he says, will be justified (2.13). Shock, horror; Paul cannot (so many have thought) have really meant it. So the passage has been treated as a hypothetical position which Paul then undermines by showing that nobody can actually achieve it; or, by Sanders for instance, as a piece of unassimilated Jewish preaching which Paul allows to stand even though it conflicts with other things he says. But all such theories are undermined by exegesis itself, not least by observing the many small but significant threads that stitch Romans 2 into the fabric of the letter as a whole. Paul means what he says. Granted, he redefines what ‘doing the law’ really means; he does this in chapter 8, and again in chapter 10, with a codicil in chapter 13. But he makes the point most compactly in Philippians 1.6: he who began a good work in you will bring it to completion on the day of Christ Jesus. The ‘works’ in accordance with which the Christian will be vindicated on the last day are not the unaided works of the self-help moralist. Nor are they the performance of the ethnically distinctive Jewish boundary-markers (sabbath, food-laws and circumcision). They are the things which show, rather, that one is in Christ; the things which are produced in one’s life as a result of the Spirit’s indwelling and operation. . . .

I am fascinated by the way in which some of those most conscious of their reformation heritage shy away from Paul’s clear statements about future judgment according to works. It is not often enough remarked upon, for instance, that in the Thessalonian letters, and in Philippians, he looks ahead to the coming day of judgment and sees God’s favourable verdict not on the basis of the merits and death of Christ, not because like Lord Hailsham he simply casts himself on the mercy of the judge, but on the basis of his apostolic work. . . . [Paul is] clear that the things he does in the present, by moral and physical effort, will count to his credit on the last day, precisely because they are the effective signs that the Spirit of the living Christ has been at work in him. We are embarrassed about saying this kind of thing; Paul clearly is not. What on earth can have happened to a sola scriptura theology that it should find itself forced to screen out such emphatic, indeed celebratory, statements?

With that background in mind, I’d like to briefly examine the contexts of St. Paul’s use of the phrase, “works of the law.” Here are the eight instances of that phrase or “works of law” in six verses in his epistles:

Romans 3:20 For no human being will be justified in his sight by works of the law, since through the law comes knowledge of sin.

Romans 3:28 For we hold that a man is justified by faith apart from works of law. (also, “works” in 3:27 seems to be in the same sense, based on the context of 3:20, 28)

Galatians 2:16 yet who know that a man is not justified by works of the law but through faith in Jesus Christ, even we have believed in Christ Jesus, in order to be justified by faith in Christ, and not by works of the law, because by works of the law shall no one be justified.

Galatians 3:2 Let me ask you only this: Did you receive the Spirit by works of the law, or by hearing with faith?

Galatians 3:5 Does he who supplies the Spirit to you and works miracles among you do so by works of the law, or by hearing with faith?

Galatians 3:10 For all who rely on works of the law are under a curse; for it is written, “Cursed be every one who does not abide by all things written in the book of the law, and do them.”

Do the immediate contexts of these passages suggest that Paul is referring to all works — even good works — , or, on the other hand, works in the sense of Jewish religious observances such as circumcision, dietary laws, and Sabbath laws, which were the ‘boundary markers’ that set the Jews apart” (as the Wikipedia article put it)? The phrase, “works of the law” — because of the word “law” — would seem to me to suggest on its face the latter position, but as we have seen, most Protestant exegetes through the centuries have not thought so, and have followed Bullinger’s and Calvin’s thinking on the issue.

N. T. Wright thinks they have been greatly mistaken, and Catholics agree wholeheartedly with that assessment. The erroneous man-generated tradition of sola fide has overcome common sense exegesis in this instance. When Paul refers to “the law” all agree that he means by that, the Mosaic Law, given to Moses on Mt. Sinai and codified in the first five books of the Bible (the Torah or Pentateuch). Let’s now examine the contexts of these passages.

Romans 3:20

The “law” is referred to in both the immediate preceding and succeeding verses:

Romans 3:19 Now we know that whatever the law says it speaks to those who are under the law, so that every mouth may be stopped, and the whole world may be held accountable to God.

Romans 3:21 But now the righteousness of God has been manifested apart from law, although the law and the prophets bear witness to it,

Romans 3:28

The context of the next three verses refers to Jews and Gentiles, circumcision, and “the law” and Paul even makes it a point to stress that “we uphold the law.”

Romans 3:29-31 Or is God the God of Jews only? Is he not the God of Gentiles also? Yes, of Gentiles also, [30] since God is one; and he will justify the circumcised on the ground of their faith and the uncircumcised through their faith. [31] Do we then overthrow the law by this faith? By no means! On the contrary, we uphold the law.

In the next chapter, devoted to Abraham, who lived before the law, Paul still refers to “the law” five times in 4:13-16.

Galatians 2:16

Galatians 2:15 We . . . are Jews by birth . . .

Galatians 2:19-21 For I through the law died to the law, that I might live to God. . . . [21] I do not nullify the grace of God; for if justification were through the law, then Christ died to no purpose.

Galatians 3:2, 5, 10

Paul had been discussing “the law” at the end of chapter 2 (2:19-21). Then he proceeds to refer to “the law” twelve more times throughout the chapter, besides 3:2, 5, 10 (3:11-13, 17-19, 21, 23-24).

*

***

*

Photo credit: N. T. Wright (20 December 2007), by Gareth Saunders [Wikimedia Commons / Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license]

Summary: The New Perspective on Paul — in agreement with Catholics — holds that Pauline “works of the law” are “boundary markers” that set the Jews apart from other religious groups.