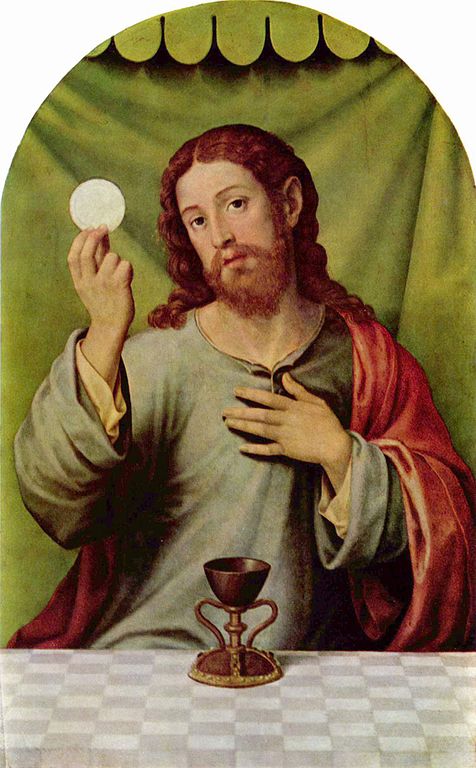

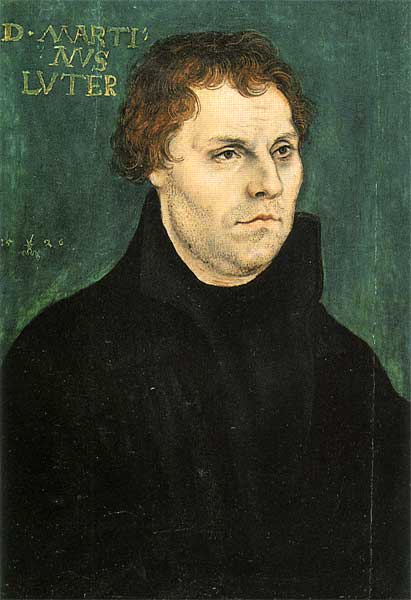

Reformed Protestant (or Reformed Catholic; take your pick) Kevin D. Johnson has been making the argument that these two men have a similar theology regarding the Holy Eucharist. He wrote in his blog entry, “The Catholic Nature of Calvin’s View of the Real Presence” (blue-colored emphases added):

For Calvin, his view of the Real Presence very much agreed with Cyril of Jerusalem and a better term to understand him is the “mystical presence” of Christ . . . The term “spiritual presence” can be misleading because Calvin’s opponents (both Lutheran and Roman Catholic) tried to emphasize a presence that avoided the fuller definition given above and claim that he believed that Christ was only present in spirit and not bodily. Christ’s bodily–physical–presence was there in the sacrament according to Calvin, but this was so by the Spirit (hence the usage of the term “spiritual” which refers to the Holy Spirit making this presence possible). This is in line with the orthodox catholic teaching of the subject over the ages–and Calvin very much resonated with the Church in this regard. It is wrong to think somehow that he broke with catholic tradition here.

. . . I think Roman Catholics must admit that at the very least, transubstantiation as it was approved at the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215 and Trent in the mid-sixteenth century was a later development of the doctrines both of the Real Presence and the Lord’s Supper and while it is certainly a part of Roman Catholic orthodoxy now it was not so clear cut prior to 1215 when it was made a part of the deposit of the faith. Indeed, it had been hotly debated for 400 years prior to the Fourth Lateran Council starting with its chief protagonist Radbertus.

Calvin’s view actually represents an earlier tradition via Cyril of Jerusalem among others (arguably, Augustine since that is where Calvin primarily pulls his definition of a “sacrament” in his Institutes) and is truer not only to the text of Scripture but also to the orthodox theology of the Church over the ages. In addition, it avoids the heavy influence of a scholastic look at such an issue that transubstantiation clearly represents.

The scholastic theology of Rome caused a break between the orthodoxy of the early and medieval Church and while there are Roman Catholic apologists out there who can look back at the early fathers and read transubstantiation back into their statements, it is very difficult for a true scholarly effort to accomplish the same thing without admitting a great deal of prejudice in interpreting those early texts in such a manner.

Calvin and the other magisterial Reformers very clearly viewed themselves as part of the historic Catholic Church and felt that it was the hierarchy of Roman Catholicism that had departed from the ancient deposit of the faith. Regarding this issue, it is very easy to see why they felt that way once one acquaints himself with all of the historical data on the matter of the Real Presence and the development of transubstantiation as the Church approached the High Middle Ages.

This concisely summarizes Kevin’s position and gives us a solid statement of his position, that we can work with as we examine the historical data (in which alone the question can be satisfactorily and substantively settled). In his blog entry, “A Reformed Doctrine of the Eucharist and Ministry and its Implications for Roman Catholic Dialogues,” Kevin cites at length the following article by David Willis: “A Reformed Doctrine of the Eucharist and Ministry and Its Implications for Roman Catholic Dialogues”, Journal of Ecumenical Studies, 21:2, Spring 1984, pp. 295-309. Here are some highlights from his post (all from Willis, and emphases again added):

. . . Calvin maintained a doctrine of the real presence in the Lord’s Supper. The starting point for his doctrine, one which he shares with Cyril of Jerusalem, is the mystical union of Christ with believers. According to Calvin, in the eucharist we participate not just in the benefits of Christ but also in his substance, that of his humanity no less than of his divinity; Christ is substantially, not just sacramentally, present. Calvin’s objection to the doctrines of transubstantiation and bodily ubiquity is that they constitute threats to a correct doctrine of the real presence–the former by weakening the reality of the signs which Christ uses as the instruments for his presence, the latter by weakening the reality of the humanity of Christ . . .

Saying that Christ is really present by the power of the Spirit was not an adequate account of Christ’s real presence, according to those who insisted that the real presence had to be guaranteed either by a doctrine of transubstantiation or bodily ubiquity.

We may, then, summarize (using the above data) Kevin’s interpretation of Calvin’s eucharistic theology and its relation to St. Cyril of Jerusalem, in the following way:

1. Calvin’s notion of “real presence” was “very much” in agreement with St. Cyril.

2. Calvin’s understanding of “real presence” is “in line with the orthodox catholic teaching of the subject over the ages.” He did not break with catholic tradition on this point.

3. Transubstantiation was a development postdating the Fathers, and was quite questionable even strictly in terms of “Roman Catholic orthodoxy” prior to 1215.

4. The eucharistic theology of St. Cyril (reflected by Calvin) is basically at odds with transubstantiation, which is primarily a result of late medieval scholastic theology, and constituted a “break” with earlier tradition.

5. To find transubstantiation in the Fathers is “very difficult” for one engaged in a “true scholarly effort,” and requires a “great deal of prejudice” (in other words, it is anachronistic interpretation).

From these opinions, I therefore logically conclude (expressing it in a different manner which follows straightforwardly from the above):

1. If transubstantiation, or something closely approximating it, or a lesser-developed version of it, can be found in the Fathers, then Kevin’s argument collapses, since he holds that it was only a later scholastic development, and a break with the Fathers. If the development can be shown to have occurred in the patristic age, then so much the worse for Kevin’s historical scenario regarding “catholic orthodoxy” and the Eucharist.

2. If, in particular, St. Cyril of Jerusalem can be shown to adopt something akin to transubstantiation or otherwise opposed to Calvin’s opinions (e.g., acceptance of the Sacrifice of the Mass or adoration of the consecrated Host), then the strong comparison and parallel must be withdrawn as factually inaccurate. This follows from the content of #1 and #2 above. If he can be shown to have accepted a primitive form of transubstantiation, then #3 and #4 must be discarded as well.

3. If non-Catholic scholars can be produced who find transubstantiation, or something closely approximating it, or a lesser-developed version of it, in the Fathers (or in St. Cyril particularly), then we must conclude that they, too, are guilty of anachronistic interpretation, are lacking in a “true scholarly effort,” and suffer from a “great deal of prejudice” — and for no particular reason, as they are not Catholic apologists, etc., determined to shore up a [Roman] Catholic position at all costs, in the face of demonstrable facts.

Now, to begin our study, let us examine John Calvin’s opinion concerning transubstantiation, adoration of the Host, and the Sacrifice of the Mass. We will then proceed to inquire as to whether this was in accord with the Fathers and St. Cyril in particular, and thus merely continuing that earlier “orthodox tradition,” or whether it was, in fact, a break from the same (rather than transubstantiation being the decisive break and corruption of earlier doctrine). Blue-colored emphases remain my own throughout. Italics are in the originals.

TRANSUBSTANTIATION

From: Reply to Jacopo Cardinal Sadoleto

(September 1, 1539; translated by Henry Beveridge, 1844; reprinted in A Reformation Debate, edited by John C. Olin, New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1966; citation from p. 71)

In condemning your gross dogma of transubstantiation, . . . we have not acted without the concurrence of the ancient Church, under whose shadow you endeavor in vain to hide the very vile superstitions to which you are here addicted.

From: Jules Bonnet, editor, John Calvin: Selected Works of John Calvin: Tracts and Letters: Letters, Part 2, 1545-1553, volume 5 of 7; translated by David Constable; Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Book House, 1983; reproduction of Letters of John Calvin, volume II [Philadelphia: Presbyterian Board of Publication, 1858]:

. . . transubstantiation was a mere fiction . . . (Letter to Farel, 11 May 1541, p. 261)

From: The True Method of Reforming the Church and Healing Her Divisions

(1547; translated by Henry Beveridge, 1851; reprinted in Selected Works of John Calvin: Tracts and Letters, Vol. 3: Tracts, Part 3, edited by Henry Beveridge and Jules Bonnet, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Book House, 1983; citation from p. 277):

In treating of the Supper they bring back the fiction of Transubstantiation, against which all are forced to protest who are unwilling that the true use of the Supper should be lost to them. A common property of the Sacraments is, that in a manner adapted to the human intellect, they exhibit what is spiritual by a visible sign. The spiritual meaning of the Supper is, that the flesh of Christ is the meat and his blood the drink on which our souls are fed. Unless the sign correspond to this the nature of the Sacrament is destroyed. It is therefore necessary that the bread and wine be held forth to us, that from them we may learn what Christ sets before us in figure. But if the bread which we see is an empty show, what will it attest to us but an empty shadow of the flesh of Christ? They pretend that there is only an appearance of bread, which deceives the eye. How far will this phantom carry us?

ADORATION OF THE HOST

From: On Shunning the Unlawful Rites of the Ungodly, and Preserving the Purity of the Christian Religion.

(1537; translated by Henry Beveridge, 1851; reprinted in Selected Works of John Calvin: Tracts and Letters, Vol. 3: Tracts, Part 3, edited by Henry Beveridge and Jules Bonnet, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Book House, 1983; citations from pp. 383, 386-387, 393):

. . . the abominable Idolatry, when bread is pretended to assume Divinity, and raised aloft as God, and worshipped by all present! The thing is so atrocious and insulting, that without being seen it can scarcely be believed . . . A little bit of Bread, I say, is displayed, adored, and invoked. In short, it is believed to be God, a thing which even the Gentiles never believed of any of their statues! And let no one here object that it is not the Bread that is adored, but Christ who becomes substituted for the Bread the moment it has been legitimately consecrated.

. . . At last, behold the Idol (puny, indeed, in bodily appearance, and white in colour, but by far the foulest and most pestiferous of all Idols!) lifted up to affect the minds of the beholders with superstition. While all prostrate themselves in stupid amazement . . . What effrontery must ours be, if we deny that any one of the things delivered in Scripture against Idolatry is inapplicable to the Idolatry here detected and proved! What! is this Idol in any respect different from that which the Second Commandment of the Law forbids us to worship? But if it is not, why should the worship of it be regarded as less a sin than the worship of the Statue at Babylon? . . . how can it be lawful to keep rolling about in such a sink of pollution and sacrilege as here manifestly exists?

. . . Away, then, with those who, on the view of a missal-god of wafer, bend their knees in hypocritical adoration, and allege that they sin the less because they worship an idol under the name of God! As if the Lord were not doubly mocked by that nefarious use of his Name, when, in a manner abandoning Him, men run to an idol, and he himself is represented as passing into bread, because enchanted by a kind of dull and magical murmur!

From: Reply to Sadoleto (ibid., p. 71):

In . . . declaring that stupid adoration which detains the minds of men among the elements, and permits them not to rise to Christ, to be perverse and impious, we have not acted without the concurrence of the ancient Church, under whose shadow you endeavor in vain to hide the very vile superstitions to which you are here addicted.

From Bonnet, Selected Works (ibid.):

. . . the reposition of the consecrated wafer a piece of superstition, that the adoration of the wafer was idolatrous, or at the least dangerous, since it had no authority from the word of God . . . I condemned that peculiar local presence; the act of adoration I declared to be altogether insufferable. (Letter to Farel, 11 May 1541, p. 261)

From: Institutes of the Christian Religion:

(1559 ed., translation of Ford L. Battles; edited by John T. McNeill;, Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 2 volumes, 1960):

. . . fictitious transubstantiation . . . the first fabricators of this local presence could not explain how Christ’s body might be mixed with the substance of bred without many absurdities immediately cropping up . . . But it is wonderful how they fell to such a point of ignorance, even of folly, that, despising not only Scripture but even the consensus of the ancient church, they unveiled that monster . . . they all [the Fathers, or “old writers”] everywhere clearly proclaim that the Sacred Supper consists of two parts, the earthly and the heavenly; and they interpret the earthly part to be indisputably bread and wine.

Surely, whatever our opponents may prate, it is plain that to confirm this doctrine they lack the support of antiquity . . . For transubstantiation was devised not long ago; indeed, not only was it unknown to those purer ages when the purer doctrine of religion still flourished, but even when that purity already was somewhat corrupted. (IV, 17, 14)

They could never have been so foully deluded by Satan’s tricks unless they had already been bewitched by this error . . . among them consecration was virtually equivalent to magic incantation . . . Even in Bernard’s time [1090-1153], although a blunter manner of speaking had been adopted, transubstantiation was not yet recognized. (IV, 17, 15)

THE SACRIFICE OF THE MASS

From: On Shunning the Unlawful Rites of the Ungodly, and Preserving the Purity of the Christian Religion.

(1537; translated by Henry Beveridge, 1851; reprinted in Selected Works of John Calvin: Tracts and Letters, Vol. 3: Tracts, Part 3, edited by Henry Beveridge and Jules Bonnet, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Book House, 1983; citations from pp. 383, 386-388):

. . . the mere name of Sacrifice (as the priests of the Mass understand it) both utterly abolishes the cross of Christ, and overturns his sacred Supper which he consecrated as a memorial of his death. For both, as we know, is the death of Christ utterly despoiled of its glory, unless it is held to be the one only and eternal Sacrifice; and if any other Sacrifice still remains, the Supper of Christ falls at once, and is completely torn up by the roots . . .

Will it still be denied to me that he who listens to the Mass with a semblance of Religion, every time these acts are perpetrated, professes before men to be a partner in sacrilege, whatever his mind may inwardly declare to God?

. . . Taking the single expression which gives the essence of all the invectives which the Apostle had uttered against Idolatry — that we could not at once be partakers at the table of Christ and the table of demons — who can deny its applicability to the Mass? Its altar is erected by overthrowing the Table of Christ . . . In the Mass Christ is traduced, his death is mocked, an execrable idol is substituted for God — shall we hesitate, then, to call it the table of demons? Or shall we not rather, in order justly to designate its monstrous impiety, try, if possible, to devise some new term still more expressive of detestation? Indeed, I exceedingly wonder how men, not utterly blind, can hesitate for a moment to apply the name “Table of Demons” to the Mass, seeing they plainly behold in the erection and arrangement of it the tricks, engines, and troops of devils all combined . . . I have long been maintaining on the strongest grounds that Christian men ought not even to be present at it!

. . . will you represent the Supper under the image of a diabolical Mass? Will you persuade us that in an act in which you ignominiously travesty the death of the Lord, you observe his Supper, in which he distinctly exhorts us to shew forth his death?

From Reply to Sadoleto (ibid., p. 74):

. . . We are indignant, that in the room of the sacred Supper has been substituted a sacrifice, by which the death of Christ is emptied of its virtues . . . in all these points, the ancient Church is clearly on our side, and opposes you, not less than we ourselves do.

From: Institutes of the Christian Religion

(1559 edition; translated by Henry Beveridge, 1845)

Scarcely can we hold any meeting with them without polluting ourselves with open idolatry. Their principal bond of communion is undoubtedly in the Mass, which we abominate as the greatest sacrilege. (IV, 2, 9)

From: Institutes of the Christian Religion:

(1559 ed., translation of Ford L. Battles; edited by John T. McNeill;, Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 2 volumes, 1960)

The height of frightful abomination was when the devil . . . blinded nearly the whole world with a most pestilential error – the belief that the Mass is a sacrifice . . . It is most clearly proved by the Word of God that this Mass . . . inflicts signal dishonor upon Christ, buries and oppresses his cross, consigns his death to oblivion, takes away the benefit which came to us from it . . .

Let us therefore show . . . that in it an unbearable blasphemy and dishonor is inflicted upon Christ . . . they not only deprive Christ of his honor, and snatch from him the prerogative of that eternal priesthood, but try to cast him down from the right hand of his Father . . .

Another power of the Mass was set forth: that it suppresses and buries the cross and Passion of Christ. This is indeed very certain: that the cross of Christ is overthrown as soon as the altar is set up . . .

This perversity was unknown to the purer Church . . . It is very certain that the whole of antiquity is against them . . . Augustine himself in many passages interprets it as nothing but a sacrifice of praise . . . Chrysostom also speaks in the same sense . . .

But I observe that the ancient writers also misinterpreted this memorial . . . because their Supper displayed some appearance of repeated or at least renewed sacrifice . . . I cannot bring myself to condemn them for any impiety; still, I think they cannot be excused for having sinned somewhat in acting as they did. For they have followed the Jewish manner of sacrificing more closely than either Christ had ordained or the nature of the gospel allowed . . .

What remains but that the blind may see, the deaf hear, and even children understand this abomination of the Mass? . . . it . . . has so stricken them with drowsiness and dizziness, that, more stupid than brute beasts, they have steered the whole vessel of their salvation into this one deadly whirlpool. Surely, Satan never prepared a stronger engine to besiege and capture Christ’s Kingdom . . . they so defile themselves in spiritual fornication, the most abominable of all . . . The Mass . . . from root to top, swarms with every sort of impiety, blasphemy, idolatry, and sacrilege. (IV, 18, 1-3,9-11,18; from vol. II, pp. 1429-1431, 1437, 1439-1440, 1445-1446)

* * * * *

Important Protestant Church Historians Differ Radically From Calvin (and Kevin Johnson) Regarding the History of Transubstantiation, Adoration, and the Sacrifice of the Mass:

Philip Schaff, History of the Christian Church, vol. 3, A.D. 311-600, rev. 5th ed., Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans, rep. 1974, orig, 1910, 492-495 [see further primary documentation by visiting the link provided]:

The doctrine of the sacrament of the Eucharist was not a subject of theological controversy and ecclesiastical action till the time of Paschasius Radbert, in the ninth century . . . In general, this period, . . . was already very strongly inclined toward the doctrine of transubstantiation, and toward the Greek and Roman sacrifice of the mass, which are inseparable in so far as a real sacrifice requires the real presence of the victim. But the kind and mode of this presence are not yet particularly defined, and admit very different views: Christ may be conceived as really present either in and with the elements (consubstantiation, impanation), or under the illusive appearance of the changed elements (transubstantiation), or only dynamically and spiritually.

. . . I. The realistic and mystic view is represented by several fathers and the early liturgies, whose testimony we shall further cite below. They speak in enthusiastic and extravagant terms of the sacrament and sacrifice of the altar. They teach a real presence of the body and blood of Christ, which is included in the very idea of a real sacrifice, and they see in the mystical union of it with the sensible elements a sort of repetition of the incarnation of the Logos. With the act of consecration a change accordingly takes place in the elements, whereby they become vehicles and organs of the life of Christ, although by no means necessarily changed into another substance. To denote this change very strong expressions are used, like metabolhv, metabavllein, metabavllesqai, metastoiceiou’sqai, metapoiei’sqai, mutatio, translatio, transfiguratio, transformatio; illustrated by the miraculous transformation of water into wine, the assimilation of food, and the pervasive power of leaven.

Cyril of Jerusalem goes farther in this direction than any of the fathers. He plainly teaches some sort of supernatural connection between the body of Christ and the elements, though not necessarily a transubstantiation of the latter. Let us hear the principal passages. “Then follows,” he says in describing the celebration of the Eucharist, “the invocation of God, for the sending of his Spirit to make the bread the body of Christ, the wine the blood of Christ. For what the Holy Ghost touches is sanctified and transformed.” “Under the type of the bread is given to thee the body, under the type of the wine is given to thee the blood, that thou mayest be a partaker of the body and blood of Christ, and be of one body and blood with him.” “After the invocation of the Holy Ghost the bread of the Eucharist is no longer bread, but the body of Christ.” “Consider, therefore, the bread and the wine not as empty elements, for they are, according to the declaration of the Lord, the body and blood of Christ.” In support of this change Cyril refers at one time to the wedding feast at Cana, which indicates, the Roman theory of change of substance; but at another to the consecration of the chrism, wherein the substance is unchanged. He was not clear and consistent with himself. His opinion probably was, that the eucharistic elements lost by consecration not so much their earthly substance, as their earthly purpose.

Gregory of Nyssa, though in general a very faithful disciple of the spiritualistic Origen, is on this point entirely realistic. He calls the Eucharist a food of immortality, and speaks of a miraculous transformation of the nature of the elements into the glorified body of Christ by virtue of the priestly blessing . . .

Of the Latin fathers, Hilary, Ambrose, and Gaudentius († 410) come nearest to the later dogma of transubstantiation. The latter says: “The Creator and Lord of nature, who produces bread from the earth, prepares out of bread his own body, makes of wine his own blood.”

Right after this, Schaff tries his hardest to minimize all instances which strongly suggest transubstantiation (“closely as these and similar expressions verge upon the Roman doctrine of transubstantiation, they seem to contain at most a dynamic, not a substantial, change of the elements into the body and the blood of Christ”), but his scholarly fairness compels him to acknowledge that this thought was present in the Fathers. The evidence is too strong for him to deny it. Thus he is already clashing with Calvin’s historical account.

Likewise (unable to wholly hide his polemical partisanship), he minimizes adoration, but is honest enough to present instances of this teaching from four very prominent Fathers (pp. 501-502):

As to the adoration of the consecrated elements: This follows with logical necessity from the doctrine of transubstantiation, and is the sure touchstone of it . . . Chrysostom says: “The wise men adored Christ in the manger; we see him not in the manger, but on the altar, and should pay him still greater homage.” Theodoret, in the passage already cited, likewise uses the term proskuvnei’n [Greek for “worship”], but at the same time expressly asserts the continuance of the substance of the elements. Ambrose speaks once of the flesh of Christ “which we to-day adore in the mysteries,” and Augustine, of an adoration preceding the participation of the flesh of Christ.

So both transubstantiation and adoration are clearly present among the Fathers, even according to a prominent Protestant historian who completely disagrees personally with these doctrines. Calvin is simply in error. Schaff then takes up the subject of the Sacrifice of the Mass in his next section (§ 96. “The Sacrifice of the Eucharist”), and we find no absence there, either, contra Calvin’s dogmatic pontifications (pp. 503-508, 510):

The Catholic church, both Greek and Latin, sees in the Eucharist not only a sacramentum, in which God communicates a grace to believers, but at the same time, and in fact mainly, a sacrificium, in which believers really offer to God that which is represented by the sensible elements. For this view also the church fathers laid the foundation, and it must be conceded they stand in general far more on the Greek and Roman Catholic than on the Protestant side of this question.

. . . In this view certainly, in a deep symbolical and ethical sense, Christ is offered to God the Father in every believing prayer, and above all in the holy Supper; i.e. as the sole ground of our reconciliation and acceptance . . .

But this idea in process of time became adulterated with foreign elements, and transformed into the Graeco-Roman doctrine of the sacrifice of the mass. According to this doctrine the Eucharist is an unbloody repetition of the atoning sacrifice of Christ by the priesthood for the salvation of the living and the dead; so that the body of Christ is truly and literally offered every day and every hour, and upon innumerable altars at the same time. The term mass, which properly denoted the dismissal of the congregation (missio, dismissio) at the close of the general public worship, became, after the end of the fourth century, the name for the worship of the faithful, which consisted in the celebration of the eucharistic sacrifice and the communion.

. . . We pass now to the more particular history. The ante-Nicene fathers uniformly conceived the Eucharist as a thank-offering of the church; the congregation offering the consecrated elements of bread and wine, and in them itself, to God. This view is in itself perfectly innocent, but readily leads to the doctrine of the sacrifice of the mass, as soon as the elements become identified with the body and blood of Christ, and the presence of the body comes to be materialistically taken. The germs of the Roman doctrine appear in Cyprian about the middle of the third century, in connection with his high-churchly doctrine of the clerical priesthood. Sacerdotium and sacrificium are with him correlative ideas,

. . . The doctrine of the sacrifice of the mass is much further developed in the Nicene and post-Nicene fathers, though amidst many obscurities and rhetorical extravagances, and with much wavering between symbolical and grossly realistic conceptions, until in all essential points it is brought to its settlement by Gregory the Great at the close of the sixth century.

. . . 2. It is not a new sacrifice added to that of the cross, but a daily, unbloody repetition and perpetual application of that one only sacrifice. Augustine represents it, on the one hand, as a sacramentum memoriae, a symbolical commemoration of the sacrificial death of Christ; to which of course there is no objection. But, on the other hand, he calls the celebration of the communion verissimum sacrificium of the body of Christ. The church, he says, offers (immolat) to God the sacrifice of thanks in the body of Christ, from the days of the apostles through the sure succession of the bishops down to our time. But the church at the same time offers, with Christ, herself, as the body of Christ, to God. As all are one body, so also all are together the same sacrifice. According to Chrysostom the same Christ, and the whole Christ, is everywhere offered. It is not a different sacrifice from that which the High Priest formerly offered, but we offer always the same sacrifice, or rather, we perform a memorial of this sacrifice. This last clause would decidedly favor a symbolical conception, if Chrysostom in other places had not used such strong expressions as this: “When thou seest the Lord slain, and lying there, and the priest standing at the sacrifice,” or: “Christ lies slain upon the altar.”

3. The sacrifice is the anti-type of the Mosaic sacrifice, and is related to it as substance to typical shadows. It is also especially foreshadowed by Melchizedek’s unbloody offering of bread and wine. The sacrifice of Melchizedek is therefore made of great account by Hilary, Jerome, Augustine, Chrysostom, and other church fathers, on the strength of the well-known parallel in the seventh chapter of the Epistle to the Hebrews.

. . . Cyril of Jerusalem, in his fifth and last mystagogic Catechesis, which is devoted to the consideration of the eucharistic sacrifice and the liturgical service of God, gives the following description of the eucharistic intercessions for the departed:

When the spiritual sacrifice, the unbloody service of God, is performed, we pray to God over this atoning sacrifice for the universal peace of the church, for the welfare of the world, for the emperor, for soldiers and prisoners, for the sick and afflicted, for all the poor and needy. Then we commemorate also those who sleep, the patriarchs, prophets, apostles, martyrs, that God through their prayers and their intercessions may receive our prayer; and in general we pray for all who have gone from us, since we believe that it is of the greatest help to those souls for whom the prayer is offered, while the holy sacrifice, exciting a holy awe, lies before us.

This is clearly an approach to the later idea of purgatory in the Latin church. Even St. Augustine, with Tertullian, teaches plainly, as an old tradition, that the eucharistic sacrifice, the intercessions or suffragia and alms, of the living are of benefit to the departed believers, so that the Lord deals more mercifully with them than their sins deserve.

From: F. L. Cross and E. A. Livingstone, editors, The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, Oxford Univ. Press, 2nd edition, 1983, pp.476, 1221:

It was also widely held from the first that the Eucharist is in some sense a sacrifice, though here again definition was gradual . . . In early post-NT times the constant repudiation of carnal sacrifice and emphasis on life and prayer at Christian worship did not hinder the Eucharist from being described as a sacrifice from the first . . .

From early times the Eucharistic offering was called a sacrifice in virtue of its immediate relation to the sacrifice of Christ.

From: Jaroslav Pelikan, The Emergence of the Catholic Tradition (100-600), Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1971, 146-147:

By the date of the Didache [anywhere from about 60 to 160, depending on the scholar]. . . the application of the term ‘sacrifice’ to the Eucharist seems to have been quite natural, together with the identification of the Christian Eucharist as the ‘pure offering’ commanded in Malachi 1:11 . . .

The Christian liturgies were already using similar language about the offering of the prayers, the gifts, and the lives of the worshipers, and probably also about the offering of the sacrifice of the Mass, so that the sacrificial interpretation of the death of Christ never lacked a liturgical frame of reference . . .

St. Cyril of Jerusalem [c.315-386] in Particular

From: J.N.D. Kelly, Early Christian Doctrines, San Francisco: Harper, revised edition, 1978, 441, 443-444:

Even the pioneer of the conversion doctrine, Cyril of Jerusalem, is careful to indicate that the elements remain bread and wine to sensible perception, and to call them ‘the antitype’ of Christ’s body and blood: ‘the body is given to you in the figure of bread, and the blood is given to you in the figure of wine’. (Cat. 22, 9; 23, 20; 22, 3)

. . . He uses the verb ‘change’ or ‘convert’, pointing out that, since Christ transformed water into wine, which after all is akin to blood, at Cana, there can be no reason to doubt a similar miracle on the more august occasion of the eucharistic banquet. (Cat., 22, 2)

Chrysostom exploits the materialist implications of the conversion theory to the full . . . Thus the elements have undergone a change, and Chrysostom describes them as being refashioned or transformed. In the fifth century conversionist views were taken for granted by Alexandrians and Antiochenes alike. According to Cyril . . . the visible objects are not types or symbols . . . but have been transformed through God’s ineffable power into His body and blood. Elsewhere he remarks that God ‘infuses life-giving power into the oblations and transmutes them into the virtue of His own flesh.’ (Chrysostom: In prod. Iud. hom. I, 6; in Matt. hom. 82, 5; Cyril: In Matt. 26,27; In Luc. 22, 19)

Now I shall cite St. Cyril’s Catechetical Lectures:

7. Moreover, the things which are hung up at idol festivals , either meat or bread, or other such things polluted by the invocation of the unclean spirits, are reckoned in the pomp of the devil. For as the Bread and Wine of the Eucharist before the invocation of the Holy and Adorable Trinity were simple bread and wine, while after the invocation the Bread becomes the Body of Christ, and the Wine the Blood of Christ, so in like manner such meats belonging to the pomp of Satan, though in their own nature simple, become profane by the invocation of the evil spirit. (Lecture 19, 7)

3. Wherefore with full assurance let us partake as of the Body and Blood of Christ: for in the figure of Bread is given to thee His Body, and in the figure of Wine His Blood; that thou by partaking of the Body and Blood of Christ, mayest be made of the same body and the same blood with Him. For thus we come to bear Christ in us, because His Body and Blood are distributed through our members; thus it is that, according to the blessed Peter, we became partakers of the divine nature.

6. Consider therefore the Bread and the Wine not as bare elements, for they are, according to the Lord’s declaration, the Body and Blood of Christ; for even though sense suggests this to thee, yet let faith establish thee. Judge not the matter from the taste, but from faith be fully assured without misgiving, that the Body and Blood of Christ have been vouch-safed to thee.

9. Having learn these things, and been fully assured that the seeming bread is not bread, though sensible to taste, but the Body of Christ; and that the seeming wine is not wine, though the taste will have it so, but the Blood of Christ; . . . (Lecture 22: 3, 6, 9)

7. Then having sanctified ourselves by these spiritual Hymns, we beseech the merciful God to send forth His Holy Spirit upon the gifts lying before Him; that He may make the Bread the Body of Christ, and the Wine the Blood of Christ ; for whatsoever the Holy Ghost has touched, is surely sanctified and changed.

8. Then, after the spiritual sacrifice, the bloodless service, is completed, over that sacrifice of propitiation we entreat God for the common peace of the Churches, for the welfare of the world ; for kings; for soldiers and allies; for the sick; for the afflicted; and, in a word, for all who stand in need of succour we all pray and offer this sacrifice. (Lecture 23: 7-8)

We see, then, that at all points, the beliefs of John Calvin and Kevin Johnson about the Eucharist, as held by the Fathers and St. Cyril of Jerusalem, vis-a-vis Calvin’s view, have been strongly challenged (and I dare say, refuted). If these beliefs are so monstrous as is made out by Calvin, then the Church Fathers en masse are guilty of them just as modern-day Catholics are, and it is absurd to contend that present-day Reformed Protestants (following Calvin) are merely continuing the heritage of the early Church in this regard and others, while Catholics have supposedly departed from it. The exact opposite is true, and I have proven it by citing exclusively Protestant sources and primary patristic sources.