(3-29-04)

***

This is an “outtake” from my 2004 book: The Catholic Verses. It was too historical, and the emphasis of the book is biblical (“the editor hath spoken!”). But this is interesting historical information, I think (at least for a history buff / nut like me), so I saved it for “blog consumption”:

* * * * *

Martin Luther’s eucharistic theology was much closer to Catholic than to Calvinist or Reformed theology (or the purely symbolic conception, which took it a step further). He believed in the Real Presence, although he denied transubstantiation and rejected the Sacrifice of the Mass. Luther (according to his nominalistic, anti-Scholastic leanings) didn’t want to speculate about metaphysics and how the bread and wine became the Body and Blood of Christ. He simply believed in the miracles of the literal presence of Jesus’ Body and Blood “alongside” the bread and wine (consubstantiation). In this respect, his position was similar to the Eastern Orthodox one.

John Calvin didn’t think much of Martin Luther’s opinion in this regard:

. . . if Luther has so great a lust of victory, he will never be able to join along with us in a sincere agreement respecting the pure truth of God. For he has sinned against it not only from vainglory and abusive language, but also from ignorance and the grossest extravagance. For what absurdities he pawned upon us in the beginning, when he said the bread is the very body! And if now he imagines that the body of Christ is enveloped by the bread, I judge that he is chargeable with a very foul error. What can I say of the partisans of that cause? Do they not romance more wildly than Marcion respecting the body of Christ? . . . (Letter to Martin Bucer, January 12, 1538; in Dillenberger, 47)

Note the arrogance and disrespect inherent in this letter, seeing that Calvin was 28 at the time, and writing about Martin Luther, the founder of Protestantism, who was 54. It is not only Catholics who are guilty of slander where Luther is concerned.

Protestant divisions and the perpetual creation of little competing “kingdoms” (along with the usual petty jealousies present in most such situations) existed from the very beginning of the movement, much as they tried to hide this fact from Catholics, knowing that it was scandalous. It will be instructive to briefly examine the “eucharistic controversies,” as they were typical of much of Protestant internal strife throughout history, and illustrate a certain exegetical confusion regarding the Eucharist.

Calvin was very concerned about the public perception of Protestantism. He could be discreet and wise in public pronouncements but he couldn’t hide his true opinions.

In their madness they even drew idolatry after them. For what else is the adorable sacrament of Luther but an idol set up in the temple of God? (Letter to Martin Bucer, June 1549; in Bonnet, V, 234)

In 1544, Luther blasted the “Sacramentarians” (those who denied his doctrine of consubstantiation and opted for a symbolic Eucharist):

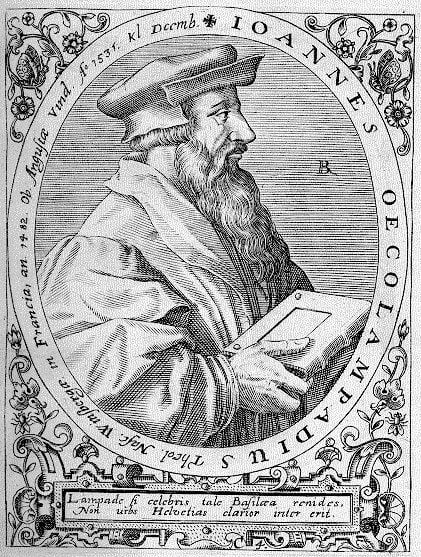

. . . Zwingli, Karlstadt, Oecolampadius . . . called him a baked God, a God made of bread, a God made of wine, a roasted God, etc. They called us cannibals, blood-drinkers, man-eaters . . . even the papists have never taught such things, as they clearly know . . .

For this is . . . how it was accepted in the true, ancient Christian church of fifteen hundred years ago . . . When you receive the bread from the altar, . . . you are receiving the entire body of the Lord; . . . (Brief Confession Concerning the Holy Sacrament, September 1544; Luther’s Works [“LW”], Vol. 38, 291-292)

In this work, Luther calls Zwingli, Karlstadt, Oecolampadius, and Caspar Schwenkfeld (on whose name Luther does a play on words throughout his tract, making it mean “Stinkfield”) -– and by implication those who believe as they do — “fanatics and enemies of the sacrament” (LW, Vol. 38, 287), men who are guilty of “blasphemies and deceitful heresy” (38, 288), “loathsome fanatics” (38, 291), “murderers of souls” (38, 296), who “possess a bedeviled, thoroughly bedeviled, hyper-bedeviled heart and lying tongue” (38, 296), and who “have incurred their penalty and are committing ‘sin which is mortal’,” (38, 296), “blasphemers and enemies of Christ” (38, 302), and “God’s and our condemned enemies” (38, 316).

He described Zwingli as a “full-blown heathen” (38, 290), and wrote: “I am certain that Zwingli, as his last book testifies, died in a great many sins and in blasphemy of God” (38, 302-303). Zwingli had already taken a few swipes at Luther; for example:

May I be lost if he does not surpass Faber in foolishness, Eck in impurity, Cochlaeus in impudence, and to sum it up shortly, all the vicious in vice. (Letter to Conrad Sam of Ulm, August 30, 1528; in Grisar, III, 277)

His successor in Zurich, Heinrich Bullinger, was equally critical:

Everyone must be astonished at the harsh and presumptuous spirit of the man . . . The opinion of posterity will be that Luther was . . . a man ruled by criminal passions.

Luther’s rude hostility might be allowed to pass would he but leave intact respect for Holy Scripture . . . What has already taken place leads us to apprehend that this man will eventually bring great misfortune upon the Church. (Letter to Martin Bucer, December 8, 1543; in Grisar, V, 409 and III, 417)

Philip Melanchthon, Luther’s right hand man and successor, writing to Bullinger on August 30, 1544, described Luther’s Brief Confession (a work on the Eucharist) as “the most atrocious book of Luther ” (atrocissimum Lutheri scriptum, in quo bellum). He had increasingly forsaken his earlier position on the Eucharist and adopted a view closer to Calvin’s, scornfully referring to his former view and that of Luther as “bread worship.”

Ironically, he now adopted a position that he thought should be punished by death earlier in his life (and Lutheran areas had the legal power and Lutheran sanction to carry out the sentence). At length Calvin wrote to Melanchthon:

When I reflect how much, at so unseasonable a time, these intestine quarrels divide and tear us asunder, I almost entirely lose courage . . .

(Letter to Philip Melanchthon, January 21, 1545; in Bonnet, IV, 437)

Calvin wrote his one and only letter to Luther (a conciliatory and respectful one) on the same day, via Melanchthon, but it was never delivered, because – Melanchthon told Calvin – Luther “takes up many things suspiciously” (see Bonnet, IV, 440). Five months later (June 28, 1545), Calvin again wrote to his friend, stating:

I confess that we all owe the greatest thanks to Luther, and I should cheerfully concede to him the highest authority, if he only knew how to control himself. Good God! what jubilee we prepare for the Papists, and what sad example do we set to posterity! (in Schaff, VII, The German Reformation, Chapter 7, §109)

Calvin, despite his friendship with the Lutheran Melanchthon and (sometimes) avowed respect for Luther, wrote 18 years later:

I am carefully on the watch that Lutheranism gain no ground, nor be introduced into France. The best means, believe me, for checking the evil would be that confession written by me . . . (Letter to Heinrich Bullinger, July 2, 1563; in Dillenberger, 76; emphasis added)

Sources

Jules Bonnet, editor, John Calvin: Selected Works of John Calvin: Tracts and Letters: Letters, Part 1, 1528-1545, volume 4 of 7; translated by David Constable; Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Book House, 1983; reproduction of Letters of John Calvin, volume I (Philadelphia: Presbyterian Board of Publication, 1858).

Jules Bonnet, editor, John Calvin: Selected Works of John Calvin: Tracts and Letters: Letters, Part 2, 1545-1553, volume 5 of 7; translated by David Constable; Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Book House, 1983; reproduction of Letters of John Calvin, volume II (Philadelphia: Presbyterian Board of Publication, 1858).

John Dillenberger, editor, John Calvin: Selections From His Writings, Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Co. (Anchor Books), 1971 (Calvin’s letter to Martin Bucer in 1538 was translated by Marcus Robert Gilchrist).

Hartmann Grisar, Luther, translated by E. M. Lamond, edited by Luigi Cappadelta, six volumes, London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., 1915.

Martin Luther, Luther’s Works (LW), American edition, edited by Jaroslav Pelikan (volumes 1-30) and Helmut T. Lehmann (volumes 31-55), St. Louis: Concordia Pub. House (volumes 1-30); Philadelphia: Fortress Press (volumes 31-55), 1955.

Philip Schaff, Philip, History of the Christian Church, New York: Charles Scribner’s sons, 1910, eight volumes; from Volume VII: The German Reformation).

*****

Photo credit: Johannes Oecolampadius (1482-1531). Originally from the book Bibliotheca chalcographica, hoc est Virtute et eruditione clarorum Virorum Imagines. Heidelberg: Clemens Ammon, 1669. [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

***