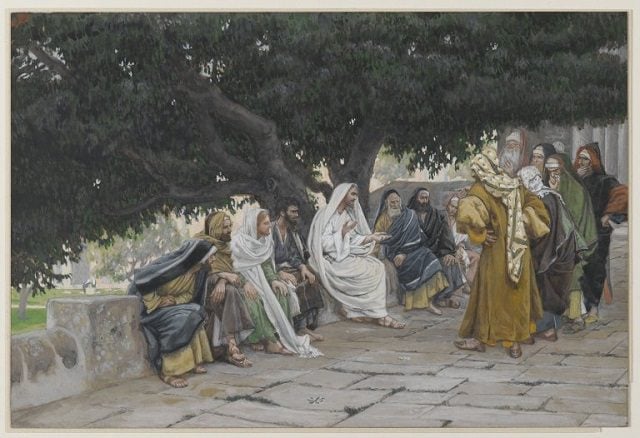

The Pharisees and the Sadducees Come to Tempt Jesus, by James Tissot (1836-1902) [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

***

(12-27-03)

***

The first section of this paper is from my book, The Catholic Verses: 95 Bible Passages That Confound Protestants (Sophia Institute Press, Spring 2004) and is a reply to White’s arguments in his book, The Roman Catholic Controversy (Bethany House, 1996). The second section answers the relevant portion of White’s Internet article, “A Response to David Palm’s Article on Oral Tradition from This Rock Magazine, May, 1995″, and also offers a critique of several erroneous statements and arguments of James White from the book above and another devoted to “biblical authority”: Answers to Catholic Claims (Crowne Publications, 1990). Mr. White’s words will be in blue.

* * * * *

Matthew 23:1-3 (RSV) Then said Jesus to the crowds and to his disciples, 2 “The scribes and the Pharisees sit on Moses’ seat; 3 so practice and observe whatever they tell you, but not what they do; for they preach, but do not practice.”

Reformed Baptist apologist and expert on sola Scriptura, James White, offered a two-page response to the Catholic apologetic use of Matthew 23:1-3 and Moses’ seat. I shall quote the heart of his subtle but thoroughly fallacious argument:

Some Roman Catholics present this passage as proof that a source of extrabiblical authority received the blessing of the Lord Jesus. It has been alleged that the concept of “Moses’ seat” is in fact a refutation of sola scriptura, for not only is this concept not found in the Old Testament, but Jesus seemingly gives His approbation to this extrascriptural tradition . . .The “Moses’ seat” refers to a seat in the front of the synagogue on which the teacher of the Law sat while reading from the Scriptures. Synagogue worship, of course, came into being long after Moses’ day, so those who attempt to make this an oral tradition going back to Moses are engaging in wishful thinking.

(The Roman Catholic Controversy, Minneapolis: Bethany House Publishers, 1996, 100)

White agrees that the notion is not found in the Old Testament but maintains that it cannot be traced back to Moses. That probably is correct, yet the Catholic argument here does not rest on whether it literally can be traced historically to Moses, but on the fact that it is not found in the Old Testament. Thus, White – from the outset – concedes a fundamental point of the Catholic argument concerning authority and sola Scriptura.

White then cites Bible scholar Robert Gundry in agreement, to the effect that Jesus was binding Christians to the Pharisaical law, but not “their interpretative traditions.” This passage concerned only “the law itself” with the “antinomians” in mind. How Gundry arrives at such a conclusion remains to be seen. White’s query about the Catholic interpretation, “is this sound exegesis?” can just as easily be applied to Gundry’s fine-tuned distinctions which help him avoid any implication of a binding extrabiblical tradition. White continues:

There was nothing in the tradition of having someone read from the Scriptures while sitting on Moses’ seat that was in conflict with the Scriptures . . . It is quite proper to listen and obey the words of the one who reads from the Law or the Prophets, for one is not hearing a man speaking in such a situation, but is listening to the very words of God. (Ibid., 101)

This is true as far as it goes, but it is essentially a non sequitur and amounts to eisegesis of the passage (which is ironic, because now White plays the role of “a man speaking” and distorting “the very words of God”). Jesus said:

“The scribes and the Pharisees sit on Moses’ seat; so practice and observe whatever they tell you, but not what they do; for they preach, but do not practice.”

First, it should be noted that nowhere in the actual text is the notion that the Pharisees are only reading the Old Testament Scripture when sitting on Moses’ seat. It’s an assumption gratuitously smuggled in from a presupposed position of sola Scriptura.

Secondly, White’s assumption that Jesus is referring literally to Pharisees sitting on a seat in the synagogue and reading (the Old Testament only) – and that alone – is more forced and woodenly literalistic than the far more plausible interpretation that this was simply a term denoting received authority.

It reminds one of the old silly Protestant tale that the popes speak infallibly and ex cathedra (cathedra is the Greek word for seat in Matthew 23:2) only when sitting in a certain chair in the Vatican (because the phrase means literally, “from the bishop’s chair”; whereas it was a figurative and idiomatic usage).

Jesus says that they sat “on Moses’ seat; so practice and observe whatever they tell you.” In other words: because they had the authority (based on the position of occupying Moses’ seat), therefore they were to be obeyed. It is like referring to a “chairman” of a company or committee. He occupies the “chair,” therefore he has authority. No one thinks he has the authority only when he sits in a certain chair reading the corporation charter or the Constitution or some other official document.

Yet this is how White would exclusively interpret Jesus’ words. The Eerdmans Bible Dictionary, in its article, “Seat”, allows White’s reading as a secondary interpretation, but seems to regard the primary meaning of this term in the manner I have described:

References to seating in the Bible are almost all to such as a representation of honor and authority . . .According to Jesus, the scribes and Pharisees occupy “Moses’ seat” (Matt. 23:2), having the authority and ability to interpret the law of Moses correctly; here “seat” is both a metaphor for judicial authority and also a reference to a literal stone seat in the front of many synagogues that would be occupied by an authoritative teacher of the law.

(Allen C. Myers, editor, The Eerdmans Bible Dictionary, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans, 1987; English revision of Bijbelse Encyclopedie, edited by W. H. Gispen, Kampen, Netherlands: J. H. Kok, revised edition, 1975; translated by Raymond C. Togtman and Ralph W. Vunderink; 919-920)

The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia (article, “Seat”) takes the same position, commenting specifically on our verse:

It is used also of the exalted position occupied by men of marked rank or influence, either in good or evil (Mt 23:2; Ps 1:1).(James Orr, editor, The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., five volumes, 1956; IV, 2710)

White makes no mention of these considerations, but it is difficult to believe that he is not aware of them (since he is a Bible scholar well-acquainted with the nuances of biblical meanings). They don’t fit in very well with the case he is trying to make, so he omits them. But the reader is thereby left with an incomplete picture.

Thirdly, because they had the authority and no indication is given that Jesus thought they had it only when simply reading Scripture, it would follow that Christians were, therefore, bound to elements of Pharisaical teaching that were not only non-scriptural, but based on oral tradition, for this is what Pharisees believed. They fully accepted the binding authority of oral tradition (the Sadducees were the ones who were the Jewish sola scripturists and liberals of the time). The New Bible Dictionary describes their beliefs in this respect, in its article, “Pharisees”:

. . . the Torah was not merely ‘law’ but also ‘instruction’, i.e., it consisted not merely of fixed commandments but was adaptable to changing conditions . . . This adaptation or inference was the task of those who had made a special study of the Torah, and a majority decision was binding on all . . .The commandments were further applied by analogy to situations not directly covered by the Torah. All these developments together with thirty-one customs of ‘immemorial usage’ formed the ‘oral law’ . . . the full development of which is later than the New Testament. Being convinced that they had the right interpretation of the Torah, they claimed that these ‘traditions of the elders’ (Mk 7:3) came from Moses on Sinai.

(J. D. Douglas, editor, The New Bible Dictionary, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans Pub. Co., 1962; 981-982)

Likewise, The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church notes in its article on the Pharisees:

Unlike the Sadducees, who tried to apply Mosaic Law precisely as it was given, the Pharisees allowed some interpretation of it to make it more applicable to different situations, and they regarded these oral interpretations as of the same level of importance as the Law itself.(F. L. Cross and E. A. Livingstone, editors, The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, 1983; 1077)

Fourthly, it was precisely the extrabiblical (especially apocalyptic) elements of Pharisaical Judaism that New Testament Christianity adopted and developed for its own: doctrines such as: resurrection, the soul, the afterlife, eternal reward or damnation, and angelology and demonology (all of which the Sadducees rejected). The Old Testament had relatively little to say about these things, and what it did assert was in a primitive, kernel form. But the postbiblical literature of the Jews (led by the mainstream Pharisaical tradition) had plenty to say about them. Therefore, this was another instance of Christianity utilizing non-biblical literature and traditions in its own doctrinal development.

Fifth, Paul shows the high priest, Ananias, respect, even when the latter had him struck on the mouth, and was not dealing with matters strictly of the Old Testament and the Law, but with the question of whether Paul was teaching wrongly and should be stopped (Acts 23:1-5). A few verses later Paul states, “I am a Pharisee, a son of Pharisees” (23:6) and it is noted that the Pharisees and Sadducees in the assembly were divided and that the Sadducees “say that there is no resurrection, nor angel, nor spirit; but the Pharisees acknowledge them all” (23:7-8). Some Pharisees defended Paul (23:9).

Next, White mentions (presumably as a parallel to the Pharisees and Moses’ seat) Nehemiah 8: a passage I dealt with previously:

Indeed, when Ezra read the Law to the people in Nehemiah, chapter 8, the people listened attentively and cried “Amen! Amen!” at the hearing of God’s Word. (White, ibid., 101)

He conveniently neglects to mention, however, that Ezra’s Levite assistants, as recorded in the next two verses after the evangelical-sounding “Amens,” “helped the people to understand the law” (8:7) and “gave the sense, so that the people understood the reading” (8:8).

So this supposedly analogous example (that is, if presented in its entirety; not selectively for polemical purposes) does not support Dr. White’s and Dr. Gundry’s position that the authority of the Pharisees applied only insofar as they sat and read the Old Testament to the people (functioning as a sort of ancient collective Alexander Scourby, reading the Bible onto a casssette tape for mass consumption), not when they also interpreted (which was part and parcel of the Pharisaical outlook and approach).

One doesn’t find in the Old Testament individual Hebrews questioning teaching authority. Sola Scriptura simply is not there. No matter how hard White and other Protestants try to read it into the Old Testament, it cannot be done. Nor can it be read into the New Testament, once all the facts are in. White, however, writes:

And who can forget the result of Josiah’s discovery of the Book of the Covenant in 2 Chronicles 34? (Ibid., 101)

Indeed, this was a momentous occasion (White probably thinks it is similar in substance and import to the myth and legend of Martin Luther supposedly “rescuing” or “initiating” the Bible in the vernacular, when in fact there had been fourteen German editions of the Bible in the 70 years preceding his own).

But if the implication is that the Law was self-evident simply upon being read, per sola Scriptura, this is untrue to the Old Testament, for, again, we are informed in the same book that priests and Levites “taught in Judah, having the book of the law of the LORD with them; they went about through all the cities of Judah and taught among the people” (2 Chron 17:9), and that the Levites “taught all Israel” (2 Chron 35:3). They didn’t just read, they taught, and that involved interpretation. And the people had no right of private judgment, to dissent from what was taught.

White and all Protestants believe that any individual Christian has the right and duty to rebuke their pastors if what they are teaching is “unbiblical” (that is, according to the lone individual). This is an elegant, quaint theory indeed, on paper, but it doesn’t quite work the same way in practice. I know this from my own experience as a former Protestant, for when I rebuked my Assemblies of God pastor in a private letter (because he had preached from the pulpit, “keep your pastors honest”), I was publicly renounced and rebuked from the pulpit (in a most paranoid, alarmist manner) as a theologically-inexperienced rabble-rouser trying to cause division.

White’s arguments in his Internet treatment of this passage fare scarcely any better under close scrutiny than his weak and fallacious reasoning in his book, and further demonstrate the persistently inconsistent and incoherent nature of his apologetics (when he is opposing Catholicism).

. . . the term itself is not common in Jewish writings. It most likely refers to a seat in the synagogue from which the law (i.e., the writings of Moses and the prophets) was read. Obviously, since synagogue worship did not exist prior to the Exile, the term “ancient Israel” here needs to be limited to the intertestamental period.

(“A Response to David Palm’s Article on Oral Tradition from This Rock Magazine, May, 1995″)

Secondly, the authority of “Moses’ seat” would have been primarily magisterial, not doctrinal. Lightfoot notes this by saying, “This is to be understood rather of the legislative seat (or chair), than of the merely doctrinal: and Christ here asserts the authority of the magistrate, and persuadeth to obey him in lawful things” (Commentary on the New Testament from the Talmud and Hebraica, II, 289). Moses acted as judge in Israel, and the priesthood maintained that role in the theocracy.

White does not give us the reasoning that Lightfoot uses to come to this conclusion. I don’t see anything in the text itself that limits it to legislative or judicial functions. Lightfoot, it should be noted, however, does not take an absolute position that no doctrine is involved, as shown by his phrase “merely doctrinal.” Thus, White can only argue the weaker position that their function was “primarily magisterial.”

This concession is the proverbial “hole in the dam,” because if they possess any doctrinal authority at all, by the sanction of our Lord Jesus Himself, then sola Scriptura is in dire straits indeed, for that would be a position quite analogous (though not perfectly so) to that of the Catholic Church: the authoritative interpreter of Christian doctrine and Guardian of Apostolic Tradition. Furthermore, Moses certainly gave and authoritatively interpreted doctrine, as did the priesthood in Israel (see, e.g., Nehemiah 8:7-8, above). It is a bit strange to argue that those occupying a position described as “Moses’ seat” would not have this teaching authority.

Mr. Palm notes that we do not find this office in the Old Testament. This is true, as far as the specific name goes.

So much for Jesus only citing the Old Testament as authoritative . . . Dr. White may not have this opinion, but many Protestant do.

It is then asserted that Jesus’ refusal to overthrow the form of synagogue worship and teaching is tantamount to a recognition of extra-biblical binding revelation. The close observer will note a huge chasm here.

I don’t think it is necessary to offer this argument in such strong terms. Binding interpretation of a revelation is not the same as a new revelation. What the passage clearly demonstrates, I think, is that there is authoritative tradition outside of the Bible, and even outside of the apostles, who were alive at the time this encounter took place, and soon to appear on the scene with great zeal, after Jesus’ Resurrection. Jesus could easily have said that the Pharisees’ authority was to shortly be superseded by the apostles but He did not, and even Paul called himself a Pharisee and recognized the authority of the high priest.

The religious situation into which the Messiah came was hardly identical with the situation under Moses.

This is a non sequitur. The force of this particular argument does not rest upon whether “Moses’ Seat” literally goes back to Moses. Rather, the salient point is whether it was a binding authority not based on solely the letter of the Old Testament. If so, sola Scriptura is in deep trouble.

Many things were different, and due to occupation, Roman rule, and many other factors, there were all sorts of things that were “extra-biblical” that were part and parcel of the Jewish life of the day. Are we to honestly believe that unless the Lord Jesus proved a revolutionary in rejecting every non-biblical tradition and practice that this gives us wholesale license for the addition of such traditions today?

Yes, but they are not “additions”; they were there from the beginning (in the Catholic view), and merely developed. The fact remains that Jesus accepted this particular “non-biblical tradition and practice”. James White knows it, so he is playing the game of trying to minimize and de-emphasize this acceptance. It’s a futile effort, and in so doing, he is already conceding four-fifths of the case (and trying to make out that he has not). Besides, Jesus was certainly a “radical” and a nonconformist through and through. Does White really think that He would have refrained from dissenting against any state of affairs or set of beliefs that He did not agree with?

I see little reason to believe that He would do so, from the record we have. But White would have us believe that our Lord Jesus let a few of these “non-biblical tradition[s] and practice[s]” slip through the cracks, so to speak (even with regard to a class of people whom He vigorously condemns for hypocrisy on several occasions). This makes no sense at all, and it is special pleading.

Or should we not realize that in light of Jesus words in Matthew 15 that such traditions need to be tested by a higher authority (Scripture), and, if they do not violate the Word of God, they can be followed and practiced?

St. Paul said far worse of the Galatians than Jesus said of the Pharisees in Matthew 15 and elsewhere, yet he continued to regard them as brothers in Christ and as a “church” (for this example and many other similar ones, see my paper: “Sins and Sinners in the Catholic Church”). Why is it so unthinkable for Jesus to do the same with the Pharisees? In John 11:49-52, the Apostle John tells us that Caiaphas, the high priest “prophesied” and spoke truth (an act which can only be inspired by the Holy Spirit). Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimathea were righteous Pharisees. Jesus was even buried in the latter’s tomb.

As for the traditions needing to be harmonious with Scripture; of course, no one denies that. But the question at hand is whether there can be a legitimate tradition not found (i.e., not described or written about) in Scripture itself. Something can be absent in Scripture but nevertheless in perfect harmony with it.

There was nothing against the Scriptures in having a man read the Scriptures from Moses’ seat, or to give judgments based upon the Law. Why then reject such a tradition?

White assumes what he is trying to prove: Jesus had to be upholding sola Scriptura; therefore, the Pharisees possession of the office of “Moses’ Seat” means only that they sat and read the Scripture from this seat in the synagogue. This is preposterous and can only be asserted (with the hope that people will accept it without questioning its nonexistent basis). The priests and the later rabbis interpreted the Law and the Scripture. The Pharisees also believed in an oral tradition received by Moses on Mt. Sinai when he received the Ten Commandments and the Law. Pharisees were the “mainstream Jewish tradition” at that time. The Sadducees were the “liberals” who rejected the resurrection and other things that all Christians believe. And they were the ones who accepted sola Scriptura, since they rejected the oral tradition.

The acceptance of a tradition that is not contrary to Scripture is not grounds for the acceptance of others that are.

Catholics wholeheartedly agree; this is why we reject sola Scriptura and other Protestant novel doctrines which are not found in Holy Scripture.

And what is more, the acceptance of a tradition current at the time does not mean that the Lord Jesus accepted the claims made by the Mishnah two hundred years later regarding the alleged basis of such traditions (i.e., those claims regarding Mosaic origin).

Regarding the Mishnaic tractate Aboth, it does indeed make the claim that Mr. Palm notes. However, are we to gather from Mr. Palm’s citation that he believes this claim? It is hard to believe that he actually does – in fact, unless Mr. Palm has undergone a recent conversion to Judaism, I can’t possibly see how he could do so. Let’s note a few things:

1) The tractate indicates that the Torah was passed down to such individuals as Shammai and Hillel, yet, as students of NT backgrounds know, these two set up opposing schools with different understandings of tradition (should sound familiar!). Who was, in fact, the true recipient of this alleged oral tradition, then?

I find this an extremely interesting argument, given the multiplicity of Protestant schools of thought, which endlessly conflict and contradict (thus making the existence of much falsehood and error in Protestant ranks logically certain and inevitable). White contends that because there were two schools of interpretation in later Judaism, therefore, the very notion of oral tradition itself is somehow suspect and must be discarded. Why, then, is he not similarly troubled and perplexed about the state of affairs in Protestantism? He firmly believes that there is one Christian truth, and that it is so clear in Scripture, but Protestants are unable to find it. And if one group has found it, how does the man on the street determine which group has done so?

Does this sad state of affairs make him skeptical of the inspired revelation of Scripture? Of course not. He believes it despite the multitude of competing interpretations and schools of thought. So why is it so inconceivable that there could also be such a thing as a true tradition, even though all do not hold it or acknowledge it? This is one of the many double standards inherent in White’s contra-Catholic polemics. He doesn’t apply the same standard to his own Protestant beliefs that he applies to Catholics.

In 1996, when I was a member of James White’s “sola Scriptura Internet list,” he and I had a discussion about what I described as the “perspicuous apostolic message,” which had to do with this aspect of the Bible message and Christian truth being so “clear,” yet Protestants not being able to agree on it. He argued that this isn’t a problem at all, because it is easily explained by the fact that “men are sinners,” etc. I dealt with this desperate evasion in my paper: Perspicuity (Clarity) of Holy Scripture. So in his book, The Roman Catholic Controversy, White states on page 91:

The Bible is absolutely clear in the sense that the Westminster Confession states:

“Those things which are necessary to be known, believed and observed for salvation, are so clearly propounded and opened in some place of Scripture or other, that not only the learned, but the unlearned, in a due use of the ordinary means, may attain to a sufficient understanding of them.”

Does it follow, then, that there must be a unanimity of opinion on infant baptism? Does the above statement of the Confession even say that there will be a unanimity of opinion on the items that “are necessary to be known, believed and observed for salvation”? No, it does not. And why not? Because people – sinful people, people with agendas, people who want to find something in the Bible that isn’t really there – approach Scripture, and no matter how perfect it is, people are fallible.

One could have a field day with all the fallacies and errors in this facile analysis. I’ve noted many times in my apologetics that the “sin argument” concerning Protestant diversity of opinion is absurdly simplistic and remarkably judgmental, and casts doubt on major Protestant figures who couldn’t agree. Luther disagreed with Calvin on whether baptism regenerates and on the Real Presence in the Eucharist, so who was right? Well, for White, Calvin was, because he agrees with him over against Luther.

But why did Luther get these “obvious” biblical teachings wrong? Well, again, according to White’s suspicious and cynical mindset, that is because he must have been a “sinful” person with an “agenda” that fatally clouded his approach to Scripture, and made him see things in it which weren’t “really there.” Trouble is, White has to also dissent from Calvin and side with the Anabaptists concerning adult baptism, so Calvin’s sin kept him from seeing that clear truth of Scripture, and so on and so forth.

The whole thing reduces to absurdity and belittles great figures in Protestant history in a way that even Catholics do not have to do. We can simply regard each of these men as holding some false beliefs in all sincerity, and different interpretive traditions and ways of approaching Scripture and the Christian life. We believe they were mistaken in many things, of course, but we don’t have to run them down as unable to see the “clear” truths of Scripture due to some blindness in their character or thinking. Only the sort of Protestant view that White holds entails that sort of judgmentalism.

Secondly, regarding the Westminster Confession and its statement, “Those things which are necessary to be known, believed and observed for salvation, are so clearly propounded,” for many Christians, including Luther and Lutherans, traditional Anglicans, and Methodists, and even later Protestant schools of thought such as the Churches of Christ, one of the things which is necessary for salvation is baptism. Therefore, it would be clearly taught in Scripture (per theWestminster Confession). And so all these groups, and Catholics and Orthodox, believe it indeed is clearly taught in the Bible. But Protestants cannot agree on the correct teaching, and are split into five major camps. There is a reason why most Christians throughout history have accepted baptismal regeneration. It is clearly taught in Scripture!:

Acts 2:38 And Peter said to them, “Repent, and be baptized every one of you in the name of Jesus Christ for the forgiveness of your sins; and you shall receive the gift of the Holy Spirit.” (RSV)

Acts 22:16 And now why do you wait? Rise and be baptized, and wash away your sins, calling on his name.

Titus 3:5 he saved us, not because of deeds done by us in righteousness, but in virtue of his own mercy, by the washing of regeneration and renewal in the Holy Spirit,

1 Peter 3:19-21 in which he went and preached to the spirits in prison, 20 who formerly did not obey, when God’s patience waited in the days of Noah, during the building of the ark, in which a few, that is, eight persons, were saved through water. 21 Baptism, which corresponds to this, now saves you, not as a removal of dirt from the body but as an appeal to God for a clear conscience, through the resurrection of Jesus Christ,

(see also, Bible on Salvation via Baptism & Eucharist; John 3:5 & Titus 3:5: Baptismal Regeneration?; Baptismal Regeneration: More Biblical Evidence)

According to James White, the people who see baptismal regeneration in these passages, are “sinful people, people with agendas, people who want to find something in the Bible that isn’t really there.” And presumably many of those Protestants who reject adult baptism or non-regenerative baptism think the same of White, since they accept the same principle of perspicuity of Scripture that he accepts. They must explain somehow why Protestants can’t agree on such an important doctrine, given this “clearness” of Scripture. So they accuse others of blinding sinfulness, or they claim that baptism is merely a “secondary issue,” upon which men can disagree, and that’s fine and dandy, or else they start to question perspicuity itself. On page 92 of the same book, White writes:

Are we to believe that the Bible is so unclear and self-contradictory that we cannot arrive at the truth through an honest, whole-hearted effort at examining its evidence? It seems that is what Rome is telling us. But because the Scriptures can be misused, it does not follow that they are insufficient to lead us to the truth . . . The reason that Rome tells us the Bible is insufficient, I believe, is so we will be convinced of Rome’s ultimate authority and abandon the God-given standard of Scripture.

I don’t have to believe this as a Catholic. I think Scripture is pretty clear (I’ve always found it to be so in my many biblical studies), but I also know from simple observation and knowledge of Church history that it isn’t clear enough to bring men to agreement. White says that is because of sin and stupidity. Certainly those things are always potential factors. But I say the rampant disagreement is primarily because of a false rule of faith: sola Scriptura, which excludes the binding authority of tradition and the Church, which entities produce the doctrinal unity that sola Scriptura has never, and can never produce. So “Rome” doesn’t “tell us” what White thinks it tells us. What Catholics teach is that central authority and tradition is necessary for doctrinal unity; whether Scripture is “clear” or unclear. And we think Scripture itself teaches this (which is precisely why we believe it).

White thinks in dichotomous terms (a characteristic and widespread Protestant shortcoming), so for him, to accept binding Church authority is to somehow”abandon the God-given standard of Scripture,” as if it were a zero-sum game where Scripture is the air in a glass and the Church is the water added to the glass: the more water (“Church”) is added, the less Scripture there can be, so that a full glass of “the Church” leaves no room for the Bible at all as the “standard.” Of course, none of this is Catholic teaching, nor does it logically follow from the notion of Church authority. It’s a false dilemma and false dichotomy. But a certain Protestant mindset and mentality cannot grasp this. Thus, White states in another book:

One will either subjugate tradition to Scripture (as the Reformers taught) or one will subjugate Scripture to tradition, and this is what we see in Roman Catholicism. The Pharisees, too, denied that they were in any way denigrating the authority of Scripture by their adherence to the “traditions of their fathers.” But Jesus did not accept their claim. He knew better. He pointed out how their traditions destroyed the very purpose of God’s law, allowing them to circumvent the clear teaching of the Word through the agency of their traditions . . . If Christ was right to condemn the Pharisees for their false traditions, then the traditions of Rome, too, must be condemned.

(Answers to Catholic Claims: A Discussion of Biblical Authority, Southbridge, Massachusetts: Crowne Publications, Inc., 1990, 56)

What about the many false traditions in Protestantism? We know for a fact that many many such false traditions exist because there are competing views which contradict each other. That entails (as a matter of logical necessity) that someone is wrong, and dead-wrong. They can’t all be right. There can’t be five true doctrines of baptism simultaneously. Therefore, false “traditions of men” exist in Protestantism, and would be condemned by Jesus just as vigorously as supposed “false traditions” of Catholicism.

But do we ever hear White railing against those? Of course not. He doesn’t write books and articles about Martin Luther’s grave errors (from his own point of view) or about those of, say. St. Augustine (even though neither would qualify as a Christian if we adopt White’s criteria for same, as I demonstrated beyond all doubt, I think, in my paper: “‘Man-Centered’ Sacramentalism: The Remarkable Incoherence of James White’) Instead, he accepts the view (or at least his behavior suggests this) that a lot of Christian doctrine is up for grabs and is “secondary.” He winks at the diversity, just as all Protestants must, faced with an opponent like the Catholic Church, which has at least preserved doctrinal unity (whether one agrees with the content of that unified doctrine or not).

And that gets us back to my experience with White on his sola Scriptura list. White argued that Protestants accepted what the apostles taught, and that this was why they rejected the alleged corrupt innovations and unbiblical additions of “Rome.” I asked him what was it, precisely, that the apostles taught, so that I could know where I was in error, operating from the perfectly self-evident background assumption that, in order to have fidelity” to an “apostolic message,” one must know what it is and define it. This would constitute some sort of criteria for “orthodoxy” in Protestant ranks.

White hemmed and hawed and never offered an answer to this very simple question, based on his own claims. To my mind, this proved that he had no basisfor his claim in the first place; no content to speak of. It just sounded nice, and duly impressive. This is the classic characteristic of sophistry. He said justification by faith was one of these (which was fine, except for the extreme difficulty of finding Church Fathers who differed from the Catholic position), and the deity of Christ (which was beside the point, since all Nicene Christians accept that). Then he challenged me, asking whether the Bible was too unclear to resolve 18 questions concerning which I asked him to tell me what the apostles believed (18 areas where I knew Protestants could not come to agreement). I replied that it was irrelevant what I thought; I was asking him what in fact the apostles taught, since he was making the claim that Protestants were only following the “perspicuous apostolic authority.”

Pressed, White admitted that Protestants disagreed on all 18 of the points I raised, but “so what?” I then asked White if he could tell me what the apostles taught on just five of the 18 issues, and what he meant by “apostolic message.” He refused to answer and tried to change the subject to Catholic authority. Then he said that I was aware that my question had been answered (!!). And so on and on we went, round and round. White never answered my simple question, and opted for various evasions, topic-changes, and obfuscation and obscurantism. He knew full well that whatever answer he gave would make many other Protestants non-apostolic and essentially “out of the fold.” He knew what I was driving at, which is why, I believe, that he refused to answer. But in any event, the answer from his own stated perspective should have been very easy to give. It was a case study in avoiding proclamations that one can’t back up under the least bit of scrutiny and examination.

. . . Next Mr. Palm says that since the Pharisees stood in this alleged line of succession, their teaching deserved to be respected. The problem is, however, that the Lord Jesus often did not respect their teaching. The issue in Matthew 23 was not respect for the teaching of the Pharisees, but respect for the authority of the person who sat in Moses’ seat. The two are not necessarily co-extensive, . . .

It’s very difficult to argue that Jesus did not refer to their teaching, seeing that He said, “practice and observe whatever they tell you.” One has to believe that this “whatever” included no doctrine. To make such an arbitrary distinction between “authority” and “teaching” is ludicrous (especially the more one knows about Jewish teaching methods and the history of Hebrew religion). If Jesus had said, rather: “practice and observe whatever I tell you,” or, “practice and observe whatever the apostles tell you,” White wouldn’t have the slightest doubt about what was meant. He wouldn’t play around, eisegete the text, and try to limit the scope and extent of the authority.

and what is more, there is nothing in the passage that even begins to suggest that the Lord Jesus is making reference to the entire idea of extra-biblical tradition, authority, etc.

No? This is plainly false, by the following straightforward logic:

1. Jesus said of the Pharisees, “practice and observe whatever they tell you.”

2. But Pharisees believed in an authoritative oral tradition, which included some content not included in the Bible (but not necessarily contrary to biblical teaching).

3. Therefore, Jesus was giving sanction to the teaching authority of oral “extra-biblical” tradition.

He is saying to obey the authorities in the synagogue service.

No He isn’t; he is saying, “practice and observe whatever they tell you.” That is not limited to the synagogue, much as White might wish it to be so, for his own purposes.

To read into this the acceptance of an entire concept of oral revelation passed down through some “magisterium” is to be way beyond what is written.

It doesn’t have to be “oral revelation”; only authoritative oral teaching that goes beyond the letter of Scripture. That is enough to be blatantly contrary to sola Scriptura.

Mr. Palm then says, “Jesus here draws on oral Tradition to uphold the legitimacy of this teaching office in Israel.” This is simply untrue. There is nothing in the passage that even makes reference to “oral Tradition.”

“Moses’ Seat” was such a tradition, which was not in the Bible. The very term comes from oral tradition. The words “oral tradition” don’t have to be there; the content is. This is a remarkably silly statement from a man as educated as White. Even he agrees that the notion of “Moses’ Seat” is not found in the Old Testament, and that it comes from Jewish tradition.

This can only be identified as wishful thinking, based upon an anachronistic insertion of later developments back into the text.

If you have no case, grotesquely exaggerate the flaws in the opponent’s position (or manufacture some) and hope that your readers (or jurors, as the case may be) will be fooled . . .

. . . Mr. Palm’s attempt to use the chair of Moses suffers from the same problem as his first attempt: it assumes what it seeks to prove. It is circular, and does not provide anywhere near sufficient basis for its conclusions.

That is far more true of White’s reply, as I think has been abundantly shown by now. Elsewhere in the article, White wrote:

It must be remembered that Jewish writers (including Matthew) felt much freer to engage in conflation and paraphrastic citation than we in our modern Western world . . . And why should we believe that Mr. Palm’s leap into the undocumentable realm of “oral tradition” is any more solid than any of the suggestions that have been given for a Scriptural source?

If anything could be drawn at all from the phrase h’rethen dia twn prophetwn, it would be that this is indeed a conflated citation, drawn from the plurality of the prophets rather than from a single prophet.

This shows that White’s preconceived notion is that whatever is cited in some authoritative manner in the New Testament will somehow be shown to be from the Old Testament, even if this entails citing several passages together as one. Thus he writes in one of his books:

Did Jesus give place to the Jewish leaders’ claim that they were the true inheritors of the traditions of Moses? Did He for a second acquiesce to their claim of “interpretive authority”? Surely not. He held those who claimed to “sit in the seat of Moses” accountable to the words of Scripture, despite their claim to be in sole possession of the “correct interpretation.” . . . Jesus did not participate in their “veneration” of “tradition.”

. . . just as He rebuked the elders of the people of Israel for making the word of God null and void through their supposedly authoritative traditions, He would say the same thing today to the Roman Catholic people . . . For Him, the Word was final, it was not lacking in anything.

(Answers . . ., 30-32)

But that assumption is strictly arbitrary, of course. White admits that the New Testamwnt writers drew from many sources (he could hardly deny this even if he wanted to), but of course he has to deny that any were authoritative. With Matthew 23:1-3 it is different because Jesus is sanctioning Pharisaical authority in a blanket sense. In so doing, He necessarily is giving legitimacy to oral tradition, for this is what the Pharisees believed.

What is more, Mr. Palm slips into the common misrepresentation of sola scriptura that fills Roman Catholic apologetics works: the idea that sola scriptura, if it is true, must be normative during times of revelation.

Why would it not be? On what basis? The Bible says no more about this concept (exactly nothing) than it does about sola Scriptura itself. A false, novel principle is introduced with no biblical substantiation, then it is made the formal rule of faith of Protestantism, then it is argued that things were different during Bible times than they were now, with regard to the demands and nature of sola Scriptura. I just don’t see any indication of that in Scripture.

If White does claim such scriptural support exists, he should, by all means, produce this biblical evidence. We all wait with baited breath. If he cannot do so, why does he believe this? He would have to do so on “extra-biblical” grounds, and to do that is to concede virtually his entire position, as any number of distinctive Catholic doctrines could be defended as also not explicitly biblical. But I maintain that there is no biblical proofs whatsoever for what White is contending (sola Scriptura and the idea that it only really starts applying after the Bible is complete). It’s completely arbitrary, and yet another instance of begging the question and assuming what one is purporting to prove.

Sola scriptura refers to the functioning church, not to the church being founded and receiving revelation on a regular basis from living apostles.

I ask again, where is the support for this idea in Scripture itself?

There are no living apostles today, and revelation has ceased (even Rome agrees on this point). The issue now is, what is the infallible rule of faith? Does the Bible teach that that which is theopneustos (“God-breathed”) is sufficient to function as the regula fidei? Yes, it does. That is the issue.

But where??!! The Bible is sufficient for salvation and teaching, but it does not follow from those truths, that the Church and Tradition are not binding and authoritative. Sola Scriptura is not so much false in what it asserts but in what it fails to assert, and what it positively excludes, contrary to Scripture.

In his book, Answers to Catholic Claims: A Discussion of Biblical Authority, White goes to even further extremes by coming to his conclusions for little reason other than his preconceived notions (more circular argumentation). Thus, he argues:

But what of 2 Timothy 2:2? Does this not indicate the existence of an oral teaching that could be passed down separately from the written record? . . .

. . . are we to believe that what Paul taught in the presence of many witnesses is different than what is contained in the pages of the New Testament? . . . Why should we limit what Timothy is to pass on to only those things that are not contained in the Bible, but instead make up some “traditions” that were to be entrusted to a particular class of individuals – those holding the “apostolic succession”? There is nothing to suggest that there was the slightest difference between what Paul had taught publicly and what he had written . . . Are we also to assume that there is more in the “oral teaching” than we have in the New Testament? Why? On what basis?

(Answers, 59-60)

In this case, White has answered his own question in his later book, The Roman Catholic Controversy:

1. First and foremost, sola scriptura is not a claim that the Bible contains all knowledge . . . Those who point out that there are truths outside the Bible are not objecting to sola scriptura.

2. Sola scriptura is not a claim that the Bible is an exhaustive catalog of all religious knowledge. When John commented on the wide range of the Lord Jesus’ ministry, he wrote:

And there are also many other things which Jesus did, which if they were written in detail, I suppose that even the world itself would not contain the books that would be written (John 21:25)

(pages 56-57)

Sola scriptura does not entail the rejection of every kind or form of “tradition.” There are some traditions that are God-honoring and useful in the Church. Sola scriptura simply means that any tradition, no matter how ancient or venerable it might seem to us, must be tested by a higher authority, and that authority is the Bible.

(page 59)

White asks (above): “Why should we limit what Timothy is to pass on to only those things that are not contained in the Bible?” Indeed, why should we? Since the Catholic Church certainly doesn’t do this, I wonder why the question was asked? It is a non sequitur. Apparently unaware that these two strains of thought are contradictory, White repeatedly engages in massive question-begging in his earlier book:

But what of Acts 2:42? Does it not say that the early Church, long before the writing of any of the New Testament, was devoted to the apostles’ teaching? Yes, it does say that. But again, what does this have to do with the concept of the Bible being the sufficient rule of faith? We are not living in the time of the apostles, are we? New revelation is not being given right now, is it? . . . Then Acts speaks to us of a very unusual time, does it not? There is nothing in the fact that the early believers in Jerusalem devoted themselves to the Apostles’ teaching that indicates that this teaching to which they devoted themselves is other than what we have in the New Testament! Is there anything that would suggest that what the Apostles taught these early believers was different than what they taught believers later by epistle? Do we not have accounts of the early sermons in the book of Acts that tell us what the Apostles were teaching then? Do we find the Apostles saying “what we tell you now we will pass down only by mouth as a separate mode of revelation known as tradition, and later we will write down some other stuff that will become sacred Scripture”? Certainly not. The fact that the early believers were devoted to the Apostles’ teaching should only strengthen our desire to also be devoted to the Apostles’ teaching – as it is found in the sacred Scriptures.

(Answers, 40-41)

There is absolutely no indication whatsoever that there is any difference in content between the message preached to the Thessalonians and the one contained in the written epistle. The Roman Catholic Church has no basis in this passage [2 Thessalonians 2:15] at all to assert that the contents of these “traditions” differs [sic] in the slightest from what is contained in the New Testament.

Are we to assume that when Paul proclaimed the Gospel that he said something different than when he wrote his epistles? No, both Peter and Paul mean the same thing when they speak of evangelizing.

(Ibid., 61)

. . . for many Roman Catholic apologists, simply demonstrating that the apostles spoke something is enough to demonstrate that the written word is not sufficient. The underlying assumption is that what was spoken has to contain information that is not in what was written. . . We point out that there is no basis for asserting that the spoken teachings of the apostles differed in any way from the written record they left to us. There is no evidence of a belief in a second “mode” of revelation in the New Testament – no acknowledgment of a revelation outside of that given by the Spirit in the Scriptures.

(Ibid., 62)

White again engages in rhetorical irrelevancy by asking, “Do we find the Apostles saying “what we tell you now we will pass down only by mouth as a separate mode of revelation known as tradition, . . . ?” What this has to do with anything, I have not the slightest idea. But I guess it helps White to bolster his extremely weak case – with holes large enough for a truck to drive through -, to pretend that Catholics believe in sola traditio. Perhaps he can explain this exceedingly strange line of thinking in his reply (in the rare event that he does respond).

The transitional period to which White refers (“We are not living in the time of the apostles, are we? New revelation is not being given right now, is it?”, etc.), would actually be far longer than the lifetime of the apostles. It would extend all the way to the end of the 4th century, when the canon of the Bible was fixed (including the so-called “Apocrypha,” which was included in Bibles all the way till the advent of Protestantism, when these books were “demoted” and first removed). So sola Scriptura could not be applied in the sense it is today, until almost 400 A.D., when Church authority and Tradition set the limits of the canon. Does this not strike one as an exceptionally odd and weird point of view? The question of the canon itself is an extremely fascinating one and troublesome for sola Scriptura, but that is beyond our purview here.

One must also call attention to the fact that being separate from Scripture does not automatically mean “different from the teaching of Scripture.” There need not be any conflict. Catholics believe that Scripture and Tradition are “twin fonts of the one divine wellspring.” Sacred Tradition is not so much “different” from Scripture as it is “more.” So White sets up a false dilemma. Arguing from the reasonable proposition that it is implausible that oral tradition would be “different” from Scripture, he falsely concludes that, therefore, no oral tradition exists, or if it does, it is irrelevant, and not binding in any way, shape, or form. He overlooks the possibility that oral tradition can supplement the Bible and offer authoritative interpretation of it (because he sees the two as somehow pitted against each other – which itself is a false and unbiblical dichotomy).

But White does more than even this. He practically equates the “tradition” often spoken of in the New Testament with the New Testament itself:

. . . A person with a Bible in his hands has the traditions of which Paul speaks. (Ibid., 58)

This is clearly absurd, and it is from plain common sense. James White admits that the Bible does not contain all knowledge, or even all religious knowledge, and cited John 21:25 to show this. There are many other such verses (e.g., Lk 24:15-16,25-27, Jn 20:30, Acts 1:2-3). Jesus appeared for forty days after His Resurrection, in addition to all the days and nights He spent with the disciples teaching them. In one night He very well could have spoken more words than are in the entire New Testament. And He was with them for three years. St. Paul spent many years with Christians, and is described frequently as “arguing” or “disputing” with Gentiles and Jews. It is ludicrous and ridiculous to think that either Jesus or Paul were “Scripture machines” and that absolutely everything they taught (i.e., the ideas and doctrines) was later recorded in Scripture, and had to be, lest it be forgotten, and that nothing they taught was not in Scripture.

Consider, for example, just one passage: the account of Jesus’ post-Resurrection appearance to the two disciples on the road to Emmaus (Lk 24:13-32). They talked for probably several hours, and the Bible informs us of one wonderfully tantalizing Scripture interpretation session from our Lord Himself (that every Bible student would give his right arm to have heard):

And beginning with Moses and all the prophets, he interpreted to them in all the scriptures the things concerning himself. (Luke 24:27)

It is absurd to think that nothing in any of these gatherings was spoken which was not later recorded in Scripture: no idea, no doctrine or explanation of a doctrine or interpretation of various Scriptures (that the disciples and early Christians would have surely asked Jesus and Paul about). It is equally absurd to hold that no one could remember any of this, and that it could not become a Christian Tradition supplementary to and alongside Holy Scripture, and in perfect harmony with it. This would require a notion that all of this teaching was quickly forgotten and lost to posterity, and that only the Bible contained the truths which Christians need. Nothing else carried a similar authority. This scenario is implausible in the extreme; even laughably so. Yet White’s empty axiom requires it.

On what basis does White assert these things? How does he know this? What proves it? When all is said and done, it will be seen that his assumption is based on nothing at all. It is an unproven axiom that he adopts simply because it fits into the schema of sola Scriptura. He assumes it without argument, and this premise is used in an overall sola Scriptura framework, but it is, of course, yet another circular argument: a vicious logical circle indeed. The “reasoning” (insofar as I can comprehend such incoherence) runs as follows:

1. When Paul refers to tradition he is referring to nothing more than what is in the Bible.

2. Therefore, there is no tradition to speak of, since it simply collapses or reduces as a category to “that which is in Scripture.”

3. Therefore, the Catholic rule of faith (which includes so-called “unbiblical tradition”) is unbiblical.

4. Whatever is unbiblical must be false.

5. Whatever is false must be rejected.

6. Therefore, the Protestant rule of faith, sola Scriptura, is true over against the Catholic “three-legged stool” of authority: tradition + Church + Bible.

The whole chain starts with a radically unproven premise. It proceeds to add error upon error and to build a house of cards, on sand. All indications from the Bible and from common sense; all plausiblity, suggests that #1 is false to begin with. But White thinks it is so true that he repeats it several times (often italicizing entire sentences), hoping that people who read it over and over will accept it and not notice that no evidence or biblical rationale whatsoever has been given, which would cause a reasonable person who accepts biblical inspiration to believe this.

We conclude, then, that White’s arguments regarding sola Scriptura are filled with fallacies and insufficiently-supported contentions, begged questions and circular arguments. They collapse in a heap under even mild scrutiny, like a snowman on the equator. He ignores biblical evidence which contradicts his outlook, and to the extent that he engages such passages at all, he caricatures the Catholic position and simply redefines words away so that – presto! – the problem vanishes. If one sees the word “tradition” in the Bible, one must realize that it is merely a synonym for “Bible.” When Jesus upholds the authority of the Pharisees, it means only that they can read the Bible in the synagogue, and cannot mean anything contrary to the preconceived axiom of sola Scriptura. When the New Testament writers cite “prophecies” that can’t be found in the Old Testament, we will find them one day, and no one must rashly conclude that they are “extra-biblical.” Etc., etc.

The old proverb never was more apt of a description than it is with regard to the sola Scriptura position, as defended even by its most vigorous proponents: “you can’t make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear.”