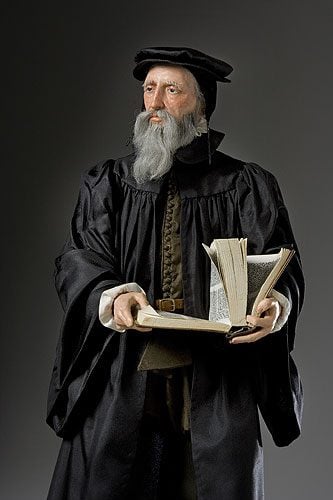

Historical mixed media figure of John Calvin produced by artist/historian George S. Stuart and photographed by Peter d’Aprix: from the George S. Stuart Gallery of Historical Figures archive [Wikimedia Commons / Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license]

***

This is an installment of a series of replies (see the Introduction and Master List) to much of Book IV (Of the Holy Catholic Church) of Institutes of the Christian Religion, by early Protestant leader John Calvin (1509-1564). I utilize the public domain translation of Henry Beveridge, dated 1845, from the 1559 edition in Latin; available online. Calvin’s words will be in blue. All biblical citations (in my portions) will be from RSV unless otherwise noted.

Related reading from yours truly:

Biblical Catholic Answers for John Calvin (2010 book: 388 pages)

A Biblical Critique of Calvinism (2012 book: 178 pages)

Biblical Catholic Salvation: “Faith Working Through Love” (2010 book: 187 pages; includes biblical critiques of all five points of “TULIP”)

*****

(4-28-09)

***

IV, 1:3-5

*

3. What meant by the Communion of Saints. Whether it is inconsistent with various gifts in the saints, or with civil order. Uses of this article concerning the Church and the Communion of Saints. Must the Church be visible in order to our maintaining unity with her?

Moreover, this article of the Creed relates in some measure to the external Church, that every one of us must maintain brotherly concord with all the children of God, give due authority to the Church, and, in short, conduct ourselves as sheep of the flock.

Bravo! A sorely needed exhortation for Protestants today . . .

And hence the additional expression, the “communion of saints;” for this clause, though usually omitted by ancient writers, must not be overlooked, as it admirably expresses the quality of the Church; just as if it had been said, that saints are united in the fellowship of Christ on this condition, that all the blessings which God bestows upon them are mutually communicated to each other. This, however, is not incompatible with a diversity of graces, for we know that the gifts of the Spirit are variously distributed; nor is it incompatible with civil order, by which each is permitted privately to possess his own means, it being necessary for the preservation of peace among men that distinct rights of property should exist among them.

More admirable emphases . . . When Calvin is right, he is really right, and when he is wrong, he is dead-wrong.

Still a community is asserted, such as Luke describes when he says, “The multitude of them that believed were of one heart and of one soul” (Acts 4:32); and Paul, when he reminds the Ephesians, “There is one body, and one Spirit, even as ye are called in one hope of your calling” (Eph. 4:4). For if they are truly persuaded that God is the common Father of them all, and Christ their common head, they cannot but be united together in brotherly love, and mutually impart their blessings to each other.

Amen! Yet Calvin’s theology and ecclesiology ultimately war against and undermine this strong desire for profound unity, and the sad thing is that he never seems to have seen the irony or to have recognized the causal relationship between his teaching (where it departs from Catholic, apostolic tradition) and the fruits of the so-called “Reformation.” Luther was the same way. I suppose it was too painful to acknowledge that their false teachings led to so much social uproar and doctrinal and ecclesiological chaos. Luther hints at times at this (and in the Peasants’ Revolt, the connection — at least partially — is undeniably obvious), but never directly acknowledges it.

Then it is of the highest importance for us to know what benefit thence redounds to us. For when we believe the Church, it is in order that we may be firmly persuaded that we are its members.

Again, Calvin’s denial (per all the Protestant revolutionaries) of conciliar and ecclesial infallibility directly undermines his recommending Christians to “believe the Church.” For anyone always has a “loophole” to say (because of the Protestant bedrock principles of sola Scriptura and private judgment and supremacy of the individual conscience over against received tradition), “except in the case of doctrine A, where Mother Church is obviously wrong . . . ” And as we know from constant experience with loopholes and “hard cases”, the loophole soon becomes a gaping hole big enough for a truck to drive through, and the “hard case” and “exception to the rule” soon becomes the norm. Therefore, to assert a strong Church authority without the essential component of binding authority and infallibility, is self-defeating: if not immediately in principle, then inevitably in practice. This is plainly one fatal flaw in Calvin’s ecclesiology.

In this way our salvation rests on a foundation so firm and sure, that though the whole fabric of the world were to give way, it could not be destroyed. First, it stands with the election of God, and cannot change or fail, any more than his eternal providence. Next, it is in a manner united with the stability of Christ, who will no more allow his faithful followers to be dissevered from him, than he would allow his own members to be torn to pieces.

That’s right: whoever is truly of God’s elect will be saved and cannot not be saved. That is a truism. But, as Calvin himself knows (noted in my last installment), no one person can be positive that they are included in the elect. Thus, it is an abstract (and definitely true) concept we can discuss, but it has no bearing on our alleged absolute assurance of salvation. Yet to this day many thousands of Calvinists (often now observed on the Internet) are perfectly obsessed with these notions of predestination and the elect, and frantically determining who is “in” and who is “out” (often with the utmost lack of charity and also blatant anti-Catholic prejudice and ignorance). Christians surely have far better and more important things to do to spend their time on. But this is one way that Satan zaps the energy and effectiveness of Christians: to keep them preoccupied with abstracts that have little or no bearing on day-to-day life and discipleship. We all tend to fall into this and have to be vigilant to avoid it. The harvest is plentiful and the laborers are few.

We may add, that so long as we continue in the bosom of the Church, we are sure that the truth will remain with us.

“Sure”? This is untrue, given Protestant principles, that always allow the individual the right to judge and reject various teachings of the Church, just as Luther did, and as Calvin did, following his model of dissent. Just as they dissented against the Catholic Church, so (by the same epistemological and ecclesiological principles and premises) Protestants can dissent against their mere denominations and their supposed high “authority”. Hence, denominations (even though utterly despised and condemned by both Luther and Calvin) were inevitable. How ironic and sad . . . Former Lutheran and Catholic convert Louis Bouyer, in his classic book, The Spirit and Forms of Protestantism, makes an extended, fascinating (and, I think, compelling) argument about how Protestantism’s first principles inevitably led to results not at all desired by the so-called “reformers” themselves.

There is a reason all of that occurred in history (it wasn’t just a random accident): why the splits and divisions never end. It’s because they are latent in the first principles of the Protestant movement. The Protestants were warned by the Church what would occur if they insisted on these premises (we Catholics knew full well what schism would lead to, and always leads to), but they refused to heed the advice. They knew better. The Church is wise enough to take the “long view” of history, and cause and effect. This is part and parcel of her Spirit-led wisdom. But the first Protestants, for some strange reason that has always been inexplicable to me, didn’t seem to be able to see beyond their own noses, or have the slightest inkling of what their novel premises and fundamentals would lead to. Their ongoing strength was basically only as good as their amount of agreement with ancient Catholic teachings (a notion also argued by Louis Bouyer in his book, cited above).

Lastly, we feel that we have an interest in such promises as these, “In Mount Zion and in Jerusalem shall be deliverance” (Joel 2:32; Obad. 17); “God is in the midst of her, she shall not be moved” (Ps. 46:5). So available is communion with the Church to keep us in the fellowship of God. In the very term communion there is great consolation; because, while we are assured that everything which God bestows on his members belongs to us, all the blessings conferred upon them confirm our hope. But in order to embrace the unity of the Church in this manner, it is not necessary, as I have observed, to see it with our eyes, or feel it with our hands. Nay, rather from its being placed in faith, we are reminded that our thoughts are to dwell upon it, as much when it escapes our perception as when it openly appears.

All of this outwardly great thought about the Church, yet it is contradicted by Calvin’s rule of faith, which (as history has now amply shown) in fact undermined all of this marvelously touted assurance and certainty and supposed guarantee of institutional (as well as doctrinal) unity. It’s a case study of internal incoherence leading to bad consequences. Ideas do have consequences, after all.

Nor is our faith the worse for apprehending what is unknown, since we are not enjoined here to distinguish between the elect and the reprobate (this belongs not to us, but to God only), but to feel firmly assured in our minds, that all those who, by the mercy of God the Father, through the efficacy of the Holy Spirit, have become partakers with Christ, are set apart as the proper and peculiar possession of God, and that as we are of the number, we are also partakers of this great grace.

Another worthy statement of caution, urging his followers to not speculate about who is of the elect and who is not: tragically unheeded by many Calvinists and also “instantaneous salvation / eternal security” sorts of Protestants: the result being much worthless and unedifying conversation and fruitless speculation. If they would all simply heed Calvin’s advice, this could be avoided and maybe the seemingly endless energy and zeal could be expended towards a bit more important activities, such as, for example, reaching out to the lost and sharing the gospel with them, rather than foolishly concluding that fellow Christians (notably, Catholics) are certainly lost and should be condemned and treated with extreme harshness for being supposedly lost and “enemies of God,” etc. May the Lord help us all to be good stewards of our time.

4. The name of Mother given to the Church shows how necessary it is to know her. No salvation out of the Church.

But as it is now our purpose to discourse of the visible Church,

Note that Calvin maintains a notion of the visible Church: not merely invisible. We saw this also in his reference to the “external Church” in the previous section. Thus, he accepts this “Catholic” belief; he is simply inconsistent in applying it and in blending it with his rule of faith, where an inherent incoherence and a clash of principles is entailed.

let us learn, from her single title of Mother, how useful, nay, how necessary the knowledge of her is, since there is no other means of entering into life unless she conceive us in the womb and give us birth, unless she nourish us at her breasts, and, in short, keep us under her charge and government, until, divested of mortal flesh, we become like the angels (Mt. 22:30).

An extraordinary expression of Church authority . . . Calvin essentially states that the Church is necessary for salvation (virtually asserting, “outside the Church there is no salvation”), which is, of course, Catholic doctrine, and foreign to the mentality of many Protestants today, and even from the beginning of their movement, for those (such as the Anabaptists) termed “radical reformers” even by fellow Protestants.

For our weakness does not permit us to leave the school until we have spent our whole lives as scholars. Moreover, beyond the pale of the Church no forgiveness of sins, no salvation, can be hoped for, as Isaiah and Joel testify (Isa. 37:32; Joel 2:32).

Calvin asserts the same thing in even stronger terms, and it’s certainly true as far as Calvin intends it. . . this should be required, standard reading for every Protestant and regularly taught in their Sunday schools. And then we Catholics need to tell them after they learn this basic stuff, that an infallible Church is the necessary and perfectly natural accompaniment of this true teaching of the necessity of the Church as Mother and trustworthy teacher. Protestants don’t have that (don’t even claim to have it); we both claim it and actually possess it, by God’s express design, and only due to His supernatural guidance and protection. Here are Calvin’s prooftexts, that are interesting insofar as they are specifically tied to the OT concept of “remnant”:

Isaiah 37:31-32 And the surviving remnant of the house of Judah shall again take root downward, and bear fruit upward; [32] for out of Jerusalem shall go forth a remnant, and out of Mount Zion a band of survivors. The zeal of the LORD of hosts will accomplish this.

Joel 2:32 And it shall come to pass that all who call upon the name of the LORD shall be delivered; for in Mount Zion and in Jerusalem there shall be those who escape, as the LORD has said, and among the survivors shall be those whom the LORD calls.

To their testimony Ezekiel subscribes, when he declares, “They shall not be in the assembly of my people, neither shall they be written in the writing of the house of Israel” (Ezek. 3:9); as, on the other hand, those who turn to the cultivation of true piety are said to inscribe their names among the citizens of Jerusalem. For which reason it is said in the psalm, “Remember me, O Lord, with the favour that thou bearest unto thy people: O visit me with thy salvation; that I may see the good of thy chosen, that I may rejoice in the gladness of thy nation, that I may glory with thine inheritance” (Ps. 106:4, 5). By these words the paternal favour of God and the special evidence of spiritual life are confined to his peculiar people, and hence the abandonment of the Church is always fatal.

In other words, Calvin draws a useful and compelling analogy between the chosen nation of Israel in the Old Covenant, and the Body of Christ, the Church, in the New Covenant. He often makes good analogical arguments of this sort. I have utilized one of them myself in my own apologetics: his analogy (following Paul) between circumcision and infant baptism.

5. The Church is our mother, inasmuch as God has committed to her the kind office of bringing us up in the faith until we attain full age. This method of education not to be despised. Useful to us in two ways. This utility destroyed by those who despise the pastors and teachers of the Church. The petulance of such despisers repressed by reason and Scripture. For this education of the Church her children enjoined to meet in the sanctuary. The abuse of churches both before and since the advent of Christ. Their proper use.

But let us proceed to a full exposition of this view. Paul says that our Saviour “ascended far above all heavens, that he might fill all things. And he gave some, apostles; and some, prophets; and some, evangelists; and some, pastors and teachers; for the perfecting of the saints, for the work of the ministry, for the edifying of the body of Christ: till we all come in the unity of the faith, and of the knowledge of the Son of God, unto a perfect man, unto the measure of the stature of the fulness of Christ” (Eph. 4:10-13). We see that God, who might perfect his people in a moment, chooses not to bring them to manhood in any other way than by the education of the Church.

Amen! So much for the radical versions of sola Scriptura rampant today: what are often sarcastically called by the more articulate Protestants, solo Scriptura. Calvin’s version, though still ultimately internally incoherent, at least still had a strong place for the Church (even if partially erroneously defined). We should give credit where it is due.

We see the mode of doing it expressed; the preaching of celestial doctrine is committed to pastors. We see that all without exception are brought into the same order, that they may with meek and docile spirit allow themselves to be governed by teachers appointed for this purpose.

One can hardly be “governed” by pastors if one always has the “right” to question their authority at every turn by a bogus appeal to “private judgment.” I have firsthand experience of this internal contradiction myself. My old pastor used to say from the pulpit: “keep your pastors honest and correct them from the Bible if they go astray.” Well, I did that, and it wasn’t pretty. I was denounced from the pulpit as a troublemaker. So Protestants can question their pastors in good conscience but at the same time they can’t. The same tension is present in Calvin and never satisfactorily resolved. He himself took very poorly to being corrected by anyone, and was brutal with theological opponents (even, at times, with Luther himself). Yet he had no authority than anyone else. He simply assumed it without adequate reason. Calvin once described Lutheranism as “evil.” Lutherans and Calvinists bitterly fought and wrangled in wars with words, too. Who was right? More importantly for our purposes, how could the two settle their differences, since both appealed to Scripture and claimed to be authoritative? As we know, there was no way to resolve the conundrum.

Isaiah had long before given this as the characteristic of the kingdom of Christ, “My Spirit that is upon thee, and my words which I have put in thy mouth, shall not depart out of thy mouth, nor out of the mouth of thy seed, nor out of the mouth of thy seed’s seed, saith the Lord, from henceforth and for ever” (Isa. 59:21).

A good description of the very infallibility of the Church that Calvin rejects . . .

Hence it follows, that all who reject the spiritual food of the soul divinely offered to them by the hands of the Church, deserve to perish of hunger and famine.

And how do we find this Church so we may follow its heaven-sent teaching? We look for Calvin and wherever he is, is where the one true Church resides?

God inspires us with faith, but it is by the instrumentality of his gospel, as Paul reminds us, “Faith cometh by hearing” (Rom. 10:17). God reserves to himself the power of maintaining it, but it is by the preaching of the gospel, as Paul also declares, that he brings it forth and unfolds it.

Indeed. There is a perfectly motivating reason for evangelism, and lots of it. We are vehicles used by God to distribute His grace.

With this view, it pleased him in ancient times that sacred meetings should be held in the sanctuary, that consent in faith might be nourished by doctrine proceeding from the lips of the priest.

How often do we hear this sort of language from Calvinists today? They need to go back to their roots, from within their own paradigm, just as Catholics need to do that, too.

Those magnificent titles, as when the temple is called God’s rest, his sanctuary, his habitation, and when he is said to dwell between the cherubims (Ps 32:13, 14; 80:1), are used for no other purpose than to procure respect, love, reverence, and dignity to the ministry of heavenly doctrine, to which otherwise the appearance of an insignificant human being might be in no slight degree derogatory. Therefore, to teach us that the treasure offered to us in earthen vessels is of inestimable value (2 Cor. 4:7), God himself appears and, as the author of this ordinance, requires his presence to be recognised in his own institution.

Indeed; this is the same sort of sentiment that causes we Catholics to believe in the Real Presence in the Eucharist. Calvin obviously didn’t see that connection, having rejected the apostolic, patristic, Catholic doctrine of the substantial presence and substituted a mystical, “spiritual” presence which is scarcely indistinguishable from the omnipresence of God.

Accordingly, after forbidding his people to give heed to familiar spirits, wizards, and other superstitions (Lev. 19:30, 31), he adds, that he will give what ought to be sufficient for all—namely, that he will never leave them without prophets.

Luther seemed to think he was some sort of prophet. Maybe Calvin did, too (and if so, was, of course — very unlike Luther, — too humble to ever assert his office), which would explain a lot.

For, as he did not commit his ancient people to angels, but raised up teachers on the earth to perform a truly angelical office, so he is pleased to instruct us in the present day by human means.

Yes; but we disagree that these “human means” can ever contradict the received doctrines of the Church.

But as anciently he did not confine himself to the law merely, but added priests as interpreters, from whose lips the people might inquire after his true meaning,

Authoritative interpretation! How interesting . . .

so in the present day he would not only have us to be attentive to reading, but has appointed masters to give us their assistance. In this there is a twofold advantage. For, on the one hand, he by an admirable test proves our obedience when we listen to his ministers just as we would to himself;

Obedience to the Church is a good thing, but again, what is the true Church; why should we think Calvin heads it (rather than, say, Luther or Henry VIII or various Anabaptist “prophets”), etc.?

while, on the other hand, he consults our weakness in being pleased to address us after the manner of men by means of interpreters, that he may thus allure us to himself, instead of driving us away by his thunder.

Exactly. God always uses men because we respond better to our own.

How well this familiar mode of teaching is suited to us all the godly are aware, from the dread with which the divine majesty justly inspires them. Those who think that the authority of the doctrine is impaired by the insignificance of the men who are called to teach, betray their ingratitude; for among the many noble endowments with which God has adorned the human race, one of the most remarkable is, that he deigns to consecrate the mouths and tongues of men to his service, making his own voice to be heard in them.

This is an excellent argument for the lack of impeccability in the pope not being any sort of reason to suppose that God is not speaking through him. The pope is “consecrated” in those special instances where he proclaims a doctrine to be infallible. God is “making his own voice to be heard in them”. I don’t think any Catholic could have expressed it more eloquently.

Wherefore, let us not on our part decline obediently to embrace the doctrine of salvation, delivered by his command and mouth; because, although the power of God is not confined to external means, he has, however, confined us to his ordinary method of teaching, which method, when fanatics refuse to observe, they entangle themselves in many fatal snares.

Indeed. The ones who disagreed with Calvin, were, relatively, “fanatics.” But how is that essentially different from the Catholic Church’s stance whereby it deemed that Protestantism was a radical dissenting movement? Calvin (rather remarkably) everywhere seems to assume that the Church now resides peculiarly in his own environs. Yet he can’t prove that the ancient Catholic Church has decisively fallen away from its unique status. He assumes it, just as Luther does. In other places, however, he will acknowledge some remote remnant of the true Church remaining in Catholicism (such as his position that it retains true baptism and some other genuine attributes; see, e.g., Inst., IV, 2:11-12), but apart from that, he thinks the “ball has been passed” to the Calvinist “Church” as the remnant, over against the Catholic Church headed by the pope.

Pride, or fastidiousness, or emulation, induces many to persuade themselves that they can profit sufficiently by reading and meditating in private, and thus to despise public meetings, and deem preaching superfluous. But since as much as in them lies they loose or burst the sacred bond of unity, none of them escapes the just punishment of this impious divorce, but become fascinated with pestiferous errors, and the foulest delusions.

A wonderful condemnation of sectarianism and the “lone ranger” Christian, that we see so often today.

Wherefore, in order that the pure simplicity of the faith may flourish among us, let us not decline to use this exercise of piety, which God by his institution of it has shown to be necessary, and which he so highly recommends. None, even among the most petulant of men, would venture to say, that we are to shut our ears against God, but in all ages prophets and pious teachers have had a difficult contest to maintain with the ungodly, whose perverseness cannot submit to the yoke of being taught by the lips and ministry of men.

Indeed. That’s why Catholics have always been concerned to maintain the teaching ministry of the magisterium: popes, bishops, councils, priests, catechisms. Calvin systematically got rid of all except some sort of catechism: an odd thing to do if he was concerned with the high importance of a guiding teaching authority.

This is just the same as if they were to destroy the impress of God as exhibited to us in doctrine. For no other reason were believers anciently enjoined to seek the face of God in the sanctuary (Ps. 105:4) (an injunction so often repeated in the Law), than because the doctrine of the Law, and the exhortations of the prophets, were to them a living image of God. Thus Paul declares, that in his preaching the glory of God shone in the face of Jesus Christ (2 Cor. 4:6). The more detestable are the apostates who delight in producing schisms in churches, just as if they wished to drive the sheep from the fold, and throw them into the jaws of wolves.

Exactly. Once we determine what schism is and what the true Church is, then it is seen that Calvin participated in and fostered the very thing that he vociferously condemned over and over. That is the ironic tragedy of his revolutionary movement.

Let us hold, agreeably to the passage we quoted from Paul, that the Church can only be edified by external preaching, and that there is no other bond by which the saints can be kept together than by uniting with one consent to observe the order which God has appointed in his Church for learning and making progress. For this end, especially, as I have observed, believers were anciently enjoined under the Law to flock together to the sanctuary; for when Moses speaks of the habitation of God, he at the same time calls it the place of the name of God, the place where he will record his name (Exod. 20:24); thus plainly teaching that no use could be made of it without the doctrine of godliness. And there can be no doubt that, for the same reason, David complains with great bitterness of soul, that by the tyrannical cruelty of his enemies he was prevented from entering the tabernacle (Ps. 84).

Yet many of Calvin’s very followers were iconoclasts and had quite a low view of sanctuaries, since they went around smashing statues even of Christ, and organs, and stained glass, as if they were some evil thing. The same sanctuary Calvin refers to (the old temple and tabernacles) had huge images of cherubim on the walls. But the profoundly biblical notions of sacred and holy places and of physical objects as aids of worship have gradually become nonexistent among Protestants (particularly Calvinists).

To many the complaint seems childish, as if no great loss were sustained, not much pleasure lost, by exclusion from the temple, provided other amusements were enjoyed. David, however, laments this one deprivation, as filling him with anxiety and sadness, tormenting, and almost destroying him. This he does because there is nothing on which believers set a higher value than on this aid, by which God gradually raises his people to heaven. For it is to be observed, that he always exhibited himself to the holy patriarchs in the mirror of his doctrine in such a way as to make their knowledge spiritual. Whence the temple is not only styled his face, but also, for the purpose of removing all superstition, is termed his footstool (Ps. 132:7; 99:5). Herein is the unity of the faith happily realised, when all, from the highest to the lowest, aspire to the head. All the temples which the Gentiles built to God with a different intention were a mere profanation of his worship,—a profanation into which the Jews also fell, though not with equal grossness. With this Stephen upbraids them in the words of Isaiah when he says, “Howbeit the Most High dwelleth not in temples made with hands; as saith the Prophet, Heaven is my throne,” &c. (Acts 7:48). For God only consecrates temples to their legitimate use by his word. And when we rashly attempt anything without his order, immediately setting out from a bad principle, we introduce adventitious fictions, by which evil is propagated without measure.

All true . . .

It was inconsiderate in Xerxes when, by the advice of the magians, he burnt or pulled down all the temples of Greece, because he thought it absurd that God, to whom all things ought to be free and open, should be enclosed by walls and roofs, as if it were not in the power of God in a manner to descend to us, that he may be near to us, and yet neither change his place nor affect us by earthly means, but rather, by a kind of vehicles, raise us aloft to his own heavenly glory, which, with its immensity, fills all things, and in height is above the heavens.

Another good argument for the “holy place” . . . Would that Calvinists today felt the same way. A Christian church set aside for worship of God is not a barn or a gymnasium or a sports arena or airplane hangar. It is a holy and sanctified place, set aside. Calvin commendably argues all this, yet it is clearly a consciousness that is largely lost among Calvinists and other Protestants today. In this respect, Calvin sounds far more Catholic than Protestant (though not in agreement with us in all respects, even in this area).