This is one of my many critiques of the book entitled, Roman but Not Catholic: What Remains at Stake 500 Years after the Reformation, by evangelical Protestant theologian Kenneth J. Collins and Anglican philosopher Jerry L. Walls (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Academic, 2017).

*****

Kenneth Collins, in his chapter 2: “Tradition and the Traditions” — after railing against supposedly untethered, unchecked, unbiblical Catholic traditions — states about purgatory in particular:

To rectify this considerable deficit in terms of both earlier church history and generous scriptural support, a deficit that was at times embarrassing, medieval theologians such as Rabanus Maurus (on the doctrine of purgatory) simply appealed to the tradition itself or, by implication, to the Holy Spirit as the guarantee of the tradition . . . simply all-too-human teaching. How do we know that such is merely human teaching? It is at variance with the clear teaching of sacred Scripture.

There is considerable irony and humor here, once one discovers that Jerry Walls, Collins’ co-author of this book, wrote a book defending purgatory. Therefore, he has defended something (at book-length) that Collins thinks is “all-too-human” and “at variance with the clear teaching of sacred Scripture.” It’s “clear” to Collins that Scripture teaches no such thing as purgatory. It’s clear to Walls (and folks like, e.g., C. S. Lewis) that it does teach it. How do Protestants resolve such internal contradictions? They can’t; and it’s one of their major problems. They will never solve it, either. They haven’t in 500 years, so there is no reason to think that they will or can at this late juncture.

Collins thinks that the history of the doctrine is so scarce and nonexistent as to be “embarrassing” and a “considerable deficit.” Yet Walls in his book managed to find enough of such history that Timothy George, dean of Beeson Divinity School of Samford University, wrote a review (on the Amazon page), in which he states: “Walls traces Christian views on purgatory from the early church to C. S. Lewis and comes up with a surprisingly affirmative conclusion . . .” Someone’s gotta be wrong here. The doctrine is either present in the Church fathers or it is not.

As an editor of three books of Church fathers quotations, I am personally acquainted with plenty of such documentation. Cardinal Newman observed that there was much more in the fathers about purgatory, than there is regarding original sin (which almost all Protestants accept). Here is some of that historical data (I could easily provide much more than this):

In short, inasmuch as we understand “the prison” pointed out in the Gospel to be Hades, and as we also interpret “the uttermost farthing” to mean the very smallest offence which has to be recompensed there before the resurrection, no one will hesitate to believe that the soul undergoes in Hades some compensatory discipline, without prejudice to the full process of the resurrection, when the recompense will be administered through the flesh besides. (Tertullian, A Treatise on the Soul, chapter 58; ANF, Vol. III)

But we say that the fire sanctifies not flesh, but sinful souls; meaning not the all-devouring vulgar fire but that of wisdom, which pervades the soul passing through the fire. (St. Clement of Alexandria, Stromata / Miscellanies, Book VII, Chapter 6; ANF, Vol. II)

It is one thing to stand for pardon, another thing to attain to glory: it is one thing, when cast into prison, not to go out thence until one has paid the uttermost farthing; another thing at once to receive the wages of faith and courage. It is one thing, tortured by long suffering for sins, to be cleansed and long purged by fire; another to have purged all sins by suffering. It is one thing, in fine, to be in suspense till the sentence of God at the day of judgment; another to be at once crowned by the Lord. (St. Cyprian, Epistle 51 [55], To Antonianus, 20; ANF, Vol. V, 332)

[A]fter his departure out of the body, he gains knowledge of the difference between virtue and vice, and finds that he is not able to partake of divinity until he has been purged of the filthy cobntagion in his soul by the purifying fire. (St. Gregory of Nyssa, Sermon on the Dead)

[St. Ambrose] clearly stated that the prayers of the living could help to relieve the suffering of the dead, that suffrages could be of use in mitigating the penalties meted out in the other world. (Jacques Le Goff, The Birth of Purgatory, University of Chicago Press, 1984, 60)

If the man whose work is burnt and is to suffer the loss of his labour, while he himself is saved, yet not without proof of fire: it follows that if a man’s work remains which he has built upon the foundation, he will be saved without probation by fire, and consequently a difference is established between one degree of salvation and another (St. Jerome, Against Jovinianus, Book II, 22; NPNF 2, Vol. VI)

From these words it more evidently appears that some shall in the last judgment suffer some kind of purgatorial punishments; for what else can be understood by the word, “Who shall abide the day of His entrance, or who shall be able to look upon Him? For He enters as a moulder’s fire, and as the herb of fullers: and He shall sit fusing and purifying as if over gold and silver: and He shall purify the sons of Levi, and pour them out like gold and silver?” [Mal 3:2-3] Similarly Isaiah says, “The Lord shall wash the filthiness of the sons and daughters of Zion, and shall cleanse away the blood from their midst, by the spirit of judgment and by the spirit of burning.” [Isaiah 4:4] . . . when he says, “And he shall purify the sons of Levi, and pour them out like gold and silver, and they shall offer to the Lord sacrifices in righteousness; and the sacrifices of Judah and Jerusalem shall be pleasing to the Lord,” [Mal 3:3-4] he declares that those who shall be purified shall then please the Lord with sacrifices of righteousness, and consequently they themselves shall be purified from their own unrighteousness which made them displeasing to God. Now they themselves, when they have been purified, shall be sacrifices of complete and perfect righteousness; for what more acceptable offering can such persons make to God than themselves? But this question of purgatorial punishments we must defer to another time, to give it a more adequate treatment. (St. Augustine, City of God, Book 20, 25; further references to purgatory in this book occur at 20:26; 21:13, 16, 24, 26)

The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (pp. 1144-1145) provides an introductory overview:

St. Clement of Alexandria already asserts that those who, having repented on their deathbed, had no time to perform works of penance in this life, will be sanctified in the next by purifying fire (Stromateis, 7.6), a conception developed by Origen (Numbers, Hom. 15; J.P. Migne, PG, xii, 169 f.). . . . A more developed doctrine is taught by St. Ambrose, who asserts that the souls of the departed await the end of time in different habitations, their fate varrying acc. to their works, though some are already with Christ. The foundation of the medieval doctrine is found in St. Augustine, who holds that the fate of the individual soul is decided immediately after death, and teaches the absolute certainty of purifying pains in the next life (De Civ. Dei, xxi. 13, and ib., 24), whereas St. Caesarius of Arles already distinguishes between capital sins, which lead to Hell, and minor ones, which may be expurgated either by good works on earth or in Purgatory. This doctrine was sanctioned also by St. Gregory the Great . . .

Philip Schaff (as a “hostile witness” of sorts) sums up the consensus of the fathers and the early Church in this regard:

The majority of Christian believers, being imperfect, enter for an indefinite period into a preparatory state of rest and happiness, usually called Paradise (comp. Luke 23:41) or Abraham’s Bosom (Luke 16:23). There they are gradually purged of remaining infirmities until they are ripe for heaven, into which nothing is admitted but absolute purity. Origen assumed a constant progression to higher and higher regions of knowledge and bliss. (After the fifth or sixth century, certainly since Pope Gregory I., Purgatory was substituted for Paradise). . . .

Eusebius narrates that at the tomb of Constantine a vast crowd of people, in company with the priests of God, with tears and great lamentation offered their prayers to God for the emperor’s soul. Augustin calls prayer for the pious dead in the eucharistic sacrifice an observance of the universal church, handed down from the fathers. He himself remembered in prayer his godly mother at her dying request. . . .

These views of the middle state in connection with prayers for the dead show a strong tendency to the Roman Catholic doctrine of Purgatory, which afterwards came to prevail in the West through the great weight of St. Augustin and Pope Gregory I. . . .

Origen, following in the path of Plato, used the term “purgatorial fire,” by which the remaining stains of the soul shall be burned away; but he understood it figuratively, and connected it with the consuming fire at the final judgment, while Augustin and Gregory I. Transferred it to the middle state. The common people and most of the fathers understood it of a material fire . . . (History of the Christian Church, Vol. 2, Chapter XII, § 156. Between Death and Resurrection, 601, 603-605)

So much for the alleged “scant” history of purgatory in the Church fathers. . . .

Moreover, there is a strong argument indeed that can be made for purgatory from Holy Scripture. I have compiled no less than fifty passages that describe either purgatory or the processes of purging, cleansing, fire (either real or metaphorical), etc., that make up its essence. I’ve written several other papers as well about biblical indications for purgatory (one / two / three / four / five).

I’ve also written many times about scriptural support for prayers and penance for the dead (which pretty much presupposes purgatory) — which St. Paul did regarding Onesiphorus — (one / two / three / four / five / six).

There are all kinds of biblical arguments for purgatory: and very good ones, too. If Collins had been familiar with them, then he could have dealt with at least a few of these in his book. But he did not. That makes it a far less effective persuasive tool against Catholicism. To be impressive or successful in theological debate, one must deal with the best arguments an opponent can put up, not the worst, or none at all. Collins doesn’t even show that he is aware of them, let alone willing or able to take them on.

And the present shortcoming in this respect is by no means an isolated one in the book. In my previous post on the “Queen of Heaven” it was observed that Collins was either completely unaware of the considerable scriptural data regarding the Queen Mother in ancient Israel; or if aware, chose to utterly ignore what is clearly a relevant major (and biblical) Catholic rationale for its doctrine of Mary as Queen of Heaven.

***

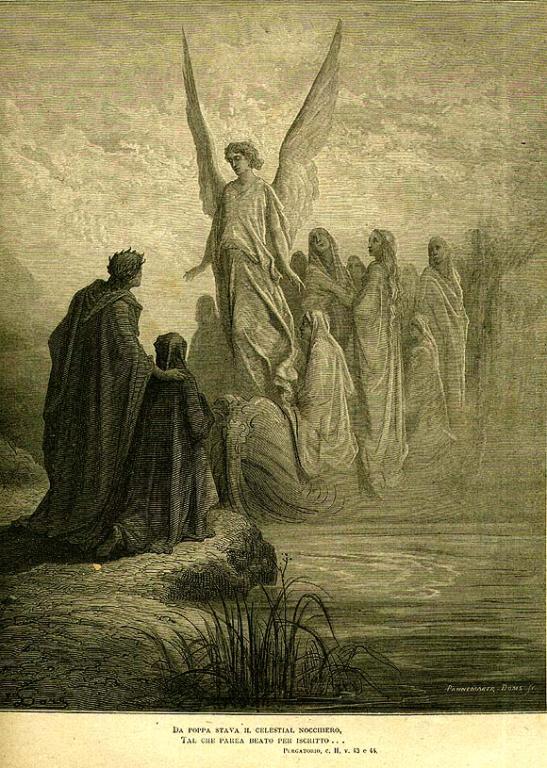

Photo credit: Illustration for Dante’s Purgatorio 02, by Gustave Doré (1832-1883) [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

***