“wildboar” (Steve Parks, a Lutheran pastor, or soon to be one) has written an interesting piece over at Here We Stand, a conservative Lutheran blog, entitled, Honor Thy Fathers? This short essay gets right to the heart of the matter, with regard to the nature of the Protestant Rule of Faith, or sola Scriptura.

Following Luther and Calvin, it states that while properly biblical tradition is helpful and worthy of respect, Holy Scripture is the sole infallible rule of faith, over against any Church or Tradition. I shall cite it in its entirety, and then respond below (very slightly revised, with italics added). I posted my questions initially on that blog. His words will be in blue. Later, “CPA”, another Lutheran, joined the discussion, and we engaged in lengthy dialogue. His words will be in green.

*****

It has been suggested that Lutherans often find themselves uncomfortably caught in the middle of many ecclesiastical debates. Indeed, much to our chagrin, conservative Lutherans have been labeled “too Catholic” by most Protestants and “too Protestant” by most Catholics. Perhaps this tension is best illustrated by the Lutheran approach to Scripture, and consequently, to the writings of the church fathers.

The Formula of Concord identifies the Old and New Testaments as the “the sole rule and standard according to which all dogmas together with [all] teachers should be estimated and judged” (The Formula of Concord, Ep. I.I, as found in Concordia Triglotta [Milwaukee, Wisconsin: Northwestern Publishing House, 1999], 777). Thus, Lutherans readily confess the doctrine which has come to be known as sola Scriptura. This, however, does not mean that Lutherans make the mistake committed by many Protestants of altogether ignoring the writings of the church fathers. Indeed, as Chemnitz notes:

The safest way to educate and remedy [our] own simplicity would be to consult the fathers of the church who, in the times of the pristine purity and learning directly after the apostles, were active in expounding [various subjects] publicly and with characteristic diligence, and to hear them as they conferred among themselves and shared their well-considered and pious opinions on the basis of God’s Word. (Martin Chemnitz, The Two Natures in Christ translated by J.A.O. Preus [St. Louis, Missouri: Concordia Publishing House, 1971], 19)

Far from contradicting the teaching of the Formula of Concord (which he helped author), Chemnitz immediately cautions:

However, the norm and rule of judgment must always be the voice of God as revealed in Scripture, to which all statements, even those of the most ancient scholars, must be subjected and according to which they must be examined and interpreted. Chemnitz, The Two Natures in Christ, 20)

In pithy fashion, Luther writes:

Whenever we see that the opinions of the fathers are not in agreement with Scripture, we respectfully bear with them and acknowledge them as our forefathers; but we do not on their account give up the authority of Scripture. (Martin Luther, Lectures on Genesis as found in Luther’s Works edited by Jaroslav Pelikan, Vol. 1 [St. Louis, Missouri: Concordia Publishing House, 1958], 122)

To state it succinctly, therefore, Lutherans believe that when the church fathers depart from the voice of Christ sounding forth in the Scriptures, we must depart from the teaching of the fathers.

As a preface, let me state that I like wildboar’s writings, and have complimented him on them.

My questions are:

1) Who determines whether the Fathers (generally or individually) are “biblical” and “right or wrong” based on a comparison with the Bible?

2) On what grounds does this standard have more authority than the Fathers whom it / his / her deems “non-biblical? So, for instance, if Chemnitz says that Augustine or Chrysostom or Ambrose or Irenaeus are “unbiblical” concerning thus-and-such, why should I accept his opinion over against that of these eminent Fathers whom he is critiquing?

3) Now, if you say that this is determined by a vote of Lutheran scholars or pastors or something (I don’t know what your answer would be; I’m just being hypothetical here), then how is that all that different from what Catholics do (i.e., applying some authority besides Scripture itself to authoritatively interpret Scripture, and correct or confirm expositors of it)?

4) How is that (the scenario in #3) still somehow sola Scriptura, while Catholic dogmatic pronouncements are not? What’s the practical difference (apart from Catholic considerations and claims of infallibility, where applicable, which is a clear difference)?

5) And how is accepting some Lutheran denominational pronouncement on which patristic statements are biblical and which are not, more intrinsically authoritative than (again) what occurs in the Catholic Church?

As readers can by now surmise, my position is that sola Scriptura inevitably breaks down as internally incoherent and inconsistent. The bottom-line question (when the issue is examined at with sufficient scrutiny) really becomes: on what grounds do we accept one exegetical / hermeneutical / dogmatic authority over another? Why choose Lutheran (or Reformed) interpretations over that of the Fathers, or of Catholicism or Orthodoxy?

This Lutheran argument is, in the end, either circular, or proves and establishes nothing, and is entirely arbitrary. If someone disagrees with that assessment, I would like to hear and understand why, based on answers to my questions and any other relevant considerations that could be brought to bear.

[I will probably paste your post and this reply on my blog, too, if that’s okay, because I think it’s a very important discussion, especially for Protestants to consider]

In Him,

Dave

CPA made a reply on the Here We Stand blog:

Dave, in practice for a great many issues (including most if not all of the ones that separate Roman Catholics and Augsburg Evangelicals) the problem is not nearly so involved as you make it. You write: “So, for instance, if Chemnitz says that Augustine or Chrysostom or Ambrose or Irenaeus are ‘unbiblical’ concerning thus-and-such, why should I accept his opinion over against that of these eminent Fathers whom he is critiquing?”

In so many cases, what you find on investigation is that patristic viewpoint is actually not based on sustained Biblical exegesis. When you go to the analysis, it’s just not there. Let’s take the issue of free will (which is one in which the fathers differ). St. Irenaeus says we have free will to turn or not to turn to God. St. Augustine denies that. Who is right? Your way of reasoning suggests that it is instantly a “he-said, she-said” problem, and so we need a single authority to decide.

In reality, however, even a cursory examination shows that while St. Augustine based his view on a serious, sustained engagement with the vital texts of Romans 9, St. Irenaeus did not (he used the Bible on other issues, but not on this, where he simply assumed a particular philosophical position–incompatibilism–and argued that lack of free will in things of God means lack of responsibility). Given that fact, sola scriptura instantly decides the issue: not so much that St. Irenaeus is wrong, but that he does not really have a viewpoint relevant to the issue. (That would be true of most of the rest of the fathers on this issue as well.)

Many similar examples could be produced as well.

Hi CPA,

It’s not at all certain that Augustine denied free will, in the sense that you (and standard reformed / Lutheran polemics) are claiming (or, additionally, that all Church historians agree that he did). I dealt with this question at great length in the following paper: “St. Augustine: Which Christian Body is Closer Theologically to His Teaching?: Reformed Protestants or Present-Day Catholics?”

So that is my answer to the particular alleged “counter-example” you have offered. Beyond that, you merely engage in more of the ultimately circular reasoning that I am critiquing, by stating:

In so many cases, what you find on investigation is that patristic viewpoint is actually not based on sustained Biblical exegesis. When you go to the analysis, it’s just not there.

First of all, this is your judgment. If others disagree (whether scholars or historical institutional Christian positions), we must still decide upon what basis to choose. You have made your argument. But you are not ultimately any kind of authority (nor am I). One has to accept the interpretation of a larger institution than themselves (for me, the Catholic church, for you, the Lutheran, and historic Protestantism to some extent).

Secondly, St. Irenaeus’ position is not rendered untrue simply because he personally may not have made elaborate exegetical arguments for it. Others may have, and there are other grounds for determining the truth besides exegesis, in the first place. All positions must be harmonious with the Bible; on that much we can all agree.

Conversely, Augustine may have been wrong in some of his arguments (i.e., assuming he denied free will). The Church has deemed double predestination and the denial of human free will (in a certain sense) to be erroneous positions. Individual Fathers, may, of course, be wrong on some things.

Thirdly, you have simply assumed (according to the notion perspicuity: itself severely flawed and questionable) that the Bible is clear on this question, so that it is a slam dunk for Augustine (as you interpret him) and against Irenaeus and others who take his position. But that is precisely what is at issue.

Some Christian traditions assert free will (while not denying predestination of the elect) and others deny it. We still have to choose. Why accept the historic Lutheran / Reformed position (of course, Melanchthon differed with Luther on this, so there is some amnbiguity)?

All you have accomplished, therefore, is:

1) assume that Augustine believes certain things (which are questionable).

2) assume that he is right and other fathers wrong, based on:

3) an unproven assumption of perspicuity, and

4) an unproven assumption that sola Scriptura (itself unproven and unbiblical and suffering from a host of internal inconsistencies) “instantly decides the issue.”

You’ve made several assumptions, that have to be proven, to have any weight.

In the end, I still contend that the bottom-line questions are precisely the ones I have asked. I am asking that a Lutheran make a straightforward attempt to give some sort of simple answers to my simple questions. After that, I would be happy to argue particulars, but we must grasp what our presuppositions are, and the difficulties therein (i.e., fundamental issues and premises), before rushing off to argue about what Augustine and Irenaeus believed on thus-and-so.

Wildboar’s argument was very broad and “presuppositional.” I answered in the same vein. I would like to see counter-replies to my honest (and I think, important) questions.

God bless,

Dave

CPA made a lengthy reply at Here We Stand, mostly about St. Augustine, with some repetition of his earlier points. I responded:

I want to discuss the presuppositional issues, not Augustine.

Not all patristic views must be based upon Scripture Alone. There is also Tradition and reason brought to bear. You’re presupposing sola Scriptura (as we would expect a Protestant to do, but that doesn’t make it compelling for anyone else).

And, of course, sola Scriptura isn’t taught in Scripture (where we would expect to find it if it is true, and is a statement about what all Christians should accept with regard to Scripture and its authority). So where does it come from? Well, it’s a tradition of men! Thus, this position reduces (quite ironically) to a non-biblical, arbitrary one, whereas it is made out to be the only viable position.

I’ll look to see if my questions were answered in the other posts.

Dave,

Let me pull back and outline where I am on Sola Scriptura, and why I keep focusing on “details”:

Right now, I believe the Lutheran understanding of Scripture to be correct. Where Lutheran interpretations differ from Catholic interpretations the latter seem to me to be incorrect. I also believe that I have a moral obligation to follow my understanding of Scripture; this follows from first of all what I believe to be a general obligation of honesty to be faithful in one’s interpretation of others’ words, and even more from it being God’s word which is in question. As a result I feel I cannot in conscience be a Catholic.

O.K., I’m sure you’ve heard this before. But if someone were to try to convince me to become Catholic they would have to do one of the following:

1) Convince me in detail that the Catholic interpretation of the disputed passages is the correct one.

or

2) Convince me that the apostles did really believe and ordain that the words they left in Scripture were to be authoritatively interpreted by their successors the bishops, esp. Peter’s successors in Rome.

or

3) Convince that no text can be rationally conclusive in the absence of a living authority to interpret it and if such a authority exists that no interpretation contrary to that authority’s interpretation can be convincing.

As I see it, 3) is what you argued for. I have put up a reply to it on Here We Stand. I find it completely unconvincing, and when taken seriously a deeply skeptical point of view. Catholic apologists would, I think, be better served by sticking to the specifically Christian arguments 1 or 2, rather than by the epistemological/hermeneutical argument of 3.

CPA then responded with another post at Here We Stand, entitled, “Does a Text, Any Text, Need an Authoritative Interpreter to Make Real the Moral Obligation to Interpret It Correctly?” I shall cite it (as is my custom) in its entirety and reply to his arguments. I thank him for the vigorous, thought-provoking reply. I always love to receive those:

Dave Armstrong has challenged Wildboar with the common assertion that sola scriptura cannot be valid, since it does not have an authoritative court to decide which interpretations of Scripture work.

Technically, that was not my particular argument here, though I would certainly maintain that an authoritative Church is necessary, since I think that is the biblical, Catholic, and historic Christian position, and the only non-circular one possible to take, given that same history and Holy Scripture. My concern was with, rather, the relative plausibility of claimants for proper interpretation of the Fathers, as noted in my question #5:

The bottom-line question (when looked at with sufficient scrutiny) really becomes: on what grounds do we accept one exegetical / hermeneutical / dogmatic authority over another?

To the possibility that Scripture might be read to prove a Church Father wrong he asks:

Again, this is an inaccurate portrayal of why I asked the questions. I don’t deny at all (nor does the Catholic position) that Scripture could disprove a position of a Church father. Chris acts as if I question the very “possibility.” Why he thinks that I would think this, would be, no doubt, a fascinating aside, but we’ll move ahead for now.

[at this point, my five questions, asked in the original post above, are cited]

Here’s my problem with this, and it is one I have stated before: the underlying assumption here is that Scripture as a written document cannot ultimately speak clearly enough to make us guilty from transgressing it without a human court of authority to enforce its statements with correct interpretation.

This can hardly be my “underlying assumption” because I don’t believe it in the first place! I stated my own view very precisely, in another paper of mine:

But is Scripture sufficient to refute Arianism on its own . . .? I think so, . . .

Nevertheless, I think it is also true that if a person was in a hypothetical situation where they knew absolutely nothing of Church history, Christian theology, and precedent in how these doctrines were and are thought about and derived from Scripture, and was tossed a Bible, that modalism (aka Sabellianism) and Arianism might seem as “plausible” to them as trinitarianism seemed. After all, the Trinity is not an easily grasped doctrine, and it is not immediately accessible to human reason. It is a revelation and mystery which must ultimately be accepted in faith (not to undermine its scriptural proofs).

So, while wholeheartedly agreeing with you that the case can be made by Scripture, I think we fool ourselves if we don’t recognize the role of Tradition and precedent as a strong influencing factor in how we all think. Most of us have grown up in cultures and/or households where trinitarianism and the Deity of Christ was taken for granted. It was the air we breathed.

But if one grew up in a secular context or was completely ignorant of historic theology, sure, I could see how they could grab a Bible and conclude that it taught Arianism or modalism (which is quite a bit more subtle). Of course, I agree that this would be an opinion based in ignorance of the totality of Scripture teaching and proper exegesis and hermeneutics and lack of understanding of difficult passages where commentary is most helpful. But one could still do it.

And again, in the same paper (emphasis added now):

As I have stated repeatedly, binding Church authority, is a practical necessity, given the propensity of men to pervert the true apostolic Tradition as taught in Scripture, whether it is perspicuous or not. The fact remains that diverse interpretations arise, and a final authority outside of Scripture itself is needed in order to resolve those controversies. This does not imply in the least that Scripture itself (rightly understood) is not sufficient to overcome the errors. It is only formally insufficient by itself.

. . . I write entire books and huge papers citing nothing but Scripture. It doesn’t mean for a second that I don’t respect the binding authority of the Catholic Church or espouse sola Scriptura. St. Athanasius made some extensive biblical arguments. Great. Making such arguments, doing exegesis, extolling the Bible, reading the Bible, discussing it, praising it, etc., etc., etc., are all well and good (and Catholics agree wholeheartedly); none of these things, however, reduce to or logically necessitate adoption of sola Scriptura as a formal principle, hard as that is for some people to grasp.

These sorts of clarifications are extremely important if one is to understand my position, and that of the Catholic Church (and, I would say — provocatively, no doubt –, also the view of the Bible and the Fathers). If a reader doesn’t grasp these distinctions and positions, then I urge them to cease reading this dialogue right now, because nothing good can come of it if the two opposing positions are not properly comprehended. I can only hope that my opponent(s) will better understand the Catholic position after my explanation of it in this regard.

I think it’s a good thing, because here it is shown that there is more agreement than many on either side suspect. This is good news. There are differences remaining concerning Bible and Tradition, but there are also exciting areas of agreement, if only this could be more widely known.

(Note, frequently the argument is rendered with the phrase in bold as “settle disputes,” which makes it absurd. Obviously a book by itself cannot stop me from misinterpreting itself. But it can, I contend, be sufficiently clear for me to be guilty before God for misinterpreting it.

I agree. Yet, sadly, the problem comes when different bodies start disagreeing on what is clear and what isn’t in Scripture, and what Scripture in fact teaches regarding thus-and-so possible heresy. Even if Scripture is in fact clear on a matter (say that God declares that it was perfectly clear, when we get to heaven and ask Him about it, which would be absolute certainty), that doesn’t mean that Christians will agree. And since contradiction necessarily involves error, it is important for all of us to have some way of resolving these disputes.

And that brings us right back to Church authority and/or some form of tradition. It’s unavoidable. It’s inevitable. Anyone who denies this is living in unreality and self-delusion. All Christians have to resolve this dilemma in some fashion. The solutions differ, and that is what we are debating presently, but the problem is the same for all.

So the issue between us is: Am I morally obligated to follow the Scriptures as I understand them, even when an authoritative church body interprets them differently? I say yes, Armstrong says no.

It’s not quite that simple. If the Church I am in clearly contradicts Scripture, then of course, I am obligated to leave in protest, and am fully justified in doing so. This would be the case, e.g., in the Episcopal Church USA (ECUSA), where a practicing homosexual bishop was ordained. That is absolutely contrary to Scripture, and so one must follow the Scripture and conclude that this body is not doing so and must be opposed.

What Catholics say is that there is such a Church (historical and institutional) which is uniquely guided by the Holy Spirit towards true doctrine and morals (Protestants deny this), and that Christians are indeed obligated to follow that Church in cases where it has authoritatively decided what is true and what is not true, in theology. We believe this in faith: that God has protected the Catholic Church from error, because He wants one Church, with authority, not hundreds, which contradict each other and cause endless confusion for the Christian flock. We think it is grounded in revelation and perfectly defensible, even from history.

I certainly accept however that I am also morally obligated to test my understanding against those of all other Christians, and especially those of distinguished reputation and holiness, and not to disagree with them without such testing.)

This gets back to your problem of why you should accept one interpretation over another, when there are disagreements.

I contend that that underlying assumption carries with it dangerous skepticism about the power of language. I know Dave Armstrong is not himself a skeptic, but I think that is the implication of his position.

It’s not, because you have greatly misunderstood my premises, as shown. Thus, your counter-argument will soon collapse (as I am in the process of showing). I don’t blame you for that: these are complicated matters, and we don’t know each other all that well, but now having been informed of my beliefs, you will have to modify your argument and come up with something else.

Let’s use an analogy. I believe Roe vs. Wade is bad constitutional law. Quite apart from the issue of abortion itself, I believe it has no legitimate basis in the language of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Absolutely. I agree.

Let’s say I cite people who agree with me, like Stephen Carter. Now, what if someone were to say: the Supreme Court has said you are wrong, therefore as an honest man you are in conscience bound to accept that the Fourteenth Amendment doesn’t say what you think it does. Amend the Fourteenth Amendment if you like, but recognize that the Constitution, like any text, needs a living authority to interpret it before it can be a legal norm at all. The Supreme Court is that living authority, and that living authority disagrees with you.

The Supreme Court is not protected by the charism of infallibility, by the Holy Spirit. The Bible teaches that God’s law is above human law, and that there are times to obey God rather than man, when the two are in conflict. That’s why I was in the pro-life Rescue movement (in terms of the legal rationale). I broke laws because they were immoral laws, and I did that in order to literally save babies’ lives. So the analogy is fundamentally flawed from the outset. That’s too bad, because I love analogies . . . :-)

It’s true that the Constitution needs to be interpreted, as does law in general, but the present question is whether the Christian Church was intended by God to be infallible or not, or if Scripture is the only infallible authority (sola Scriptura). The Supreme Court has never claimed infallibility. It can reverse itself, and the people can in effect reverse its rulings by constitutional amendment. Hence, in the Dred Scott case, slavery was upheld, but by constitutional amendment, it was abolished. The people were right; the Court wrong. It’s currently hideously wrong on abortion. It doesn’t follow that no Church body could ever be infallible.

Couldn’t that person use exactly Dave Armstrong’s arguments?

No, and I’ll now show why (though the “fatal blow” to your argument has already been delivered).

1) Who determines whether the judicial precedents are “constitutional” and “legitimate” based on a comparison with the Constitution?

Judges. This is indeed a parallel with the Church’s authority to interpret Christian doctrine as orthodox or heretical. But the disanalogy comes with the divinely-instituted gift of infallibility, which earthly judges do not have. There is such a conceivable thing as a Christian Church which could always be right, on the major matters of faith and morals (which is where we claim the highest level of infallibility. This is no more implausible, in fact, than an infallible, “God-breathed” Bible written by quite-fallible and sinful men. If that is a fact (as we all believe) then an infallible Church can certainly be at least a possible fact. It’s not implausible at all, and makes perfect sense.

2) On what grounds does this standard have more authority than the preceding legal decisions whom it / his / her deems “unconstitutional”? So, for instance, if Carter says that the views of Thurgood Marshall or Harry Blackmun or Lawrence Tribe are “unconstitutional” concerning Roe vs. Wade, why should I accept his opinion over against that of these eminent jurists whom he is critiquing?

By no criteria other than the legal reasoning, because they are all on the same ground, in the epistemological sense (if I may use that word with reference to legal matters). What my #2 question was designed to show was that claims of being “biblical” still reduce to human tradition at some point; therefore it is a matter of pitting one tradition against another. I think that for most people, a comparison of Augustine and Chemnitz is almost laughable. There is no comparison. But this is what is made necessary by sola Scriptura.

You say that you accept a Father insofar he is “biblical.” Catholics agree that all teachings ought to be harmonious with Scripture. We don’t disagree so far. What we disagree on is the notion that an individual theologian in the 16th century, whether Chemnitz or Luther or Calvin, ought to be deemed (on what grounds, no one will tell me) a “super-authority” ( I have called Luther, notoriously, a “Super-Pope” for perfectly sensible reasons) over against the consensus of the Church Fathers, or even one eminent Father.

You say the criterion is the Bible. But then the question immediately becomes “whose interpretation of the Bible?” And that question is necessary and supremely relevant because in a practical sense (not in an intrinsic sense, as explained in my citations from another paper, above), Scripture has not always been clear (or clearly understood, one might say), historically-speaking. So your position reduces to: “the clear teaching of Scripture on topic x [unspoken premise: because this is what Chemnitz said Scripture taught].”

It’s a huge difficulty as soon as there is disagreement, and we all know that that is rampant in Protestant ranks. The Catholic Church has no such problem because they have the means to resolve the problem, and to do so with unquestionable authority. The Protestant doesn’t believe that is possible, because they no longer have faith that God is able to preserve an infallible Church.

I’ve written about the radical circularity of both sola Scriptura and perspicuity:

Fictional Dialogue on Sola Scriptura

The Logical Circularity and Hidden Premises of Sola Scriptura and Private Judgment

Sola Scriptura is Self-Defeating and False if Not in the Bible

The Perspicuity (Clearness) of Scripture

3) Now, if you say that this is determined by a vote of pro-life/originalist scholars or jurists or something (I don’t know what your answer would be; I’m just being hypothetical here), then how is that all that different from what Roe vs. Wade supporters do (i.e., applying some authority besides the Constitution itself – i.e. the Supreme Court – to authoritatively interpret the Constitution, and correct or confirm expositors of it?)

The point of my #3 was that both sides utilize tradition of some sort. That is true here, too. There was a pro-life tradition which was formerly the mainstream in law, and now the opposite is the case. My rhetorical (but simultaneously extremely practical and realistic) question was meant to defeat the fallacious notion that adherents of sola Scriptura somehow stand outside all traditions. They do not. Therefore, it is proper and necessary to ask why we should accept Luther’s or Melanchthon’s or Chemnitz’s opinions over the more ancient, agreed-upon ones of the consensus of the Fathers and of the Catholic Church.

4) How is that (the scenario in #3) still somehow just following the Constitution, while Supreme Court dogmatic pronouncements are not? What’s the practical difference (apart from the Supreme Court’s position as the arbiter of the law of the land, which is a clear difference)?

#4 was a variant of #3. Since you have misunderstood the nature of my premises and my argument, then this is ultimately much ado about nothing. Some analogies still hold, in terms of what I was actually arguing, but the larger analogy fails because it presupposed that I presupposed what I did not presuppose.

5) And how is accepting some pro-life or originalist position on which constitutional statements are legitimate and which are not, more intrinsically authoritative that (again) what occurs in the Supreme Court?

Because the Supreme Court ought to be based on the Higher Court of God’s Law. If it is not, it can be dissented against. The Catholic Church has shown itself to have far and away the best historical credentials and moral and biblical faithfulness, in its teachings, to be rightly regarded as “the Church” in a unique sense. No Protestant body can withstand this biblical and historical scrutiny. But that takes us off into far different subject matter . . . The Catholic Church is authoritative because it was founded by Jesus Christ, and has continued with an unbroken apostolic succession.

As readers can by now surmise, my position is that allowing individuals like Stephen Carter to have opinions on constitutional law contrary to existing Supreme Court precedents inevitably breaks down as internally incoherent and inconsistent. The bottom-line question (when looked at with sufficient scrutiny) really becomes: on what grounds do we accept one legal / hermeneutical / juristic authority over another? Why choose Carter’s interpretations over that of the 1970s jurists, or of the Supreme Court today?

Because it is consistent with God’s law, which is pro-life. One can dissent against man’s laws when they are immoral, as in this instance. But if indeed there is an infallible Church, by God’s decree, man cannot dissent against its teachings. Thus, it is my task and the Catholic task to make various arguments suggesting that the Catholic Church is indeed what she claims to be.

Throw in reminders that I’m no constitutional scholar and that it would be arrogant for me to assume that I know better than all those learned justices and the argument is complete: an individual who wants to be intellectually honest is morally obligated to defer to the Supreme Court’s authoritative interpretation of the constitution. Any denial of that body’s definite decisions is intellectually incoherent and inconsistent.

Not at all, because the analogy fails, per the above reasoning.

In fact, I’ve heard this argument many times specifically drawn vis a vis Roe vs. Wade and to me, it has always seemed absurd.

I agree. I’m not a legal positivist, anymore than I am a logical positivist. Man’s law is not the highest standard.

Quite apart from whether the Supreme Court is or is not infallible, the idea that the existence of dispute over interpretation of a text whose authority they accept means that someone does not have a moral obligation to follow their conscience in interpretation seems wrong on the face of it. Which means Dave Armstrong’s argument too must be wrong.

Catholics believe that one must follow their conscience, but also that it must be an informed conscience. So. e.g., if someone claims that they must conscientiously practice contraception (or abortion, for that matter, to follow the attempted analogy), we say that this is an improperly informed conscience, because revelation and Church teaching have taught that the practice is a grave sin. The same applies to the homosexual argument today. They appeal to Scripture, and they claim it is clear.

But the slam-dunk against this serious error is historic Christian teaching. Scripture is clear on the matter, but they don’t think so, so we have to appeal to authority. Whole Protestant denominations are self-destructing over this, because they have forfeited moral authority and caved in to the fashionable cultural zeitgeist. But the Catholic Church is where she has always been: opposed to homosexual practice as intrinsically disordered and a grave sin.

If Armstrong’s argument makes sense for the particular text known as the Bible, why doesn’t it work for the particular text known as the Constitution?

Because the Constitution is not divinely-inspired and the Supreme Court is not a divinely-protected infallible institution.

Armstrong’s argument makes no reference to the Bible’s nature as a religious text, so that can’t be the issue.

All orthodox Christians accept Scripture as inspired. Yawn . . .

He appears to be arguing for a living authority not because the Catholic Church has claimed to be that authority, but because such an authority is needed by the nature of Bible as a mere text, one which in practice has been interpreted differently by different people.

Not because of the intrinsic unclearness in the main of Scripture (which is not the Catholic position, rightly-understood), but because (for various reasons) people will in fact interpret it differently, and therefore we need a mechanism to achieve doctrinal and ecclesiological unity (which is presupposed as a reality in Scripture, especially in St. Paul.

And if that’s the case, then his argument applies to all texts.

It can’t by the nature of the case, because only one text is divinely-inspired, thus making it sui generis.

Which is obviously not held by anyone, hence Dave Armstrong’s argument is wrong.

CPA’s attempted refutation is wrong because it misunderstands my argument and the Catholic position, and offers failed “analogies”. He will have to find another way to cogently, plausibly answer my five questions.

***

(originally 5-29-05)

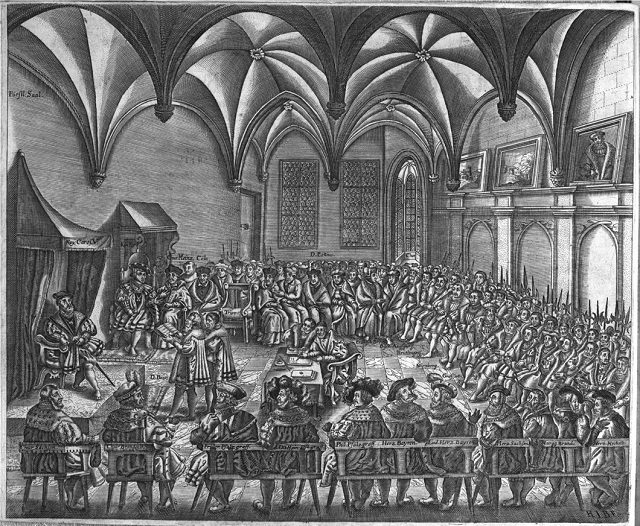

Photo credit: Diet of Augsburg, by Christian Beyer (1482-1535) [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

***