This is an installment of a series of replies (see the Introduction and Master List) to much of Book IV (Of the Holy Catholic Church) of Institutes of the Christian Religion, by early Protestant leader John Calvin (1509-1564). I utilize the public domain translation of Henry Beveridge, dated 1845, from the 1559 edition in Latin; available online. Calvin’s words will be in blue. All biblical citations (in my portions) will be from RSV unless otherwise noted.

Related reading from yours truly:

Biblical Catholic Answers for John Calvin (2010 book: 388 pages)

A Biblical Critique of Calvinism (2012 book: 178 pages)

Biblical Catholic Salvation: “Faith Working Through Love” (2010 book: 187 pages; includes biblical critiques of all five points of “TULIP”)

*****

IV, 8:11-15

***

CHAPTER 8

*

11. Answer to the Papistical arguments for the authority of the Church. Argument, that the Church is to be led into all truth. Answer. This promise made not only to the whole Church, but to every individual believer.

First, let us hear by what arguments they prove that this authority was given to the Church, and then we shall see how far their allegations concerning the Church avail them.

Great! Let’s do that, and let’s especially look to see what allegedly superior alternative Calvin offers.

The Church, they say, has the noble promise that she will never be deserted by Christ her spouse, but be guided by his Spirit into all truth. But of the promises which they are wont to allege, many were given not less to private believers than to the whole Church. For although the Lord spake to the twelve apostles, when he said, “Lo! I am with you alway, even unto the end of the world” (Mt. 28:20); and again, “I will pray the Father, and he shall give you another Comforter, that he may abide with you for ever: even the Spirit of truth” (John 14:16, 17), he made these promises not only to the twelve, but to each of them separately, nay, in like manner, to other disciples whom he already had received, or was afterwards to receive.

That will only compound Calvin’s epistemological problems, if he wishes to minimize the corporate nature of Christianity (as Protestantism always tends to do, by nature). Then he will have to show how individuals possess the fullness of truth, over against institutions, and that opens up a bunch of cans of worms that have no resolution whatsoever within the Protestant presuppositional framework. Calvin has not yet denied the doctrine of a teaching, disciplining Church, so in a way he is at cross-purposes with himself in making these points.

When they interpret these promises, which are replete with consolation, in such a way as if they were not given to any particular Christian but to the whole Church together, what else is it but to deprive Christians of the confidence which they ought thence to have derived, to animate them in their course?

This is ludicrous, because if Church-wide belief is rejected, why is it that Protestants (including Calvin himself) maintained creeds and confessions? Obviously there is a sense in which the individual has to yield to truths larger than he himself, in his little subjective world, or else we’d have as many creeds as there are Christian brains, just as Luther disdainfully observed, about “as many sects as there are heads.” This line of reasoning goes nowhere. It’s doomed to failure, every time.

I deny not that the whole body of the faithful is furnished with a manifold variety of gifts, and endued with a far larger and richer treasure of heavenly wisdom than each Christian apart;

Good; but his argument ultimately undercuts these truths.

nor do I mean that this was said of believers in general, as implying that all possess the spirit of wisdom and knowledge in an equal degree: but we are not to give permission to the adversaries of Christ to defend a bad cause, by wresting Scripture from its proper meaning.

Meaning according to whom? Calvin? If he decides, then his dogmatism is even more objectionable than what he decries as Catholic dogmatism, because it is both more arbitrary and dogmatic, insofar as he is just one man, acting alone (whereas even popes act according to prior tradition and the current Mind of the Church). And (quite obviously) we have to figure out who is right when Protestants disagree (as they always, invariably do). Who has the Spirit? Who is “unbiblical”? Does Calvin’s opinions trump even Luther’s when they disagree?

Omitting this, however, I simply hold what is true—viz. that the Lord is always present with his people, and guides them by his Spirit. He is the Spirit,

not of error, ignorance, falsehood, or darkness, but of sure revelation, wisdom, truth, and light, from whom they can, without deception, learn the things which have been given to them (1 Cor. 2:12); in other words, “what is the hope of their calling, and what the riches of the glory of their inheritance in the saints” (Eph. 1:18). But while believers, even those of them who are endued with more excellent graces, obtain in the present life only the first-fruits, and, as it were, a foretaste of the Spirit, nothing better remains to them than, under a consciousness of their weakness, to confine themselves anxiously within the limits of the word of God, lest, in following their own sense too far, they forthwith stray from the right path, being left without that Spirit, by whose teaching alone truth is discerned from falsehood. For all confess with Paul, that “they have not yet reached the goal” (Phil. 3:12). Accordingly, they rather aim at daily progress than glory in perfection.But folks who are equally led by the Spirit do in fact arrive at different interpretations of this Scripture. Authoritative dogma and boundaries are always required, for that reason. God knew this, which is why He set up an authoritative teaching Church, not a system of individualistic subjectivism, which is far more a secular Enlightenment or Romantic or eastern religious concept than a biblical one.

12. Answers continued.

But it will be objected, that whatever is attributed in part to any of the saints, belongs in complete fulness to the Church. Although there is some semblance of truth in this, I deny that it is true. God, indeed, measures out the gifts of his Spirit to each of the members, so that nothing necessary to the whole body is wanting, since the gifts are bestowed for the common advantage. The riches of the Church, however, are always of such a nature, that much is wanting to that supreme perfection of which our opponents boast.

More lack of faith . . . we must never seek for the ideal that is discussed in Scripture. God is too weak to accomplish that with sinful men, so thinks Calvin (and indeed, all Protestants, by virtue of their system and what they deny).

Still the Church is not left destitute in any part, but always has as much as is sufficient, for the Lord knows what her necessities require. But to keep her in humility and pious modesty, he bestows no more on her than he knows to be expedient.

This is another way of saying that “God is not powerful enough to bring about doctrinal certainty”.

I am aware, it is usual here to object, that Christ hath cleansed the Church “with the washing of water by the word: that he might present it to himself a glorious Church, not having spot or wrinkle” (Eph. 5:26, 27), and that it is therefore called the “pillar and ground of the truth” (1 Tim. 3:15). But the former passage rather shows what Christ daily performs in it, than what he has already perfected. For if he daily sanctifies all his people, purifies, refines them, and wipes away their stains, it is certain that they have still some spots and wrinkles, and that their sanctification is in some measure defective.

Catholics don’t deny this, but we also don’t deny, as Calvin does, that the goal and the ideal is always there to progress toward.

How vain and fabulous is it to suppose that the Church, all whose members are somewhat spotted and impure, is completely holy and spotless in every part?

How is that any more objectionable than Calvin’s own imputed justification, in which God declares someone who is obviously still a sinner, righteous? This is a rather strange argument for Calvin, of all people, to make. He’s the one who formally separated sanctification from justification and from salvation itself.

It is true, therefore, that the Church is sanctified by Christ, but here the commencement of her sanctification only is seen; the end and entire completion will be effected when Christ, the Holy of holies, shall truly and completely fill her with his holiness. It is true also, that her stains and wrinkles have been effaced, but so that the process is continued every day, until Christ at his advent will entirely remove every remaining defect.

And, by the same token, and by analogy, the same applies to the individual. It is Catholics who teach progressive sanctification as part and parcel of justification, but Calvin denies that. So his argument is again at cross-purposes with itself.

For unless we admit this, we shall be constrained to hold with the Pelagians, that the righteousness of believers is perfected in this life:

Pelagians denied the absolute necessity of God’s grace to accomplish righteousness and salvation. Catholics do not (as Calvin often wrongly denies).

like the Cathari and Donatists we shall tolerate no infirmity in the Church.

These groups were condemned by the Catholic Church, so it is odd for Calvin to attempt to make them similar to Catholicism.

The other passage, as we have elsewhere seen (chap. 1 sec. 10), has a very different meaning from what they put upon it. For when Paul instructed Timothy, and trained him to the office of a true bishop, he says, he did it in order that he might learn how to behave himself in the Church of God. And to make him devote himself to the work with greater seriousness and zeal, he adds, that the Church is the pillar and ground of the truth. And what else do these words mean, than just that the truth of God is preserved in the Church, and preserved by the instrumentality of preaching; as he elsewhere says, that Christ “gave some, apostles; and some, prophets; and some, evangelists; and some, pastors and teachers;” “that we henceforth be no more children, tossed to and fro, and carried about with every wind of doctrine, by the sleight of men, and cunning craftiness, whereby they lie in wait to deceive; but, speaking the truth in love, may grow up into him in all things, who is the head, even Christ”? (Eph. 4:11, 14, 15) The reason, therefore, why the truth, instead of being extinguished in the world, remains unimpaired, is, because he has the Church as a faithful guardian, by whose aid and ministry it is maintained.

Indeed! This is a good statement, but Calvin fails to consistently apply it. He asserts it here, but fights it somewhere else, and often he does both within the span of a few paragraphs.

But if this guardianship consists in the ministry of the Prophets and Apostles, it follows, that the whole depends upon this—viz. that the word of the Lord is faithfully preserved and maintained in purity.

Yes; it requires faith that God can bring this about, even though He is working with sinful men. Calvin lacks that faith. Catholics who accept all that the Church teaches possess it.

13. Answers continued.

And that my readers may the better understand the hinge on which the question chiefly turns, I will briefly explain what our opponents demand, and what we resist. When they deny that the Church can err, their end and meaning are to this effect: Since the Church is governed by the Spirit of God, she can walk safely without the word; in whatever direction she moves, she cannot think or speak anything but the truth, and hence, if she determines anything without or beside the word of God, it must be regarded in no other light than if it were a divine oracle.

The Catholic Church doesn’t create dogmas with no regard for Scripture. If Calvin wishes to assert the charge, why doesn’t he document it? But we’ve seen again and again that he doesn’t trouble himself to do that. It’s not necessary to do in propagandizing efforts. Mere statements suffice, whether true or false. People will believe them if they are unwilling or unable to do their own independent research, and above all, if they are predisposed to be hostile towards the Catholic Church, as Calvin is.

If we grant the first point—viz. that the Church cannot err in things necessary to salvation—

For a change, Calvin makes a necessary qualification of the Catholic claim to infallibility.

our meaning is, that she cannot err, because she has altogether discarded her own wisdom, and submits to the teaching of the Holy Spirit through the word of God. Here then is the difference. They place the authority of the Church without the word of God;

That is casually assumed without being demonstrated. We make no such dichotomy. Calvin does because he thinks in “either/or” terms: for him, if there is true Church authority, this must somehow inexorably be opposed to Scripture in some essential fashion. It’s simply not true.

we annex it to the word, and allow it not to be separated from it.

Again, this remains to be proven. Calvin makes the claim, but lots of folks folks make lots of claims. The proof is in the pudding.

And is it strange if the spouse and pupil of Christ is so subject to her lord and master as to hang carefully and constantly on his lips? In every well-ordered house the wife obeys the command of her husband, in every well-regulated school the doctrine of the master only is listened to. Wherefore, let not the Church be wise in herself, nor think any thing of herself, but let her consider her wisdom terminated when he ceases to speak.

Now Jesus the Head is set against the Body of Christ, the Church. That makes a lot of sense? Obviously, they work together, however one construes the Church. But Calvin must create a false dichotomy. Jesus is Head of the Church; therefore the pope cannot be an earthly head. Jesus is Head of the Church; therefore, His Body, the Church, must be at odds with Him, etc.

In this way she will distrust all the inventions of her own reason; and when she leans on the word of God, will not waver in diffidence or hesitation but rest in full assurance and unwavering constancy.

Amen! Competing Protestant sects sure do not exhibit a characteristic of “constancy,” do they?

Trusting to the liberal promises which she has received, she will have the means of nobly maintaining her faith, never doubting that the Holy Spirit is always present with her to be the perfect guide of her path. At the same time, she will remember the use which God wishes to be derived from his Spirit. “When he, the Spirit of truth, is come, he will guide you into all truth” (John 16:13). How? “He shall bring to your remembrance all things whatsoever I have said unto you.” He declares, therefore, that nothing more is to be expected of his Spirit than to enlighten our minds to perceive the truth of his doctrine. Hence Chrysostom most shrewdly observes, “Many boast of the Holy Spirit, but with those who speak their own it is a false pretence. As Christ declared that he spoke not of himself (John 12:50; 14:10), because he spoke according to the Law and the Prophets; so, if anything contrary to the Gospel is obtruded under the name of the Holy Spirit, let us not believe it. For as Christ is the fulfilment of the Law and the Prophets, so is the Spirit the fulfilment of the Gospel” (Chrysost. Serm. de Sancto et Adorando Spiritu.) Thus far Chrysostom. We may now easily infer how erroneously our opponents act in vaunting of the Holy Spirit, for no other end than to give the credit of his name to strange doctrines, extraneous to the word of God,

Again he assumes what he needs to prove . . . it’s very easy to “argue”: “my opponent advocates a pack of lies.” It’s the easiest thing in the world to claim. But to prove that each disputed belief is a falsehood and a lie is another thing entirely. Often Calvin refuses to even attempt the latter. He’ll make the charge without the slightest attempt at proof.

whereas he himself desires to be inseparably connected with the word of God; and Christ declares the same thing of him, when he promises him to the Church. And so indeed it is. The soberness which our Lord once prescribed to his Church, he wishes to be perpetually observed. He forbade that anything should be added to his word, and that anything should be taken from it. This is the inviolable decree of God and the Holy Spirit, a decree which our opponents endeavour to annul when they pretend that the Church is guided by the Spirit without the word.

Who ever claimed that the Catholic Church was somehow opposed to the Bible? I’d love to see that demonstration, but as usual, Calvin does not provide us with evidence of his claim. This portion is remarkably inept and inadequate. I can’t see that anyone would be impressed with it, except the one who is already a “true (Calvinist) believer” and inclined to a prior anti-Catholicism.

Here again they mutter that the Church behoved to add something to the writings of the apostles, or that the apostles themselves behoved orally to supply what they had less clearly taught, since Christ said to them, “I have yet many things to say unto you, but ye cannot bear them now” (John 16:12), and that these are the points which have been received, without writing, merely by use and custom. But what effrontery is this?

There is plenty of evidence in Scripture that there were traditions passed down, not all of which were contained in Scripture itself. I’ve already noted that, with links to hard evidences of same, and so won’t repeat myself.

The disciples, I admit, were ignorant and almost indocile when our Lord thus addressed them, but were they still in this condition when they committed his doctrine to writing, so as afterwards to be under the necessity of supplying orally that which, through ignorance, they had omitted to write? If they were guided by the Spirit of truth unto all truth when they published their writings, what prevented them from embracing a full knowledge of the Gospel, and consigning it therein?

Inspiration works despite the shortcomings of the instrument used.

But let us grant them what they ask, provided they point out the things which behoved to be revealed without writing. Should they presume to attempt this, I will address them in the words of Augustine, “When the Lord is silent, who of us may say, this is, or that is? or if we should presume to say it, how do we prove it?” (August. in Joann. 96)

Yes; that is true as a general statement. It doesn’t prove that there is no such thing as oral tradition. Augustine accepts oral tradition himself, after all:

[T]he custom, which is opposed to Cyprian, may be supposed to have had its origin in apostolic tradition, just as there are many things which are observed by the whole Church, and therefore are fairly held to have been enjoined by the apostles, which yet are not mentioned in their writings. (On Baptism, 5, 23:31; NPNF 1, IV, 475)

[I]f you acknowledge the supreme authority of Scripture, you should recognise that authority which from the time of Christ Himself, through the ministry of His apostles, and through a regular succession of bishops in the seats of the apostles, has been preserved to our own day throughout the whole world, with a reputation known to all. (Reply to Faustus the Manichaean, 33:9; NPNF 1, Vol. IV, 345)

And if any one seek for divine authority in this matter, though what is held by the whole Church, and that not as instituted by Councils, but as a matter of invariable custom, is rightly held to have been handed down by apostolical authority, still we can form a true conjecture of the value of the sacrament of baptism in the case of infants. (On Baptism, 4, 24, 31; NPNF 1, Vol. IV, 61)

Good question!

Every child knows that in the writings of the apostles, which these men represent as mutilated and incomplete, is contained the result of that revelation which the Lord then promised to them.

Catholics do not do this. Scripture often points to traditions outside of itself, that are yet true. Therefore, to hold such a view is not to hold to a “mutilated and incomplete” Bible. It is to hold to all that the Bible itself asserts. The Protestant, like Calvin, who denies that there is such a thing as a Tradition described and fully accepted in Scripture, is the one who is mutilating Scripture, because he selectively disbelieves part of that same Scripture. He doesn’t accept all of it, in its totality. He picks and chooses (the literal meaning of “heresy”).

15. Argument founded on Mt. 18:17. Answer.

What, say they, did not Christ declare that nothing which the Church teaches and decrees can be gainsayed, when he enjoined that every one who presumes to contradict should be regarded as a heathen man and a publican? (Mt. 18:17.) First, there is here no mention of doctrine, but her authority to censure, for correction is asserted, in order that none who had been admonished or reprimanded might oppose her judgment.

I agree, with regard to this passage.

But to say nothing of this, it is very strange that those men are so lost to all sense of shame, that they hesitate not to plume themselves on this declaration. For what, pray, will they make of it, but just that the consent of the Church, a consent never given but to the word of God, is not to be despised? The Church is to be heard, say they. Who denies this? since she decides nothing but according to the word of God.

This is a clever use of the redefined notion of “Church” that Calvin has brought in. In effect, he argues: “No one is denying Church authority because the Church is what I now say it is; therefore it is true and to be followed.”

If they demand more than this, let them know that the words of Christ give them no countenance. I ought not to seem contentious when I so vehemently insist that we cannot concede to the Church any new doctrine; in other words, allow her to teach and oracularly deliver more than the Lord has revealed in his word.

Catholics agree insofar as we believe in material sufficiency of Scripture and the completeness of the apostolic deposit. We disagree insofar as we think there is development of existing, scriptural doctrines, and infallible Church authority.

Men of sense see how great the danger is if so much authority is once conceded to men.

Here again is the hostility to the idea of God using sinners as His instruments, for His purposes. Calvin doesn’t have faith enough to believe that God could do that. And so he has to radically reshape the doctrine of the Church, to reflect his own lack of faith in God’s power and promises.

They see also how wide a door is opened for the jeers and cavils of the ungodly, if we admit that Christians are to receive the opinions of men as if they were oracles.

Every writer of Scripture was an oracle because he wrote inspired words. If one can believe in that miracle, as Calvin does, the gift of infallibility requires less faith. Yet he rejects the latter, as it it were at all impossible for God to accomplish. Apostles already spoke with extraordinary authority. Why not the Church? Why does Calvin not grasp these elementary factors?

We may add, that our Saviour, speaking according to the circumstances of his times, gave the name of Church to the Sanhedrim, that the disciples might learn afterwards to revere the sacred meetings of the Church. Hence it would follow, that single cities and districts would have equal liberty in coining dogmas.

This is more convoluted reasoning. The Sanhedrin governed all of Israel, not just Jerusalem. Jesus acknowledged their authority, even over Christians (Matthew 23:1-3). He didn’t say they could “coin dogmas.” The Catholic Church develops doctrine, and at length makes more particulars binding, so as to protect the faithful from heresy. Calvin has no objection to that when it regards a doctrine he accepts: like the Holy Trinity. He only starts disliking it when it entails Catholic doctrines that he doesn’t like.

(originally 7-6-09)

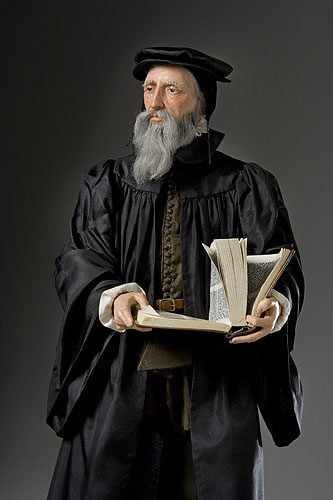

Photo credit: Historical mixed media figure of John Calvin produced by artist/historian George S. Stuart and photographed by Peter d’Aprix: from the George S. Stuart Gallery of Historical Figures archive [Wikimedia Commons / Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license]

***