This is an installment of a series of replies (see the Introduction and Master List) to much of Book IV (Of the Holy Catholic Church) of Institutes of the Christian Religion, by early Protestant leader John Calvin (1509-1564). I utilize the public domain translation of Henry Beveridge, dated 1845, from the 1559 edition in Latin; available online. Calvin’s words will be in blue. All biblical citations (in my portions) will be from RSV unless otherwise noted.

Related reading from yours truly:

Biblical Catholic Answers for John Calvin (2010 book: 388 pages)

A Biblical Critique of Calvinism (2012 book: 178 pages)

Biblical Catholic Salvation: “Faith Working Through Love” (2010 book: 187 pages; includes biblical critiques of all five points of “TULIP”)

*****

IV, 17:12-15

***

CHAPTER 17

OF THE LORD’S SUPPER, AND THE BENEFITS CONFERRED BY IT.

I now come to the hyperbolical mixtures which superstition has introduced.

It’s quite comical for Calvin to rail against “superstition” — given all the fictional and illogical, incoherent innovations he himself has introduced . . .

Here Satan has employed all his wiles, withdrawing the minds of men from heaven, and imbuing them with the perverse error that Christ is annexed to the element of bread.

That is, the biblical, apostolic, patristic, and historic Catholic “error” . . . (we must place things in their proper perspective).

And, first, we are not to dream of such a presence of Christ in the sacrament as the artificers of the Romish court have imagined, as if the body of Christ, locally present, were to be taken into the hand, and chewed by the teeth, and swallowed by the throat.

As the fathers pretty much unanimously believed: so even Protestant historians freely concede. It has nothing particularly to do with “Romish” and everything to do with apostolic and patristic.

This was the form of Palinode, which Pope Nicholas dictated to Berengarius, in token of his repentance, a form expressed in terms so monstrous, that the author of the Gloss exclaims, that there is danger, if the reader is not particularly cautious, that he will be led by it into a worse heresy than was that of Berengarius (Distinct. 2 c. Ego Berengarius).

Berengarius was one of the few men of any note in the entire patristic and early medieval period who questioned the Real Presence and transubstantiation; hence we see Calvin immediately gravitating to him, even before he engages in his usual pretense that St. Augustine supposedly agrees with his novel position. In the article on Berengarius in the Catholic Encyclopedia, we can see from whence Calvin got some of his heretical notions of the Eucharist:

In the Eucharistic controversy of the ninth century, Radbert Paschasius, afterwards abbot of Corbie, in his De Corpore et Sanguine Domini (831), had maintained the doctrine that in the Holy Eucharist the bread is converted into the real body of Christ, into the very body which was born of Mary and crucified. Ratramnus, a monk of the same abbey, defended the opinion that in the Holy Eucharist there is no conversion of the bread; that the body of Christ is, nevertheless, present, but in a spiritual way; that it is not therefore the same as that born of Mary and crucified. John Scotus Erigena had supported the view that the sacraments of the altar are figures of the body of Christ; that they are a memorial of the true body and blood of Christ. (P. Batiffol, Etudes d’histoire et de théologie positive, 2d series, Paris, 1905.)

Unlike Calvin, who was firm in his error, Berengarius waffled and vacillated, but like Calvin, he went his own way over against Rome:

At the Council of Tours (1055), presided over by the papal legate Hildebrand, Berengarius signed a profession of faith wherein he confessed that after consecration the bread and wine are truly the body and blood of Christ. At another council held in Rome in 1059, Berengarius was present, retracted his opinions, and signed a formula of faith, drawn up by Cardinal Humbert, affirming the real and sensible presence of the true body of Christ in the Holy Eucharist. (Mansi, XIX, 900.) On his return, however, Berengarius attacked this formula. Eusebius Bruno abandoned him, and the Count of Anjou, Geoffrey the Bearded, vigorously opposed him. Berengarius appealed to Pope Alexander II, who, though he intervened in his behalf, asked him to renounce his erroneous opinions. This Berengarius contemptuously refused to do. . . . in 1078, by order of Pope Gregory VII, he came to Rome, and in a council held in St. John Lateran signed a profession of faith affirming the conversion of the bread into the body of Christ, born of the Virgin Mary. The following year, in a council held in the same place Berengarius signed a formula affirming the same doctrine in a more explicit way. Gregory VII then recommended him to the bishops of Tours and Angers, forbidding that any penalty should be inflicted on him or that anyone should call him a heretic. Berengarius, on his return, again attacked the formula he had signed, but as a consequence of the Council of Bordeaux (1080) he made a final retraction. He then retired into solitude on the island of St. Cosme, where he died, in union with the Church.

As the article proceeds in its analysis, we see again the similarities of the false premises of both Berengarius’ and Calvin’s heretical errors: particularly the notion of merely “spiritual presence”:

In order to understand his opinion, we must observe that, in philosophy, Berengarius had rationalistic tendencies and was a nominalist. Even in the study of the question of faith, he held that reason is the best guide. Reason, however, is dependent upon and is limited by sense-perception. Authority, therefore, is not conclusive; we must reason according to the data of our senses. There is no doubt that Berengarius denied transubstantiation (we mean the substantial conversion expressed by the word; the word itself was used for the first time by Hildebert of Lavardin); it is not absolutely certain that he denied the Real Presence, though he certainly held false views regarding it. Is the body of Christ present in the Eucharist, and in what manner? On this question the authorities appealed to by Berengarius are, besides Scotus Erigena, St. Jerome, St. Ambrose, and St. Augustine. These fathers taught that the Sacrament of the Altar is the figure, the sign, the token of the body and blood of the Lord. These terms, in their mind, apply directly to what is external and sensible in the Holy Eucharist and do not, in any way, imply the negation of the real presence of the true body of Christ. (St. Aug. Serm. 143, n.3; Gerbert, Libellus De Corp. et Sang. Domini. n. 4, P.L., CXXXIX, 177.) For Berengarius the body and blood of Christ are really present in the Holy Eucharist; but this presence is an intellectual or spiritual presence. The substance of the bread and the substance of the wine remain unchanged in their nature, but by consecration they become spiritually the very body and blood of Christ. This spiritual body and blood of Christ is the res sacramenti; the bread and the wine are the figure, the sign, the token, sacramentum. . . .

He maintained that the bread and wine, without any change in their nature, become by consecration the sacrament of the body and blood of Christ, a memorial of the body crucified and of the blood shed on the cross. It is not, however, the body of Christ as it is in heaven; for how could the body of Christ which is now in heaven, necessarily limited by space, be in another place, on several altars, and in numerous hosts? Yet the bread and the wine are the sign of the actual and real presence of the body and blood of Christ.

Calvin, too, had pronounced rationalistic and nominalistic tendencies. And so we see some of the intellectual background of his heresies in this regard.

Peter Lombard, though he labours much to excuse the absurdity, rather inclines to a different opinion. As we cannot at all doubt that it is bounded according to the invariable rule in the human body, and is contained in heaven, where it was once received, and will remain till it return to judgment, so we deem it altogether unlawful to bring it back under these corruptible elements, or to imagine it everywhere present.

Jesus’ body is not “everywhere present.” It is sacramentally present in the consecrated bread and wine at Mass. In fact, the very notion of consecration proves that transubstantiation does not involve a “bodily omnipresence” since what was once bread and wine miraculously becomes the Body and Blood of Christ. Therefore, if they were not that before consecration, then this proves that Jesus’ body is not omnipresent itself, but becomes present locally during Mass.

Absurdities abound here, but in Calvin’s view, not the Catholic position. Jesus could walk through walls after His Resurrection (Jn 20:26), and even a mere man, Philip, could be “caught away” and transported to another place by God (Acts 8:39-40). So some Protestants think that God “couldn’t” or “wouldn’t” have performed the miracle of the Eucharist? One shouldn’t attempt to “tie” God’s hands by such arguments of alleged implausibility.

*

And, indeed, there is no need of this, in order to our partaking of it, since the Lord by his Spirit bestows upon us the blessing of being one with him in soul, body, and spirit. The bond of that connection, therefore, is the Spirit of Christ, who unites us to him, and is a kind of channel by which everything that Christ has and is, is derived to us. For if we see that the sun, in sending forth its rays upon the earth, to generate, cherish, and invigorate its offspring, in a manner transfuses its substance into it, why should the radiance of the Spirit be less in conveying to us the communion of his flesh and blood?

Calvin’s scenario is entirely possible, theoretically. The problem is that it denies the clear biblical warrant for eucharistic realism.

Wherefore the Scripture, when it speaks of our participation with Christ, refers its whole efficacy to the Spirit. Instead of many, one passage will suffice. Paul, in the Epistle to the Romans (Rom. 8:9-11), shows that the only way in which Christ dwells in us is by his Spirit. By this, however, he does not take away that communion of flesh and blood of which we now speak, but shows that it is owing to the Spirit alone that we possess Christ wholly, and have him abiding in us.

The indwelling itself is spiritual, and it is said that Jesus dwells inside of us, as well as the Holy Spirit, and indeed God the Father. But the same Scripture uses realistic language in describing the Body of Christ. Calvin himself alluded to this in passing not long before in his book. The clearest, most graphic example of that is in conjunction with St. Paul’s conversion:

Acts 9:3-4 And he fell to the ground and heard a voice saying to him, “Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?” [5] And he said, “Who are you, Lord?” And he said, “I am Jesus, whom you are persecuting;

Acts 22:7-8 And I fell to the ground and heard a voice saying to me, `Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?’ [8] And I answered, `Who are you, Lord?’ And he said to me, `I am Jesus of Nazareth whom you are persecuting.’

Acts 26:14-15 And when we had all fallen to the ground, I heard a voice saying to me in the Hebrew language, `Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me? It hurts you to kick against the goads.’ [15] And I said, `Who are you, Lord?’ And the Lord said, `I am Jesus whom you are persecuting.

Paul wasn’t literally persecuting Jesus in the flesh. He was warring against the Body of Christ. Jesus assumes here that the “Body of Christ” or the Church is literally identified with Him, in some very real sense. It’s the typically pungent, literal, graphic language and categories of the Bible. Paul was persecuting the Church:

Acts 9:1-2 But Saul, still breathing threats and murder against the disciples of the Lord, went to the high priest [2] and asked him for letters to the synagogues at Damascus, so that if he found any belonging to the Way, men or women, he might bring them bound to Jerusalem.

Acts 22:4-5 I persecuted this Way to the death, binding and delivering to prison both men and women, [5] as the high priest and the whole council of elders bear me witness. From them I received letters to the brethren, and I journeyed to Damascus to take those also who were there and bring them in bonds to Jerusalem to be punished.

Acts 26:10-11 I not only shut up many of the saints in prison, by authority from the chief priests, but when they were put to death I cast my vote against them. [11] And I punished them often in all the synagogues and tried to make them blaspheme; and in raging fury against them, I persecuted them even to foreign cities.

1 Corinthians 15:9 For I am the least of the apostles, unfit to be called an apostle, because I persecuted the church of God.

Galatians 1:23 For you have heard of my former life in Judaism, how I persecuted the church of God violently and tried to destroy it; (cf. 1:23)

But Jesus told him that he was persecuting Him. This graphic one-to-one equation is seen elsewhere:

Ephesians 1:22-23 and he has put all things under his feet and has made him the head over all things for the church, [23] which is his body, the fulness of him who fills all in all.

Ephesians 5:23 . . . Christ is the head of the church, his body, and is himself its Savior.

Ephesians 5:28-32 Even so husbands should love their wives as their own bodies. He who loves his wife loves himself. [29] For no man ever hates his own flesh, but nourishes and cherishes it, as Christ does the church, [30] because we are members of his body. [31] “For this reason a man shall leave his father and mother and be joined to his wife, and the two shall become one flesh.” [32] This mystery is a profound one, and I am saying that it refers to Christ and the church;

Paul also reiterates the equation of persecution of the Church being the same as persecuting Jesus Himself:

1 Timothy 1:12-13 I thank him who has given me strength for this, Christ Jesus our Lord, because he judged me faithful by appointing me to his service, [13] though I formerly blasphemed and persecuted and insulted him; but I received mercy because I had acted ignorantly in unbelief,

Elsewhere we see in the Apostle Paul not only very strong eucharistic realism (1 Cor 10:16; 11:27-30) but also an identification with the very suffering of Christ, in a startlingly realistic manner:

Colossians 1:24 Now I rejoice in my sufferings for your sake, and in my flesh I complete what is lacking in Christ’s afflictions for the sake of his body, that is, the church, (cf. 2 Cor 4:10; Gal 6:17; Phil 3:10)

Calvin can’t spiritualize away Paul’s bodily sufferings, as if they weren’t physical in nature. Likewise, he can’t spiritualize away the Holy Eucharist. Scripture is consistently realistic in tone, tenor, and language with regard to all these matters.

*

The Schoolmen, horrified at this barbarous impiety,

What impiety?

speak more modestly, though they do nothing more than amuse themselves with more subtle delusions.

Quite an underhanded compliment . . .

They admit that Christ is not contained in the sacrament circumscriptively, or in a bodily manner, but they afterwards devise a method which they themselves do not understand, and cannot explain to others.

Sounds rather like Calvin’s own discombobulated eucharistic theology.

It, however, comes to this, that Christ may be sought in what they call the species of bread. What? When they say that the substance of bread is converted into Christ, do they not attach him to the white colour, which is all they leave of it? But they say, that though contained in the sacrament, he still remains in heaven, and has no other presence there than that of abode.

On what grounds can Calvin or his followers argue that this is impossible? I don’t see at all that it is impossible for God or prohibited by the Bible. Colossians 3:11 states that “Christ is all, and in all.” The Bible refers to God being “in” physical things, such as fire and clouds (so why not also under the appearances of bread and wine?). Exodus 33:9-10 even informs us that the ancient Israelites would worship God in the pillar of cloud and 2 Chronicles 7:3 states that they “bowed down with their faces to the earth on the pavement, and worshiped” before God in both the fire and the cloud. Moses and Aaron “fell on their faces” before the Shekinah glory cloud (Num 20:6). All of this is exactly analogous to eucharistic adoration of the host:

GOD IN FIRE*Exodus 3:2-6 And the angel of the LORD appeared to him in a flame of fire out of the midst of a bush; and he looked, and lo, the bush was burning, yet it was not consumed. [3] And Moses said, “I will turn aside and see this great sight, why the bush is not burnt.” [4] When the LORD saw that he turned aside to see, God called to him out of the bush, “Moses, Moses!” And he said, “Here am I.” [5] Then he said, “Do not come near; put off your shoes from your feet, for the place on which you are standing is holy ground.” [6] And he said, “I am the God of your father, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob.” And Moses hid his face, for he was afraid to look at God. (cf. Acts 7:30-33; Dt. 4:12, 15; 5:4-5; Mk 12:26; Lk 20:37)

Exodus 13:21 And the LORD went before them . . . by night in a pillar of fire to give them light, that they might travel by day and by night; (cf. 14:24)

Exodus 19:18 And Mount Sinai was wrapped in smoke, because the LORD descended upon it in fire; and the smoke of it went up like the smoke of a kiln, and the whole mountain quaked greatly. (cf. 24:17)

Exodus 40:38 For throughout all their journeys the cloud of the LORD was upon the tabernacle by day, and fire was in it by night, in the sight of all the house of Israel. (cf. Num 14:14; Dt 1:32-33; Neh 9:12, 19)

Deuteronomy 4:12 Then the LORD spoke to you out of the midst of the fire; you heard the sound of words, but saw no form; there was only a voice. (cf. 4:15)

Deuteronomy 5:22 These words the LORD spoke to all your assembly at the mountain out of the midst of the fire, . . . (cf. 9:10; 10:4)

GOD IN THE SHEKINAH CLOUD / “GLORY OF THE LORD”*Exodus 13:21 And the LORD went before them by day in a pillar of cloud to lead them along the way, . . . (cf. 14:24; 16:10; Dt 1:33; 31:15)

Exodus 24:15-16 Then Moses went up on the mountain, and the cloud covered the mountain. [16] The glory of the LORD settled on Mount Sinai, and the cloud covered it six days; and on the seventh day he called to Moses out of the midst of the cloud.

Exodus 33:9-11 When Moses entered the tent, the pillar of cloud would descend and stand at the door of the tent, and the LORD would speak with Moses. [10] And when all the people saw the pillar of cloud standing at the door of the tent, all the people would rise up and worship, every man at his tent door. [11] Thus the LORD used to speak to Moses face to face, as a man speaks to his friend. When Moses turned again into the camp, his servant Joshua the son of Nun, a young man, did not depart from the tent. . . . [14] And he said, “My presence will go with you, and I will give you rest.” (cf. Num 14:10, 14; 16:19, 42)

Exodus 34:5 And the LORD descended in the cloud and stood with him there, and proclaimed the name of the LORD.

Exodus 40:34-38 Then the cloud covered the tent of meeting, and the glory of the LORD filled the tabernacle. [35] And Moses was not able to enter the tent of meeting, because the cloud abode upon it, and the glory of the LORD filled the tabernacle. [36] Throughout all their journeys, whenever the cloud was taken up from over the tabernacle, the people of Israel would go onward; [37] but if the cloud was not taken up, then they did not go onward till the day that it was taken up. [38] For throughout all their journeys the cloud of the LORD was upon the tabernacle by day, . . . (cf. Lev 9:4-6, 23)

Leviticus 16:2 and the LORD said to Moses, . . . “I will appear in the cloud upon the mercy seat.” [ark of the covenant]

Numbers 11:25 Then the LORD came down in the cloud and spoke to him . . .

Numbers 20:6-7 Then Moses and Aaron went from the presence of the assembly to the door of the tent of meeting, and fell on their faces. And the glory of the LORD appeared to them, [7] and the LORD said to Moses,

Deuteronomy 5:22 These words the LORD spoke to all your assembly at the mountain out of the midst of . . . the cloud, and the thick darkness, with a loud voice . . .

1 Kings 8:11 so that the priests could not stand to minister because of the cloud; for the glory of the LORD filled the house of the LORD. (cf. 2 Chr 5:14)

2 Chronicles 7:1-3 When Solomon had ended his prayer, fire came down from heaven and consumed the burnt offering and the sacrifices, and the glory of the LORD filled the temple. [2] And the priests could not enter the house of the LORD, because the glory of the LORD filled the LORD’s house. [3] When all the children of Israel saw the fire come down and the glory of the LORD upon the temple, they bowed down with their faces to the earth on the pavement, and worshiped and gave thanks to the LORD, saying, “For he is good, for his steadfast love endures for ever.”

Psalm 99:7 He spoke to them in the pillar of cloud . . . (cf. Neh 9:12,19)

Ezekiel 10:4, 18 And the glory of the LORD went up from the cherubim to the threshold of the house; and the house was filled with the cloud, and the court was full of the brightness of the glory of the LORD. . . . Then the glory of the LORD went forth from the threshold of the house, and stood over the cherubim.

Yet Calvin would have us believe that it is implausible or unbiblical or impossible that God (after the Incarnation) could choose to be physically present in the consecrated elements? He simply cannot do so. It is a mere false tradition of men that would dogmatically assert such a thing without biblical justification. As I’ve just shown, the Bible has many indications of a local presence of God in physical things, even apart from the Incarnation.

Eucharistic presence is scarcely any essentially different than all these manifestations of His special presence. God was so present in the ark of the covenant, that Uzzah was killed instantly simply because he innocently touched it, to keep it from falling over (2 Sam 6:3-7; 1 Chr 13:7-10). Seventy men of Bethshemesh were slain because they (also seemingly innocently) looked into it (1 Sam 6:19).

*

Joshua even bowed before the ark of the covenant on his face in a worshipful posture (Josh 7:6), and Levite priests thanked and praised God before it (1 Chr 16:4), just as Catholics genuflect and bow before the Holy Eucharist, and adore the Lord therein. King David “offered burnt offerings and peace offerings before the LORD” next to the ark (2 Sam 6:17), which is a precursor of the Sacrifice of the Mass. King Solomon did the same (1 Kgs 3:15; 2 Chr 5:6), and so did the Levites (1 Chr 16:1). Catholic practices are essentially nothing that hadn’t been done nearly 3000 years ago. They are made far more meaningful, however, after the incarnation and crucifixion and resurrection of our Lord Jesus Christ.

But, whatever be the terms in which they attempt to make a gloss, the sum of all is, that that which was formerly bread, by consecration becomes Christ: so that Christ thereafter lies hid under the colour of bread.

That’s correct; as the fathers taught.

This they are not ashamed distinctly to express.

Why should we be, since Jesus and Paul did?

For Lombard’s words are, “The body of Christ, which is visible in itself, lurks and lies covered after the act of consecration under the species of bread” (Lombard. Sent. Lib. 4 Dist. 12). Thus the figure of the bread is nothing but a mask which conceals the view of the flesh from our eye. But there is no need of many conjectures to detect the snare which they intended to lay by these words, since the thing itself speaks clearly. It is easy to see how great is the superstition under which not only the vulgar but the leaders also, have laboured for many ages, and still labour, in Popish Churches.

If Calvin wishes to condemn the entirety of patristic eucharistic theology (and the explicit biblical rationale behind it), he is free to do so, but this also means that he can’t pretend to be “reforming” the Church back to her former state in this regard, since there never was a time when the Church believed as he does regarding the Eucharist. He can’t have his cake and eat it too (no pun intended).

*

Little solicitous as to true faith (by which alone we attain to the fellowship of Christ, and become one with him), provided they have his carnal presence, which they have fabricated without authority from the word, they think he is sufficiently present. Hence we see, that all which they have gained by their ingenious subtlety is to make bread to be regarded as God.

Calvin does the latter, as I alluded to above, since he makes the bread remain bread, yet wants to talk as if God is specially, mystically, spiritually present in it. So if anyone is confusing bread and God, it is Calvin. He is mixing the two in an odd, illogical manner. Lutherans, on the other hand, make it clear that both bread and God are present, and distinguish the two, while Catholics explicitly hold to a change in substance from bread to God.

Luke 22:19-20 (RCV) And he took bread, and when he had given thanks he broke it and gave it to them, saying, “This is represents my body which is given for you, as a sign and seal. Do this in remembrance of me.” [20] And likewise the cup after supper, saying, “This cup which is poured out for you represents the new covenant in my blood, as a sign and seal.”

1 Corinthians 10:16 (RCV) The cup of blessing which we bless, does it not represent and signify in a spiritual manner the blood of Christ, that we mystically participate in? The bread which we break, does it not represent and signify in a spiritual manner the body of Christ, that we mystically participate in?

1 Corinthians 11:27-29 (RCV) Whoever, therefore, eats the bread or drinks the cup of the Lord in an unworthy manner will be guilty of profaning what represents and signifies as a spiritual sign the body and blood of the Lord. [28] Let a man examine himself, and so eat of the bread and drink of the cup. [29] For any one who eats and drinks without discerning what represents and signifies as a spiritual sign the body eats and drinks judgment upon himself.

Well, no; transubstantiation means literally, “change of substance,” so the view is that the substance changes from bread to the Body and Blood of Christ, not that it changes to “nothing.” This makes perfect sense, since Jesus said “this is My body” and referred to eating His flesh and drinking His blood in John 6. Calvin simply lacks faith that God can do this miracles. He wants to limit God and place His actions in arbitrary categories of his own making: certainly not from scriptural indications.

It is strange that they have fallen into such a degree of ignorance, nay, of stupor, as to produce this monstrous fiction not only against Scripture, but also against the consent of the ancient Church. I admit, indeed, that some of the ancients occasionally used the term conversion, not that they meant to do away with the substance in the external signs, but to teach that the bread devoted to the sacrament was widely different from ordinary bread, and was now something else.

What else does “conversion” or “transformation” or “change” mean? This is just more word games from Calvin. He thinks that if he wishes long enough, that the fathers will magically agree with him, when in fact they do not at all. Calvin would have it that the consent of the ancient Church is on his side, with regard to this question. Nothing could be further from the truth. It’s wearisome to have to repeatedly point out historical facts over against Calvin. But I’m happy to set the record straight and reveal once again the surprisingly great weakness of Calvin’s historical arguments (as well as biblical ones).

All clearly and uniformly teach that the sacred Supper consists of two parts, an earthly and a heavenly. The earthly they without dispute interpret to be bread and wine. Certainly, whatever they may pretend, it is plain that antiquity, which they often dare to oppose to the clear word of God, gives no countenance to that dogma. It is not so long since it was devised; indeed, it was unknown not only to the better ages, in which a purer doctrine still flourished, but after that purity was considerably impaired. There is no early Christian writer who does not admit in distinct terms that the sacred symbols of the Supper are bread and wine, although, as has been said, they sometimes distinguish them by various epithets, in order to recommend the dignity of the mystery.

This is sheer nonsense, and one can prove it by citing prominent Protestant historians of Christian doctrine. For example:

In general, this period, . . . was already very strongly inclined toward the doctrine of transubstantiation, and toward the Greek and Roman sacrifice of the mass, which are inseparable in so far as a real sacrifice requires the real presence of the victim…… (Philip Schaff, History of the Christian Church, vol. 3, A. D. 311-600, revised 5th edition, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans, reprinted 1974, originally 1910, p. 500)

Theodore [c.350-428] set forth the doctrine of the real presence, and even a theory of sacramental transformation of the elements, in highly explicit language . . . ‘At first it is laid upon the altar as a mere bread and wine mixed with water, but by the coming of the Holy Spirit it is transformed into body and blood, and thus it is changed into the power of a spiritual and immortal nourishment.’ [Hom. catech. 16,36] these and similar passages in Theodore are an indication that the twin ideas of the transformation of the eucharistic elements and the transformation of the communicant were so widely held and so firmly established in the thought and language of the church that everyone had to acknowledge them. (Jaroslav Pelikan, The Emergence of the Catholic Tradition (100-600), Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1971, 236-237)

Since Calvin insists that the fathers agree with him, I will now document that they do not; that transubstantiation in kernel form (not yet fully developed, as in the case of all complex doctrines, such as the Holy Trinity and Christology, that develop over many centuries) was indeed taught by many fathers, just as historian Philip Schaff (no fan of the doctrine at all) verified:

St. Irenaeus

When, therefore, the mingled cup and the manufactured bread receives the Word of God, and the Eucharist of the blood and the body of Christ is made, from which things the substance of our flesh is increased and supported, how can they affirm that the flesh is incapable of receiving the gift of God, which is life eternal, which [flesh] is nourished from the body and blood of the Lord, and is a member of Him?—even as the blessed Paul declares in his Epistle to the Ephesians, that “we are members of His body, of His flesh, and of His bones.” He does not speak these words of some spiritual and invisible man, for a spirit has not bones nor flesh; but [he refers to] that dispensation [by which the Lord became] an actual man, consisting of flesh, and nerves, and bones,—that [flesh] which is nourished by the cup which is His blood, and receives increase from the bread which is His body. (Against Heresies, V, 2, 3; ANF, Vol. I)

Origen

You are accustomed to take part in the divine mysteries, so you know how, when you have received the Body of the Lord, you reverently exercise care lest a particle fall, and lest anything of the consecrated gift perish. . . . But if you observe such caution in keeping His Body, and properly so, how is it that you think neglecting the word of God a lesser crime than neglecting His Body? (Homilies on Exodus, 13, 3)

St. Cyprian

And therefore we ask that our bread—that is, Christ—may be given to us daily, that we who abide and live in Christ may not depart from His sanctification and body. (On the Lord’s Prayer / Treatise IV, 18; ANF, Vol. V)

St. Athanasius

You will see the Levites bringing loaves and a cup of wine, and placing them on the table. So long as the prayers and invocations have not yet been made, it is mere bread and a mere cup. But when the great and wondrous prayers have been recited, then the bread becomes the body and the cup the blood of our Lord Jesus Christ. . . . When the great prayers and holy supplications are sent up, the Word descends on the bread and the cup, and it becomes His body. (Sermon to the Newly-Baptized)

St. Cyril of Jerusalem

For as the Bread and Wine of the Eucharist before the invocation of the Holy and Adorable Trinity were simple bread and wine, while after the invocation the Bread becomes the Body of Christ, and the Wine the Blood of Christ . . . (Catechetical Lecture XIX, 7; NPNF 2, Vol. VII)

Even of itself the teaching of the Blessed Paul is sufficient to give you a full assurance concerning those Divine Mysteries, of which having been deemed worthy, ye are become of the same body and blood with Christ . . . Since then He Himself declared and said of the Bread, This is My Body, who shall dare to doubt any longer? And since He has Himself affirmed and said, This is My Blood, who shall ever hesitate, saying, that it is not His blood? (Catechetical Lecture XXII, 1; NPNF 2, Vol. VII)

Wherefore with full assurance let us partake as of the Body and Blood of Christ: for in the figure of Bread is given to thee His Body, and in the figure of Wine His Blood; that thou by partaking of the Body and Blood of Christ, mayest be made of the same body and the same blood with Him. For thus we come to bear Christ in us, because His Body and Blood are distributed through our members; thus it is that, according to the blessed Peter, we become partakers of the divine nature. (Catechetical Lecture XXII, 3; NPNF 2, Vol. VII)

Consider therefore the Bread and the Wine not as bare elements, for they are, according to the Lord’s declaration, the Body and Blood of Christ; for even though sense suggests this to thee, yet let faith establish thee. Judge not the matter from the taste, but from faith be fully assured without misgiving, that the Body and Blood of Christ have been vouchsafed to thee. (Catechetical Lecture XXII, 6; NPNF 2, Vol. VII)

Having learnt these things, and been fully assured that the seeming bread is not bread, though sensible to taste, but the Body of Christ; and that the seeming wine is not wine, though the taste will have it so, but the Blood of Christ . . . (Catechetical Lecture XXII, 9; NPNF 2, Vol. VII)

Then having sanctified ourselves by these spiritual Hymns, we beseech the merciful God to send forth His Holy Spirit upon the gifts lying before Him; that He may make the Bread the Body of Christ, and the Wine the Blood of Christ; for whatsoever the Holy Ghost has touched, is surely sanctified and changed.

Then, after the spiritual sacrifice, the bloodless service, is completed, over that sacrifice of propitiation we entreat God for the common peace of the Churches, for the welfare of the world; for kings; for soldiers and allies; for the sick; for the afflicted; and, in a word, for all who stand in need of succour we all pray and offer this sacrifice. (Catechetical Lecture XXIII, 7-8; NPNF 2, Vol. VII)

St. Gregory of Nyssa

Rightly, then, do we believe that now also the bread which is consecrated by the Word of God is changed into the Body of God the Word. (The Great Catechism, chapter XXXVII; NPNF 2, Vol. IV)

The footnote in NPNF 2 for this passage states:

by the process of eating . . . If Krabinger’s text is here correct, Gregory distinctly teaches a transmutation of the elements very like the later transubstantiation: he also distinctly teaches that the words of consecration effect the change. There seems no reason to doubt that the text is correct.

St. Ambrose

. . . We observe, then, that grace has more power than nature, and yet so far we have only spoken of the grace of a prophet’s blessing. But if the blessing of man had such power as to change nature, what are we to say of that divine consecration where the very words of the Lord and Saviour operate? For that sacrament which you receive is made what it is by the word of Christ. But if the word of Elijah had such power as to bring down fire from heaven, shall not the word of Christ have power to change the nature of the elements? You read concerning the making of the whole world: “He spake and they were made, He commanded and they were created.” Shall not the word of Christ, which was able to make out of nothing that which was not, be able to change things which already are into what they were not? For it is not less to give a new nature to things than to change them.

But why make use of arguments? Let us use the examples He gives, and by the example of the Incarnation prove the truth of the mystery. Did the course of nature proceed as usual when the Lord Jesus was born of Mary? If we look to the usual course, a woman ordinarily conceives after connection with a man. And this body which we make is that which was born of the Virgin. Why do you seek the order of nature in the Body of Christ, seeing that the Lord Jesus Himself was born of a Virgin, not according to nature? It is the true Flesh of Christ which crucified and buried, this is then truly the Sacrament of His Body.

The Lord Jesus Himself proclaims: “This is My Body.” Before the blessing of the heavenly words another nature is spoken of, after the consecration the Body is signified. He Himself speaks of His Blood. Before the consecration it has another name, after it is called Blood. (On the Mysteries, Chapter IX, 50, 52-55; NPNF 2, Vol. X)

St. John Chrysostom

Christ is present. The One who prepared that [Holy Thursday] table is the very One who now prepares this [altar] table. For it is not a man who makes the sacrificial gifts become the Body and Blood of Christ, but He that was crucified for us, Christ Himself. The priest stands there carrying out the action, but the power and grace is of God. “This is My Body,” he says. This statement transforms the gifts. (Homilies on the Treachery of Judas, 1, 6)

St. Augustine

For not all bread, but only that which receives the blessing of Christ, becomes Christ’s body. (Sermons, 234, 2)

St. Cyril of Alexandria

He states demonstratively: “This is My Body,” and “This is My Blood“(Mt. 26:26-28) “lest you might suppose the things that are seen as a figure. Rather, by some secret of the all-powerful God the things seen are transformed into the Body and Blood of Christ, truly offered in a sacrifice in which we, as participants, receive the life-giving and sanctifying power of Christ. (Commentary on Matthew [Mt. 26:27] )

Moreover, the belief of these same Church fathers, en masse, in the Sacrifice of the Mass, and the adoration of the Body and Blood after consecration, attests to their realism, over against Calvin’s mere mystical symbolism. We shall examine that aspect in the near future, in reply to Calvin’s (absurd, anti-historical, anti-patristic) thoughts on the Mass.

For when they say that a secret conversion takes place at consecration, so that it is now something else than bread and wine, their meaning, as I already observed, is, not that these are annihilated, but that they are to be considered in a different light from common food, which is only intended to feed the body, whereas in the former the spiritual food and drink of the mind are exhibited. This we deny not. But, say our opponents, if there is conversion, one thing must become another. If they mean that something becomes different from what it was before, I assent. If they will wrest it in support of their fiction, let them tell me of what kind of change they are sensible in baptism. For here, also, the Fathers make out a wonderful conversion, when they say that out of the corruptible element is made the spiritual laver of the soul, and yet no one denies that it still remains water.

This is true, but it is an invalid analogy, because no one is claiming in baptism that waters becomes something else: only that it acquires supernatural powers in conjunction with a baptismal formula. Jesus never said that baptismal water would become His Body and Blood, whereas He did say that with regard to what were formerly bread and wine. It’s an entirely different scenario, so there is no analogy. The information we have in Scripture regarding both cases is entirely different in kind.

But say they, there is no such expression in Baptism as that in the Supper, This is my body; as if we were treating of these words, which have a meaning sufficiently clear, and not rather of that term conversion, which ought not to mean more in the Supper than in Baptism. Have done, then, with those quibbles upon words, which betray nothing but their silliness.

It’s not silly at all (but it is sophistry and desperate obfuscation to conclude that an obviously relevant point is “silliness”). Catholics are accepting at face value the actual words of Scripture and our Lord. Calvin is not. It’s really as simple and obvious as that. Calvin doesn’t have enough faith to believe our Lord’s words as He spoke them. He would rather hyper-analyze them and apply men’s traditions and non-biblical philosophies, so that he can change their meaning. We believe in faith that the bread and wine are transformed, but Calvin, lacking faith, believes in transforming the clear import and meaning of Jesus’ words: reading into them what clearly isn’t there.

The meaning would have no congruity, unless the truth which is there figured had a living image in the external sign. Christ wished to testify by an external symbol that his flesh was food.

That’s not what He said! That is Calvin eisegetically reading into what He said. Jesus said “this is my body” not “this represents my Body as a sign and symbol.” St. Paul casually assumed the same eucharistic realism, and even said that those approaching the Eucharist unworthily were guilty of profaning Jesus’ Body and Blood (1 Cor 11:27-30): something that makes no sense whatever if only symbols are present.

If he exhibited merely an empty show of bread, and not true bread, where is the analogy or similitude to conduct us from the visible thing to the invisible? For, in order to make all things consistent, the meaning cannot extend to more than this, that we are fed by the species of Christ’s flesh; just as, in the case of baptism, if the figure of water deceived the eye, it would not be to us a sure pledge of our ablution; nay, the fallacious spectacle would rather throw us into doubt. The nature of the sacrament is therefore overthrown, if in the mode of signifying the earthly sign corresponds not to the heavenly reality; and, accordingly, the truth of the mystery is lost if true bread does not represent the true body of Christ.

No; Calvin just doesn’t go deep enough in his understanding. In the Holy Eucharist Jesus gives us Himself, not just signs and figures of Himself. That is the beauty and profundity of it. It extends the incarnation, just as the various extraordinary manifestations of God’s spiritual presence extended the notion of omnipresence. When God was known as a spirit only, He was specially present spiritually and immaterially, yet directly connected with physical objects, as in the ark of the covenant, or fire, or clouds.

Even then He manifested Himself physically on occasion (as in theophanies). Now, after the incarnation and Sacrifice of the Lamb, and the resurrection, He makes Himself present physically as well, in a miraculous way. Why this should be scandalous to anyone is a bigger mystery than transubstantiation itself. Jesus is our paschal lamb. The lamb was eaten at every Passover. If Calvin wants to talk analogies, the Eucharist shouldn’t be compared to baptism, but to the Passover meal, which is what the Last Supper was.

I again repeat, since the Supper is nothing but a conspicuous attestation to the promise which is contained in the sixth chapter of John—viz. that Christ is the bread of life, who came down from heaven, that visible bread must intervene, in order that that spiritual bread may be figured, unless we would destroy all the benefits with which God here favours us for the purpose of sustaining our infirmity. Then on what ground could Paul infer that we are all one bread, and one body in partaking together of that one bread, if only the semblance of bread, and not the natural reality, remained?

He does so on the grounds that we really receive Jesus. He becomes part of us and we become part of Him, in the eucharistic mystery and miracle, and in line with 2 Peter 1:3-4 and the biblical notion of theosis, or divinization. We are the Body of Christ, which is equated with Jesus own body in a large sense. We don’t deny that there is also a figure of bread and wine involved (just as St. Augustine taught), and Paul still uses that language. But he means it quite literally, whereas Calvin spiritualizes everything away. We don’t deny the symbolism, but Calvin denies the reality. He is (as usual) “either/or”; we are “both/and.”

*

“Magic” is something that Calvin has derisively superimposed onto Catholic doctrine. It is not magic by men’s will and power, but mystery and miracle by God’s will and power. He is the one who set up Holy Communion, at the Last Supper, and in the John 6 discourse. All we’re doing is being obedient, in doing what He commanded us to do, and eating His Body and Blood, as He said we should do in order to be saved (John 6). Calvin is foolish enough to apply to Catholics what the pagan Romans applied to all Christians: a notion that Holy Communion was a crude cannibalism. He’d rather think like a pagan than like apostolic Christians (like St. Paul).

They overlooked the principle, that bread is a sacrament to none but those to whom the word is addressed, just as the water of baptism is not changed in itself, but begins to be to us what it formerly was not, as soon as the promise is annexed.

Baptism exercises its power due to faith and the trinitarian baptismal formula pronounced over it. Likewise, transubstantiation occurs when the priest, exercising faith with the congregants, pronounces for formula of consecration over the bread and wine. Change occurs in both instances, though in a different fashion: baptism causes a regeneration in the baptized (which Calvin denies). The words of consecration cause transubstantiation, and the bread and wine become the Body and Blood (which Calvin denies), just as they did at the Last Supper. Calvin compares the wrong things to each other, and so misses the common elements between both sacraments. Matter conveys grace in both instances.

This will better appear from the example of a similar sacrament. The water gushing from the rock in the desert was to the Israelites a badge and sign of the same thing that is figured to us in the Supper by wine.

Where does Scripture say that? Nowhere, of course . . .

For Paul declares that they drank the same spiritual drink (1 Cor. 10:4). But the water was common to the herds and flocks of the people. Hence it is easy to infer, that in the earthly elements, when employed for a spiritual use, no other conversion takes place than in respect of men, inasmuch as they are to them seals of promises.

Again, this ignores the very words of Christ, which are conclusive in determining the very nature of the sacrament. Calvin makes an improper analogy once again, presumably in desperation, since he keeps skirting around the central issue of Jesus’ own words.

Moreover, since it is the purpose of God, as I have repeatedly inculcated, to raise us up to himself by fit vehicles, those who indeed call us to Christ, but to Christ lurking invisibly under bread, impiously, by their perverseness, defeat this object. For it is impossible for the mind of man to disentangle itself from the immensity of space, and ascend to Christ even above the heavens.

Yes, of course, it is impossible for us under our own power, but that is again beside the point: it is God Who chooses to descend and condescend to us in the Holy Eucharist. Calvin’s “anti-eucharistic realism” arguments are becoming increasingly irrelevant and desperate.

What nature denied them, they attempted to gain by a noxious remedy.

One proposed by Jesus Christ and verified by St. Paul . . . if that is “noxious,” may we all be filled with it! I’d rather be “noxious” in faith than obnoxious out of lack of faith and pagan-derived skepticism.

Remaining on the earth, they felt no need of a celestial proximity to Christ. Such was the necessity which impelled them to transfigure the body of Christ. In the age of Bernard, though a harsher mode of speech had prevailed, transubstantiation was not yet recognised. And in all previous ages, the similitude in the mouths of all was, that a spiritual reality was conjoined with bread and wine in this sacrament.

The patristic evidence presented above amply refutes this characterization.

As to the terms, they think they answer acutely, though they adduce nothing relevant to the case in hand. The rod of Moses (they say), when turned into a serpent, though it acquires the name of a serpent, still retains its former name, and is called a rod; and thus, according to them, it is equally probable that though the bread passes into a new substance, it is still called by catachresis, and not inaptly, what it still appears to the eye to be. But what resemblance, real or apparent, do they find between an illustrious miracle and their fictitious illusion, of which no eye on the earth is witness? The magi by their impostures had persuaded the Egyptians, that they had a divine power above the ordinary course of nature to change created beings. Moses comes forth, and after exposing their fallacies, shows that the invincible power of God is on his side, since his rod swallows up all the other rods. But as that conversion was visible to the eye, we have already observed, that it has no reference to the case in hand. Shortly after the rod visibly resumed its form.

Here Calvin seems to imply that what is not visible to the eye is therefore questionable and unworthy of belief due to that factor alone. And that betrays his undue skepticism and lack of faith in the miracles of God. I wrote in my Jan/Feb 2000 cover story in Envoy Magazine about the Eucharist, in opposing Zwingli’s symbolism, which is not far from Calvin’s view:

The Eucharist was intended by God as a different kind of miracle from the outset, requiring more profound faith, as opposed to the “proof” of tangible, empirical miracles. But in this it was certainly not unique among Christian doctrines and traditional beliefs – many fully shared by our Protestant brethren. The Virgin Birth, for example, cannot be observed or proven, and is the utter opposite of a demonstrable miracle, yet it is indeed a miracle of the most extraordinary sort. Likewise, in the Atonement of Jesus the world sees a wretch of a beaten and tortured man being put to death on a cross. The Christian, on the other hand, sees there the great miracle of Redemption and the means of the salvation of mankind – an unspeakably sublime miracle, yet who but those with the eyes of faith can see or believe it? In fact, the disciples (with the possible exception of St. John, the only one present) didn’t even know what was happening at the time.

Baptism, according to most Christians, imparts real grace of some sort to those who receive it. But this is rarely evident or tangible, especially in infants. Lastly, the Incarnation itself was not able to be perceived as an outward miracle, though it might be considered the most incredible miracle ever. Jesus appeared as a man like any other man. He ate, drank, slept, had to wash, experienced emotion, suffered, etc. He performed miracles and foretold the future, and ultimately raised Himself from the dead, and ascended into heaven in full view, but the Incarnation – strictly viewed in and of itself -, was not visible or manifest in the tangible, concrete way to which Herr Zwingli seems to foolishly think God would or must restrict Himself.

To summarize, Jesus looked, felt, and sounded like a man; no one but those possessing faith would know (from simply observing Him) that He was also God, an uncreated Person who had made everything upon which He stood, who was the Sovereign and Judge of every man with whom He came in contact (and also of those He never met). Therefore, Zwingli’s argument proves too much and must be rejected. If the Eucharist is abolished by this supposed “biblical reasoning,” then the Incarnation (and by implication, the Trinity) must be discarded along with it. . . .

The fact remains that God clearly can perform any miracle He so chooses. Many Christian beliefs require a great deal of faith, even relatively “blind” faith. Protestants manage to believe in a number of such doctrines (such as the Trinity, God’s eternal existence, omnipotence, angels, the power of prayer, instantaneous justification, the Second Coming, etc.). Why should the Real Presence be singled out for excessive skepticism and unchecked rationalism? I contend that it is due to a preconceived bias against both sacramentalism and matter as a conveyor of grace, which hearkens back to the heresies of Docetism and even Gnosticism, which looked down upon matter, and regarded spirit as inherently superior to matter (following Greek philosophy, particularly Platonism).

It may be added, that we know not whether this was an extemporary conversion of substance. For we must attend to the illusion to the rods of the magicians, which the prophet did not choose to term serpents, lest he might seem to insinuate a conversion which had no existence, because those impostors had done nothing more than blind the eyes of the spectators. But what resemblance is there between that expression and the following? “The bread which we break;”—“As often as ye eat this bread;”—“They communicated in the breaking of bread;” and so forth.

That was phenomenological language; in other words, referring to what looked outwardly like bread. In the same context that Paul said these things, he also described the Eucharist as “a participation in the Body of Christ” (1 Cor 10:16) and said that “Whoever, therefore, eats the bread or drinks the cup of the Lord in an unworthy manner will be guilty of profaning the body and blood of the Lord” (1 Cor 11:27).

It is certain that the eye only was deceived by the incantation of the magicians. The matter is more doubtful with regard to Moses, by whose hand it was not more difficult for God to make a serpent out of a rod, and again to make a rod out of a serpent, than to clothe angels with corporeal bodies, and a little after unclothe them. If the case of the sacrament were at all akin to this, there might be some colour for their explanation.

I don’t make this argument myself, and don’t know how prominent it was. Calvin is not known for fair presentation of opposing views, so we can’t tell for sure how widespread such an argument was.

Let it, therefore, remain fixed that there is no true and fit promise in the Supper, that the flesh of Christ is truly meat, unless there is a correspondence in the true substance of the external symbol.

And where is such a thing ever stated in Scripture, or even implied?

But as one error gives rise to another, a passage in Jeremiah has been so absurdly wrested, to prove transubstantiation, that it is painful to refer to it. The prophet complains that wood was placed in his bread, intimating that by the cruelty of his enemies his bread was infected with bitterness, as David by a similar figure complains, “They gave me also gall for my meat: and in my thirst they gave me vinegar to drink” (Psalm 69:21). These men would allegorise the expression to mean, that the body of Christ was nailed to the wood of the cross. But some of the Fathers thought so! As if we ought not rather to pardon their ignorance and bury the disgrace, than to add impudence, and bring them into hostile conflict with the genuine meaning of the prophet.

Nor have I ever made this argument myself, and I don’t know how prominent it was, either, so I’ll pass over it. I’m much more interested in Calvin’s positive arguments for his view, not his mocking of opposing views that were made by who knows how many people. I’ve brought plenty of Bible to the table in my own defense of Catholic views: most of which seem to be unknown or ignored by Calvin.

(originally 24-25 November 2009)

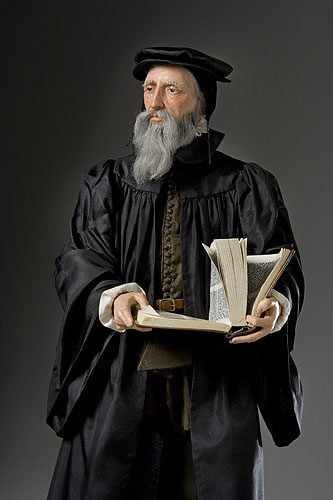

Photo credit: Historical mixed media figure of John Calvin produced by artist/historian George S. Stuart and photographed by Peter d’Aprix: from the George S. Stuart Gallery of Historical Figures archive [Wikimedia Commons / Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license]

***