This is a follow-up discussion: brought about by an atheist’s response to my article, “Atheist vs. Christian Ignorance of the Bible: A Brief Observation.” The words of gusbovona will be in blue. See also our exchange immediately before this one: “Dialogue w Atheist on Biblical Exegesis & Christian Ignorance.”

*****

I’m not sure why you don’t like atheists thinking they are more rational or scientific than Christians. It’s practically a tautology that, if you disagree with someone on the basis of rationalism and science, you think you are being more rational and scientific than they are.

Because it is an arrogant claim: often made in the sense that Christians are literally anti-science and profoundly irrational. Many studies have established that this is a myth. But it is deeply embedded in the psyche of atheists: especially the anti-theists among you. It’s accepted as a self-evident fact that atheists are the “smart” ones and devotees of science, whereas Christians supposedly are not.

But again, this is often fallaciously based on interaction with those Christians who can’t effectively explain — let alone defend — their opinions. Once we “control” for relative educational level, it is a far different scenario, and this is precisely what I have discovered in my scores and scores of dialogues with atheists. I can only appeal back to those as evidence for my opinions on this score. I can’t undo my own experiences, as if I have never had them.

As I mentioned, I have found that many atheists who rail against the Bible, actually came from an anti-intellectual fundamentalist background (one that I never went through, myself), and ironically, bring those skills of biblical interpretation with them, not realizing that it is a very poor method of biblical exegesis, and by no means the only one or remotely approaching the best method. I see this time and again.

Your reply is not engaging with the essence of my point, which is about a tautology. Please re-read my [first statement] above with that in mind.

I don’t disagree with your tautology. I went much deeper into the question and explained (again) exactly what I meant.

Thanks for the stimulating dialogue!

You are welcome for the dialogue, I know I learned something, I hope you did, too, that’s really the end goal for me. A good dialogue should have both parties who may disagree learn something from the other.

My pleasure as well. Maybe this can be the beginning of some good dialogue in the future. It’s always at a premium these days.

Would you agree that an atheist who disagrees with a Christian in a proper fashion and who tries to apply rational and scientific standards to the disagreement is necessarily drawn to the conclusion that the Christian is not applying those rational and scientific standards properly (and vice versa, for that matter), in other words, not being (properly) rational nor scientific, at least with regards to the issue at hand?

It depends on whether said Christian is acquainted with science and scientific method or not. If not, the atheist would generally be correct in this scenario.

But if the opposite is true, then it is an unfair potshot to imply that the Christian is “against science [and/or] rationality.” The question isn’t whether science or reason are rejected, but rather, it is specific interpretation of same, within a common admiration and respect for those things.

There are few things that irk and infuriate me more as a Christian than to be told I have no respect for reason or science. Only being called a racist or bigot makes me more disgusted. And it’s because the implication is that Christians are intellectual troglodytes and neanderthals.

Some are. It’s the application to the whole group or the majority of a group that makes such charges unconscionable.

I don’t think you are doing this. I think you appear to be a fair-minded and charitable person. But I’m responding to what is often the case.

Would you say that rationality and science are at the foundation, or are essential, to your epistemology as a Christian? If they are, then I totally get that you’d be irked when your commitment to rationality and science are called into question. At that point, disagreement would be over how well one side is using rationality or science.

If they are not, however – if they are supplemental, ancillary to something else that is primary – like faith (when construed as something that does not rely on evidence) – then I think one could fairly be labeled anti-science, etc., at least in regards to the epistemology of whatever it is one has that faith in.

Excellent questions. Most Christians through history (including myself) have believed that reason / science and faith / theology are perfectly harmonious and complementary (therefore part of our overall epistemology). It was pretty much St. Thomas Aquinas’ life-work to make exactly this point. His task was to synthesize Aristotle and Christianity. And he is widely considered the greatest systematic theologian of all time and one of the greatest Christian philosophers.

That’s not to say that the Bible is some sort of scientific or philosophical textbook. The Old Testament is definitely neither (though it is a font of many kinds of wisdom to an extent that most folks, including atheists, have little clue of). The New Testament (especially Paul), on the other hand, shows at least an awareness of philosophy, and to some extent, science (such as it existed then). It is thought that Paul was very well-acquainted with the philosophical ideas and schools of his time (Tarsus was quite the cosmopolitan Greek city). My point is that a thought-out Christianity can be and is harmonious with good philosophy and science, and we need not fear either as “threatening” to our worldview in the least.

There are tiny strains of fundamentalism which are indeed “anti-science” and anti-intellectual, and with little or no concern with philosophy at all. These should never be extrapolated to the whole of Christianity. But it’s done all the time by the anti-theist type of atheists: largely because (here’s my experience again) so many of them were themselves formerly fundamentalists, and so they mistakenly think that adequately represents Christianity, and biblical exegesis. It does not.

As I often say: fundamentalism is a tiny fringe portion of a minority (evangelicalism) of a minority (Protestantism) of Christianity.

I wrote a book about Christianity and science, and I have very extensive web pages on science and philosophy, and atheism.

Thanks again for the excellent, courteous dialogue.

I agree that Christianity could be rational and scientific and yet parts of the Bible need not be a science or logic textbook.

However, I’m not sure you answered my question about the epistemology of Christian theology. Is it founded on rationality and science? Is that where the conclusions of Christian theology about the nature of reality (God exists, etc.) come from, or does it come from another place (internal revelatory experience, or faith [only construed as not relying on evidence])? Or something else?

Perhaps this gets to the heart of one atheist complaint against Christians. Either Christians, in the atheist opinion, are using rationality and science to drive their epistemology and their theology, in which case atheist disagreement would be merely “you’re not doing it right, or well enough,” or Christians base their epistemology and their theology on something besides rationality and/or science, so the atheist disagreement would be “you should be basing your conclusions on rationality and science.”

Which is it?

Theology and faith themselves are neither science nor philosophy. They are different “species.” My point was that they are in harmony with those things (and not necessarily in disharmony), rightly understood.

The question you raise now gets into extremely deep waters. Briefly put, I would say that the Bible and many (if not most) thinking Christians hold that knowledge of God’s existence is innate. Romans 1 states this outright. The Bible assumes that most if not all people know that God exists. Disbelievers, then, are largely categorized as rebels who know God is there and simply reject Him. But (every rule has an exception) there is a lot of room for honest agnosticism or lack of knowledge as well. See my papers:

Are Atheists “Evil”? Multiple Causes of Atheist Disbelief and the Possibility of Salvation

New Testament on God-Rejecters vs. Open-Minded Agnostics

So, getting back to your direct question: Christians believe that faith and reason are harmonious, but there are many different ways that this works out or is applied (different philosophies and/or systems of apologetics). I believe that belief in God is “properly basic,” as philosopher Alvin Plantinga (one of my favorites) likes to put it. It’s simply there, without people thinking about it much (like many other things, such as our assumption that we exist, and that our memories and senses reflect actual external reality).

Now, all the ins and outs of how that works, have been dealt with by minds far greater than mine. So I have collected their articles. See various sections (especially section 2) of this collection: 15 Theistic Arguments (Copious Helpful Resources).

I have read An Essay in Aid of a Grammar of Assent , by Blessed John Henry Cardinal Newman (to be canonized this year). I think this is an excellent treatment of these sorts of “innate” arguments. It’s probably the “heaviest” book I’ve ever read. Dazzling and brilliant, and it is available for free online.

Michael Polanyi is also good on this general topic. I recently summarized my own view of how the theistic “proofs” work:

My Opinion on “Proofs for God’s Existence” Summarized in Two Sentences

My view remains what it has been for many years: nothing strictly / absolutely “proves” God’s existence. But . . .

I think His existence is exponentially more probable and plausible than atheism, based on the cumulative effect of a multitude of good and different types of (rational) theistic arguments, and the utter implausibility, incoherence, irrationality, and unacceptable level of blind faith of alternatives.

I’m reading, right now, Alvin Plantinga’s Warranted Christian Belief (Oxford University Press, 2000). It delves into these “deep” questions for 508 pages. Highly recommended. It does get a bit repetitious and tedious in places, though. I think he could have made his point in 300 pages. :-)

If knowledge that God exists is innate or is properly basic, it would not be scientific, would you agree? Note that it might be true that god exists, yet reaching that conclusion through innate knowledge or it being properly basic would still not make it scientific. Agreed?

I’m not sure how all that would apply if you replace “scientific” with “rational.”

It can be defended philosophically / rationally (this is what Plantinga does in his book, and what many other theistic philosophers have done). It’s not scientific per se, but it is not incompatible with science: especially considering that science begins with unprovable non-empirical axioms (e.g., basic assumptions of uniformitarianism and order and trusting our senses as accurate in terms of observation), and utilizes other necessary non-empirical elements such as logic and mathematics.

In fact, modern science unquestionably took off in a thoroughly Christian society, with Christian starting assumptions. This was no accident or happenstance. And it’s why virtually all the major fields of science were founded by Christians or non-Christian theists.

There are also other scientific-type theistic arguments that figure into the mix: like the cosmological and teleological. I don’t think they prove His existence, but they make it more likely and plausible than not, in my opinion.

So if a properly basic belief is not scientific, and an innate belief is not scientific, then it should be proper for an atheist in a disagreement to characterize them as such in a conversation. You said,

“Atheists generally pride themselves for being the “rational” and “scientific” people and constantly imply that Christians are neither.”

Now, I would agree with your comment above to the extent that if one is not rational in some conversation, that does not justify painting with a broad brush to say that the entire person is wholly not rational. All of us operate rationally sometimes, and not rationally at other times.

But if a Christian justifies their belief on the grounds of innateness or properly-basic-ness, then they must accept the characterization that they are not being scientific. I’m sure the next thing to be said is that everything doesn’t have to be scientific, and that’s another conversation, but at least the characterization by atheists is accurate.

Rational is a whole ‘nother topic that will be more difficult to wade through, at least for me.

It’s the distinction between “this thing x is either scientific in nature or not (i.e., empirical, replicable, etc.)” and “x is anti-scientific, or the holder of x is anti-scientific or frowns upon science simply because he holds (among many other beliefs, including scientific ones) x, which is not technically within the purview of science.”

Minus this distinction, I can say that the atheist is “unscientific” or “against science” or “against empiricism” when he espouses either logic or mathematics: neither of which is empirical or “scientific” and both of which begin with unprovable axioms.

Yes, not everything is scientific (which is self-evident), and as I already stated, science itself must necessarily begin with, and constantly employ axiomatic and non-empirical elements; most notably mathematics and logic. Science itself collapses into philosophy. It is the philosophy of empiricism, which itself is built upon non-empirical elements at its outset.

One easy way to readily see this “dilemma” (i.e., the dilemma for “empirical only” epistemological tunnel vision) is to ponder the claim, “all knowledge is empirical.” This itself is not a species of empiricism or empirical knowledge. It’s a philosophical and epistemological statement dealing with what we can know, and the alleged sweeping parameters of empiricism. How would one test such a statement “in the lab” or empirically? One cannot. It’s an axiom that is unable to be proven, and it is a non-empirical axiom, making a statement about the supposed relation of the philosophy of empiricism with the real world and the sum of all knowledge.

We’ve gotten pretty deep pretty quickly, wouldn’t you say? : )

Yes, very deep! And it will be extra fun for you when I start asking you questions about your beliefs, too!

Forgive me if I try to cut through some really fascinating issues you’ve brought up – it goes against my style to not reply specifically to as many pertinent points an interlocutor mentions – with this:

Is the existence of God an empirical question?

I would say that, ultimately, God’s existence is not an empirical question, if by that one means, “Can God be proven by empirical arguments such as the cosmological and teleological arguments?” I don’t think that absolute proof is possible, as I have already stated.

But those two arguments are still relevant to the discussion; they touch on empirical things, and I think they establish that God’s existence is more likely than not (because they “fit” much better with a theistic world than they do with an atheist world). The Bible itself provides a primitive form of the teleological argument, and connects the universe to God’s existence:

Romans 1:19-20 (RSV) For what can be known about God is plain to them, because God has shown it to them. [20] Ever since the creation of the world his invisible nature, namely, his eternal power and deity, has been clearly perceived in the things that have been made. So they are without excuse;

So does this prove that there is a God by rigid philosophical standards? No. But of course, very few things at all can be proven, if we’re gonna play that skeptical “game.”

But it’s not just something silly and of no consequence. After all, even Einstein (a sort of pantheist) thought that the most sophisticated scientific mind (such as he himself) could look at the universe and feel that there is something behind it, beyond mere materialism. He stated:

My religiosity consists of a humble admiration of the infinitely superior spirit that reveals itself in the little that we can comprehend about the knowable world. That deeply emotional conviction of the presence of a superior reasoning power, which is revealed in the incomprehensible universe, forms my idea of God. (To a banker in Colorado, 1927. Cited in the New York Times obituary, April 19, 1955)

Everyone who is seriously involved in the pursuit of science becomes convinced that a spirit is manifest in the laws of the universe — a spirit vastly superior to that of man . . . In this way the pursuit of science leads to a religious feeling of a special sort . . . (To student Phyllis Right, who asked if scientists pray; January 24, 1936)

In view of such harmony in the cosmos which I, with my limited human mind, am able to recognize, there are yet people who say there is no God. (to German anti-Nazi diplomat and author Hubertus zu Lowenstein around 1941)

Then there are the fanatical atheists . . . They are creatures who can’t hear the music of the spheres. (August 7, 1941)

This is Einstein’s “version” of St. Paul’s statement in Romans 1. And David Hume accepted one form of the teleological argument. He wrote:

The order of the universe proves an omnipotent mind. (Treatise, 633n)

Wherever I see order, I infer from experience that there, there hath been Design and Contrivance . . . the same principle obliges me to infer an infinitely perfect Architect from the Infinite Art and Contrivance which is displayed in the whole fabric of the universe. (Letters, 25-26)

The whole frame of nature bespeaks an intelligent author; and no rational enquirer can, after serious reflection, suspend his belief a moment with regard to the primary principles of genuine Theism and Religion . . .

Were men led into the apprehension of invisible, intelligent power by a contemplation of the works of nature, they could never possibly entertain any conception but of one single being, who bestowed existence and order on this vast machine, and adjusted all its parts, according to one regular plan or connected system . . .

All things of the universe are evidently of a piece. Every thing is adjusted to every thing. One design prevails throughout the whole. And this uniformity leads the mind to acknowledge one author. (Natural History of Religion, 1757, edited by H.E. Root, London: 1956, 21, 26)

Hume seems to have read (and believed!) Romans 1 as well . . .

My tentative position is that it is; if God had no impact or effect within our universe, that god would be indistinguishable from a God that didn’t exist, so empirically the null hypothesis would apply. If God did have an impact with our universe, then we could infer its existence through such impacts as could only come from a God, and maybe begin to infer characteristics from the nature of those impacts, and all that would be an empirical investigation.

Exactly! And that is how science can look into the Big Bang (tying into the cosmological argument) and things like the marvels of molecular biology, along the lines of what biochemist Michael Behe has argued (how did these things ever evolve, from a purely materialistic hypothesis?). In that way, these classic theistic arguments can be analyzed from a scientific point of view, and the hypothesis can be suggested that a God or designer makes more sense of them than sheer materialism.

That is my position. The atheist “explanation” of the existence of the universe is incoherent and implausible, according to what we know from science; the Christian view is plausible and makes perfect sense, even if it is not ironclad proof. Thus, I would say that for one who likes science and interprets the physical world by means of it, theism is the more plausible and believable meta-interpretation or framework.

Note that this is not really the same issue as whether innate or properly basic knowledge is valid, although I’d entertain a proposal to the contrary.

I think perhaps you will respond by saying that it is not an empirical question, but I don’t want to assume that.

As to “basic knowledge”, see my paper: Dialogue with an Agnostic on God as a “Properly Basic Belief”.

***

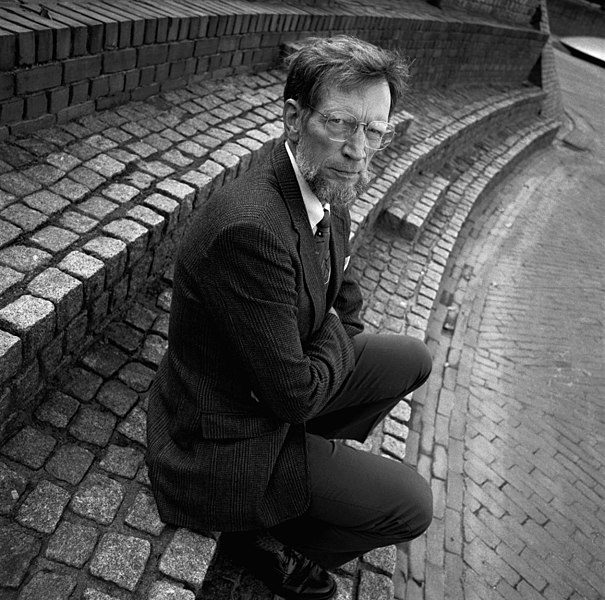

Photo credit: WhiteKnight138 (uploaded on 7-27-17): renowned Christian philosopher Alvin Plantinga [Wikimedia Commons / Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license]

***