Protestant anti-Catholic apologist Jason Engwer has attempted several of these sorts of arguments against the papacy. I have (I think) refuted him many times along these lines, especially after he sought to overthrow some of my own arguments in favor of the papacy:

Dialogue on Development of Doctrine (Esp. the Papacy) [2000]

Dialogue on Doctrinal Development (Papacy & NT Canon) [2-26-02]

*

*

See many many more related articles on my Papacy web page.

Acts 13:1-3 (RSV) Now in the church at Antioch there were prophets and teachers, Barnabas, Simeon who was called Niger, Lucius of Cyre’ne, Man’a-en a member of the court of Herod the tetrarch, and Saul. [2] While they were worshiping the Lord and fasting, the Holy Spirit said, “Set apart for me Barnabas and Saul for the work to which I have called them.” [3] Then after fasting and praying they laid their hands on them and sent them off.

And with this the words of the prophets agree . . .” (15:14-15).

*

After all, it was St. Peter who had already received a revelation from God about all foods being clean (Acts 10:9-16). For some reason God thought it was more important to give him this vision rather than St. Paul. Then in the same chapter, St. Peter’s encounter with the righteous Gentile Cornelius, shows him that non-Jews were to be fully accepted into the Christian community, with the implication that they were not bound to keep the entire Mosaic Law (10:17-43).

Generally speaking, conservative authors have held to the Petrine authorship . . .*The letter plainly indicates that Peter was the author. . . .*Church Tradition [subtitle] Such tradition uniformly ascribes the letter to Peter. There is no other name linked with it in the tradition. . . .*No conclusive reason has been given for denying that the letter is by the author it claims as its writer. None of the objections can be sustained, and it seems better to accept it at face value, as a genuine writing of the apostle Peter.

*

In the very passage that Jason thinks indicates a lack of a papacy, Peter expressly says: “we have the prophetic word made more sure. You will do well to pay attention to this” (1:19). What more does he require? All agree that the Bible must be interpreted by considering it as a whole, and especially all passages on a theme, so as to get the whole picture. This is the Petrine picture. He’s the leader of the Church, and he knows it and acts like it, as my 50 NT Petrine Proofs shows over and over and over.

Another group of relevant contexts is the imagery used to refer to relevant entities, such as what imagery is used to refer to the apostles or the church. We get twelve thrones without Peter’s throne being differentiated (Matthew 19:28), three pillars without Peter’s being differentiated (Galatians 2:9), twelve foundation stones without Peter’s being differentiated (Ephesians 2:20, Revelation 21:14), etc.

This is absolutely classic Jason Engwer pseudo-“argumentation”: which means that it is a classic instance of fallacy and taking things entirely out of context. The essential problem is the typically Protestant “either/or” outlook; whereas the biblical and Hebrew worldview is “both/and.” Not everything has to be mentioned every time. There is more than enough biblical indication of the papacy (see my papers on that; I need not repeat everything), without it having to be noted in every remotely “ecclesiological” context.

The Bible massively teaches that Peter was the leader of the twelve disciples and the early Church. I just showed two passages where Jesus clearly treated him as preeminent. Two more famous ones are Jesus building His Church upon Peter, whom He renamed “the Rock” (Mt 16:18), and His giving Peter (and him only) the “keys to the kingdom” (16:19). The above considerations do not nullify all this. It’s “both/and.” Then there is the aspect of peter being singled out in lists of the disciples and apostles, which I have already dealt with, directly in reply to Jason.

Jesus had just conferred these extraordinary responsibilities and the office of papacy on St. Peter in Matthew 16, but says that twelve disciples will sit on twelve thrones in Matthew 19:28, just three chapters later; and Jason concludes, therefore, that Petr is not a white different from the other twelve. It simply doesn’t follow. Jesus Himself elsewhere refers to “the twelve” (Mk 14:20; Jn 6:70) without singling out Peter; yet in other passages He does precisely that. “Both/and.” In fact, Judas is included in “the twelve”: and sometimes mentioned by name as included in their number (Mt 26:14, 47; Mk 14:10, 43; Lk 22:3, 47; Jn 6:71), including by Jesus Himself (Mk 14:20; Jn 6:70).

Therefore, if Jesus and the Bible can repeatedly refer to “the twelve” [disciples], yet this number can include an evil betrayer, Judas; then by the same token and logic it can include the leader of the twelve, who is often differentiated or singled out in other lists of the disciples (Mk 1:36; Lk 9:28, 32; Acts 2:37; 5:29; 1 Cor 9:5). The same goes for the list of foundation stones. It’s not a “contradiction.” It’s biblical “either/or” thinking.

If Jason wants to press the point of a supposed “egalitarianism” and lack of hierarchy, we can also point to examples of Jesus making Himself “equal” to His own disciples, even though we know He was God and infinitely higher than they were. He calls them “friends” (Jn 15:15) and notes that to be “first” is to be “be last of all and servant of all” (Mk 9:35); He washes their feet (Jn 13:3-16). He submits Himself as a child to Joseph and Mary (“obedient to them”: 2:51). Even in one of Jason’s examples (Eph 2:20), Jesus includes Himself with the disciples as of the foundation stones: “built upon the foundation of the apostles and prophets, Christ Jesus himself being the cornerstone,”. Obviously, He is not lesser than they are; yet He includes Himself.

If He can be described in such terms, and talk in such terms, then all the more so can St. Peter as one of the twelve disciples. It’s much ado about nothing, as always in Jason’s anti-Catholic polemics and sophistry.

St. Paul wrote:

Philippians 4:2-3 I entreat Eu-o’dia and I entreat Syn’tyche to agree in the Lord. [3] And I ask you also, true yokefellow, help these women, for they have labored side by side with me in the gospel together with Clement and the rest of my fellow workers,

Note that Paul commanded Eu-o’dia and Syn’tyche “to agree in the Lord.” So he was higher in authority than them. Yet he calls them (along with Clement) “fellow workers”. Doe this “prove” then, that Eu-o’dia, Syn’tyche, St. Paul, and St. Clement are all “on the same level”: because they are “fellow workers”? No, of course not.

The early Christians often interact with the objections of their opponents. The gospels respond to the charge that Jesus performed miracles by the power of Satan, Paul responds to his critics in his letters, Justin Martyr wrote a response to Jewish arguments against Christianity, Origen wrote a response to Celsus’ anti-Christian treatise, and so on. See here regarding the lack of reference to a papacy in such contexts.

It’s important for Protestants (and other opponents of the papacy) to bring up considerations like these, since the absence of early references to a papacy becomes more significant when the absence occurs across a broader range of contexts. If only two pages of early Christian literature were extant, the absence of a papacy (or whatever other concept) would be much less significant than its absence across two million pages. The number of pages matters (assuming the usual diversity of topics you’d get with an increase in such a page number).

One of the reasons why it’s become so popular for Catholics to argue for the papacy by an appeal to something like typology or Old Testament precedent is that there’s such a lack of evidence in the New Testament and the early patristic literature. So, there’s a turn to other sources to try to find what isn’t present where we’d most expect to see it.

Jason acts as if there is nothing to indicate the papacy in early patristics. But in fact we have a fabulous, clear example of St. Clement of Rome, the fourth pope, who reigned from approximately 88-99 AD. The Corinthian church wrote to him for advice and guidance. It so happens that I wrote about this just about a month ago, and discovered some very striking facts:

Why is it that Clement is speaking with authority from Rome, settling the disputes of other regions? Why don’t the Corinthians solve it themselves, if they have a proclaimed bishop or even if they didn’t claim one at the time? Why do they appeal to the bishop of Rome? These are questions that I think [a Protestant] needs to seriously consider and offer some sort of answer for.

St. Clement writes (I use the standard Schaff translation: no Catholic “bias” there!):

You therefore, who laid the foundation of this sedition, submit yourselves to the presbyters, and receive correction so as to repent, bending the knees of your hearts. Learn to be subject, laying aside the proud and arrogant self-confidence of your tongue. For it is better for you that you should occupy a humble but honourable place in the flock of Christ, than that, being highly exalted, you should be cast out from the hope of His people. (57)

If, however, any shall disobey the words spoken by Him through us, let them know that they will involve themselves in transgression and serious danger; . . . (59, my bolding and italics)

Joy and gladness will you afford us, if you become obedient to the words written by us and through the Holy Spirit root out the lawless wrath of your jealousy according to the intercession which we have made for peace and unity in this letter. (63, my bolding and italics)

Clement definitely asserts his authority over the Corinthian church far away. Again, the question is: “why?” What sense does that make in a Protestant-type ecclesiology where every region is autonomous and there is supposedly no hierarchical authority in the Christian Church? Why must they “obey” the bishop from another region (sections 59, 63)? Not only does Clement assert strong authority; he also claims that Jesus and the Holy Spirit are speaking “through” him.

That is extraordinary, and very similar to what we see in the Jerusalem Council in Acts 15:28 (“For it has seemed good to the Holy Spirit and to us to lay upon you no greater burden than these necessary things”: RSV) and in Scripture itself. It’s not strictly inspiration but it is sure something akin to infallibility (divine protection from error and the pope as a unique mouthpiece of, or representative of God).

The Jerusalem Council was an example of a pope presiding over but acting jointly in concert with bishops and even regular elders (much like ecumenical councils function). But Pope St. Clement was acting unilaterally, which popes can also do. The Jerusalem Council claimed divine guidance and de facto infallibility for the collective group. St. Clement, however, applies it to himself as an individual. If that’s not the papacy in action I don’t know what it would look like. What else could Jason possibly demand as proof? Here we have the papacy in full color and authority even before the first century was over with, and part of the Bible (Revelation) was possibly still being written.

***

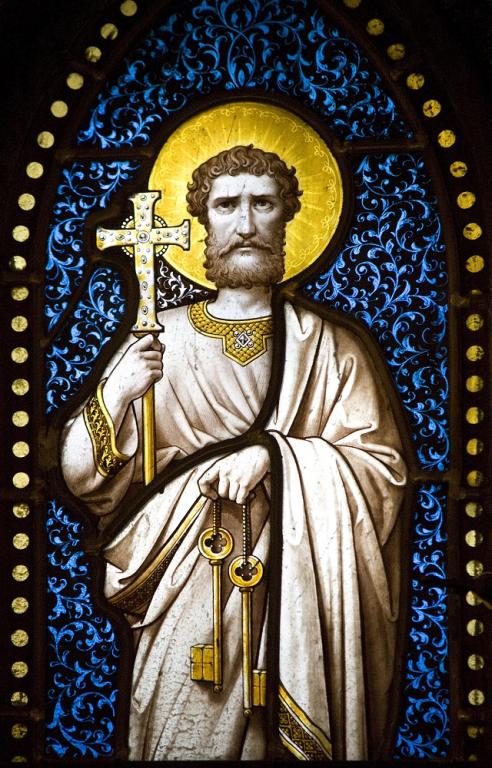

Photo credit: Lawrence OP (8-10-09). 19th-century depiction of St Peter holding the keys of the kingdom of heaven. This window is in the crypt of a chapel of the Upper Basilica in Lourdes [Flickr / CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 license]

***

Summary: Protestant anti-Catholic apologist Jason Engwer attempts to establish the “absence of a papacy” in the NT & in early patristic literature. He’s dead wrong on both counts, as I demonstrate.