Dr. David Nicholls, a vehemently anti-theistic atheist, wrote in his deconversion story (i.e., the tale of his exodus from Christianity):

When I was about 15, I came across a passing reference to the ‘Gospel of Thomas’. I was confused by this and made inquiries that led me to discover the existence of the ‘New Testament apocrypha’. I went to a religious library, run by the Catholic church in Victoria, which had numerous books about the New Testament apocrypha and I still recall reading these books with astonishment. This reading led me to question whether the correct books were in the New Testament canon. Shortly afterwards, I saved up my Saturday job earnings and went to the SPCK in London and bought Edgar Hennecke’s 2-volume New Testament Apocrypha. This introduced me to the very lengthy (and chaotic) process that the church adopted to select the NT canon (a subject never mentioned by the church I attended – most Christians are blissfully unaware of how many gospels, epistles and apocalypses circulated in the first three centuries of the church).*I have seen extravagant claims by Christians who say the canon was settled by the time of Origen (early third century CE), but this is nonsense as it remained undecided as Athanasius’ 39th Festal Letter of 367 CE testifies. Moreover, canonical lists continued to be produced by the church after 367 and these do not always agree with the present canon. The fact that it took the church so long to settle its canon inevitably raises questions, and this is apart from the fact that the post-200 CE church rejected a number of writings used by the early church. Christians can cite 2 Tim 3;16 as much as they like, but it is abundantly clear that the methods used by the church to select its canon were haphazard and erratic.

We shall take a look at this “Gospel of Thomas” and see whether it deserved a place in the New Testament alongside Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. And in so doing, we will expose the shoddiness of Dr. Nicholl’s reasoning (in this respect) for rejecting Christianity.

I. The Nature of Gnosticism / Influence on the “Gospel of Thomas”

Gnosticism took a bewildering variety of forms, but basically it teaches salvation through knowledge (gnosis). Its underlying philosophy is a dualism which regards matter as inherently evil, the product of a demiurge or master-workman who is an inferior being to the Supreme God. The Supreme God, being pure spirit, naturally cannot allow Himself to contract defilement by coming into contact with matter in any way. (Hence Gnosticism cannot accept in their fullness the biblical doctrines of creation, incarnation or resurrection.) . . . In this life men are souls imprisoned in material bodies; it is by true knowledge that they can be liberated from this imprisonment and from the entanglements of the material universe, and thus ascend to the upper world of light where the spiritual nature has its home. Jesus appears in Gnosticism as the redeemer who came to communicate this saving knowledge and effect this liberation; . . .

The document with which we are concerned at present, the Gospel of Thomas, does not bear a Gnostic appearance on its face. Only when we examine it more closely do we see how well adapted it is to the literary company which it keeps. (Bruce [#1 in Bibliography], p. 4)

The Gospel of Thomas presents us with the product of an oral tradition of the sayings of Jesus within a circle whose basic presuppositions differ considerably from those of apostolic Christianity. . . . the original material appears to have been subjected to some Gnosticisation. (Bruce [#1], p. 21)

The upshot of this hermeneutic is that the redactor of the Gospel of Thomas will purposely drop from the tradition anything that makes Jesus’ sayings too clear or univocal, or anything that employs the general saying to highlight one specific (often moral or ecclesial) application. Thus, the redactor naturally undoes what the four canonical evangelists have struggled so hard to do: for, by allegory or other redactional additions and reformulations, the four evangelists often explain the meaning of Jesus’ statements or apply them to concrete issues in the church.

It is these clarifying additions that Thomas systematically drops, thus creating a shorter, tighter version of a saying or a parable. The whole gnostic approach of Thomas makes him favor a laconic, “collapsed,” streamlined form of the tradition. This form may indeed, at times, approximate by coincidence what form critics imagine the primitive tradition to have looked like. . . .

Thomas’ gnostic vision has no room for a multi-stage history of salvation, with its early phase in the OT (replete with prophecies), its midpoint in Jesus’ earthly ministry, death, and resurrection, its continuation in a Church settling down in the world and proclaiming the gospel equally to all men and women, and its climax in a glorious coming of Jesus the Son of Man to close out the old world and create a new one–in other words, so much of what the Four Gospels teach as they related the words and deeds of Jesus. Thomas’ rejection of the material world as evil also means a rejection of salvation history, of a privileged place in that history for Israel, of the significance of OT prophecies, of any real importance given to the “enfleshed” earthly ministry of Jesus leading to his saving death and bodily resurrection, of a universal mission of the Church to all people (instead of only to a spiritual elite), and of a future coming of Jesus to inaugurate a new heaven and a new earth.

In other words, Thomas’ view of salvation is ahistorical, atemporal, amaterial, and so he regularly removes from the Four Gospels anything that contradicts his view. Severin, for instance, demonstrates convincingly how Thomas pulls together three diverse parables in sayings 63, 64, and 65 (the parables of the rich man who dies suddenly, of the great supper, and of the murderous tenants of the vineyard) to develop his own gnostic polemic against “capitalism,” while rigorously censoring out of the parables any allegory, any reference to salvation history, and any eschatological perspective. The result is a dehistoricized, timeless message of self-salvation through self-knowledge and ascetic detachment from this material world. At times, Thomas will introduce amplification into the tradition, but they always serve his theological program. (John P. Meier, A Marginal Jew–Rethinking the Historical Jesus, Doubleday: 1991, Vol. 1, 133-134)

II. The Gospel is Not “Secret Knowledge”

The Gospel of Thomas begins as follows:

These are the secret words which the living Jesus spoke and Didymus Judas Thomas wrote. And he said: Whosoever finds the explanation of these words shall not taste death. . . .

The secret approach found in the Gospel of Thomas is typical of the writings of the Gnostics; those who supposedly had “secret” knowledge. . . . in contrast to the Gospel of Thomas, the four Gospels are open about the ways of salvation and the kingdom of God. Indeed, Jesus talked about proclaiming the truth openly to everyone. We read the following words of our Lord in Matthew:

“What I tell you in the dark, speak in the daylight; what is whispered in your ear, proclaim from the roofs.” (Matthew 10:27 NIV) . . .

In front of the former High Priest, Annas, Jesus made it clear that His was an open message to the world. He said,

Jesus answered him, “I spoke openly to the world. I always taught in synagogues and in the temple, where the Jews always meet, and in secret I have said nothing.” (John 18:20 NKJV) (Stewart: #3)

III. The “Gospel of Thomas” is Not Apostolic (i.e., It is of Late Origin)

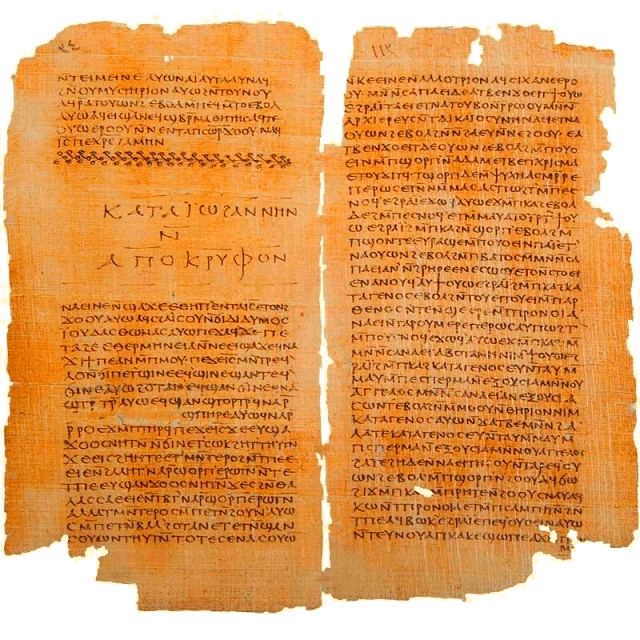

In 1945, or perhaps a year or two earlier, some peasants in Upper Egypt accidentally dug into an early Christian tomb. In it they found a large jar containing thirteen leather-bound papyrus codices. These codices proved to contain forty-eight or forty-nine separate works, mostly Coptic translations from Greek. . . . [I]t is one of these codices that contains the Gospel of Thomas. (Bruce [#1], p. 3)

The author of [the Gospel of Thomas] shows a decided dependence on the canonical Gospels (see below for the evidence), demonstrating a later date for its composition than they. (Miller: #4)

The only firm evidence for dating this document is its earliest Greek fragments (P. Oxy. 1), which was written no later than about A.D. 200. . . . The first reference to the document by name occurs no earlier than Hippolytus, who was writing between A.D. 222 and 235.(Witherington: #5, p. 49)

Richard Hayes, a non-evangelical teaching at Duke, wrote an article demonstrating how the Jesus Seminar did NOT represent a cross-section or consensus view of non-evangelical scholarship in “The Corrected Jesus”, First Things 43 (1994). He called the seminar’s dating of [the Gospel of Thomas] “an extraordinarily early dating, ” a highly controversial claim,” and a “shaky element in their methodological foundation.” (Miller, #4; Hayes cited by Bock, in Wilkins and Moreland [#6], p. 90)

[T]he document may have first been written as early as about A.D. 150, but no actual evidence permits us to push that date a century earlier as the Jesus Seminar does. (Craig Blomberg, in Wilkins and Moreland [#6], p. 23)

It should be mentioned that an important, specialist work on the Syrian area, where [the Gospel of Thomas] was possibly written, argues that [the Gospel of Thomas] is dependent on Tatian’s Diatessaron, which would dates it after 180 AD–see H.J.W. Drijvers, in “Facts and Problems in Early Syriac-Speaking Christianity”, The Second Century, 2 (1982), pp. 157-175. (Miller, #4)

Bart Ehrman argues the Gospel of Thomas is a 2nd Century Gnostic text based on the lack of any reference to the coming Kingdom of God and return of Jesus. The earliest leaders of the Church also recognized the Gospel of Thomas was a late, inauthentic, heretical work. Hipploytus identified it as a fake and a heresy in “Refutation of All Heresies” (222-235AD), Origen referred to it in a similar way in a homily (written around 233AD), Eusebius resoundingly rejected it as an absurd, impious and heretical “fiction” in the third book of his “Church History” (written prior to 326AD), Cyril advised his followers to avoid the text as heretical in his “Catechesis” (347-348AD), and Pope Gelasius included the Gospel of Thomas in his list of heretical books in the 5th century. (J. Warner Wallace, #7)

Bart D. Ehrman argues that the historical Jesus was an apocalyptic preacher, and that his apocalyptic beliefs are recorded in the earliest Christian documents: Mark and the authentic Pauline epistles. The earliest Christians believed Jesus would soon return, and their beliefs are echoed in the earliest Christian writings. The Gospel of Thomas proclaims that the Kingdom of God is already present for those who understand the secret message of Jesus (Saying 113), and lacks apocalyptic themes. Because of this, Ehrman argues, the Gospel of Thomas was probably composed by a Gnostic some time in the early 2nd century.[64] Ehrman also argued against the authenticity of the sayings the Gospel of Thomas attributes to Jesus.[65] (Wikipedia [#8] )

For further discussion of why the “Gospel of Thomas” was never considered by the early Church to be canonical, see “Why the Gospel of Thomas Isn’t in the Bible”, by Ryan Leasure, Cross Examined, 9-7-19. For the canonical process in general, see my articles:

The New Testament Canon & Historical Processes [1996]

Church Authority & the Canon (vs. Calvin #59) [2012]

The New Testament Canon is a “Late” Doctrine [National Catholic Register, 1-22-18]

IV. “Another Jesus”

[N]ot only the passion narrative, but even sayings of Jesus relating to His passion, are conspicuously absent from the Gospel of Thomas. (Bruce [#1], p. 21)

When we come to the most important question of all―the testimony which this document bears to Jesus―we feel that we are no longer in touch, even remotely, with the evidence of eyewitnesses. The Jesus of the Gospel of Thomas is not the Jesus who came to serve others, not the Jesus who taught the law of love to one’s neighbour in the way portrayed in the parable of the good Samaritan. The religion of the Gospel of Thomas, as of Gnosticism in general, is an affair of the individual. Unlike the Bible, the Gospel of Thomas sets forth the ideal of the ‘solitary’ believer. When the Jesus of the Gospel of Thomas speaks of His mission in the world, this is what he says (Saying 28):

I stood in the midst of the world and I manifested myself in the flesh to these. I found them all intoxicated; I found none thirsty among them. And my soul was grieved for the children of men, because they are blind in heart and do not see; because they have come into the world empty, they still seek to go out of the world empty. But may someone come and set them right! Then, when they have slept themselves sober, they will repent.

No doubt there is a real concern for the blindness and ignorance of men expressed in these words, but on the whole it is the concern of one who has come to show them the true way rather than of one who has come to lay down his own life that true life may be theirs. What the Jesus of the Gospel of Thomas has come to give is secret knowledge, . . . (Bruce [#1], pp. 21-22)

Far from containing a passion narrative, the Gospel of Thomas has not even any room for those sayings of Jesus which make reference to his death. The good news which its compiler really wishes to commend is good news for the “solitary” member of a spiritual elite, assuring him that by the path of true knowledge he may escape from the fetters of his bodily existence and other material encumbrances and so ascend to the upper realm of light, the true home of his spirit. (Bruce [#2], p. 324)

The Gospel of Thomas is very different in tone and structure from other New Testament apocrypha and the four Canonical Gospels. Unlike the canonical Gospels, it is not a narrative account of the life of Jesus; instead, it consists of logia (sayings) attributed to Jesus, . . . The text . . . does not mention his crucifixion, his resurrection, or the final judgement; nor does it mention a messianic understanding of Jesus. (Wikipedia [#8])

N.T. Wright, Anglican bishop and professor of New Testament history, also sees the dating of Thomas in the 2nd or 3rd century. Wright’s reasoning for this dating is that the “narrative framework” of 1st-century Judaism and the New Testament is radically different from the worldview expressed in the sayings collected in the Gospel of Thomas. Thomas makes an anachronistic mistake by turning Jesus the Jewish prophet into a Hellenistic/Cynic philosopher. Wright concludes his section on the Gospel of Thomas in his book The New Testament and the People of God in this way:

[Thomas’] implicit story has to do with a figure who imparts a secret, hidden wisdom to those close to him, so that they can perceive a new truth and be saved by it. ‘The Thomas Christians are told the truth about their divine origins, and given the secret passwords that will prove effective in the return journey to their heavenly home.’ This is, obviously, the non-historical story of Gnosticism … It is simply the case that, on good historical grounds, it is far more likely that the book represents a radical translation, and indeed subversion, of first-century Christianity into a quite different sort of religion, than that it represents the original of which the longer gospels are distortions … Thomas reflects a symbolic universe, and a worldview, which are radically different from those of the early Judaism and Christianity. (Wikipedia [#8], citing Wright [#9], p. 443)

V. Anti-Marriage / Anti-Procreation / Anti-Female

(No. 79):

In the crowd a woman said to him: ‘Happy the womb that gave you birth and the breasts that suckled you!’ He said to her: ‘Happy are those who have heard the Father’s word and keep it. Verily, the days will come when you will say: “Happy the womb that never gave birth and the breasts that never suckled children!” ’

. . . [This] suggest[s] that the bearing of children is contrary to the Father’s will, and that those who renounce marriage and family life are to be congratulated. This, of course, completely dehistoricises the second part of the saying, where Jesus in Luke xxiii. 29 is not laying down a permanent principle, but telling the weeping women on the Via Dolorosa that, when the impending distress overtakes Jerusalem, childless women will have something to be thankful for. (Bruce [#1], p. 14)

A modern reader will find the references to women and to marriage out of keeping with the general tenor of the canonical Gospels. Sexual life and the propagation of children are discouraged, as we have seen in Saying 79 (p. 14 above). The ideal state is to be as free from sexual self-consciousness as little children are.’ There are several sayings to this effect which are obviously related to words ascribed to Jesus in the Gospel according to the Egyptians, another work of Naassene affinities. In the Gospel according to the Egyptians this attitude is summed up in the statement: ‘I came to destroy the works of the female.’ This statement is not reproduced in the Gospel of Thomas, but others from the same source and to the same effect are found. Thus Saying 22 contains the words:

Jesus said to them: ‘When you make the two one … and when you make the male and the female one, so that the male is no longer male and the female no longer female…. then you will enter the kingdom.’ . . .

Women, one gathers, cannot attain to the higher life. This is the implication of Saying 114:

Simon Peter said to them: ‘Let Mary depart from our midst, because women are not worthy of the life [that is life indeed].’ Jesus said: ‘See, I will so clothe her that I may make her a man, in order that she also may become a living spirit like you men. For every woman who becomes a man will enter into the kingdom of heaven.’

In spite of her faithfulness as a disciple, even Mary Magdalene can enter the kingdom only by being changed into a man (perhaps in a future phase of existence). We may infer that women, because of their function in conception and childbirth, were judged incapable of ever achieving complete liberation from material entanglements. (Bruce [#1], pp. 18-19)

Bibliography

1) F.F. Bruce, “The Gospel of Thomas,” Faith and Thought 92.1 (1961): 3-23

2) F.F. Bruce, “When is a Gospel Not a Gospel?” Bulletin of the John Rylands Library 45.2 (March 1963): 319-339.

3) Don Stewart, “What is the Gospel of Thomas?” (Blue Letter Bible).

4) Glenn Miller, “What about the Gospel of Thomas?”, Christian Think Tank (24 August 1996).

5) Ben Witherington III, The Jesus Quest: The Third Search for the Jew of Nazareth, Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press: 1995.

6) Michael J. Wilkins & J. P. Moreland, editors, Jesus Under Fire–Modern Scholarship Reinvents the Historical Jesus, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan Academic, 1996.

7) J. Warner Wallace, “Why Shouldn’t We Trust The Non-Canonical Gospels Attributed To Thomas?” (Cold-Case Christianity, 4-18-18)

8) Wikipedia, “Gospel of Thomas”.

9) N.T. Wright, The New Testament and the People of God, Fortress Press, 1992.

***

Photo credit: Gospel of Thomas and The Secret Book of John (Apocryphon of John), Codex II The Nag Hammadi manuscripts. Early Christian Gnostic texts [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

***

Summary: I provide various reasons for why the “Gospel of Thomas” is not an authentic Gospel, & not fit for inclusion in the NT canon. It invents “another Jesus” (2 Cor 11:4).